Laws around cyberflashing, revenge porn and deepfakes will all soon be revised by the government under a new review of image-based sexual abuse law, potentially making sending unsolicited dick pics illegal.

The review, which has been long campaigned for by activists, could also give victims of revenge porn the same anonymity rights as current victims of sexual abuse – a change Love Island’s Zara McDermott called for last year after being victim to it herself while appearing on the TV show.

Currently, sharing explicit images without consent is categorised as a ‘communications crime’, so the name of victims can be shared easily without legal ramifications. ‘Victims need to be given the choice to remain anonymous, because they never got the choice on whether to release the photos,’ Zara told the BBC in November last year.

Research by the North Yorkshire Police and Crime Commissioner has shown that 76% of victims of revenge porn do not report their crime to the police, but 90% would if they were guaranteed anonymity. But as it stands, only 3% of revenge porn cases that are reported end in successful prosecution.

Typically, the offences are difficult to prosecute because the law around image-based sex abuse is so narrow and difficult to interpret. ‘We need a specific image-based sexual abuse law to get rid of the fragmented approach to dealing with these offences which is currently in place,’ MP Maria Miller, chairwoman of the Women and Equalities Select Committee said, ‘This patchwork law at the moment is difficult both for victims to understand and for police to implement.’

More than that, in not knowing what to do (or caring?) victims of revenge porn are often referred to charity helplines by police, rather than actually helping themselves and attempting to find a way to interpret current laws effectively. It’s with this in mind, that there are concerns about how useful a law against cyberflashing (sending unsolicited sexual images) would actually be in practice.

Even if the law were clear, that it was completely illegal, there seems to be many problems to consider. First, crimes against women are notoriously overlooked by police. If women suffering domestic abuse can’t have their cases taken seriously, how are the police going to respond to a woman upset about receiving a dick pic?

Secondly, technology makes sending unsolicited sexual images not only easier than ever, but more invisible than ever. It’s no coincidence that Snapchat very quickly became the home of the dick pic when it was evident that images sent disappear after a maximum of 10 seconds. Now, with the same feature available on Instagram, providing proof of an unsolicited image is extremely difficult.

Not only can messages be deleted, but it can also be made to look as though they were never sent, and while one would hope there’s technological advancements that could trace a message sent, with app owners so concerned about protecting users privacy and encrypting conversations, how easy would it be to prove that you ever received an image or message if it did disappear afterwards? We can screenshot, sure – but by the same token, with messages so easily unsent, how easy is it to prove that you never asked for it?

Women get victim-blamed all the time, our bodies can be violated in the most disgusting way and we will still be asked what we were wearing, how many sexual partners we’ve had and how much we had to drink. If this kind of abhorrent questioning is allowed during trials for crimes as serious as rape, how could we ever expect it not to be allowed in an offence of this nature?

The review is important, monumental even - especially for revenge porn and deepfake victims - and will hopefully mark a step forward in better protecting women from cyber sexual abuse, but whether or not the outcome of it will actually shift the culture enough for it to be practically useful is still up for debate.

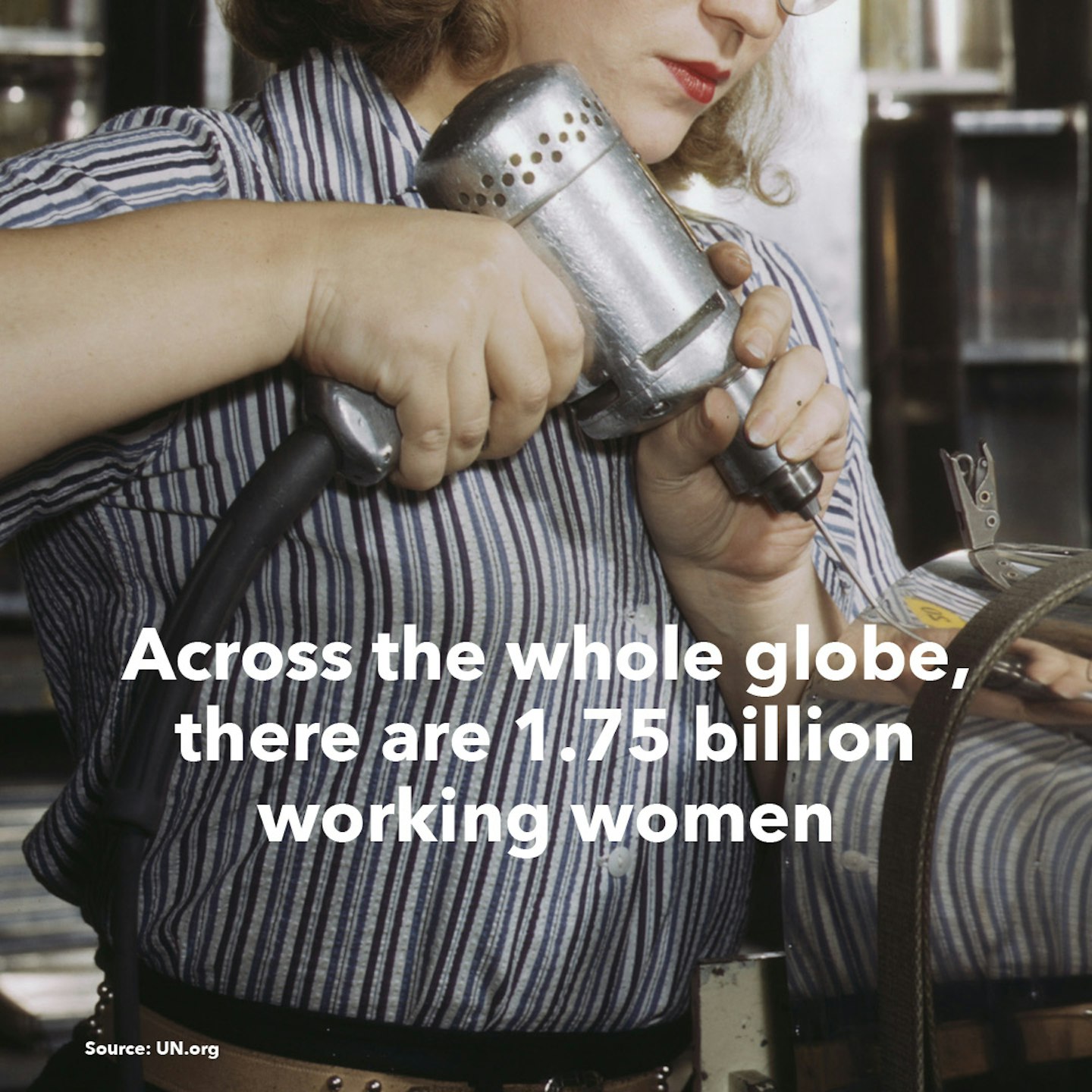

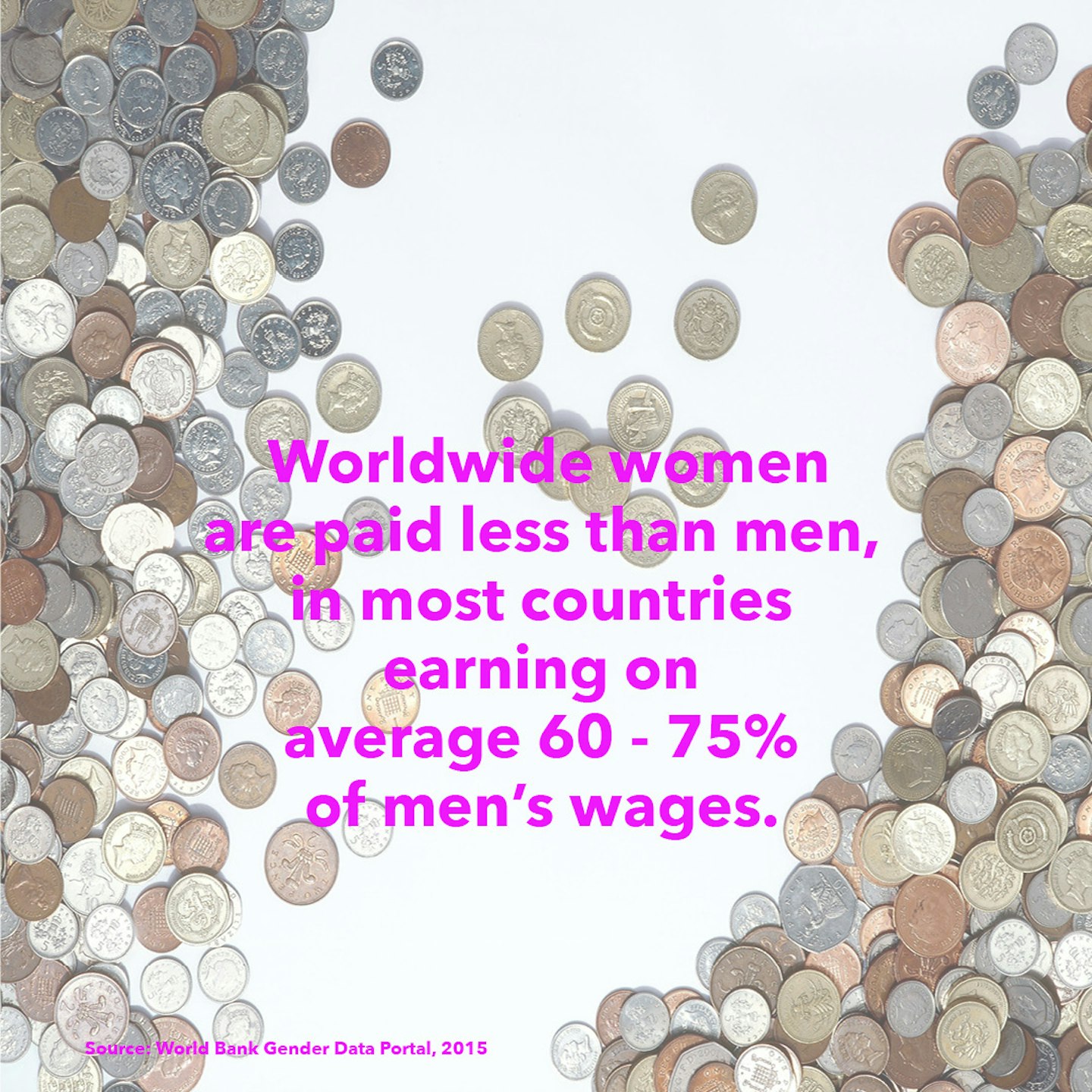

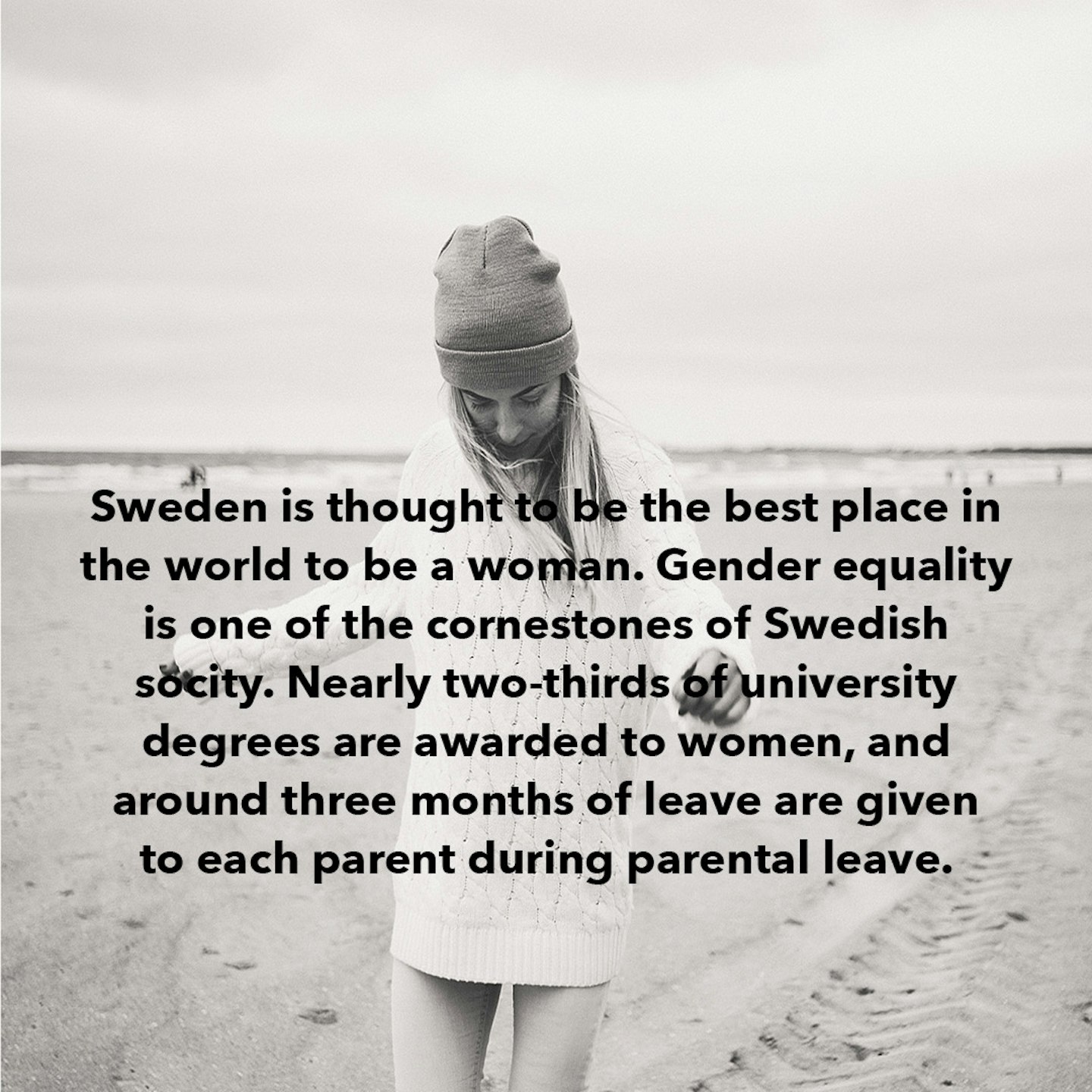

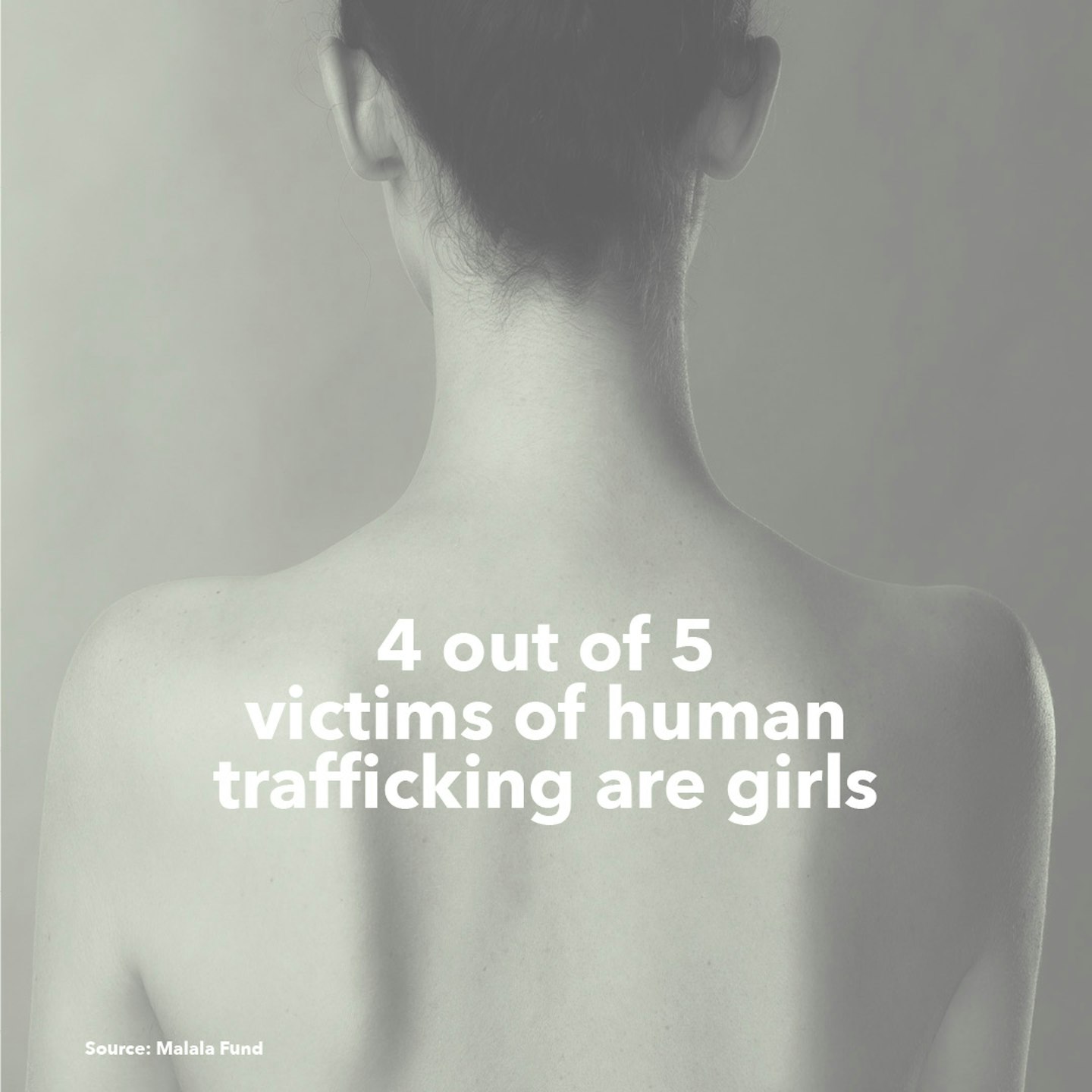

Read more: Sexism around the world in pictures...

Debrief Facts about women around the world

1 of 18

1 of 18Facts about women around the world

2 of 18

2 of 18Facts about women around the world

3 of 18

3 of 18Facts about women around the world

4 of 18

4 of 18Facts about women around the world

5 of 18

5 of 18Facts about women around the world

6 of 18

6 of 18Facts about women around the world

7 of 18

7 of 18Facts about women around the world

8 of 18

8 of 18Facts about women around the world

9 of 18

9 of 18Facts about women around the world

10 of 18

10 of 18Facts about women around the world

11 of 18

11 of 18Facts about women around the world

12 of 18

12 of 18Facts about women around the world

13 of 18

13 of 18Facts about women around the world

14 of 18

14 of 18Facts about women around the world

15 of 18

15 of 18Facts about women around the world

16 of 18

16 of 18Facts about women around the world

17 of 18

17 of 18Facts about women around the world

18 of 18

18 of 18