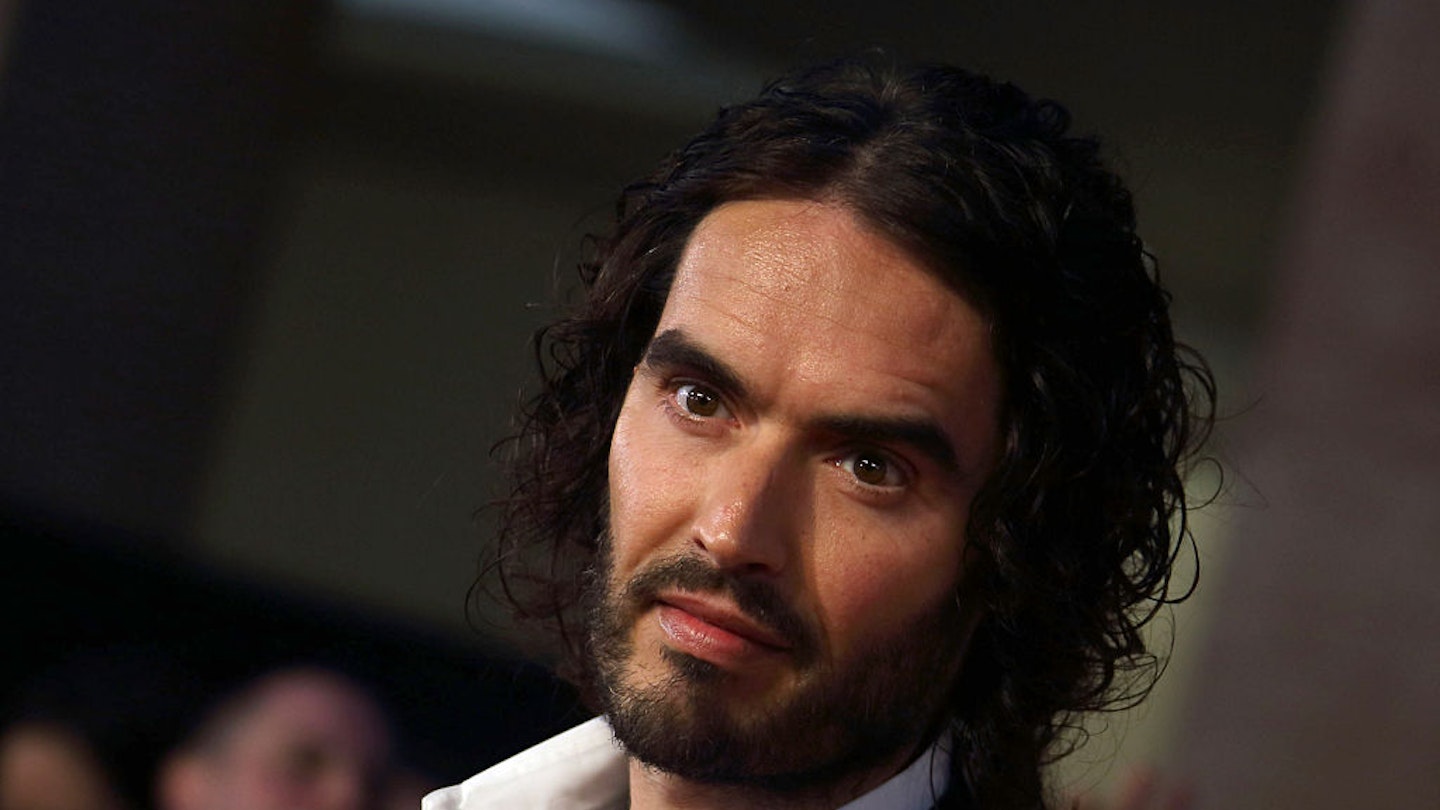

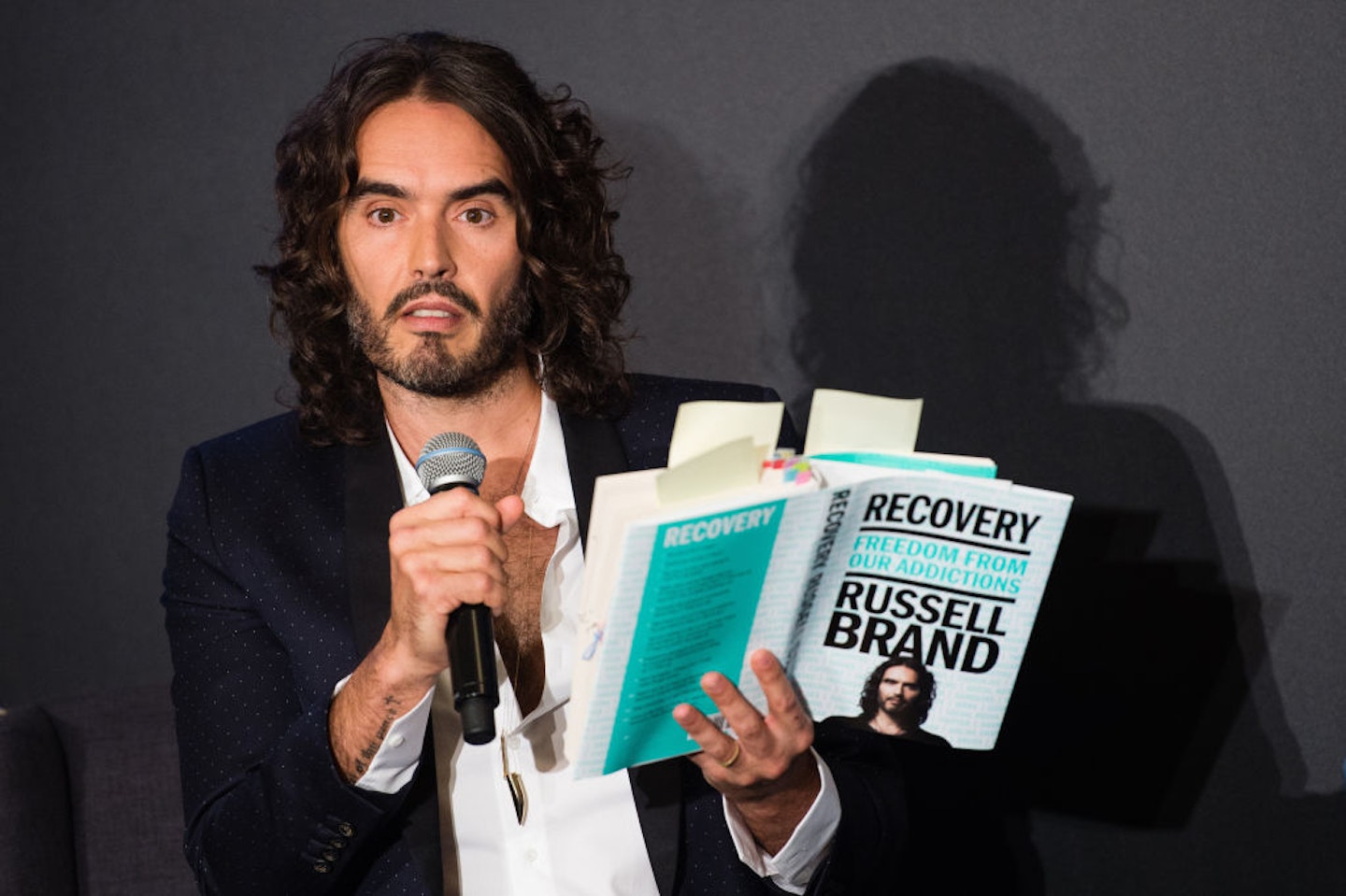

It’s been a hellish weekend full of overwhelming news and commentary surrounding Russell Brand. After whispers of an exposé incoming about an A-list British celebrity accused of sexual misconduct last week, the comedian outed himself on YouTube as the person facing ‘very serious criminal allegations’, allegations that he entirely denies. Then came the investigation published by The Sunday Times, in which four women accused him of crimes ranging from rape and sexual assault to emotional and physical abuse.

A Channel 4 Dispatches documentary aired around the same time, detailing the same accusations, spliced with videos of his comedy sets and interviews, exploring how the wider industry and culture of the time could allow such things to go unnoticed, or brushed over. Russell Brand denies all accusations against him, which are alleged to have taken place between 2006-2013. He says all of his relationships have been consensual, stating on YouTube, 'amidst this litany of astonishing, rather baroque attacks are some very serious allegations that I absolutely refute.'

It's perhaps unsurprising, given Brand’s pre-emptive YouTube video alleging that ‘mainstream media outlets are trying to construct […] what seems to me to be a coordinated attack’, that the response online has been extremely divided – many supporting the accusers, but many others also vehemently supporting Brand’s plea of innocence. Scroll through the online debate and you’ll notice one particular question being asked, over and over again: Why now?

‘The allegations are claimed to have taken place between 2006 and 2013, while Brand was presenter for BBC Radio 2 and Channel 4,’ one person tweeted. ‘Then why were they not reported to police at the time and why collectively only now come forward?’ Public figures appear to be asking the question too. Journalist Allison Pearson, who admitted she had not ‘read the full story’, tweeted ‘I just wonder why now?’ to hundreds of likes.

Before we explore that question, it’s important to understand exactly what Russell Brand is accused of. One woman accuses Brand of raping her without a condom against a wall in his Los Angeles home. She says she was treated at a rape crisis centre on the same day, which The Times says has been confirmed via medical records. Alleged text messages show that after leaving his house, the woman told Brand that she had been scared and felt taken advantage of, adding: ‘When a girl say[s] NO it means no’ to which Brand allegedly replied, saying he was ‘very sorry.’

A second woman alleges Brand sexually assaulted her once during a three-month relationship that she claims was ‘emotionally abusive and controlling’, occurring when she was just 16 and he 31. A third woman claims that he sexually assaulted her while she worked with him in Los Angeles, saying that he threatened to take legal action if she told anyone else about her allegation. A fourth also accused Brand of sexual assault, physical and emotional abuse.

Russell Brand denies all of the allegations.

It's worth noting one very important line from The Sunday Times investigation on the reason women have come forward now: ‘All said they felt ready to speak only after being approached by reporters. Several said they felt compelled to do so given Brand’s newfound prominence as an online wellness influencer, with millions of followers on YouTube and other sites.’

Now, we can’t speculate about why Brand’s accusers in particular chose not to go public with their allegations sooner. We can note that The Sunday Times investigators say one woman did report the crime to a Rape Crisis centre which alerted the Los Angeles police department, and that she is on record at the centre saying she ‘didn’t think my words would mean anything up against his’ and worried ‘her name will be dragged through the dirt.’ All of the accusers are said to have told people of their experiences at the time, which The Sunday Times says it has confirmed, and one is reported as saying Brand threatened her with legal action at the time.

What we can also do is explore more generally, outside of this specific case, the reason that sexual abuse allegations often do not surface for years. Because there are many reasons victims of sexual violence often do not go public, report the crime to the police, or even tell anyone at all. Put yourselves in the shoes of a victim of sexual violence, and maybe you’ll understand.

‘After I was raped, I was in denial for a long time,’ Julia*, 31, told Grazia. ‘I didn’t pretend it didn’t happen, but I sort of diminished it in my mind. I would tell myself “Oh maybe he didn’t hear me say 'No'”, "Maybe he didn’t feel me pushing him off", it’s like my brain was doing anything it could to protect me from feeling how deeply I’d been violated. It’s scary how quickly you begin to rationalise someone’s behaviour, because in that moment you don’t ever see it coming. You don’t think of someone as dangerous or out to get you, it’s almost like a fog of confusion, like “Wait, why isn’t he stopping?’. It took me a long time to accept that I was a victim of rape, that he’d meant to do that to me.’

For Julia, by the time she’d come to accept what had happened, she didn’t think she was able to report it. For the record, there is no time limit on when you can report to the police. So, even if it happened a long time ago, you can still go to the police if you want to.

‘I didn’t report because I didn’t think it would go anywhere,’ Emily*, 26, says. She was raped by someone she met on a night out in 2018. In England and Wales, more than 99% of rapes reported to police do not end in a conviction, according to the most recent government records from 2022.

I had seen the statistics about conviction rates, why should I put myself through that?

‘I knew it would be my word against his, and I had seen the statistics about conviction rates,’ Emily continues. ‘I thought about reporting, and then I imagined going to the police, retelling my story over and over again, having to convince them and however many other people that I wasn’t lying. Why should I have to put myself through that? It would’ve been so hard for my family too if it went to trial.’

Emily was also about to start a new job in another city when she was raped, and worried she would have to report it to her employer if she was forced to travel back and forth for an investigation.

‘People who haven’t experienced it won’t understand this, but pragmatically it’s like, ok how much of my time now do I have to give to this horrible thing that happened? How many times do I need to leave work to do what’s needed for a trial? I had been so excited about this new life I was starting and it was my dream job, I didn’t want this man to take anything more from me than he already had.’

Lydia McCartney, a trauma informed somatic psychotherapist at survivors' support network I Am Arla, explains that disassociation is a common experience for survivors of sexual abuse. 'It happens so effortlessly by the body when someone experiences sexual assault,' she says. 'The impact of trauma can result in a disconnect happening where individuals are able to compartmentalise or shut off their experiences as a form of protection. They cope, they survive, they achieve, they bury it and they "move on" because what’s the other alternative? When the body has been overwhelmed and safety, trust, autonomy shattered, people stay in this state for years and only when they feel somewhat ready can they seek the strength to speak up.'

What's clear from reading public commentary surrounding sexual violence is that common misconceptions about rape, and the many ways it can occur and impact people, contributes to the larger ignorance around why women don't always report right away. ‘People imagine a single violent act, a stranger in an alleyway or something, that you leaves you shaking and crying,’ explains Julia. ‘In that scenario it’s easy to imagine that a person would immediately break down and go to the police, but that’s not how rape always happens.

‘Yes, it is traumatising, and it stays with you forever, but it’s weird like, when you are immediately out of the situation and time is just carrying on like nothing happened, you feel a sense of wanting to do the same. It’s not like one day you’re fine with this great life and then suddenly, you’re just a rape victim with nothing to lose. Like anything bad that happens in life, you feel a need to just get on with things and not make what happened to you your entire world.’

Julia adds that this does not mean rape is something anyone should just 'get over', but that often you can bury emotions in an attempt to protect yourself. 'It is still a completely life-altering experience, but it's clear to me that this very extreme example of rape that people have in their minds, the stereotypical situation that's always on TV, that's what makes people so unable to understand women's real experiences and how easily it can happen, and why they then don't want to come forward. It is not always like the movies, and women still deserve to be taken seriously and find justice no matter what the circumstances were.'

When it comes to men who have considerable power, there’s also the legal battle of reporting. In a post Amber Heard vs Johnny Depp world, women not only have to fear an immense court case in which they are likely to be victim-blamed and have their character questioned, but they can even be sued themselves if the man is found not guilty - which statistics show he will be.

Then there’s the stigma of it all, the culture in which women are repeatedly not believed, that adds to the mounting pressure not to report when these crimes happen. ‘There are countless reasons why women and girls don’t report sexual violence, but one of the main reasons is our culture of disbelief, victim-blaming,’ Deniz Uğur, Deputy Director of the End Violence Against Women Coalition (EVAW) told Grazia. ‘The fear of not being believed is reinforced each time we see or hear victims being dismissed and sexual violence being minimised – whether it’s within our friendship groups, in the media or on social media.

It can take survivors years to process what happened to them and feel able to come forward.

Deniz Uğur, Deputy Director of the End Violence Against Women Coalition

‘Even when women do report to the police, they face a criminal justice system that is rife with rape myths and stereotypes and they are often not only failed by the system but harmed in the process,’ Uğur continued. ‘The vast majority of reported rapes don’t see charges brought, let alone a conviction and survivors from marginalised communities are particularly aware of the harm of police interactions and the criminal justice system. It can take survivors years to process what happened to them and feel able to come forward to the police. Healing from trauma is complex and not a linear process, and we need to see our justice agencies get better at understanding and responding to this.’

What is often denied to women when allegations are made pubic, is empathy. There is an unwillingness from commentators to put themselves in the shoes of the accuser, to ask how being sexually abused by someone you didn’t previously see as harmful might take an emotional toll that cannot be properly processed for years. One can understand why, if years after the fact a reporter came to you asking questions, noting that several other women were making similar accusations to you about a person, you might feel more willing to anonymously go on record.

‘I started to regret not reporting about three years after my rape,’ says Emily. ‘I do wish I’d been strong enough, if not for me but for other potential women he might’ve gone on to hurt. But then again, I don’t know how going through an investigation might’ve impacted me long-term. If he was let off, which statistics say he likely would be, would I have been traumatised further? Would he have felt justified in what he did? The worst possible outcome for me was reporting and the police dropping the case, because he would’ve felt vindicated and probably gone around telling everyone he was a victim of a false rape claim.’

The immediate response to historic rape allegations is often to question the timing, a reaction that only perpetuates a culture of disbelieving women. It's perhaps ironic then, that the very people asking the question 'Why now?', are the reason it can take so long for accusations to surface.

If you've been affected by sexual violence and want to talk to someone, visit rapecrisis.org.uk for support. The NHS offers

Sexual assault referral centres (SARCs) with medical, practical and emotional support to anyone who has been raped sexually assaulted or abused, which you can access here nhs.uk/live-well/sexual-health/help-after-rape-and-sexual-assault/ .You can also report rape at any time by calling 999, 101 or visit this website to report online: met.police.uk/ro/report/ocr/af/how-to-report-a-crime/

*names have been changed