Today, the government published the long-awaited review into the decline of rape prosecutions in England and Wales, with ministers apologising to survivors failed by the justice system under the governments watch.

The lord chancellor, Robert Buckland QC MP, told reporters he was ‘deeply sorry’ that so many victims of sexual violence did not see their perpetrators brought to justice, with the report including a foreword that stated ministers were ashamed of the findings.

‘In the last five years, there has been a significant decline in the number of charges and prosecutions for rape cases and, as a result, fewer convictions,’ it read. ‘The vast majority of victims do not see the crime against them charged and reach a court: one in two victims withdraw from rape investigations. These are trends of which we are deeply ashamed. Victims of rape are being failed. Thousands of victims have gone without justice. But this isn’t just about numbers – every instance involves a real person who has suffered a truly terrible crime.’

The government has long been warned that rape is effectively ‘decriminalised’ in England and Wales, with conviction rates falling to record lows year on year. Last year, the new victims commissioner, Dame Vera Baird QC, published her first annual report stating: ‘In effect, what we are witnessing is the decriminalisation of rape. In doing so, we are failing to give justice to thousands of complainants.

‘In some cases, we are enabling persistent predatory sex offenders to go on to reoffend in the knowledge that they are highly unlikely to be held to account. This is likely to mean we are creating more victims as a result of our failure to act.’

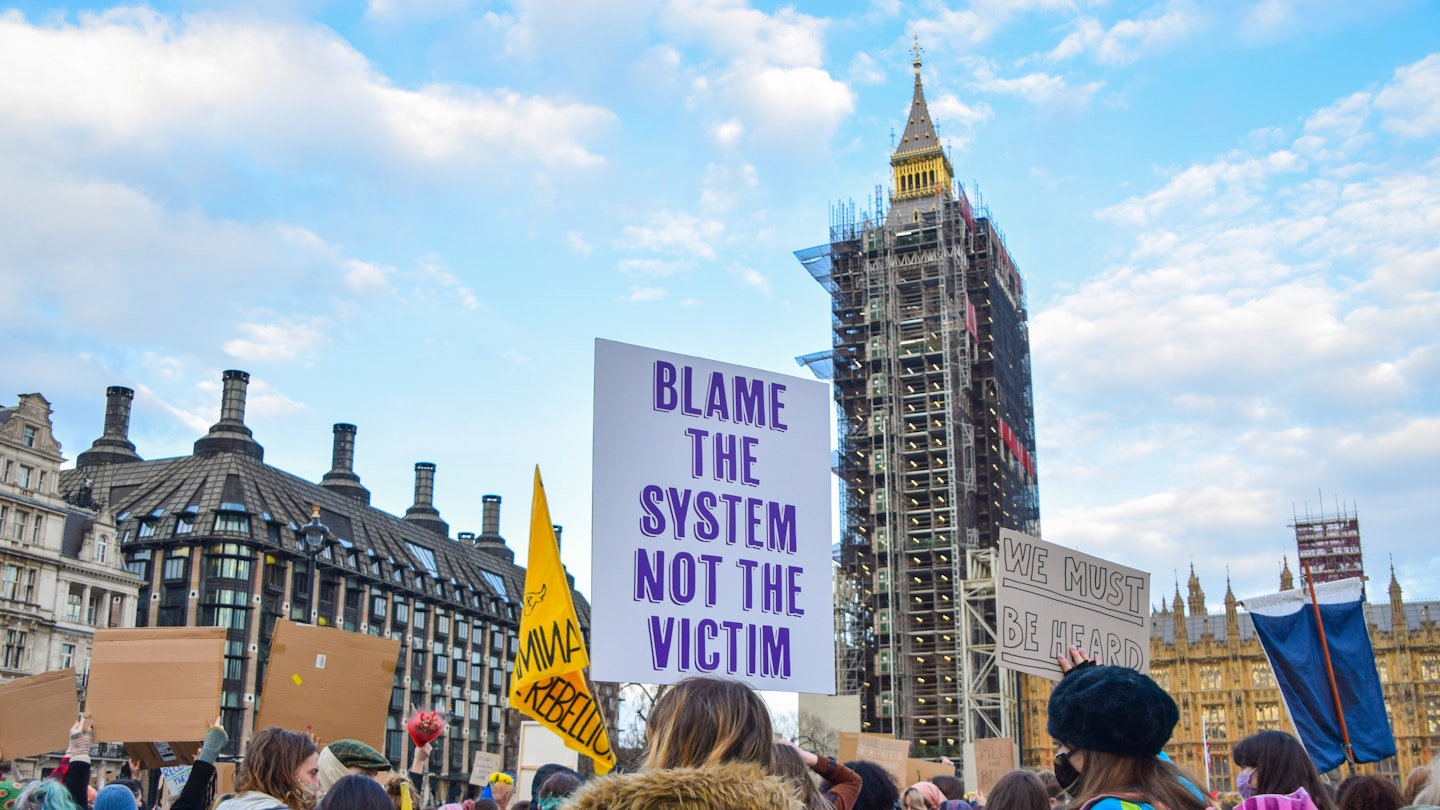

Apologies then, while meaningful to some, feel far removed from what survivors really need right now. In fact, the best apology for victims of sexual violence would be a review that actually went far enough to prevent sexual violence and tackle the root causes.

According to the leading organisations in tackling violence against women and girls (VAWG), that’s exactly what the review hasn’t done.

‘To truly realise a step-change for all rape survivors seeking justice, the Review would need to include more far-reaching recommendations examining who is dropping out of the system and why, or the barriers to justice which mean women with intersecting identities don’t report in the first place,’ Andrea Simon, director of the End Violence Against Women Coalition (EVAW) said in a statement. ‘Without a meaningful equalities analysis, we run the risk of continuing the two-tier approach to justice currently in place.’

The rape review promises to increase prosecution rates before the end of this parliament – which may be years away – and roll out a pilot scheme called Operation Soteria which will push police and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) to focus investigations on suspects rather than complainants' credibility. The government says there will be ‘scorecards’ to measure ‘timeliness, quality and victim engagement’ plus ‘implementation of the action plan’, published every six months. The review does not specify who will be responsible for scoring. According to Simon, it does not go nearly far enough in putting complainants first.

‘The collapse in rape prosecution rates clearly point to failings in a justice system that does not put survivors first,’ she says. ‘Yet the Review contains little that would hold criminal justice agencies to account. We would have hoped to have seen some measures examining the governance of the CPS and mechanisms that would demand greater leadership and prioritisation of rape justice among senior leaders of the police, CPS and Government.

We need a ban on the use of sexual history evidence and an honest look at the role of juries.

‘We also needed more in-depth interrogation into what is going wrong in courts,’ she continues. ‘Including a ban on the use of sexual history evidence and an honest look at the role of juries, and the re-traumatising impact of the courtroom.’

While the review does propose to extend the pilot scheme that would allow victims to pre-record evidence and cross-examination – to spare them the trauma of attending court – it says it will only be rolled out nationally if proven successful, measures of which are not detailed.

The review also touches on the issue of ‘digital strip searches’, where some complainants were left without their phones for months and saw their entire communications dissected, with ministers proposing that ‘no victim will be left without a phone for more than 24 hours, in any circumstances’ and ‘any digital material requested from victims is strictly limited to what is necessary and proportionate to allow reasonable lines of inquiry into the alleged offence.’

The police and CPS have come under fire previously for ‘digital strip searches’ when complainants were made to sign ‘digital data extraction consent forms’ that, according to the Centre for Women’s Justice, saw police gather ‘unlawful, discriminatory and intrusive’ data. They won their legal challenge last year, resulting in changes to the way police are able to gather data on complainants.

Other proposes in the rape review have also come from prior backlash over the years, including the fact that complainants were previously not allowed to seek therapeutic or clinical support while their case was being investigated, or when they were offered support were told not to discuss details of the alleged crime. Now, the rape review proposes victims will the right to access to therapeutic support, ‘such as an Independent Sexual Violence Advisor (ISVA) where appropriate’.

In more proposals that arguably represent the bare minimum, ministers promise victims will now receive ‘receive clear, prompt communication throughout the process’ and better information about their rights.

For the leading women’s organisations that feel disappointed by the report – including EVAW, Imkaan, Rape Crisis England and Wales and Centre for Women’s Justice – the fundamental problem is that none of the proposals show a real effort to listen to survivors about what’s needed for real, radical change in protecting women from sexual violence.

‘We have criticised the Review for not meaningfully engaging with survivors throughout its two years and unfortunately these recommendations reflect this failure to hear from survivors themselves,’ Simon concluded. ‘To rebuild the public confidence that has been so deeply damaged by the collapse in rape prosecutions, we urgently need to start seeing improvements, and investments in levelling up across the whole justice system to deliver the justice all rape victims and survivors deserve.’

Read More:

The Police And CPS Are No Longer Allowed To Ask Sexual Abuse Victims For Their Mobile Phone Data