Last year, the hurricane that was #MeToo movement was unrelenting in holding men to account for their workplace sexual harassment. Hopping from industry to industry, there was seemingly no safe place for women to go about their business without the threat of sexual harassment and abuse. One of the most unsurprising industries desolated by the gale force of women’s voices was the comedy industry.

Comedians are vulnerable in their jobs by nature. There is no HR system available for them and their pay packets depend on knowing the right booker who will take a chance on them until they gather a large enough following to become a household name. An industry like this is perfectly built to be taken advantage of by power figures, and as we know, powerful positions in any industry are almost always dominated by men. As a result, sexism and sexual harassment has been rife in comedy for many years.

The most notable example of this returned to the news this week, when 9 months after admitting to masturbating in front of several women without their consent, Louis CK was allowed to return to comedy. Performing a surprise, 15-minute stand up set at New York's Comedy Cellar, the admitted sex offender received a standing ovation from the audience. The think pieces ensued, had he paid his dues? Is 9 months not working a long enough punishment in the face of no legal charges?

As far as the public are aware, Louis CK has done absolutely nothing to ease the ongoing pain of his victims - who received death threats just for speaking out - other than release a (half-arsed) public apology once his offenses were made public. We could not possibly be able to tell whether or not he is still a sexual predator, and a safety risk for women, because there has been no formal rehabilitation, no legal punishment, just the loss of some employment for a man that was already worth $35million.

His reputation rightly went down the drain, but is losing your reputation rehabilitation for violating so many people? Is it enough that he now - allegedly, apparently - understands that it's not ok to masturbate in front of women without their consent? It's not enough to stop him from actually getting gigs, clearly, so how can we know it's enough to alter the deeply engrained misogyny that - in his mind - makes this behaviour permissible?

Louis CK isn't a one off either - last month it was announced that Netflix will resume working with Aziz Ansari - who was accused of sexual misconduct by a woman he once dated earlier this year. He's also resumed his stand up career with a routine about dating - although his own #MeToo moment is off the cards. Both these comeback attempts have led to the rise of the hashtag #MeTooSoon, which questions when - and if - we should put claims of sexual misconduct to one side.

When the allegations against Louis CK first came out, Vanessa Golembewski perfectly articulated the struggle women in comedy face. ‘In comedy specifically, it seems to be required for women to endure the male at his worst,’ she wrote for Refinery 29, ‘We’re expected to never be offended by or frightened of our peers who joke about rape. We’re expected to play along and prove that we can hang with the guys, to whatever extent they decide that means.’,

Click through to see the men accused of sexual harassment as part of the #MeToo movement

Debrief Men Accused Of Sexual Harassment

1 of 14

1 of 14Harvey Weinstein

2 of 14

2 of 14Ed Westwick

3 of 14

3 of 14Kevin Spacey

4 of 14

4 of 14John Lasseter

5 of 14

5 of 14Roy Price

6 of 14

6 of 14Nick Carter

7 of 14

7 of 14Michael Fallon

8 of 14

8 of 14Terry Richardson

9 of 14

9 of 14Steven Seagal

10 of 14

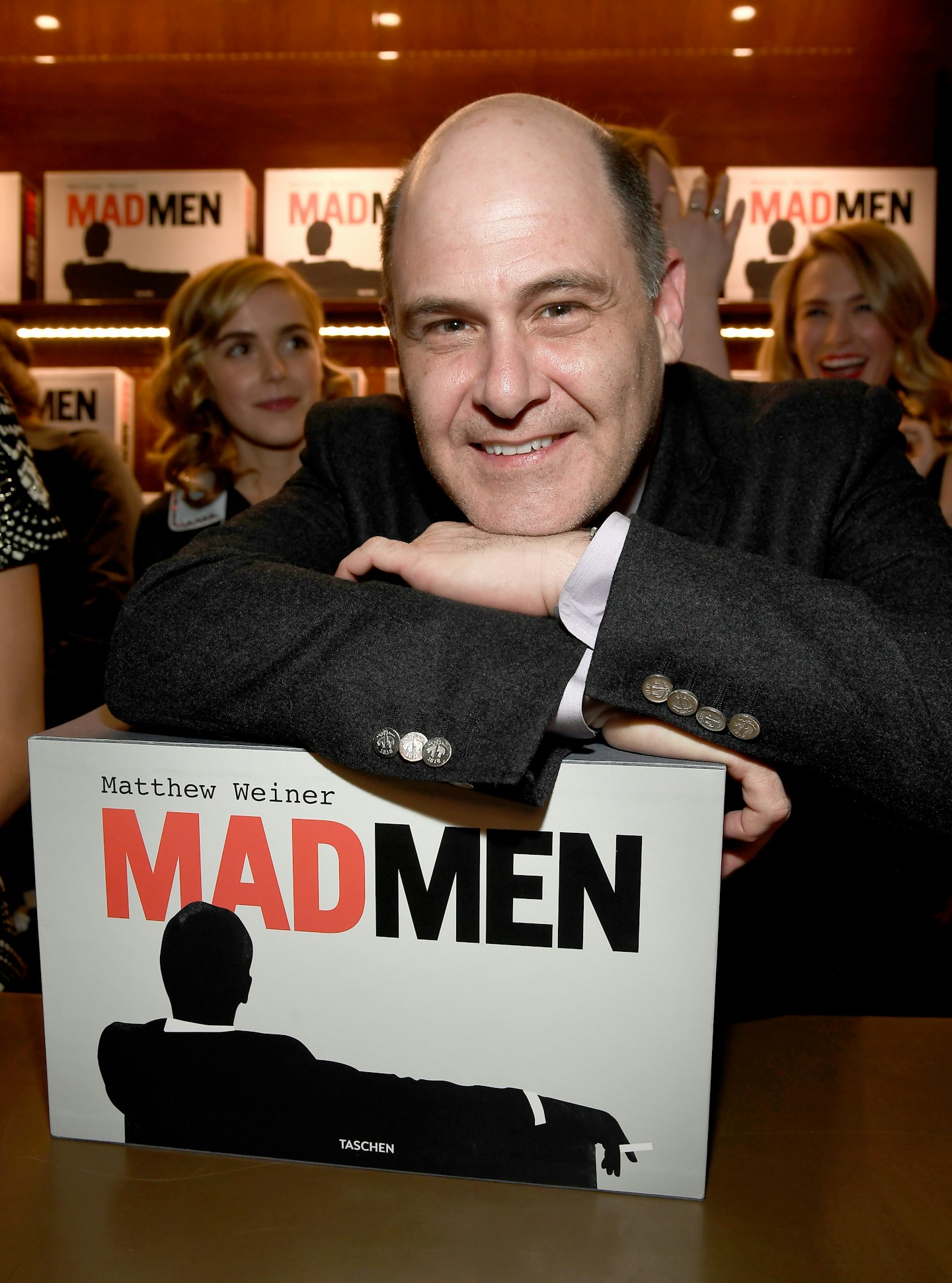

10 of 14Matthew Weiner

11 of 14

11 of 14Dustin Hoffman

12 of 14

12 of 14Jeremy Piven

13 of 14

13 of 14Louis C.K

14 of 14

14 of 14Ben Affleck

At this years Edinburgh Fringe, there where 29 #MeToo themed shows. The topic is clearly still on everyones minds, but are women better protected now than they were a year ago? As the worlds largest gathering of comedian, artists and performers, Edinburgh Fringe is the perfect space to try and understand this.

It has historically been a problem for women at the festival, according to author and publishing director of Stirling Publishing, Tabatha Stirling, who has attended the festival for over 10 years and hopes to perform next year. 'The Edinburgh festival is like any other event where darkness plus men and women plus booze plus excitement equals a platform ripe for both wanted & unwanted sexual behavior,' she says, 'historically at the festival, I’ve had my bum pinched, breasts fondled, unwanted attention and creepy guys who won’t quit, but to be fair this can and has happened anywhere.'

And according to comedy writer and producer Olivia Phipps, as the largest comedy festival, it is no surprise that Edinburgh is rife with 'inappropriate exchanges', whereby budding comedians in particular can be taken advantage of because their ability to book gigs rests on keeping certain gatekeepers 'sweet'.

'I would say the Fringe is probably the biggest culprit compared to other comedy festivals, but that is purely because of size,' she says, 'The relationship between performer and those above them is the risky one. Often these are men, often they have money, often they have a huge amount of influence.'

But almost one year post-#MeToo, whats changed? For Olivia, it's not that sex pests are being prevented from working, as one would hope, but that women are more confident in calling them out regardless.

'At the Fringe this year, pretty much everyone I met up with had someone they didn't want to bump into,' she says, 'I've been handed leaflets to shows by well-known sex pests. This year is the first year I've felt confident enough to call it out to the flyerer. Sometimes they looked relieved and it would open up a conversation:

"Fantastic stand-up in half an hour?"

"No thanks, he's a well-known sex pest."

"Oh God, I'm so glad someone said this. I really hate him, don't see this show. I just need the money and have no say which shows I flyer for.

As a performer at the festival, Amy Annette, creator and host of the popular panel show What Women Want, is very aware of the dangers facing female comedians, whose shows often finish late at night with no real security to help them get hope safely.

‘Edinburgh has been a traditionally safe festival, but obviously that doesn’t always withstand and I’m sure people have been attacked in the past,’ says Amy, ‘it has these amazing meadows in the middle [of the venues] but when people leave their gigs it’s really late, some finish at 1am, and there isn’t any formalised safety procedure for anyone.’

One would hope that practical measures would have been put in place post #MeToo to protect female comedians, and attendees in general. After all, with all of the #MeToo themed shows being showcased at the festival, its clearly something organisers are aware of and open to make money from. However, when we approached Edinburgh Fringe to find out what safety measures were in place for female performers, their statement showed little had actually been done to practically protect women. It read:

‘The Edinburgh Festival Fringe Society takes its role as guardian of the world’s greatest celebration of freedom of expression very seriously and, alongside many of our peers in the arts industry, we’ve taken a long hard look at how we can better support the people that make the festival happen each year.

‘We don’t pretend to have all the answers, but some of the measures we’ve taken include: bolstering the codes of conduct we have developed for venues and companies and our terms and conditions to give a clear indication that inappropriate behaviour will not be tolerated; creating a dedicated “know your rights” section on our website and distributing posters signposting to that information to every venue; and speaking to Police Scotland to shape our advice to participants.’

While improving your code of conduct and helping people understand their rights is useful, it doesn’t really offer any practical solutions to dealing with sexual harassment or misconduct. Setting up a reporting system, increasing numbers of security, creating safe spaces for women, these are suitable solutions. Putting up posters? Not so much. And in fact, these posters aren’t even very visible if Amy’s comments are anything to do by.

‘I have not seen those posters, I didn't know they had done that,’ she said, ‘I do know that some of the venues there have been stronger positions made for the staff that work for them so the bar staff or venue managers in terms of their safety but I haven’t had or heard of any sort of explicit move for performers apart from one led by the performers themselves.’

While the responsibility in making festivals safe should really fall on the festival organisers, the most notable protection for women has actually been provided by stand-up comedian Angela Barnes, who also performed there this year.

Creating the Home Safe Collective with a local taxi company, she started a donation scheme to ensure anyone identifying as a female or non-binary person could have a safe journey home following the murder of Eurydice Dixon earlier this year. Dixon was raped and killed by a random 19-year-old man on her way home from a gig in Melbourne. Angela’s decision to honour her and improve the safety of women in comedy was highly commended by other performers.

However, this burden shouldn’t have to fall on performers. In fact, Amy suggests there are simple solutions to helping people feel safe at the festival. ‘I think there are practical things like having security guards in the meadows, which is this long park people walk through to get to the flats on the other side,’ she said.

‘There is basically no centralised infrastructure, or support or HR responsibility for the thousands of people who come and each venue could be argued to have that responsibility [to protect people],’ she continued, ‘but Edinburgh as a festival is predicated on venues making money, industry making money but the performers not making any money. They come up here and spend £1000 deposit and then try and make that back by the end of the Fringe if they're in a paid venue, so it’s not entirely surprising that there hasn’t been a history of valuing them within that.’

The event is clearly a symptom of a much larger problem, in an industry where the workers are so vulnerable it makes sense that the largest festival at which they gather would amplify that vulnerability. However, as Amy says, there are practical things that can change in the industry as a whole. Sara Pascoe has been leading the charge to create an official trade organization that would protect workers from being exploited for years.

‘I really back Sara’s move to push comedians to join the equity union, who represent actors,’ she says, ‘[It’s] a place to flag bad experiences but also a place to arbitrate unpaid gigs because essentially unless you have a very powerful agent there isn’t much you can do.’

‘A lot of stuff with Me Too felt like people had said it and they weren’t listened to or they wanted to say it and didn’t know where to, so it took Ronan Farrow to open up a space and dialogue for it,’ she continued, ‘I don’t think we should have to wait for the media to be the arbitrator of these things and comedians are quite vulnerable to that grey scale space where there’s no one for you to officially talk to so something that has international recognition would be great.’

In the meantime, it seems like those who wield power within the comedy industry, from bookers to festival organisers, could still do a lot more to protect women from sexism and sexual harassment. These solutions are not difficult, it takes a few conversations with the people who are impacted to understand there are tons of small, practical ways you can make a space feel safer. We can only hope that at next year’s Fringe, and at the next comedy show you attend, these conversations have finally been had- and that Louis CK doesn't randomly appear for a 15-minute surprise set...

If you want to know more about Amy Annette'sWhat Women Wantclick here