New York, December, 2018: Daniel Roseberry would wake up on the floor of a friend’s SoHo apartment where he was crashing and head off to a cold, dusty studio in Chinatown. There, as the Manhattan Bridge above the building shuddered with trains, he would spend the day sketching, compiling a project for a role he was in the running for. He had left a job he loved, as design director at Thom Browne, terrifying, he admits, ‘but I knew I needed to create a void in my life in order for something to come fill it.'

It did. Fast-forward to Paris, July 2019 and these sketches had sprung to life as Roseberry’s first collection for Schiaparelli – and the new artistic director’s first ever couture offering. In under two years, he’s not just made his mark, but established himself as one of fashion’s most exciting talents. Even a global pandemic can’t halt his momentum; the most recent awards season saw Schiaparelli a hit among A-listers who prioritise looking interesting rather than predictably pretty: see Bella Hadid in a black gown complete with gilded brass necklace in the shape of trompe l'oeil lungs from the AW21 couture collection recently shown in Paris.

Emma Corrin also wore a mini dress festooned with gigantic, glinting teeth, there was Beyoncé in a leather LBD and gloves with trompe l’oeil fingernails and, for the Christmas holidays last year, Kim Kardashian West chose a Hulk-ish, fully-abbed green bodice.

How did it feel the first time he, then largely unknown, walked into the Schiaparelli headquarters on the Place Vendôme, the first American to head up a French couture house? ‘It’s so fitting it was at Schiaparelli because there really is no word other than “surreal”,’ he says on a Zoom call from Paris, where thanks to lockdown he has lived a largely ‘monastic’ life since arriving. Indeed. Surrealism was integral to Elsa Schiaparelli’s work. Her lobster hat, skeleton dress and signature colour – shocking pink – remain iconic today, as do her collaborations with artists like Salvador Dalí.

Taking on a house with such illustrious heritage comes with a hefty helping of pressure. ‘I knew going into it that most relaunches of houses do not work. A big question for me was “why?”,’ says Roseberry, adding that impersonations ‘feel disingenuous and fall flat’. So, artist collaborations were out and, although he spent a day at the Met looking at archival pieces, none was referenced in his first few collections. ‘I wasn’t like “let’s burn it down” but I really didn’t want it to feel nostalgic at all,’ he says. ‘The primary focus was let’s 180 the house, make the conversation completely different and just make a scene.’

While the clothes do make a scene, Roseberry – composed, thoughtful, affable – is the antithesis of the theatrical showman. Raised in Dallas, the son of a minister, his earliest memories of clothes are of his mother getting ready for church (‘it’s kind of drag-ish; I love the performative, ceremonial aspect’). He admired the ‘intersection between the way my mom dressed and her graciousness to other people. I’ve never been inspired by bitchy people who look good. It’s much more interesting and much more modern to be someone who looks incredible but is also full of grace for the people around you.’

As a teenager, Roseberry would pour over Vogue, marvelling at John Galliano’s Dior, Karl Lagerfeld’s Chanel. ‘But it never felt like something I could even dream to be a part of. When I started here that was one of the first things I said: I really want to open the doors up of the house, to our process, to my process, to seeing the way that clothes are made so that people might feel more invited to be a part of [it] with us.’ He wants young people to give themselves permission to participate. It was fashion, he says, that inspired him to move out of his hometown. Its impact can be formative.

It’s odd that the relevancy of couture is so often questioned in a way other arts aren’t. It’s the ostentation, the extravagance, the princessy gowns that can distract from the intimacy and artistry of the craft. Rather than be shackled by the rigour of the craft and heritage, Daniel has been emboldened, liberated even, by it. ‘[We can be] perverse and joyful in an interesting way, and not precious about things. These clothes are made on the fifth floor in the Place Vendôme, we have nothing to prove to anybody. They are so elevated but then we get to redefine what elevated looks like.’

There’s something irresistibly punky about this attitude. ‘It’s that weird thing because it is one of the grand couture houses but it’s also a lot about questioning the rules.’

He doesn’t shy away from wit, absurdity, even the ugly. It’s a pertinent message for now, a reminder that people can be both silly and cerebral, sexy and serious, glamorous and provocative. ‘I like the dichotomy of a personality,’ he says. ‘I love that there’s a performer inside us and then I love that there’s an introvert inside us.’

It’s this duality, coupled with the ‘why not?’ attitude spurred on by pandemic – life is short, just take the damn risk, have fun with it – that emboldens his fans to try something different. ‘When people choose things that are that strong and look that good it’s so encouraging,’ says Roseberry. ‘All I want to do is serve and amplify that moment.’

Perhaps Roseberry’s biggest moment to date, however, has been the sweeping red silk faille skirt and navy cashmere jacket – embellished with a gilded dove of peace brooch – that Lady Gaga wore to the presidential inauguration. He still gets chills thinking about it. ‘The fact that we got to be a part of that in such a beautiful way will always be shocking to me.’

The inauguration was charged with hope, and there is a sense that globally we’re on the cusp of something new. It’s time to shake up the system. With fashion in introspection mode, there is space there too for change, curiosity. This fever-dream year, sartorially defined forever by trackpants, however, has left us all questioning the purpose, relevance of fashion, asking whether clothes matter.

‘Do clothes ultimately matter? I don’t think so. I don’t think in the grand scheme of things what you put on your back is ultimately what you’re going to remember before you die,’ Roseberry says.

‘But dreams matter, beauty matters and vulnerability matters and confidence and humour, those abstract ideas that can be channelled and captured in moments and visual elements, like clothes or in any of the arts. I’m not obsessed with making gowns for the rest of my life. I love that Schiaparelli is about ideas first. She really just asked people to think about fashion in a broader sense and if I even get to 1% of that mark I'm thrilled.'

SEE: The Best Dressed Celebrities At Cannes Film Festival 2021

1 of 73

1 of 73Maggie Gyllenhaal in Gucci

2 of 73

2 of 73Rosamund Pike in Dior

3 of 73

3 of 73Tilda Swinton in Loewe

4 of 73

4 of 73Gessica Geneus

5 of 73

5 of 73Fatou N'Diaye

6 of 73

6 of 73Sharon Stone in Dolce & Gabbana

7 of 73

7 of 73Tilda Swinton wearing Schiaparelli

8 of 73

8 of 73Lucie Zhang in Lanvin

9 of 73

9 of 73Melanie Laurent

10 of 73

10 of 73Tilda Swinton

11 of 73

11 of 73Isabelle Huppert

12 of 73

12 of 73Noel Capri Berry

13 of 73

13 of 73Maria Bakalova wearing Louis Vuitton

14 of 73

14 of 73Amina Muaddi wearing Louis Vuitton

15 of 73

15 of 73Lous and the Yakuza wearing Louis Vuitton

16 of 73

16 of 73Isabeli Fontana

17 of 73

17 of 73Tilda Swinton

18 of 73

18 of 73Mati Diop

19 of 73

19 of 73Tilda Swinton wearing Haider Ackermann

20 of 73

20 of 73Maggie Gyllenhaal in Chanel

21 of 73

21 of 73Melissa George wearing Giorgio Armani Prive

22 of 73

22 of 73Timothee Chalamet in Tom Ford

23 of 73

23 of 73Anna Cleveland in Alberta Ferretti

24 of 73

24 of 73Jodie Turner-Smith

25 of 73

25 of 73Salma Hayek

26 of 73

26 of 73Vanessa Paradis

27 of 73

27 of 73Carla Bruni-Sarkozy

28 of 73

28 of 73Bella Hadid wearing Schiaparelli

29 of 73

29 of 73Marion Cotillard

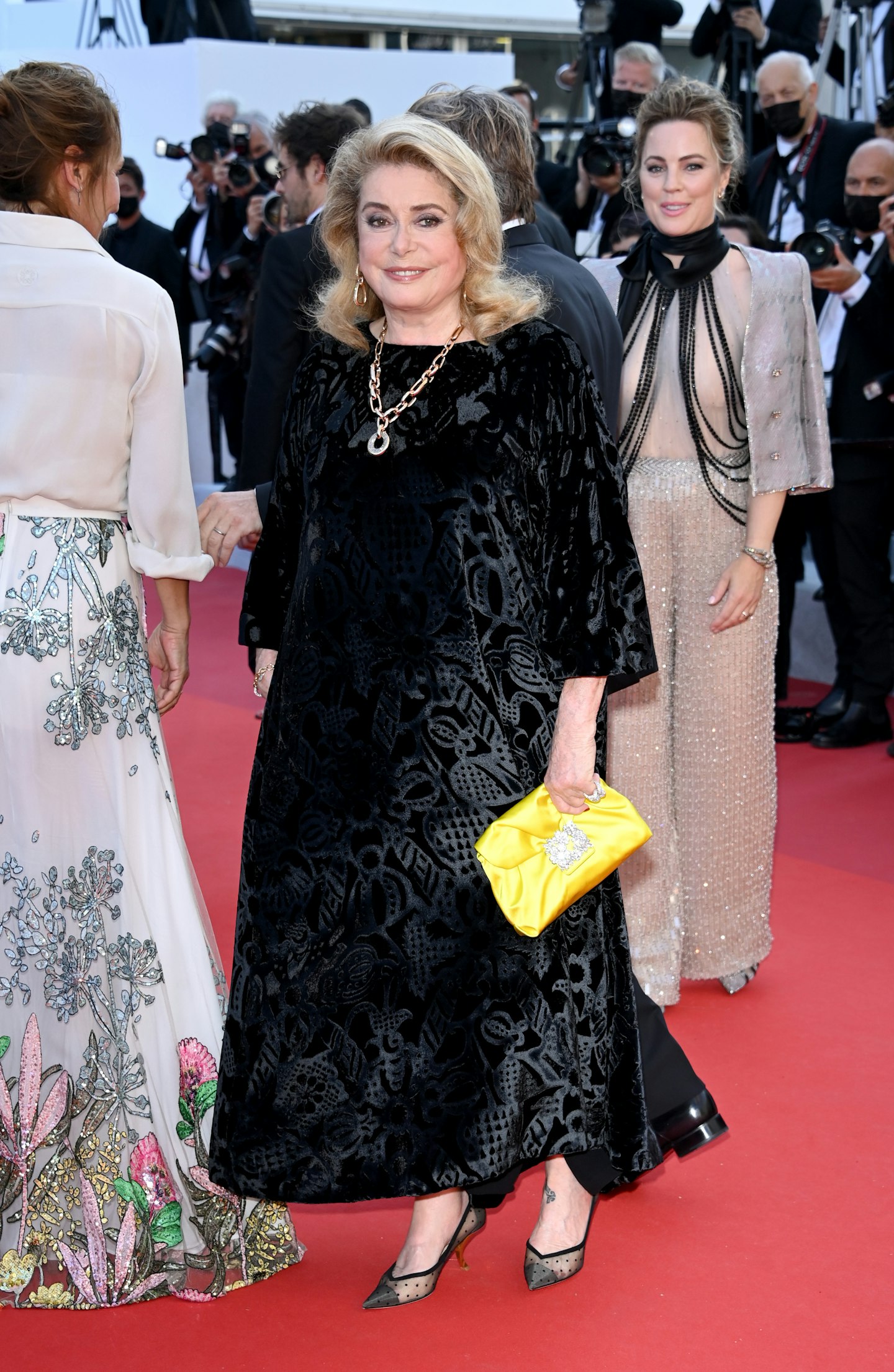

30 of 73

30 of 73Catherine Deneuve

31 of 73

31 of 73Bella Hadid wearing Dior

32 of 73

32 of 73Tina Kunakey wearing Valentino Haute Couture

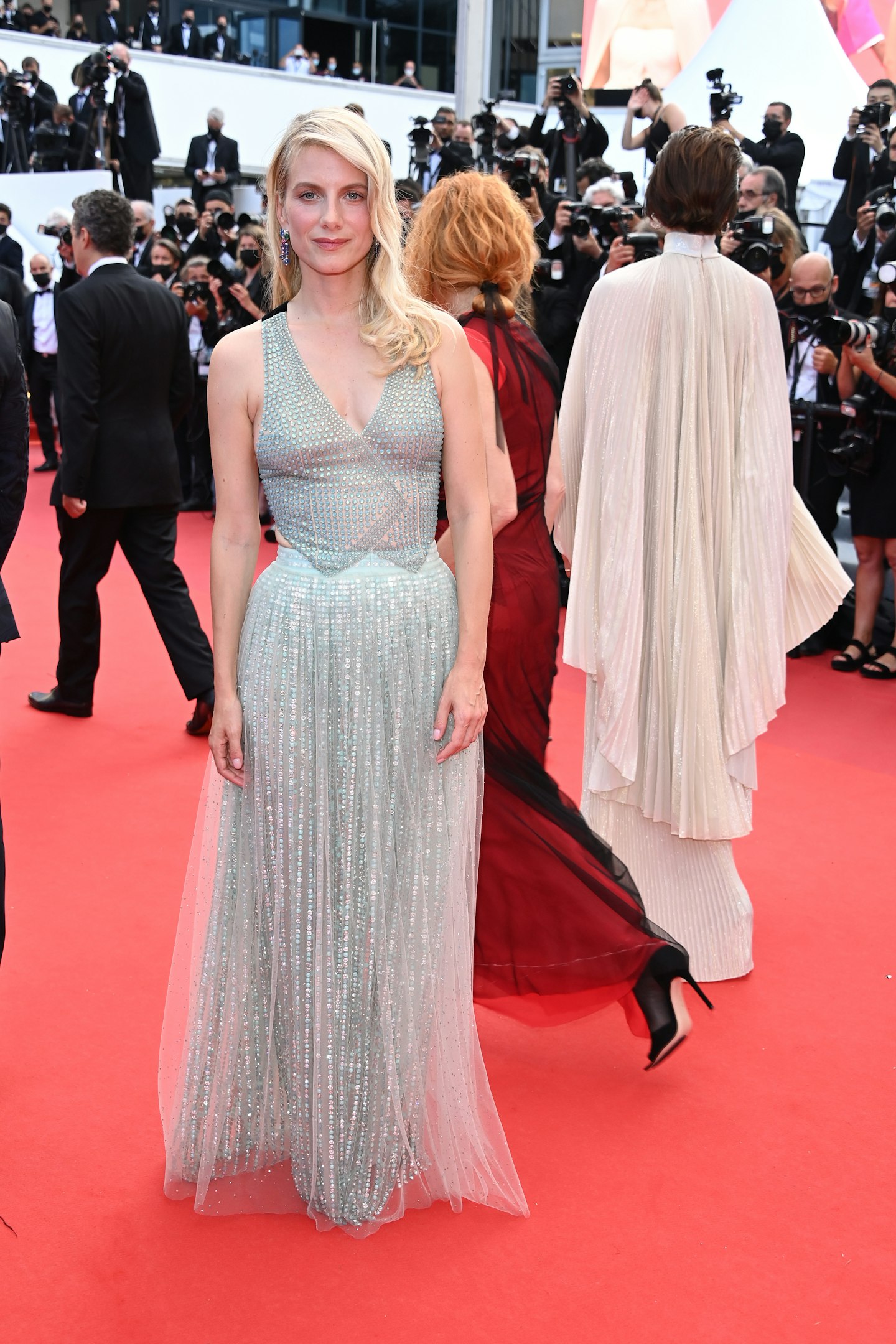

33 of 73

33 of 73Melanie Laurent

34 of 73

34 of 73Aïssa Maïga

35 of 73

35 of 73Jessica Chastain

36 of 73

36 of 73Soo Joo Park wearing Mugler

37 of 73

37 of 73Maggie Gyllenhaal wearing Versace

38 of 73

38 of 73Dylan Penn wearing Giorgio Armani Prive

39 of 73

39 of 73Camille Cottin

40 of 73

40 of 73Jodie Turner-Smith in Gucci

41 of 73

41 of 73Helen Mirren

42 of 73

42 of 73Soo Joo Park wearing Chanel

43 of 73

43 of 73Charlotte Gainsbourg

44 of 73

44 of 73Jane Birkin

45 of 73

45 of 73Tilda Swinton

46 of 73

46 of 73Camille Cottin

47 of 73

47 of 73Abigail Breslin

48 of 73

48 of 73Deborah Lukumuena

49 of 73

49 of 73Bella Hadid in Lanvin

50 of 73

50 of 73Jodie Foster in an embellished Givenchy gown with Chopard jewels

51 of 73

51 of 73Marion Cotillard in a one-shoulder, silver metallic Chanel dress with peplum waist

52 of 73

52 of 73Marion Cotillard wore a full Chanel look for a photocall, consisting of cycling shorts and a printed blouse

53 of 73

53 of 73Bella Hadid in a Jean Paul Gaultier dress from the designer's spring/summer 2002 collection

54 of 73

54 of 73Helen Mirren in a Dolce and Gabbana dress

55 of 73

55 of 73Andie MacDowell in a grey embellished Prada dress

56 of 73

56 of 73Maggie Gyllenhaal wore a pleated bustier couture gown and cape from Celine by Hedi Slimane

57 of 73

57 of 73Candice Swanepoel in a rose gold jumpsuit by Etro

58 of 73

58 of 73Carla Bruni wore Celine by Hedi Slimane

59 of 73

59 of 73Jessica Chastain wore a Dior Haute Couture strapless gown with Chopard jewels

60 of 73

60 of 73Kat Graham wore a green Etro gown with Pomellato jewels

61 of 73

61 of 73MJ Rodriguez wore a hooded Etro gown

62 of 73

62 of 73Spike Lee in a fuchsia Louis Vuitton suit

63 of 73

63 of 73Melanie Laurent in an Armani Privé gown

64 of 73

64 of 73Soko in Gucci

65 of 73

65 of 73Mati Diop in a lace Chanel dress

66 of 73

66 of 73Chiara Ferragni in a Celine crop top with wide leg, ripped jeans

67 of 73

67 of 73Izabel Goulart in David Koma

68 of 73

68 of 73Diane Kruger in Armani Prive

69 of 73

69 of 73Eva Herzigova in Alberta Ferretti

70 of 73

70 of 73Candice Swanepoel in Etro

71 of 73

71 of 73Andie McDowell in Atelier Versace

72 of 73

72 of 73Tilda Swinton in Chanel

73 of 73

73 of 73