This week, the 96 victims of the Hillsborough disaster were let down yet again after a judge acquitted the two retired police officers and an ex-solicitor accused of altering police statements in what's known as biggest police cover-up in the UK's history.

Once again, families of the deceased are left without justice, as is a city of people blamed for a harrowing disaster they did not cause. In light of this, we revisit Georgia Aspinall words on how the legacy of Hillsborough impacts scousers today.

'I was once having a conversation with a stranger, I told them that I was from Liverpool and they literally turned around and stopped speaking to me. They thought I just had a generic northern accent and as soon as they found out I was Liverpudlian they were just like “nope”’

Grace, like me, is a Scouser living down South. And like me, she’s experienced the unique combination of sexism and classism that women from Liverpool are often subjected to.

For evidence of this, we need look no further than the annualcoverage of Ladies Day at The Grand National. The Daily Mail, along with many others, compiles every image they can find of scouse women drunk and falling over with endless ruminations over their ‘daring’ or ‘plunging’ fashion choices. How do we know this is class-based prejudice? Ask yourself this: do you ever see the same coverage of any other sporting event or festival? No.

I’ll level with you - I am nervous as I write this. As I sit at my computer, I'm already anticipating the rolled eyes merely based on the headline of this article. ‘Here’s another scouser,’ they will think, ‘banging on about Hillsborough again, playing the victim again’. But, you see, that mentality is exactly why I’m writing this in the first place.

Earlier this year, Topman was forced to withdraw a long sleeved t-shirt from their shelves. It was red - the colour that embodies Liverpool’s identity as a city famous for football - with the number 96 on the back – the number of people who were killed at Hillsborough - and bearing the slogan ‘What goes around comes around’ on the sleeves.

When I saw it, I instantly recoiled. ‘Surely it wasn’t intentional’ I thought, ‘SURELY a global fashion company wouldn’t intentionally mock the deaths of 96 people’. Maybe I’m being naive to assume it was a genuine mistake, but one thing I’ve realised in my experience as a scouser living down south is that the majority of people do not care about Hillsborough.

What happened at the Hillsborough disaster?

For those who don’t know what happened which, in my experience, is a worrying number of people, I’ll briefly explain:

In April 1989, thousands of people arrived at a football match between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest at Hillsborough stadium in Sheffield. With overcrowded entry points for Liverpool fans and without enough police or stewards filtering people into the stadium, the crowds were in chaos and getting dangerous. Chief Superintendent David Duckenfield ordered a gate to be opened that led thousands of Liverpool fans into two already congested 'standing-only' pens. As more supporters piled in, unaware that the front of the pen was too full, a human crush occurred. 94 people died during, two more in hospital and more indirectly over the years- almost 800 were injured.

It has since been found that while the crush was occurring, the policedid not immediately respond and when people in it attempted to climb over the fence they were batted back down. When fans were finally able force one gate open, they were branded as ‘hooligans’ attempting a pitch invasion. When police finally did respond, only a handful of paramedics were brought onto the pitch, with only one ambulance of 42 waiting outside the stadium allowed onto the ground - told they couldn’t go on because there was 'fighting'. People on the pitch died because medical help was withheld, only 14 made it to hospital and a child as young as 10, Jon-Paul Gilhooley, was lost. The true extent of the horrors experienced that day were later told in Daniel Gordon's 2016 documentary, Hillsborough.

The next day, The Sun printed their notorious front page that read ‘The Truth: Some fans picked pockets of victims, some fans urinated on the brave cops, some fans beat up PC giving kiss of life’. It was the beginning of a narrative that blamed Liverpool fans for the crush, as the largest police and government cover-up in history began to unfold. Police started to give false statements and feed misinformation to the press. It wasn’t just The Sun, other newspapers like The Times, Sheffield Star, Yorkshire Post, in fact almost everyone that reported on the disaster blamed the fans for the crush- bar the Liverpool Echo.

What ensued after Hillsborough was a 27-year legal battle for justice, finally won in 2017 when six people were charged with offences ranging from manslaughter by gross negligence, to misconduct in public office and perverting the course of justice. However, it was later announced that Duckenfield was found not guilty of manslaughter - despite being in charge on the day. Meaning, no one will be held accountable for that 'gross negligence'.

Hillsborough is an integral part of Liverpool’s history. Not just because it was such a huge tragedy, where near every one you meet in Liverpool will have had a family member or friend lost there, but because it became the epitome of the anti-scouse narrative that Liverpudlians still shoulder to this day.

The way in which the media blamed the Liverpool fans that day, painting them as so immoral so as to steal from their own dead, cemented a stereotype of Liverpudlians that had been slowly growing with the decline of Liverpool’s economy and the Toxteth riots in 1981. Back then, those living in a heavily deprived area of Liverpool - forced into decline by the government - who were also fighting racism within the police, led to the media characterising all scousers' as criminal and militant. The following decade saw Liverpool, once a mecca for economic growth, diminish in the face of new technology, and Liverpudlians paid the price.

With a government contemplating leading Liverpool into ‘managed decline’, Hillsborough came at a time when it served their interest for the media to paint the city as full of convicts. According to post-graduate research student Abigail O’Connor, this was the very message the government wanted to send to justify their lack of economic support for one of the UK's major cities. For her, ‘the truth’ that the government wanted to sell about the disaster, was the one that came out.

‘It’s no coincidence that the Hillsborough narrative happened on the back of Thatcher saying she wanted Liverpool to decay,’ she tells me, ’you’ve got to look at the context of it at the time, that’s why the media were able to speak about the fans the way they did and why it still carries on now.’

Liverpool suffers massively from territorial stigmatisation, the idea that people in a particular area are undeserving because of its reputation.

‘There’s a theory called territorial stigmatization, that says people who live in an area are undeserving of anything because of its reputation, which Liverpool suffers massively from’, she explains, ‘the media were able, through their language, to delegitimise Liverpool supporters to make them seem like the scum that they said they were.’

It’s what ‘justified’ Thatcherism and what continues to enable the government to disproportionally underfund Liverpool. By 2019/20, the central government will have reduced the City Council’s spending power by 24.5% since 2010/11, compared to a national average of 13.7%. That means that local government would be £71.6million better off were their budgets cut in line with the rest of England. There are home counties that actually had their spending power increased during the era of austerity, while Liverpool continued to lose millions.

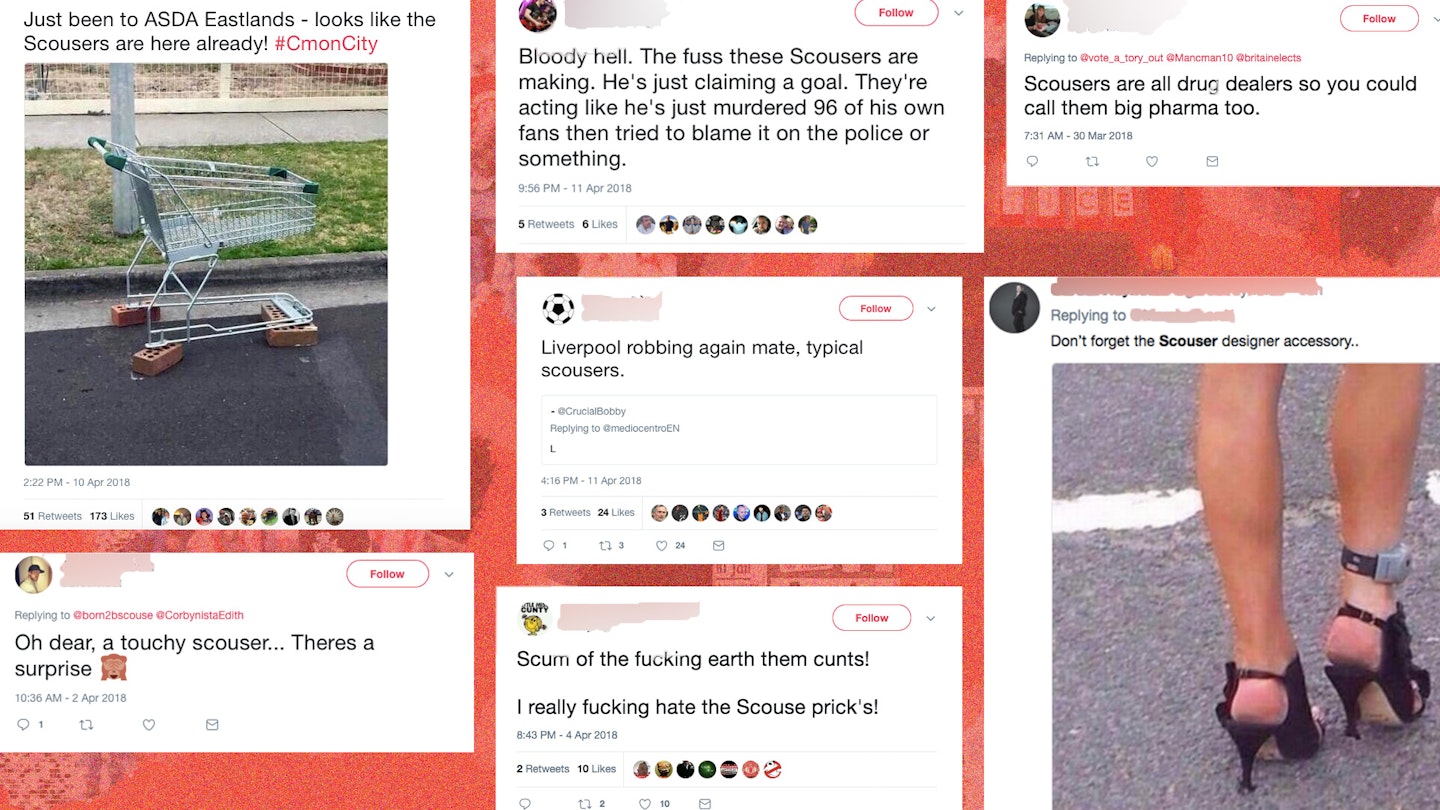

It’s not only Liverpool's local government that suffers, unable to provide the services people desperately need. The bias scousers face continues to feed the stereotypes that were burned into people’s minds with the media coverage of Hillsborough. Whether it’s the archaic jokes about stealing tires, strangers refusing to engage with you upon hearing your accent, being told ’96 wasn’t enough’ online, or the implicit assumption that you’re working class, those from outside Liverpool continue to make false judgements about scousers.

And while many simply brush off stereotyping as a frivolous concern, just as they brush off the Daily Mail headlines from the Grand National as ‘a bit of a laugh’, the stigmatization scousers face matters - because these judgements have a huge impact on the lives and careers of young women from Liverpool today.

‘My current manager is from the midlands,’ says Valerie, who inspects schools for a living, ‘she observed me giving feedback to a management team recently and later said, “don’t take this the wrong way, but your accent sounds aggressive”, and so she marked me down for professionalism.’

Grace experienced a similar set back when applying for colleges at Oxford University. ‘I went to a Summer school at Eton, where one of the professors had told me not to apply for the Oxford College I wanted to because that one was “really difficult, and you should apply for the lower ones so you get in”,' she recalls, ‘I’m as good at Latin as anyone else, so I asked my teacher back home and he said “to be honest, he will have seen posh boys from Eton not get in there. There’s no doubt in my mind he thinks you won’t get in because you’re a young woman from Liverpool”. I was 16, that’s the first time I had to confront the fact that I was from Liverpool and that’s something that people didn’t like.’

Even in government, these incidents happen to the most esteemed people in Liverpool, Ann O’Byrne, Liverpool’s former Deputy Mayor, tells me. ‘People will talk to me and say “I didn’t expect you to be that bright or come up with that argument”, she says, ‘I’m very proud of being working class. The fact that I’m a woman usually in a room full of men, with this accent, and as Labour representative, we mix with a lot of Tory and Lib Dem representatives, their view is that we’re all thick.’

Not only are we 'thick', 'aggressive' and deemed unworthy of conversing with, if we dare speak up about any of the above, we’re ‘whingeing scousers’. That’s the most notable stereotype of Liverpudlians, and according to Abigail - who is herself a southerner - it’s the most damaging.

‘It’s one of the most pervasive representations of scousers,’ she tells me, ‘in reality Liverpudlians have been hit with so much over the years, Thatcherism, the bedroom tax, one-pound houses, the industrialisation.’

Scousers had to stick together because no one else would support them.

‘Scousers had to stick together because of all that, because no one else would support them’, Abigail continues, ‘so they had to create their own identity, because they had no one else, but then the irony of it all is that southerners are angry at them for doing exactly what they made them do.’

Abigail explains that it’s not just anger though, it's a combination of jealousy, an inability to relate to Liverpool's strong identity and a class-based hatred. You can see that in the way stereotypes of scousers prevail despite the city being regenerated with a beautiful town centre, thriving independent business community and filled with the friendliest people in the UK.

Indeed, the assumption that everyone from Liverpool is working class is, in its own right, prejudiced. This however, is the subtle bias most scousers who move away encounter. Grace tells me about a time she met a tutor at Oxford who asked her the age old question ‘are you a red or a blue?’ upon meeting. She explained her dad supports Everton but her mum Liverpool, to which he responded ‘oh, I can just imagine you all on derby day crammed into your tiny little living room watching it.’

The assumption that we’re all living in the 80’s, packed into one-pound houses, is prevalent everywhere you go outside Liverpool. Niamh, a fellow emigrant to London, experiences the same awkward encounters. ‘I've got a first-class degree from a Russel Group university' she says, 'but in work people are shocked when I tell them that. They assume you must be first generation uni and got lucky to get out of the city.’

It’s this awkward class-based assumption which, coupled with the everyday sexism young women face, puts those of us from Liverpool in a double bind. It goes without saying that if you’re also facing racism, homophobia and/or ableism, you’re even more likely to deal with discrimination. And according to Ann, scousers will always be subject to it regardless of how incredible the city becomes.

‘It’s as though you can never escape any of it’ she tells me, ‘[the media] will always find a way. It’s like Ladies’ Day at the National, it’s just a way of putting down Liverpool women. It's just a way of laughing at us, "Ooh there you are thinking you can dress up, don’t forget what you are".'

‘A massive part of this is about class for me’, she continues, ‘when Princess Diana died and the whole country mourned, that was seen as acceptable. But the when innocent young people died, we were seen as victims [for continuing to mourn]. Diana is this middle-class, articulate, attractive woman so that was okay. The fact that these were football fans– branded “hooligans” and “second class citizens”, made it a “working-class issue”. Therefore, they were “part of the problem”, and that carries on right up until 2017 and the fact that the families had to fight for so long.’

Abigail agrees, noting it as a reason why the fight for justice over Hillsborough encountered so many obstacles. ‘It’s hugely related to class,’ she says, ‘what I argued in my research was that in order to claim that you’re telling the truth, you have to have some sort of power or knowledge base, and the government, the police, upper classes, they have that.’

Growing up in Liverpool, Hillsborough is encoded in your identity. It was and remains the biggest news story about our home and so, even when government ministers like Boris Johnson apologise to our entire city for the havoc they wrought on us, it just reminds us that they didn't care then and - through their actions - it's obvious that they don't actually care now. It only reinforces the sense that we don't belong with London's elite. In fact, it all amounts to a feeling that you belong in only one place: Liverpool.

Follow Georgia on Twitter @GeorgiaAspinall