‘You bring the corsets, we’ll bring the cinches, no one wants a waist over nine inches.’ In the award-winning Broadway show Six The Musical, this satirical line was used to condemn unrealistic beauty standards in the 1500s. Now, it’s being used on TikTok as part of the viral ‘9-inch waist challenge’.

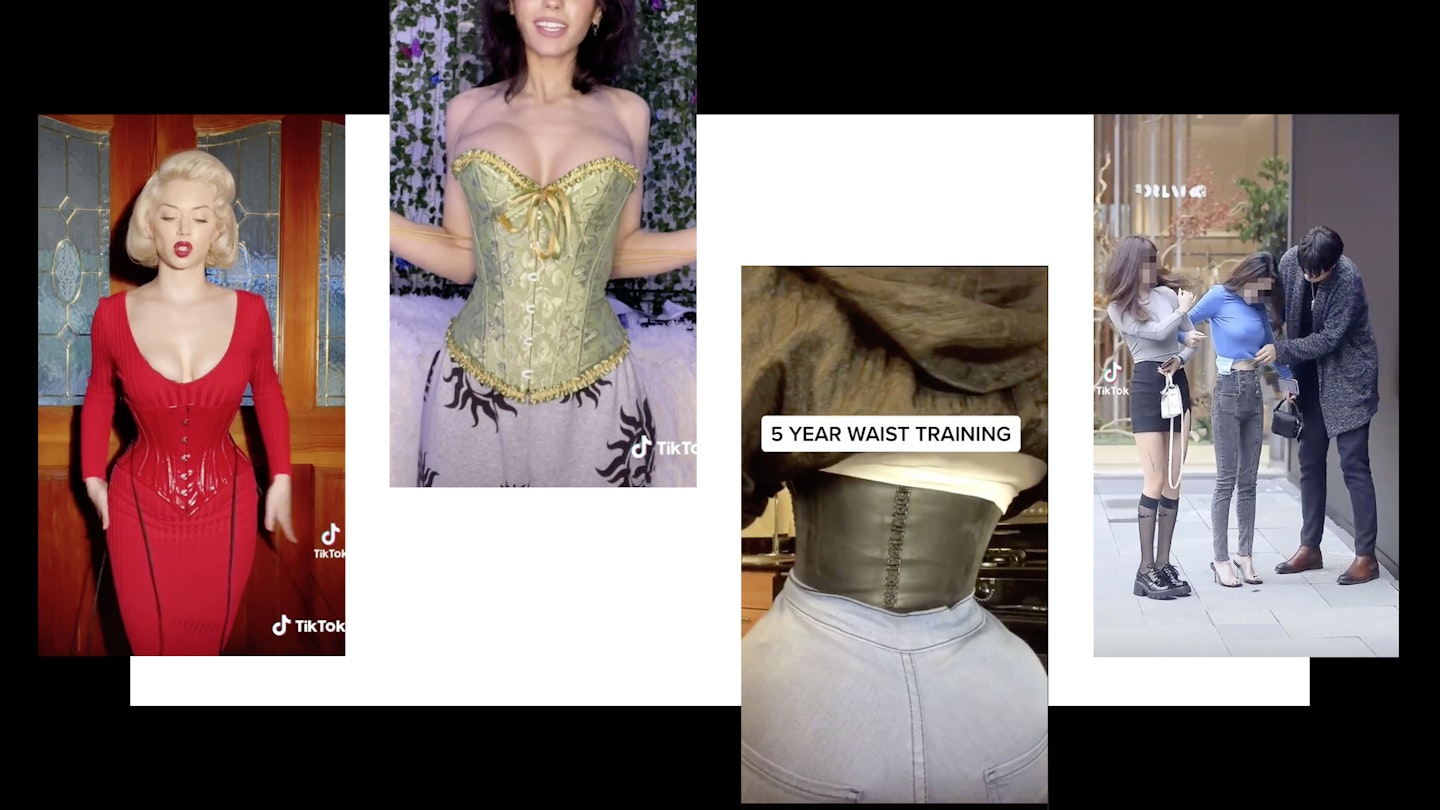

I hear it via my For You page as I’m scrolling through TikTok before bed. Bianca Blakney, who has over 4.1 million followers, appears on my screen in a red dress and corset miming to the song. As the words ‘9 inches’ are uttered, she pulls the laces of her corset tight, cinching her waist to unbelievable proportions. The clip has 15.2 million views and two million likes.

At first, I think nothing of it and scroll by. But then I see another similar clip, and another. So far, the song has been used in more than 159,000 videos and counting. For users like Bianca, it’s ‘tongue in cheek’ content. But then, challenges like these tend to start that way until they go viral and we realise the message they’re really sending.

In 2016, it was the #A4waistchallenge, where women compared the size of their waist to the width of an A4 sheet of paper (the idea being that your waist should ‘fit’ behind the paper). That recirculated recently on TikTok, according to users we spoke to. Then, last year, it was the #Earphoneswaistchallenge, where you tie your earphones around your waist to test the size – which originated on Chinese social media platform Weibo but, again, found its way on to TikTok too.

Last month, journalist Danae Mercer called out these types of challenges. She posted to Instagram a gallery of nine TikTok videos, some showing women attempting to squeeze through tiny gaps to show off their slender figures, and another where a man tries to tie face masks around women’s waists in public to see if they snap. ‘I want to keep this platform a really happy place,’ Danae wrote in her caption. ‘But when I see eight-year-olds talking about their diets, 13-year-olds sharing their BMI and children wrapping iPhone cords around their waists to check their size, I have to talk.’

For users who are suffering from eating disorders or in recovery, online content like this can be incredibly triggering. Ellie Makin, 17, has been in recovery from anorexia and bulimia since June last year.

‘I think TikTok can be dangerous,’ she tells me. ‘These trends are so damaging for impressionable teenagers and people suffering from eating disorders. They’ve increased in lockdown too. Promoting a 9-inch waist is outrageous. I know children use TikTok, I have seen eight to 10-year-olds on the platform. At that age, they’ll grow up believing they’re different and don’t fit society’s beauty standards, when a 9-inch waist is impossible to achieve.’ (TikTok says users must be 13 or over.)

India Blakemore, 22, who developed an eating disorder 10 years ago and began her recovery last year, agrees. ‘There are many fatphobic trends on TikTok that are unhelpful. It’s hard for me to watch videos like the earphone challenge as I could once do that. I can’t any more due to my recovery.’

Ellie believes that TikTok can be used in a positive way to help with eating disorder recovery. She, for example, posted a video of her recovery on her TikTok account @eatwellwithell (with a trigger warning) that received more than 26 million views and five million likes. India did too (@indiablakemore), receiving five million views and nearly one million likes for her video on ‘beating anorexia’s skinny ass’.

‘I think following creators on TikTok that promote body positivity and self-love really does help,’ Ellie says. ‘But if not used in a positive way, TikTok can definitely lead to people suffering with eating disorders being stuck on triggering content, which will only hinder their recovery.’

And eating disorders are already on the rise due to the strains of the pandemic. According to Beat, the UK’s leading eating disorder charity, there has been a huge increase in demand for their services since lockdown. In February this year, they noted a 170% increase in contacts across all their support channels compared to February 2020. Anecdotally, Beat told Grazia that people who contact them have mentioned apps like TikTok as a factor in their illness – although they believe ‘positive recovery communities’ on social media can also be encouraging for many.

TikTok is, in the main, good at removing content deemed harmful. Unlike when Tumblr was the cool kids’ platform of choice and pro-ana and pro-mia content (which promote anorexia and bulimia as ‘lifestyle choices’) ran riot, harmful hashtags promoting eating disorders are blocked. If you search ‘proana’ or ‘promia’ on TikTok, you’ll be directed to a link for Beat, who told Grazia they work directly with TikTok to advise on creating safer spaces for people affected by eating disorders. TikTok’s community guidelines also explicitly state: ‘Content that promotes eating habits that are likely to cause adverse health outcomes is also not allowed on the platform. Do not post, upload, stream or share content that depicts, promotes, normalises or glorifies eating disorders or other dangerous weight loss behaviours associated with eating disorders.’

The problem is, though, that many of these trends and challenges don’t actively glorify eating disorders. The ones that go viral are not necessarily telling users to change their eating habits, but that doesn’t mean they’re not promoting thinness, weight loss and diet culture. Alongside the tiny waist challenges, there are countless videos of users trying waist-trainers or posting ‘What I eat in a day’ videos – despite being completely unqualified to offer nutritional advice.

Video is also a multi-sensory experience, it captivates the audience more.

One of the best things about TikTok’s algorithm is that it doesn’t require users to have substantial followers or verification to go viral, but when it comes to content like this, that’s a double-edged sword. When a user sees this content on their For You page, it’s almost like talking to a friend. ‘The people you see on TikTok are like you – that can make them more influential because it’s peer-to-peer influence,’ explains Nikita Aggarwal, research associate at the Oxford Internet Institute’s Digital Ethics Lab. ‘There’s a sense of, “Well, if this person managed to get their body like that, I can do that as well.” Video is also a multi-sensory experience in a way that words and photos are not. It captivates the audience more, so can be more influential.’

TikTok’s famously clever algorithm also means almost every video you see feels perfectly aligned with your interests. It’s what makes TikTok so fun to use, but if you’re in an unhealthy mindset, engaging with content that promotes diet culture, it would be easy to become sucked in.

TikTok’s recommendation system, Nikita explains, looks at hundreds of factors in how users respond to videos, including how long we spend viewing it, whether you click “like” or “not interested” and what hashtags you search for. The 15 or 60-second time limit on its videos mean that we interact with much more content than on many other apps, providing tons of feedback.

‘For any recommendation system that is trying to tailor content to a user, a pretty natural consequence is the “filter bubble effect”, where you get a very homogeneous stream of information that’s like, “This person keeps liking and viewing diet content, so we will just show them more diet content”,’ says Nikita. ‘TikTok has built other considerations into their algorithm, though; they also take into account policy concerns like, “What is harmful content?”’ That’s where TikTok’s safety warnings come in, appearing on the bottom of certain videos, and also why certain hashtags are blocked or content removed.

The prevalence of diet culture content, however, is also a byproduct of who is on the app: TikTok’s audience is ageing, but it’s estimated that more than 60% of users are between 10 and 29 – and most are female. ‘The demographic on TikTok might lend itself more to diet culture or appearance-based harm because it’s often younger, female groups who are quite image conscious,’ says Nikita. ‘Any social media app does tend to become some sort of competition about appearances.’

Still, that doesn’t resolve the problem – so what more can TikTok do? ‘It’s not an easy task to know where to draw the line,’ explains Nikita. ‘Unlike very explicitly illegal content, diet culture content is much more of a grey area. The challenge for a company like TikTok is how do you define harm? How do you police culture?’ Removing hashtags is, she adds, ‘never going to be the full solution because you can remove one and hundreds more will come into circulation’.

From the amount of triggering videos still live, it’s clear people have been getting around hashtag blocks.

Tom Quinn, Beat’s director of external affairs, agrees that hashtag blocking can only go so far. ‘From the amount of triggering videos still live, it’s also clear that people have been getting around this. We believe there are further measures that still need to be introduced, such as getting more real people to filter out harmful content.’

According to TikTok, their technology is constantly reviewed and updated to respond to emerging harmful activities. ‘As a platform, we’re focused on safeguarding our community from harmful content and behaviour while supporting an inclusive – and body-positive – environment,’ a spokesperson told Grazia. ‘Some of the recent changes we’ve made include banning ads for fasting apps and weight-loss supplements, increasing restrictions on ads that promote harmful or negative body image, and introducing permanent public service announcements on hashtags like #whatIeatinaday to increase awareness and provide support for our community.’

That’s all well and good, but for users like India, it’s not enough. ‘Making videos to show my progress helps me a lot on TikTok,’ she says. ‘But lots of things slip through the gaps. TikTok is meant to be my escape – so I don’t want my escape to be full of what I’m already living.’

If you’re worried about your own or someone else’s health, you can contact Beat, the UK’s eating disorder charity, 365 days a year on 0808 801 0677 or beateatingdisorders.org.uk

Read More:

Things You Only Know If You’ve Been In Lockdown With An Eating Disorder