In last night's Love Island, a recurring theme reared it's ugly head yet again. When Belle Hassan chose to forgive Anton Danyluk for his toxic 'laddy' behaviour, she began questioning her own behaviour and apologising for the way she confronted him, pointing to her own insecurities as the reason she got so angry. In a scene that saw viewers rush Twitter with commentary about how she wasn't in the wrong at all, the conversation proved a longstanding concern with the way female Islanders respond to bad behaviour from the Love Island men: they always blame themselves.

‘Can you give me some feedback?’ was the fateful line we saw earlier in the season, when newly dumped Amy Hart made that request of everyone’s least favourite professional ballroom dancer, Curtis Pritchard. Female viewers across the country wailed a collective, ‘Noooo!’ at the sight of a perfectly nice woman politely asking the man who had spent four weeks pretending to like her, then ditching her, what she could do to make sure her next boyfriend didn’t do the same was excruciating.

Watching him completely ignore the accepted norm of muttering, ‘It’s not you, it’s me’, and instead go on to give her a list of her failings was even more galling. While we might all have hoped that Amy would tear him to shreds before making a beeline for the far more mature Ovie, she did what so many of us have done before and made Curtis’s behaviour her fault. Even her departure last week was designed to make sure she wasn’t getting in his way. After telling him he was a ‘good person’ and that she loved him, she said, ‘You’re not going to be happy while I’m still here.’

The narrative appeared again, across multiple different conversations, with Michael and Amber. When Michael went from being the most loyal man in the villa to love ratnumber one, we saw Amber desperately pleading with the girls to tell her what she’d done wrong and accepting Michael’s assertion that he’d strayed because she wasn’t willing to trust him. An instinct, it turned out, she was right to heed. Even Maura, usually 5ft9in of pure self-esteem, has spent this week wondering if her lack of suitors is down to her rather than the fact that there simply isn’t a man in the villa who can match her.

And, as much as I wanted to storm the island and make them all listen to Lizzo on repeat, I couldn’t help but find myself recognising some of my own behaviour in the girls. In my twenties I spent far too much time agonising over the things I could do to bring a rogue ex-boyfriend back to me – never mind that by the time I’d done all of them I’d have changed myself so much he probably wouldn’t recognise me. But this behaviour doesn’t just show up in romantic relationships – and it isn’t restricted to 20-somethings. We’ve been so indoctrinated into the cult of self-improvement that we’re doing it in all areas of our lives. When a project at work hasn’t gone as well as we hoped, who among us hasn’t agonised over what might have happened if we’d made it just a little bit more perfect? Or, when a friend or colleague seems out of sorts, wondered if it could have been something we said?

These blame pains, however, don’t seem to be afflicting the boys. Recently, I was chatting to a male friend of mine about a job interview he’d had. ‘I didn’t get the job,’ he shrugged. ‘I think I was just too expensive for them.’ There was no wondering whether he might have got it if only he’d had a few more years’ experience, or beating himself up for not having the right answer to the final question. So convinced was he that the problem lay with them rather than with him, that when he found out he’d been rejected he just sent them a polite note thanking them for their time and asking them to get in touch when they had a more suitable role. Unlike every woman I know who failed to get her dream job, there was no request for feedback.

So why are women so intent on blaming themselves for everything? Research from Northumbria University has confirmed that while men tend to externalise their mistakes – that is, blame anything other than themselves for it – women tend to internalise it. My theory is that this stems from the socialisation of women as peacekeepers. From an early age we’re taught to look out for other people’s feelings, to avoid making mistakes or upsetting others, and so when we see pretty much anything going wrong we instantly turn the blame on ourselves. But this self-flagellation is getting in the way of real growth and, frankly, happiness.

We could behave like the men on Love Island and deny that anything is our fault, ever – watching them all wiggle out of responsibility for their actions has been a depressing masterclass in bending the truth – but I suspect we’d be better off finding a middle ground. Ultimately, we all need to learn to accept responsibility for our part in situations going wrong – and we need to hold others accountable for theirs, too. Hopefully this latter part is something Amy and Amber will learn when they reflect on their Love Island experience in the future. After all, it takes two to tango. Something you’d think Curtis would know.

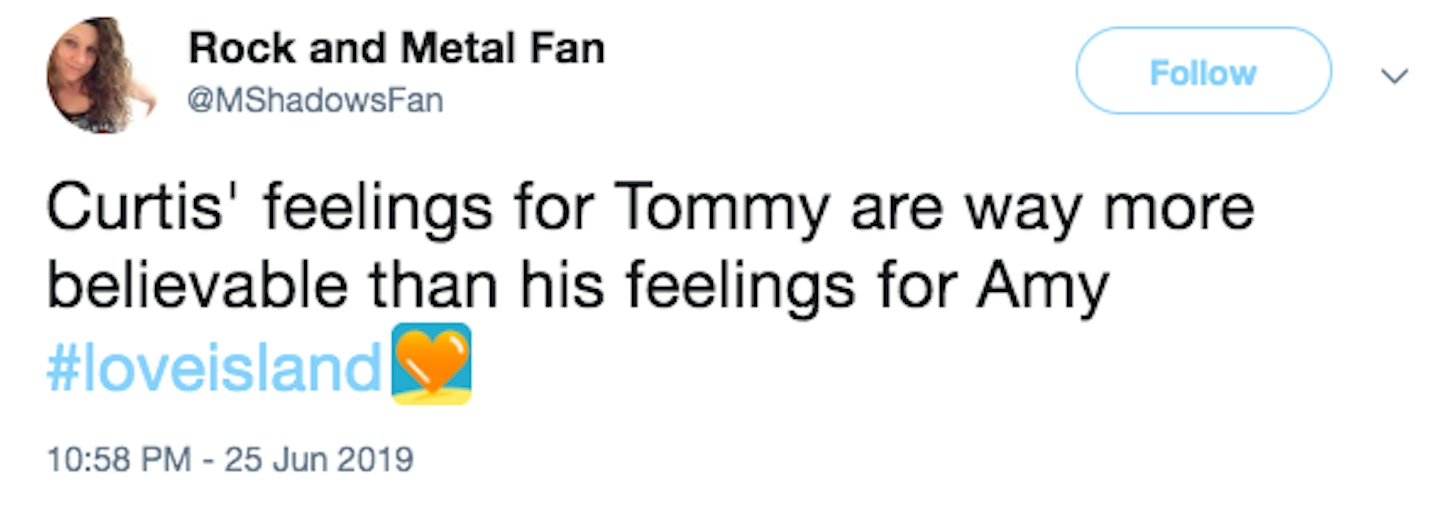

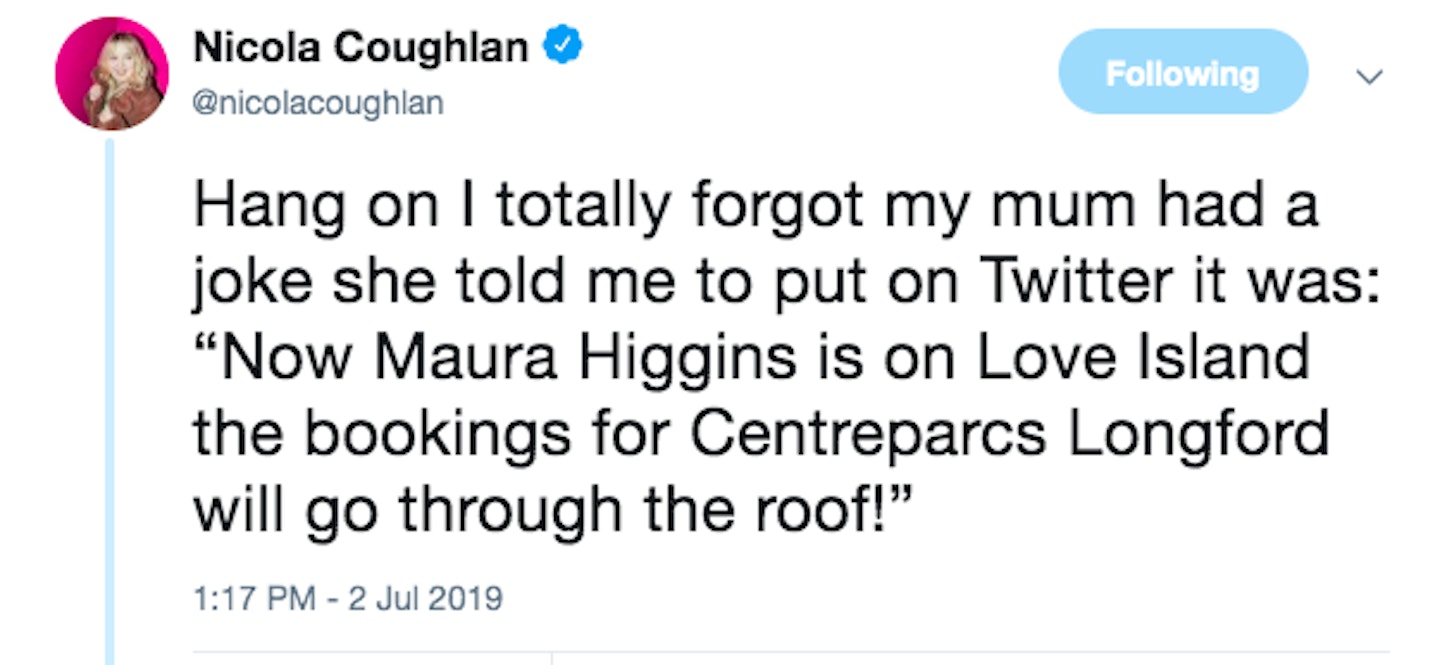

Read more: The best Twitter reactions to Love Island 2019...

Click through to see the best Twitter reactions to Love Island 2019...

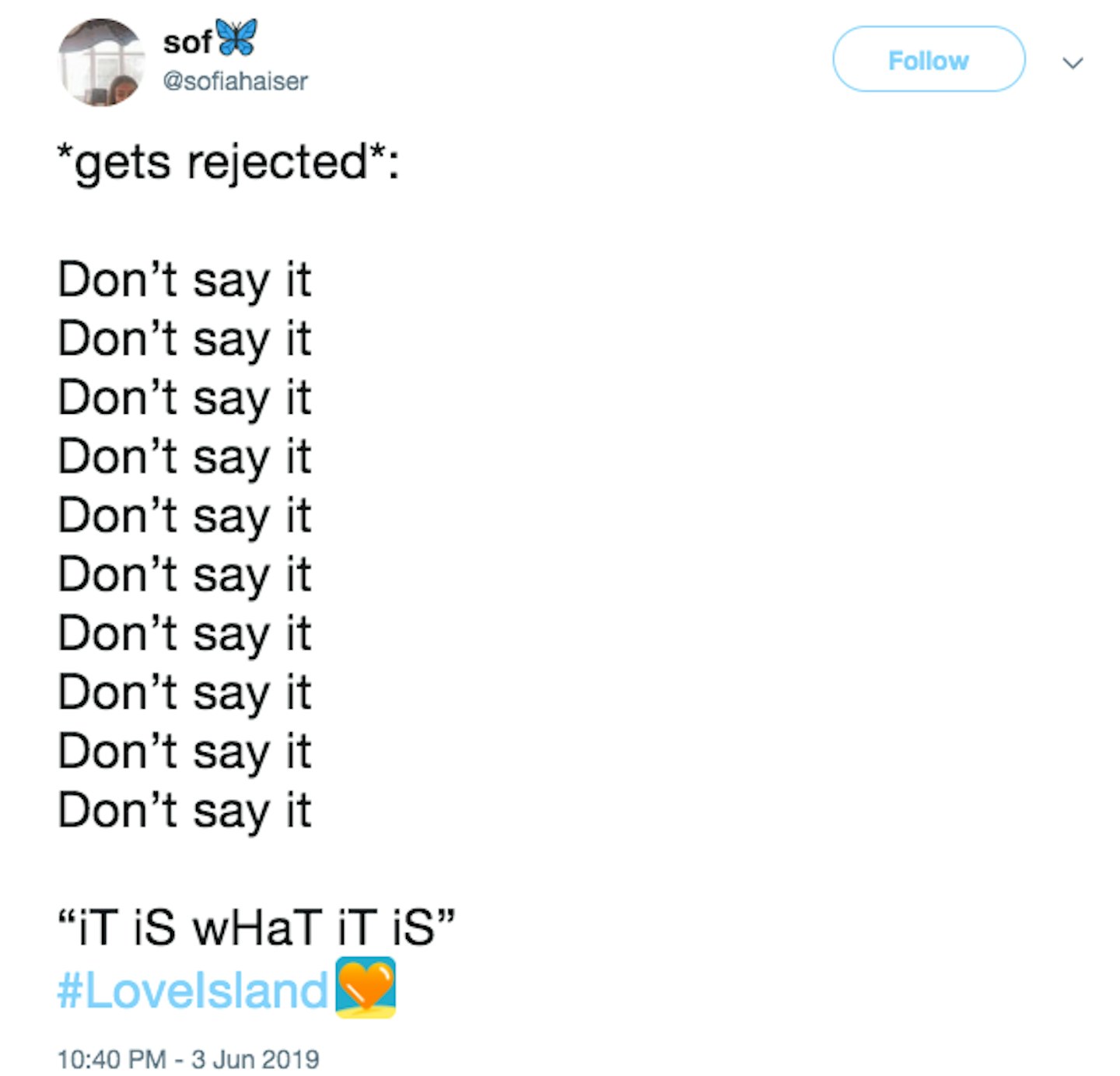

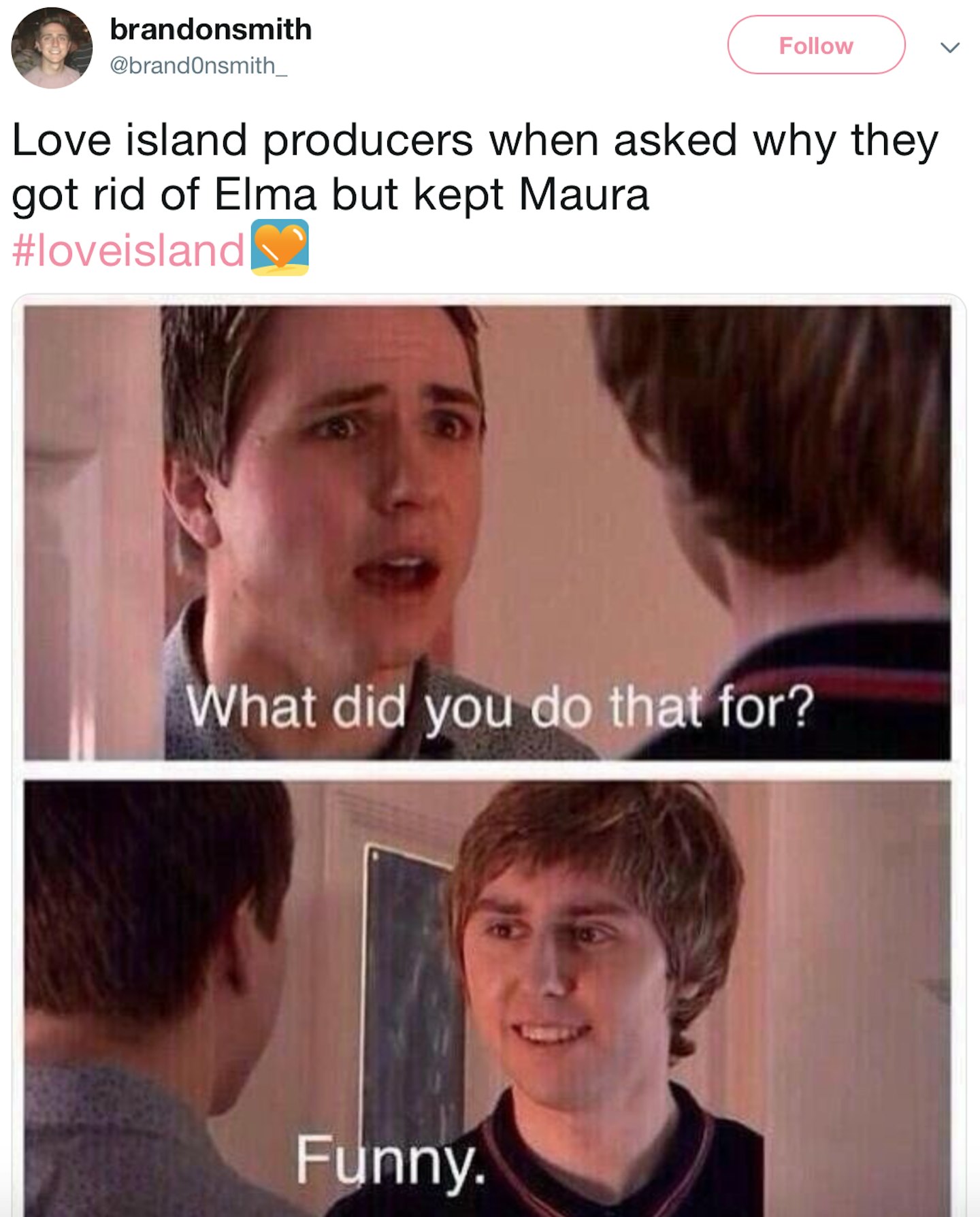

1 of 36

1 of 36love island twitter

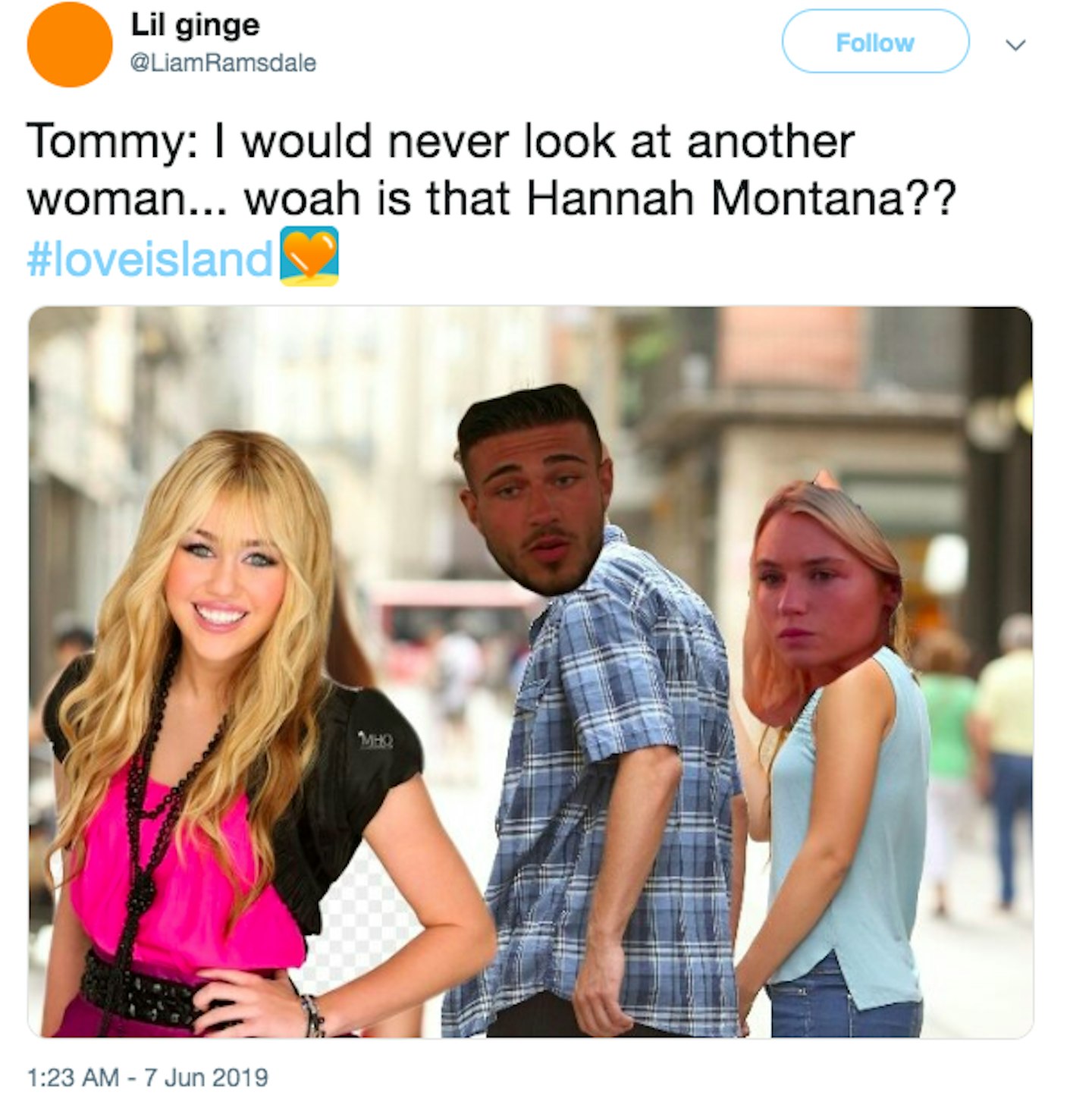

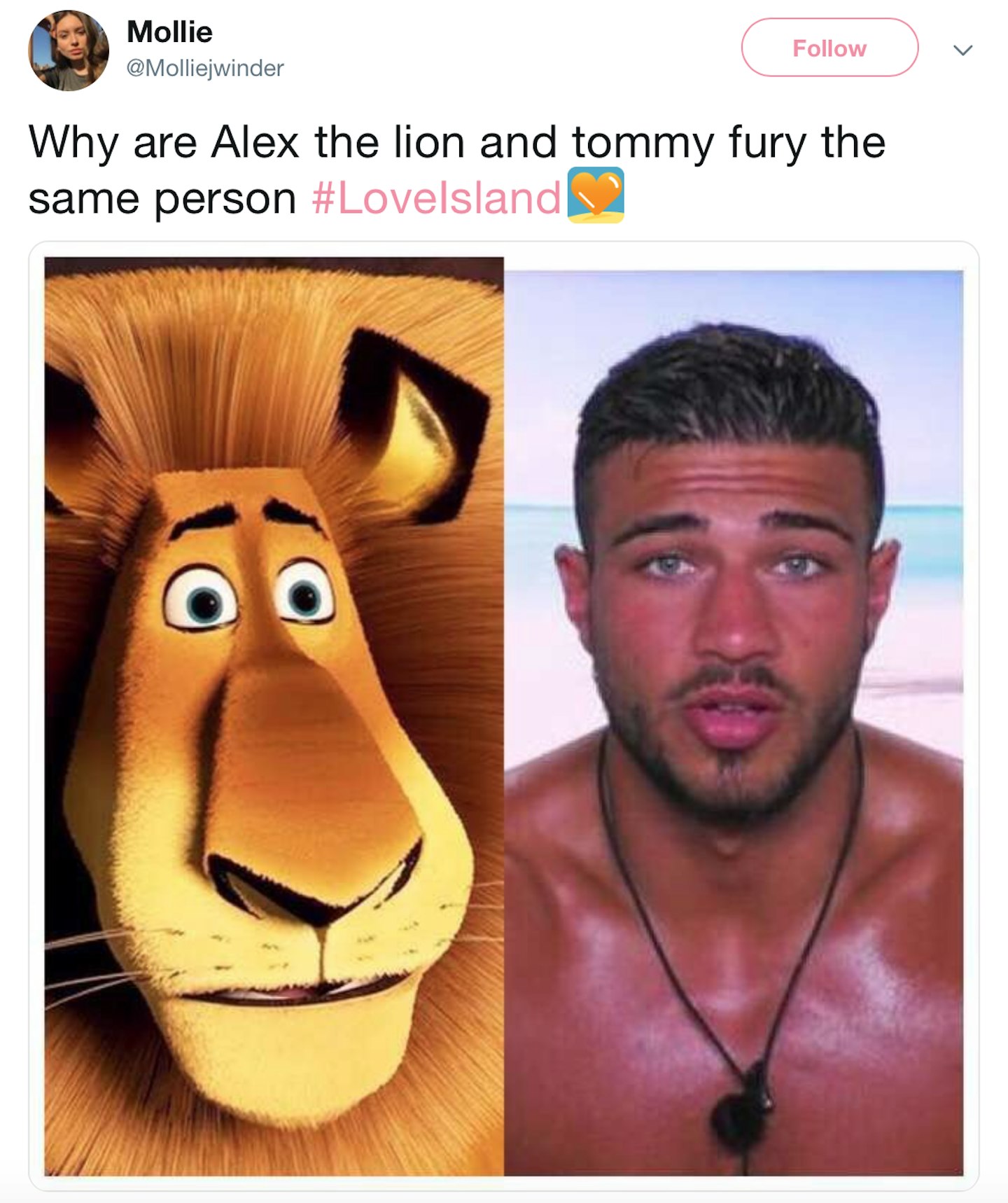

2 of 36

2 of 36love island twitter

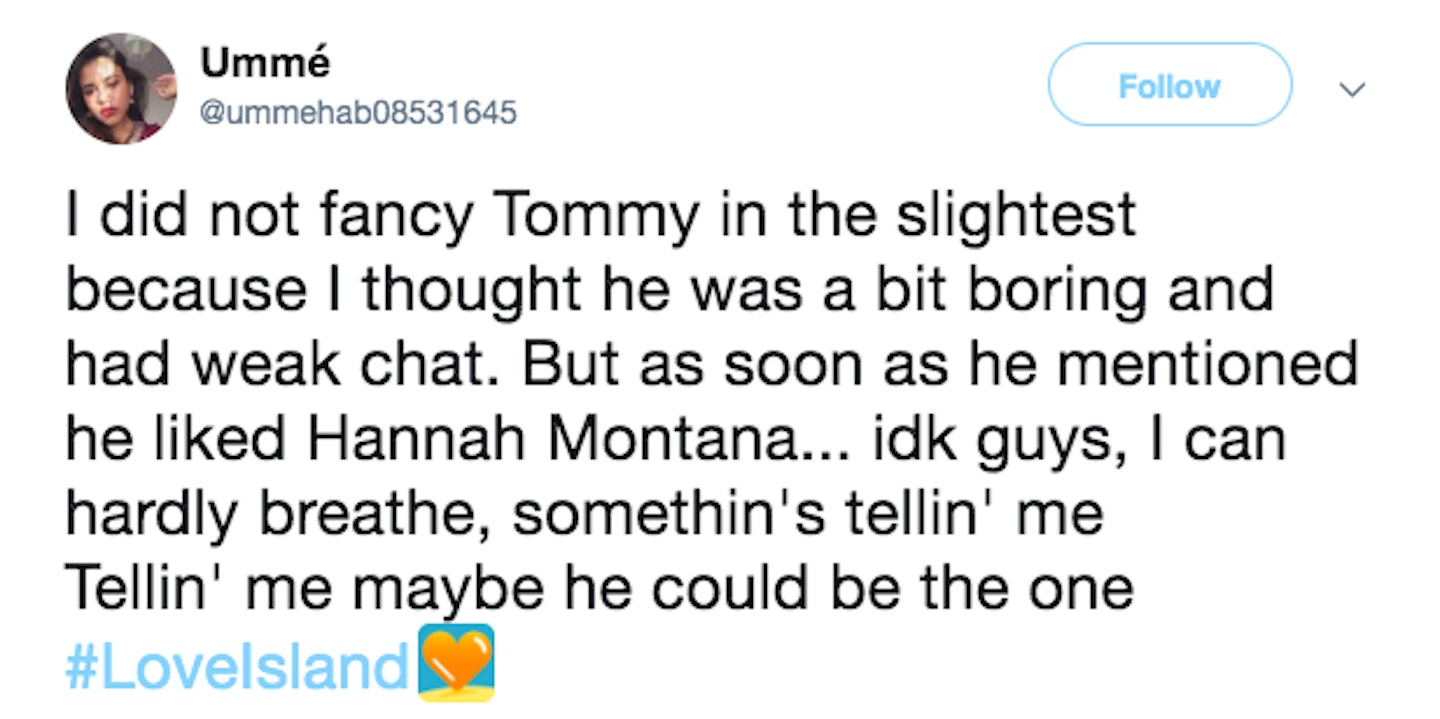

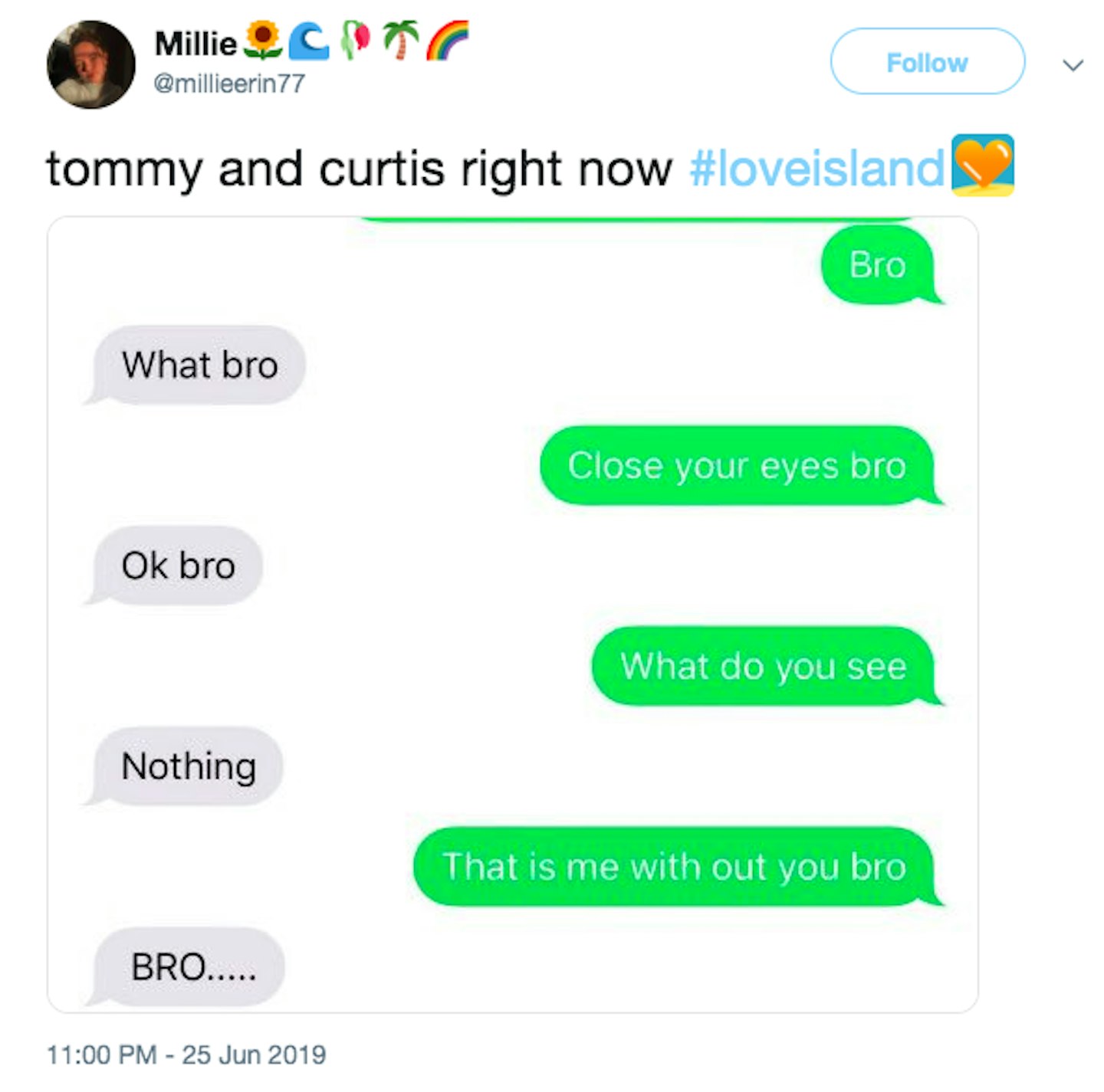

3 of 36

3 of 36love island twitter

4 of 36

4 of 36love island twitter

5 of 36

5 of 36love island twitter

6 of 36

6 of 36love island twitter

7 of 36

7 of 36love island twitter

8 of 36

8 of 36love island twitter

9 of 36

9 of 36love island twitter

10 of 36

10 of 36love island twitter

11 of 36

11 of 36love island twitter

12 of 36

12 of 36love island twitter

13 of 36

13 of 36love island twitter

14 of 36

14 of 36love island twitter

15 of 36

15 of 36love island twitter

16 of 36

16 of 36love island twitter

17 of 36

17 of 36love island twitter

18 of 36

18 of 36LOVE ISLAND TWITTER

19 of 36

19 of 36LOVE ISLAND TWITTER

20 of 36

20 of 36LOVE ISLAND TWITTER

21 of 36

21 of 36love island twitter

22 of 36

22 of 36love island twitter

23 of 36

23 of 36love island twitter

24 of 36

24 of 36love island twitter

25 of 36

25 of 36love island twitter

26 of 36

26 of 36love island twitter

27 of 36

27 of 36love island twitter

28 of 36

28 of 36love island twitter

29 of 36

29 of 36love island twitter

30 of 36

30 of 36love island twitter

31 of 36

31 of 36love island twitter

32 of 36

32 of 36love island twitter

33 of 36

33 of 36love island twitter

34 of 36

34 of 36love island twitter

35 of 36

35 of 36love island twitter

36 of 36

36 of 36