'Tis the season to sit on the sofa and binge Christmas films, and what better place to start than Love Actually? It feels beginner friendly – Christmassy enough to get excited, but not so Christmassy that you’re immediately thrust into that Twixmas catatonia feeling, when nothing else feels appropriate to watch but you’ve seen enough red and green décor to last a lifetime, so you simply sit and accept your fate, mainlining Cadbury’s Heroes and second screening TikTok ‘What I got for Christmas’ videos from out of touch influencers.

Speaking of social media trends, Love Actually is similarly high on everyone’s Christmas watch lists right now – but not necessarily out of ‘love’. That’s right, the annual ‘Is Love Actually actually awful?’ discourse has restarted, with many confessing that they hate watch it most years just to recount how problematic it is.

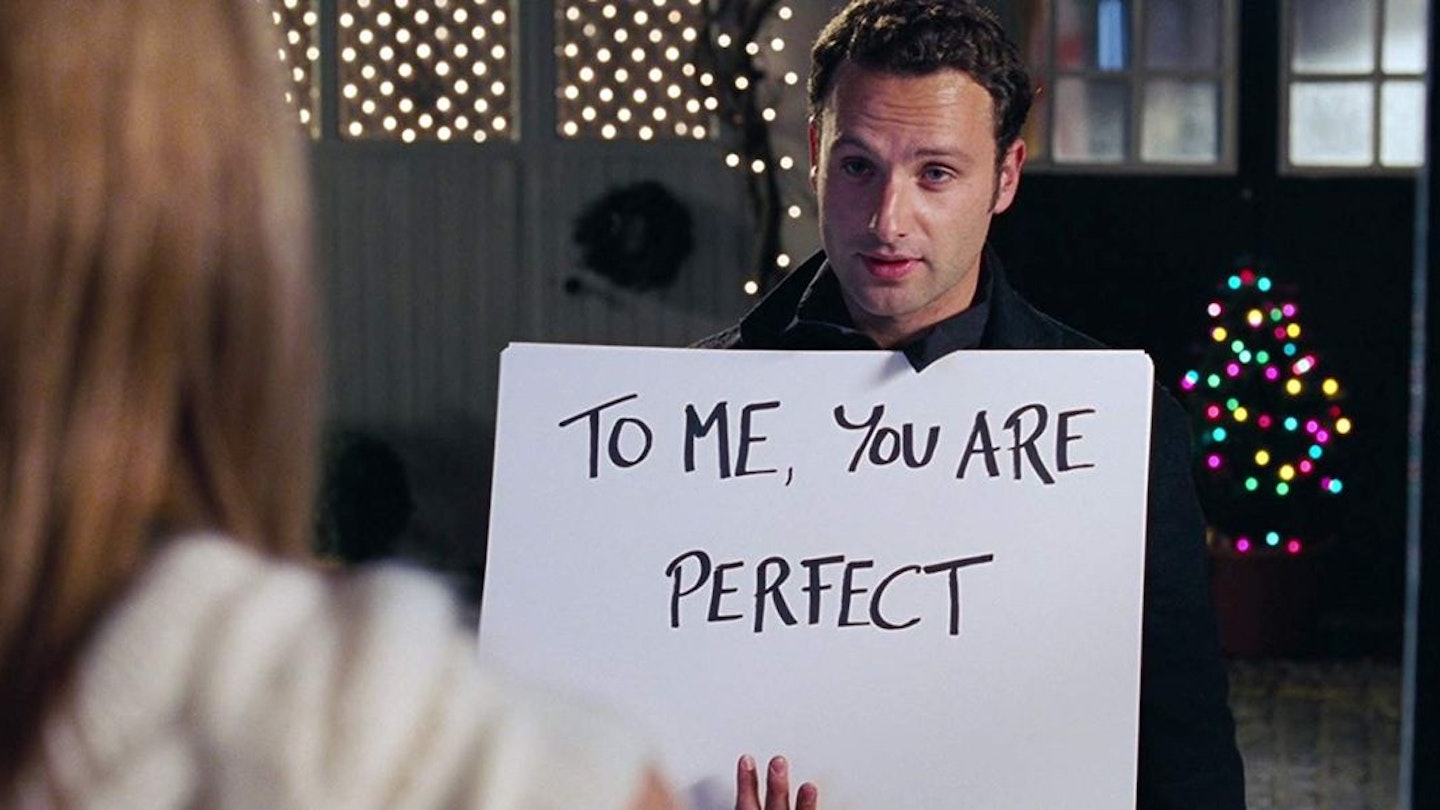

Most recently, Keira Knightley - who plays the Juliet in the film (now the subject of many an online meme) - called a scene at the end of the movie 'creepy.' The scene in question is a culmination of Marks strange obsession with Juliet, his best friend's wife who he’s never had a real conversation with (not to mention the fact Knightley was just 18 when she starred in Love Actually). It sees Mark come to Juliet's door to admit his feelings for her by reading a series of cue cards, while a Boombox plays Silent Night. Admittedly, it hasn't aged well.

This week, Knightley told the Los Angeles Times she voiced this to director Richard Curtis on set. 'The slightly stalkerish aspect of it – I do remember that,' Knightley reflected. 'My memory is of Richard, who is now a very dear friend, of me doing the scene, and him going, "No, you’re looking at [Lincoln] like he’s creepy," and I’m like, "But it is quite creepy."' She added: 'And then having to redo it to fix my face to make him seem not creepy.'

Knightley was then asked if she sensed a 'creep factor' about the scene while shooting, to which she replied: 'I mean, there was a creep factor at the time, right? Also, I knew I was 17. It only seems like a few years ago that everybody else realised I was 17.'

Andrew Lincoln, who plays Peter, remembered having similar concerns in an interview with Vanity Fair in 2017. 'I kept saying to Richard, ‘Are you sure I’m not going to come off as a creepy stalker?’ he said.

This isn't the first time Love Actually has been called out in recent years as not exactly standing the test of time when it comes to appropriateness. Made in 2003, a number of the storylines are uncomfortable for viewers in 2024. There’s the strange marriage proposal between Jamie and Aurelia who also have never shared one single conversation given they do not speak the same language. Then there’s the fact Natalie, played by Martine McCutcheon, is continuouslybody-shamed throughout the film – which undoubtedly impacted women’s ideas of body image in the already toxically thin noughties era.

Even director Richard Curtis has acknowledged that the film is ‘out of date’ now, admitting in a Love Actually special in 2022 that he’s uncomfortable with some of the plot points, as well as how white and heteronormative the film is.

The lack of diversity makes me feel uncomfortable and a bit stupid.

Richard curits

'The lack of diversity makes me feel uncomfortable and a bit stupid,’ Curtis said. ‘'There is sort of these plots that have bosses and people who work for them. I think the 20 years show what a youthful optimist I probably was when I wrote it.’ More recently, during an appearance at The Times and Sunday Times Cheltenham Literature Festival, Scarlett Curtis, feminist author, and Richard’s daughter, questioned him on the use of fat jokes and how women of colour are framed in his films.

‘As your daughter, I can confirm that you're a wonderful man, and I like to think I've taught you a lot about feminism. So, this is by no means the moment I cancel my dad live on stage. But in the last few years, there has been growing criticism from a lot of people about the ways your film, in particular, treated women of colour,’ Scarlett said. ‘Just to name a few of my faves: 'tree trunk thighs'; Bridget [Jones] being overweight when she's just a very skinny white woman; multiple counts of inappropriate male behaviour in Love Actually including the actual prime minister; a general feeling that women are visions of unattainable loveliness; and the noticeable lack of people of colour in a film called Notting Hill, which was quite literally one of the birthplaces of the British black civil rights movement.’

When asked if he has any regrets about his filmmaking, Richard responded ‘I remember how shocked I was five years ago when Scarlett told me, “You can never use the word 'fat' again.” Wow, you were right. In my generation, calling someone chubby [was funny] — in Love Actually there were jokes about that…Those jokes aren't any longer funny. I don't feel I was malicious at the time, but I feel I was unobservant and not as clever as I should have been.’

‘I wish I'd been ahead of the curve,’ he continued. ‘Because I came from a very undiverse school and a bunch of university friends, I think that I've hung on to the diversity issue to the feeling that I wouldn't know how to write those parts. I think I was just sort of stupid and wrong about that.’

So, if even Richard Curtis himself can note that Love Actually is problematic, we can all agree that the film generally hasn’t aged well. But and I ask this with caution, does that mean we can’t enjoy it at all? Not even the great ensemble cast and their acting? Not even the early 00s nostalgia (the feel-good parts, not the fat shaming of course)? Not even the glimpses of sweet, authentic love stories that actually are endearing to watch?

With the problematic nature of the film firmly decided upon, conversations have turned from whether the film is appropriate to whether it’s even good at all, entertainment wise. And thus, we have another area of intense division in England – the annual Love Actually hate watchers, and the staunch Richard Curtis defenders. It appears that whether you love or loathe the film says a lot about you as a person.

So, where do you sit on the Love Actually divide?