Last week, a beauty bomb was dropped on influencers. The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) ruled that when they create sponsored posts to sell us skincare or cosmetics products, they’re no longer allowed to use beauty filters.

Why? Because adding a filter that enhances an influencer’s natural looks – smoothing skin, brightening under-eyes and contouring cheekbones – while showing off a product that ‘changed their life’ isn’t exactly ethical marketing.

The move follows an eight-month-long campaign to end the use of beauty filters in advertising, dubbed #filterdrop, by makeup artist and curve model Sasha Pallari. ‘The amount of people that will no longer compare themselves to an advert that isn’t achievable without a filter is going to be prolific,’ she wrote on Instagram in response.

For some influencers, it will mean a big change. But for countless people ‘influenced’ by them, it’s a blessing. Particularly since, in this ever-so-virtual world we’re all still stuck in for the time being, many of us are feeling more self-conscious than ever. Not just because we’re all seeing our reflections so much more than before on video calls, but on social media, we’re not actually seeing many ‘real’ - aka unfiltered - faces. Looking at our own faces in actual mirrors then can only pale in comparison, even when you know it’s all fake.

I found myself ‘testing’ filters commonly used by my favourite influencers quite often over lockdown, turning them on and off to judge my face against what it ‘should’ look like. Having been so reliant on Snapchat filters just a few years ago – before going cold turkey when it became apparent I couldn’t take a picture without them – I knew it was an unhealthy habit. And yet, boredom and video chat self consciousness meant I couldn’t stop myself.

I’m not alone, either: a recent study by Parliament’s Women and Equalities Committee found that more than half of UK adults feel worse about their body image during lockdown. Reasons given range from seeing more adverts for products to change your appearance (now that we’re consuming more media, being at home all the time) to staring at ourselves in video meetings all day. That’s on top of research from Girlguiding in August last year, which found that a third of girls and young women will not post selfies online without using a filter.

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that many of us have been becoming more reliant on beauty filters ourselves. Because of course it’s not just Instagram these days – you can add them to Zoom calls and FaceTime meet-ups, too.

‘Without our basic social needs being met, we, as humans, will look for other ways of getting “fed” from our significant others. In lockdown, that means great pictures and thus positive responses on social media,’ explains psychological therapist and author Michael Padraig Acton. ‘In turn, people then wonder, “Would it not be great to have a filter make us look and feel just that bit better about ourselves?” We would be silly to think that we are not going to use what is at hand to help us during this difficult time.’

He welcomes the ASA responding to this worrying trend when it comes to advertising cosmetics. ‘It is criminal to take people’s money and fraudulently sell something that will not get the results promised. It is also dangerous to give vulnerable and young people a benchmark to which they feel they need to compete. This can lead to severe low self-esteem and dysfunctional conditions, such as eating disorders, body dysmorphia and depression.’

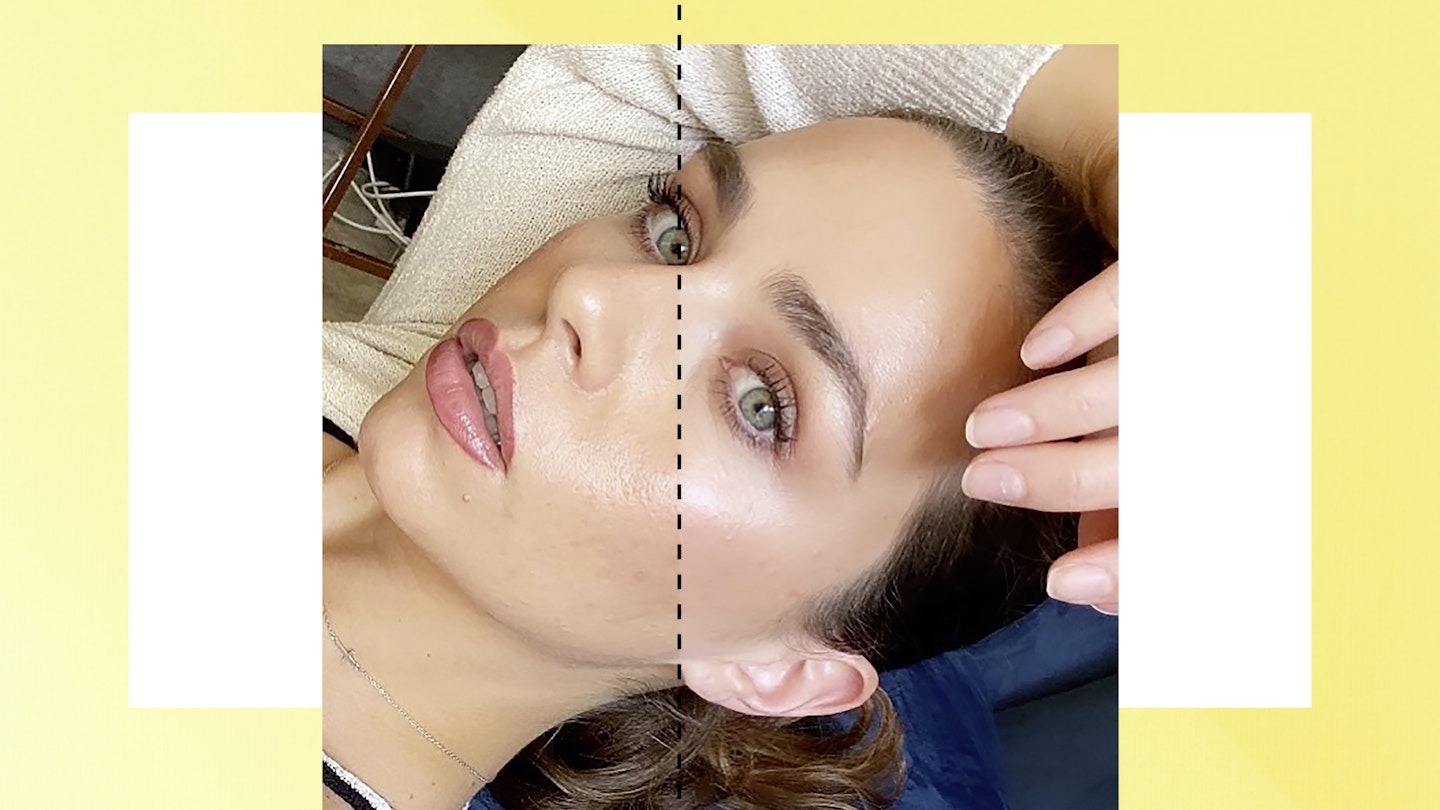

The application of filters by influencers is increasingly sophisticated and subtle.

With that in mind, and following the success of Pallari’s #filterdrop campaign, it seems as though a backlash against the increasing beauty filter use is coming, at least legislatively. So does it mean the beginning of the end for our own filter use, too? Not necessarily, according to Katie Thompson, a doctoral researcher at Liverpool University, who is writing a PhD on our use of filters and selfie-editing apps.

‘Filters and editing tools are firmly enmeshed into the cultural fibres of digital spaces like Instagram,’ she explains. ‘As a result, I think the recent ban may prove difficult to regulate, as the technology surrounding editing tools and apps is innovating rapidly, and their application by influencers is increasingly sophisticated and subtle. That being said, I think the ASA regulation is a positive step in the right direction, and will at the very least help to raise public awareness of these practices.’

And perhaps get us all to question why we feel the pressure to use filters, too.

Read More:

More Honesty Please! Why 2021 Is The Year To Get Real About Beauty

Using Instagram and Snapchat Filters Made Me Hate My Actual Face