I am an only child, but I have one sister. Well, one that I know of. There are probably more. Confusing, I know. Yet my situation is one shared by tens of thousands of donor-conceived people in the UK alone. According to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, the number of women using egg donors has risen sharply to just under 4,000 a year. Meanwhile, around 2,000 children are conceived annually in the UK with the help of donor sperm. And I, unknowingly, was one of them.

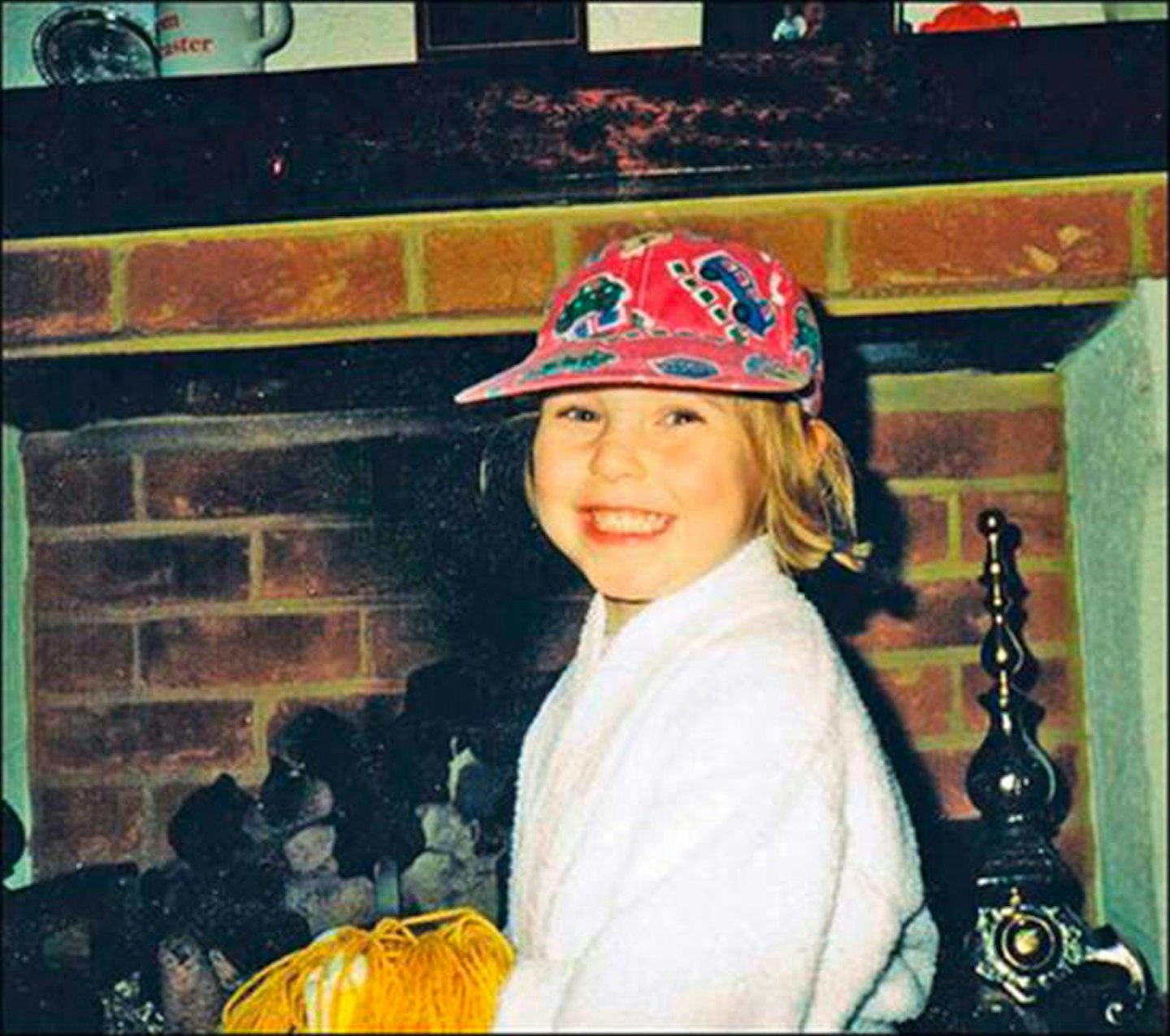

I grew up happy, imaginative, and content with my own company. While other friends had siblings, I had a tight-knit unit of three: me, my mum and my dad. But when I was 13, my parents sat me down across our small kitchen table. They had something to tell me: ‘Your dad may not be your dad.’ I am far from the first child to be told such a revelation. But though the words may vary, and the families saying them take many different forms, it still packs the same bitter punch. There was no affair. Nothing like that. But there were secrets.

‘We wanted so badly to have you,’ Mum explained. But they had struggled. After years of trying, they opted for IVF, mixing my dad’s sperm with that of an anonymous donor – a method that was in vogue at the time. There was a 50-50 chance I was not Dad’s biological daughter. In an instant, her words transformed everything I thought I knew about my identity, my family and my place in it.

In the days and months following, my new reality would hit in waves, each one rolling in like a fresh punch in the stomach. I would spend hours staring into the mirror, analysing my features, and trying to work out which parts of me might be made up of a man I’d never met... who I would probably never meet. Suddenly, my reflection looked totally different. Half of it was wrong. Two years later, aged 15, I asked my parents if we could do a DNA test. The results arrived one morning – two sheets of paper with a jumble of data and jargon. It confirmed my worst fears.

That evening, I waited by our front door until Dad got home from work. I had often stood there as a child, watching the driveway intently for him to pull in before I would run out to be swept into a giant hug. This night, the hug would feel very different. He would hold me as we cried, both mourning a relationship that was simultaneously unchanged and yet changed forever. Before we started this journey, I’d only seen him cry once – when his father died. My guilt hit harder still because Dad had never truly wanted to do the DNA test. I had insisted. But there was hurt too, and I wasn’t sure where to direct it. Even at 13, I understood that my parents had just been waiting for the right age to tell me the truth. In fact, telling me at all went against the advice they’d been given when undergoing IVF.

It was a time when the medical community could not have imagined the landslide of affordable at-home DNA tests. A recent study found that up to 30,000 are now being performed each year, making family secrets such as donor conception all but impossible to keep. A couple of decades ago, medical professionals were promising donors anonymity. my family, how many times he donated, or how many children resulted from it. I was conceived the year legislation changed making UK sperm donors traceable. But it still took me a long time to find my half-sister, because I had no records to help my search.

Instead, we both paid to give our DNA to a giant corporation. Our match rolled in in November 2017, bringing a freefall of positive and terrifying emotions. Unlike me, my sister grew up with two mums, so the role of an unnamed sperm donor was always obvious. We met in Central London two weeks later, laughing at our similar mannerisms, which hint towards a man we do not know, but who makes up half of both of us. In her, I see the features I once searched for in my own face – clues to what our biological father may look like. I’m lucky that my parents have always respected my right to find out. They stood by as I ordered DNA test after DNA test, and when I finally got a match, they welcomed my new sister with open arms.

But she and I have no idea how many other half-siblings we may have. We may never find them, because many will never know they are donor-conceived at all. There are no laws to make parents who use donors tell their children about the circumstances of their conception. Many will never inform them. Yet, the vast majority of donor-conceived people I have spoken to believe in our right to know.

On an emotional level, that shortfall in honesty deprives children of the opportunity to find kin, or attain accurate medical records. But it is particularly horrifying when you consider that sperm donors in particular tend to donate multiple times in one area, and half- siblings inevitably grow up in the same towns, close in age, attending the same schools. It’s not unheard of for donor-conceived siblings to accidentally date. Regardless of how we find out, the general consensus now is that those who find out later in life are impacted in a more negative way. Many, understandably, report a loss of identity and feelings of betrayal.

Recently, the mother of donor-conceived children asked me when she should tell them. The answer from me – and most of the people I have spoken to – is ‘Tell them yesterday!’ Ultimately, though, my love for my dad never changed. He is my father in every possible meaning of the word, and none of this was ever about changing that. It was just about filling in the blanks

You can follow Louise on Twitter @LouiseJoUK