We know smear tests save lives - 5,000 a year in the UK to be exact - yet, there is to a distinct disconnect between receiving and getting an appointment. Like any NHS service, the appointment times are limited and the decision lies with the recipient whether a Wednesday slot at 3.15pm or a 16-week wait is more convenient. Whether you’re chained to your desk or a freelancer for whom every hour is a billable opportunity, the options are never attractive. Do you tell your (likely male) boss you have to cancel that meeting because you need to have some cells from cervix checked, or put off a potentially life-saving test for at least another four months? It’s a choice you shouldn’t really face, but in fact, many women do.

According to Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust, there has been a 52% reduction in screening samples taken through sexual health services in England. Why? Women are struggling to access the test. Not only are sexual health services declining, but they’re declining in a climate of overstretched and overburdened GPs. A quarter of women are only offered appointments during 9-5, with one in 10 states they don’t want to delay attending but don’t have a choice because they can’t book a more suitable time.

‘We’re getting more and more women coming to us saying “I can’t get an appointment at my GP”, “I can’t attend my sexual health service”, or “there’s a 16-week waiting list”’, says Kate Sanger, Head of Communications and Public Affairs at Jo’s Trust, ‘more and more women are coming to us with these kinds of complaints.’

It’s not surprising then, that there has been such a dramatic reduction in samples taken, with an inflexible screening system surrounding a test that already has so much stigma attached to it. ‘We already know women are having to overcome all of these different psychological barriers to even pick up that phone,’ Kate continues, ‘to then be told “oh there are no appointments” or “you’re going to have to wait 10 weeks” then the chance of them going for the test is much more reduced.’

While it shouldn’t justify not going for your test, making it more difficult for women to attend is likely, for some, encouraging them to put it off indefinitely. Though it’s not just embarrassment that causes women to delay the test, which it does for 35% of us, it can also be extremely uncomfortable for women who have experienced sexual violence, which one in five of us have (and even this is a calculation based merely on the number reported).

The psychological barriers can’t be dismissed. For many, it’s awkward and embarrassing to have their vulvas and bodies felt. If you’re physically disabled, house-bound, experiencing mental health issues, like anxiety or depression, enduring the lifelong battle of dealing with sexual violence, how likely are you to attend a test that will already push you out of your comfort zone if your GP has a 16-week waiting list?

That’s why Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust is campaigning for the introduction of self-sample tests, to not only tackle the increasingly inflexible appointment system but the invasiveness of the test itself. Self-sampling involves inserting a ‘self-collector device’ into the vagina, which is thinner than a speculum and shaped like a tampon, then with the click of a button the device collects fluid from your vagina and once removed, you deposit that fluid into a test tube to be sent off to a lab.

Not only does the self-sample test allow women to feel more at ease taking it, but it tests HPV first, as opposed to simply testing for abnormal cells. Currently available on the private market, the test is yet to be introduced on the NHS, and with 64% of Grazia readers saying they would prefer a self-sample test than the speculum-based one, it’s set to revolutionise cervical cancer screenings.

This comes alongside changes in the entire testing system, which will now be HPV primary tests, as the self-sample kits are. Formerly, the smear test would check whether your cervix contained abnormal cells, then if your result was positive you would be sent on to be tested for HPV 16 or 18, which cause 70% of cervical cancers. However, many women have abnormal cells, and since our cells are constantly changing, they can often return to normal within months.

‘We’re really excited about HPV primary screening,’ Kate tells Grazia, ‘but again we have concerns about it coming into a programme that isn't accessible, that doesn't have a good IT system and where attendance is dropping.’

That’s why self-sampling is so important, but also why the screening system needs a complete modernisation. ‘Being able to book appointments online or using an app is important’, Kate continues ‘where it’s not all dependent on a letter being sent out and those more old-school methods.’

And that’s not the only recommendation, Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust also found women want mobile screening clinics, similar to the breast cancer clinics, where you can easily be tested somewhere other than your registered GP. Not only would it encourage women not to put off the test, it would give them greater access when struggling to make appointments around professional commitments.

While women not attending appointments due to work is an understandable excuse, it’s not excusable on the part of the employer. This is why Jo’s Trust is also pushing for employers to join their Time to Test campaign, where they pledge to raise awareness of screenings in the workplace. Essentially, employers commit to making sure they’re employees can attend a screening, whether that’s by offering flexible working hours or working from home.

In an increasingly inflexible work culture that continues to overburden women, it’s a vital campaign. And since we’re finally at a point where when women’s health is peaking researchers interest, it’s integral we too treat it as a priority. That means ensuring all women have access to the test, and when they do, actually go for it.

If you want to know more about cervical cancer screenings, visit Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust here.

This isn't the only area of women's health that needs more research and revolution...

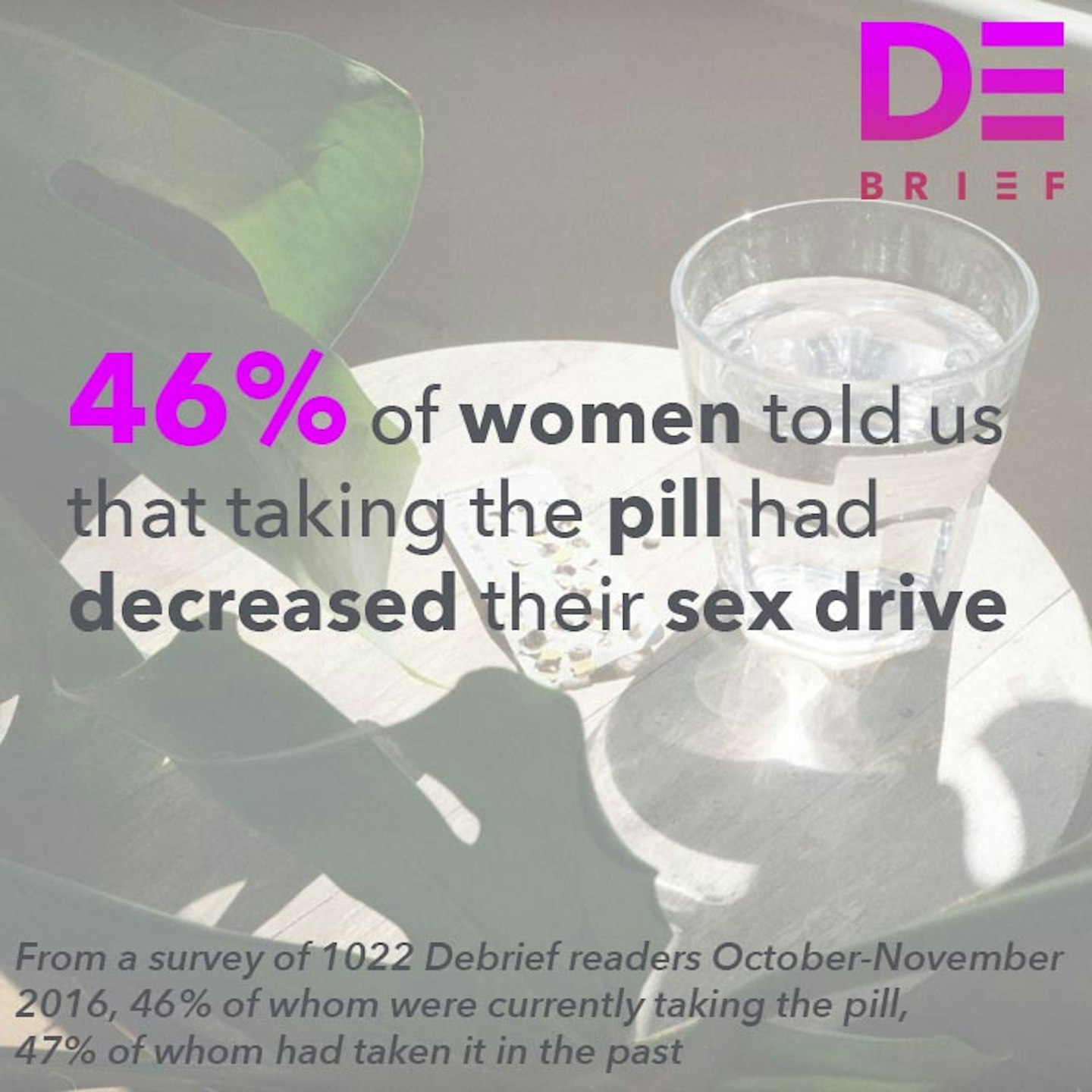

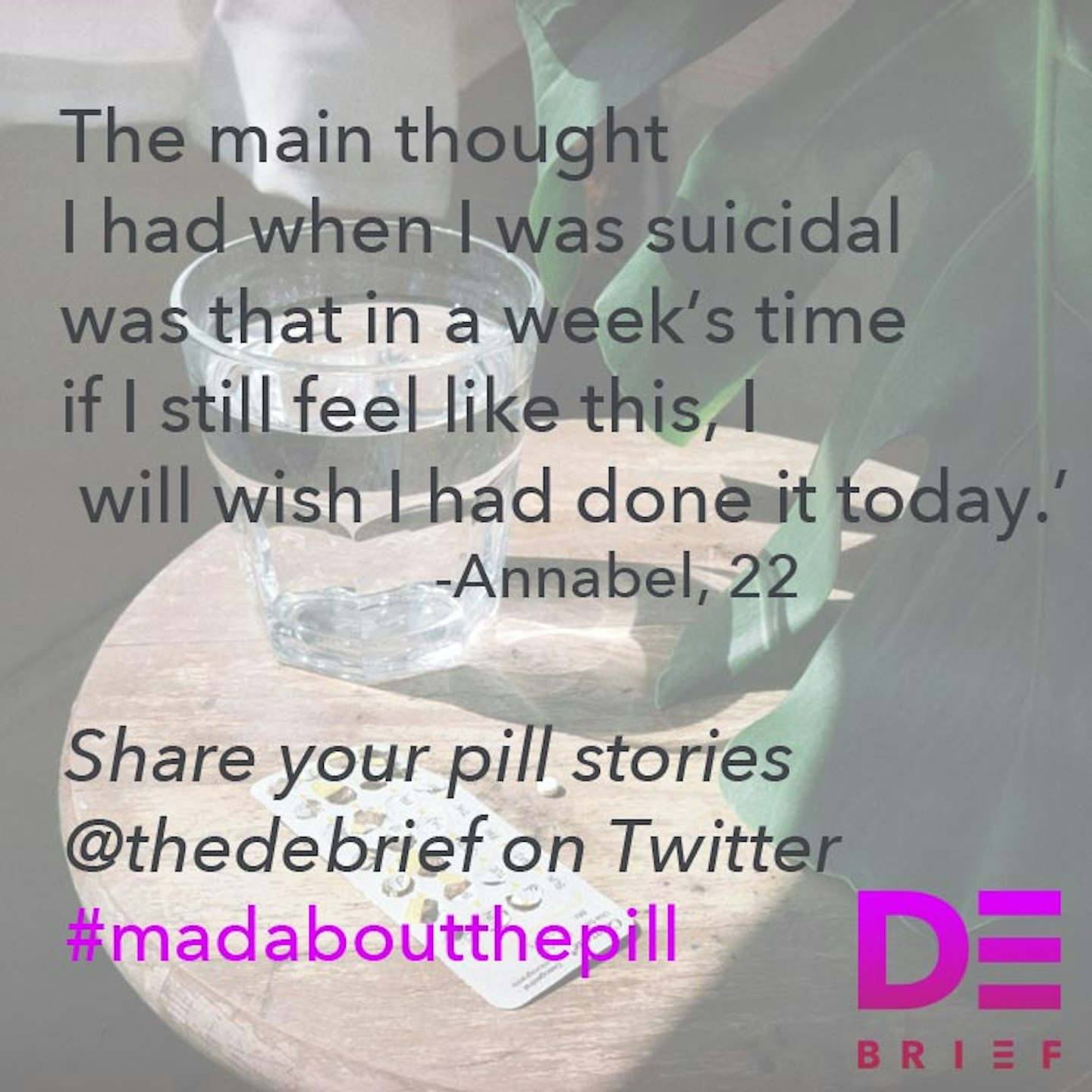

Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

1 of 9

1 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

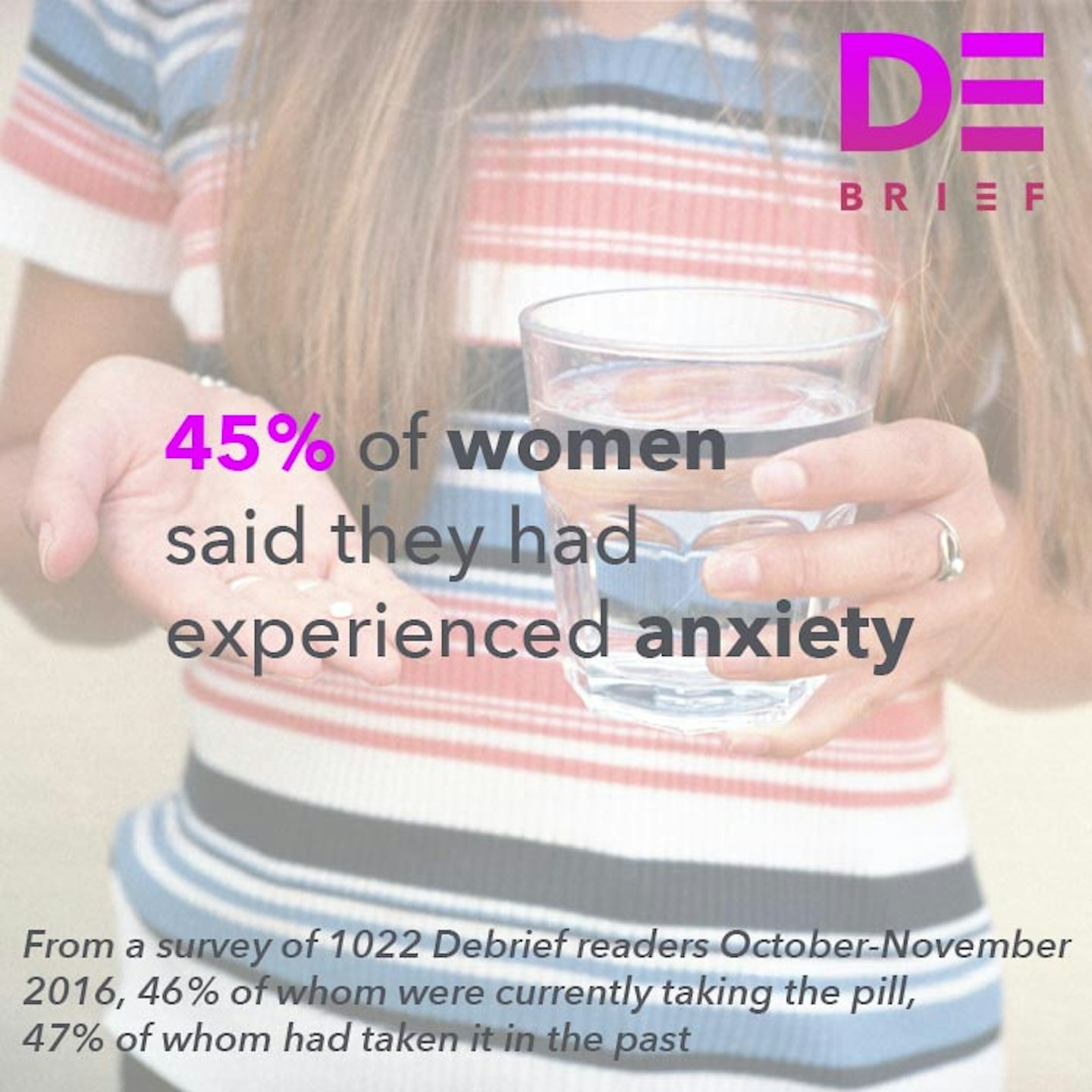

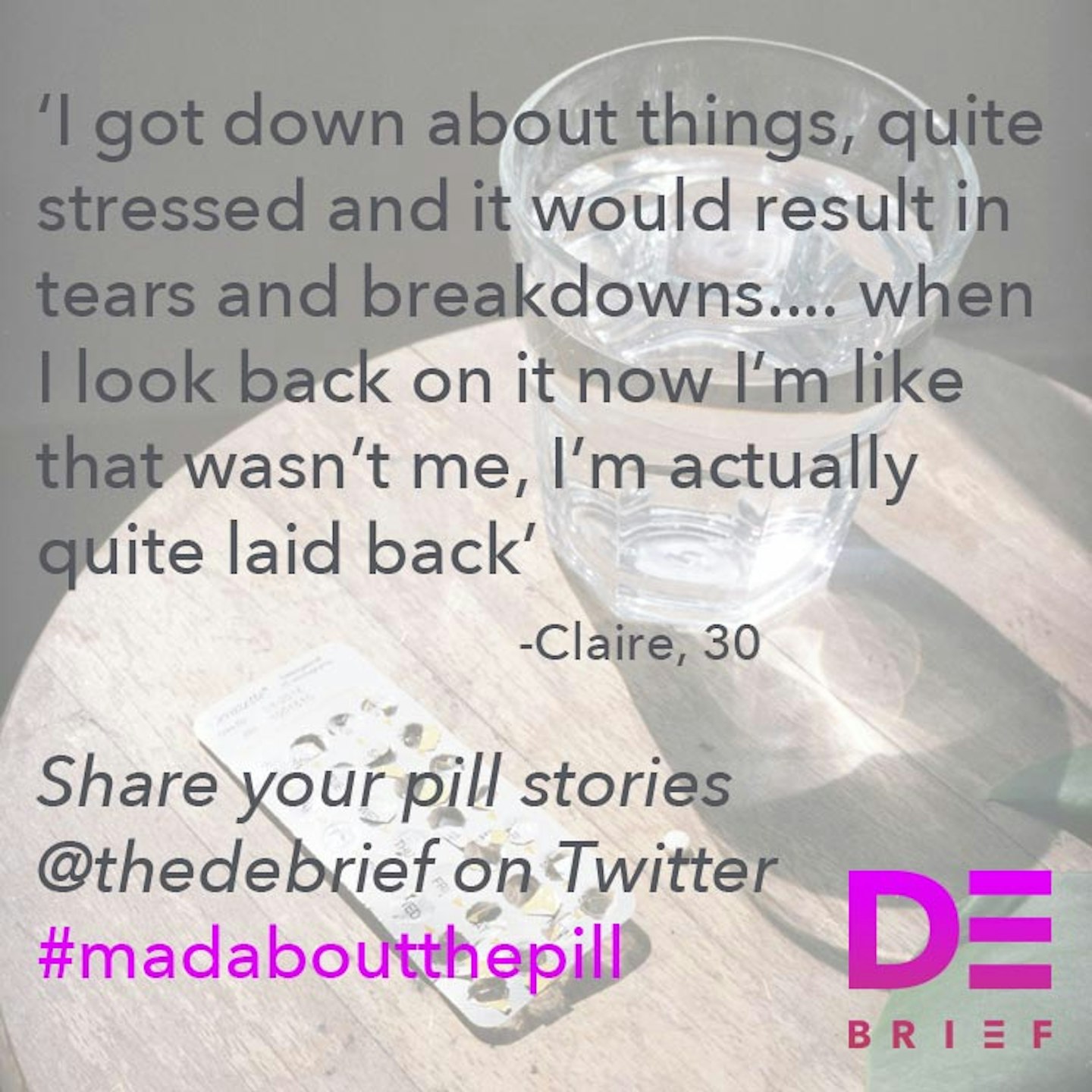

2 of 9

2 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

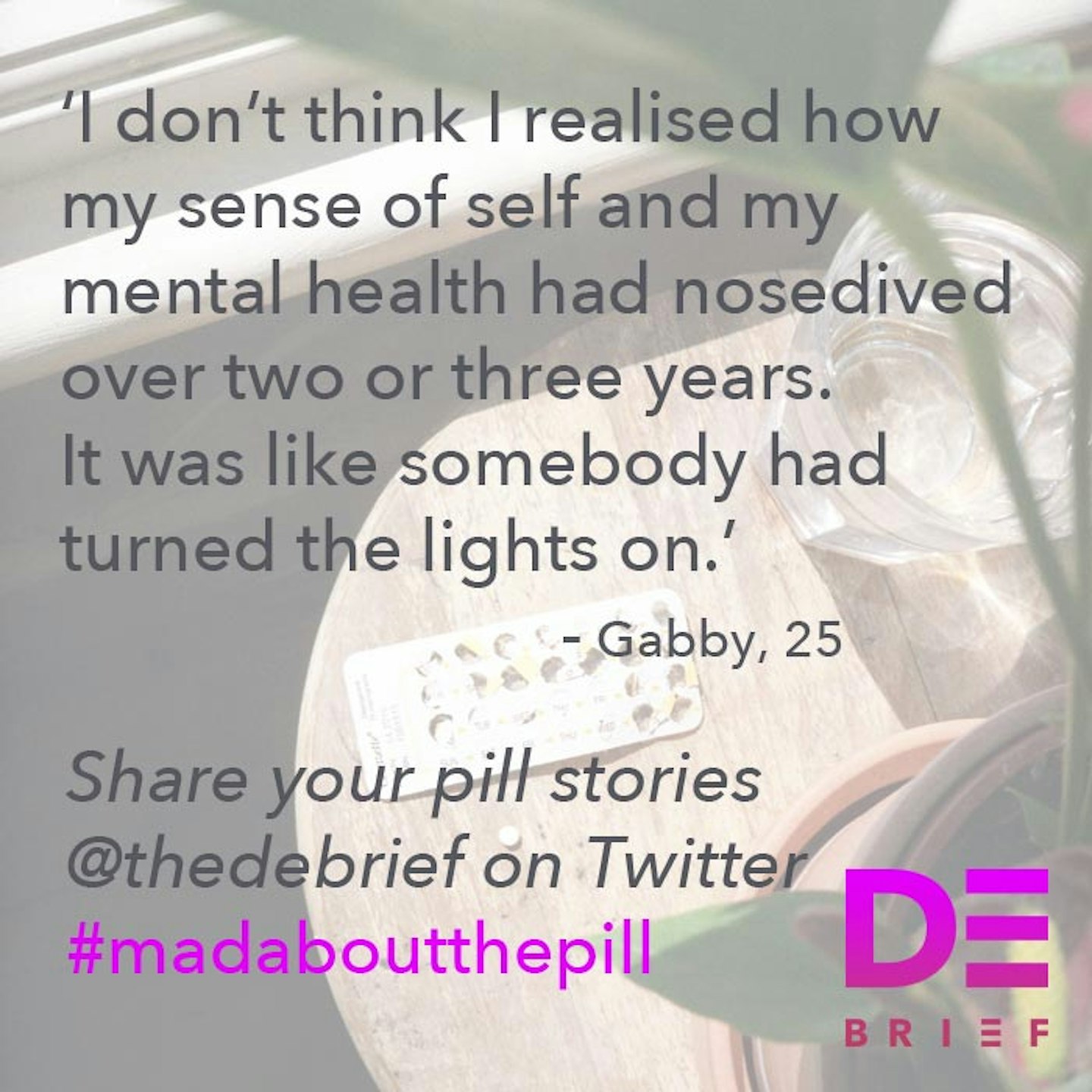

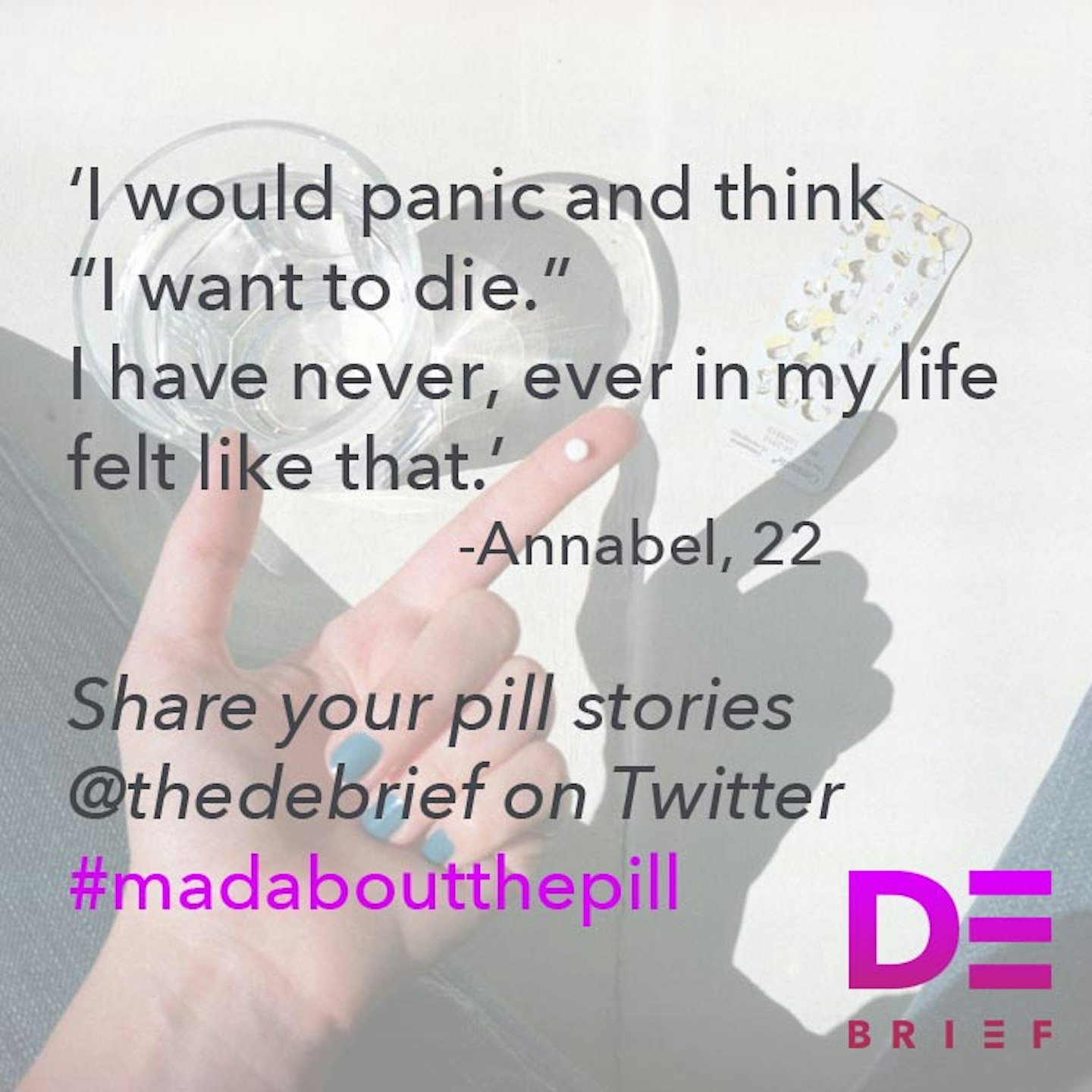

3 of 9

3 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

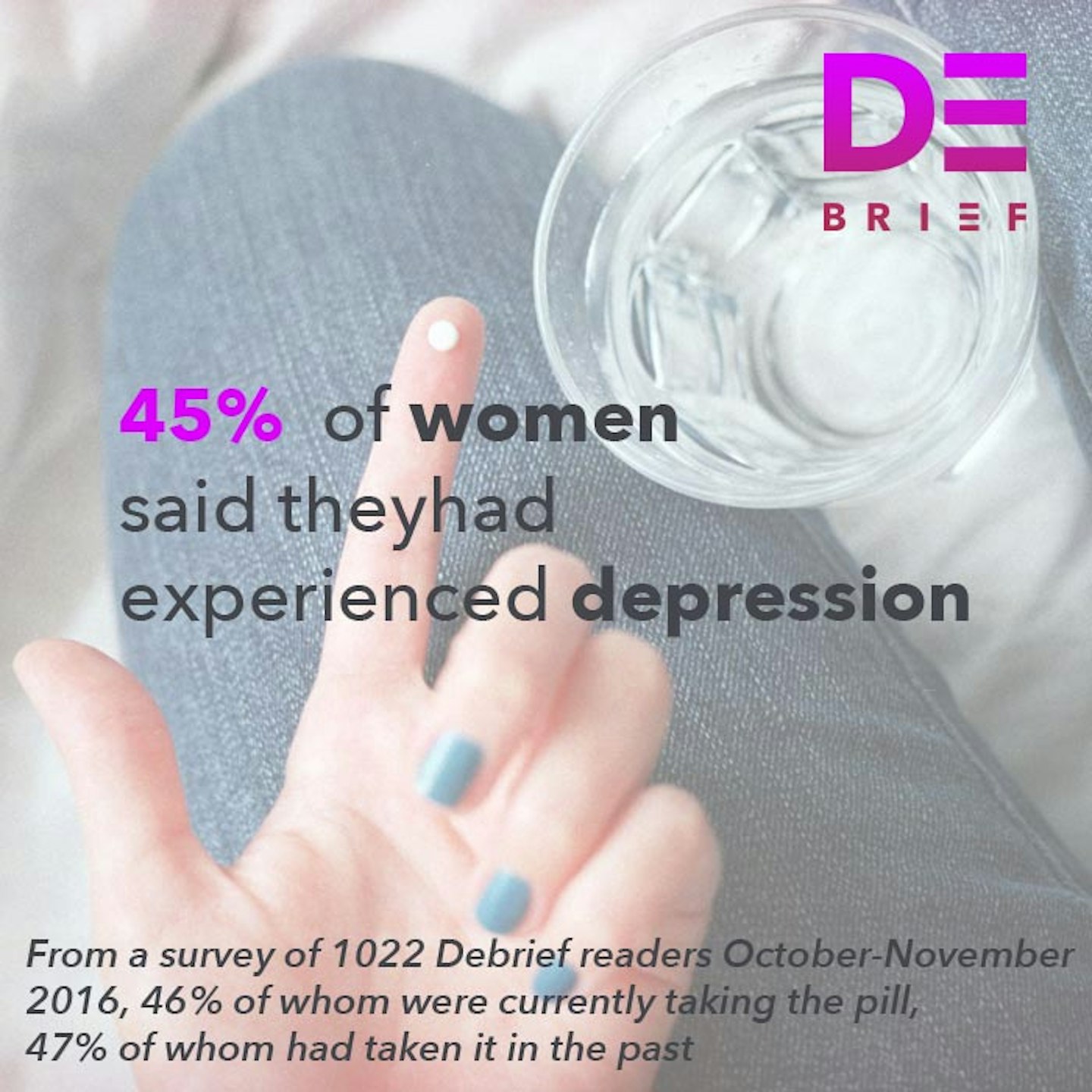

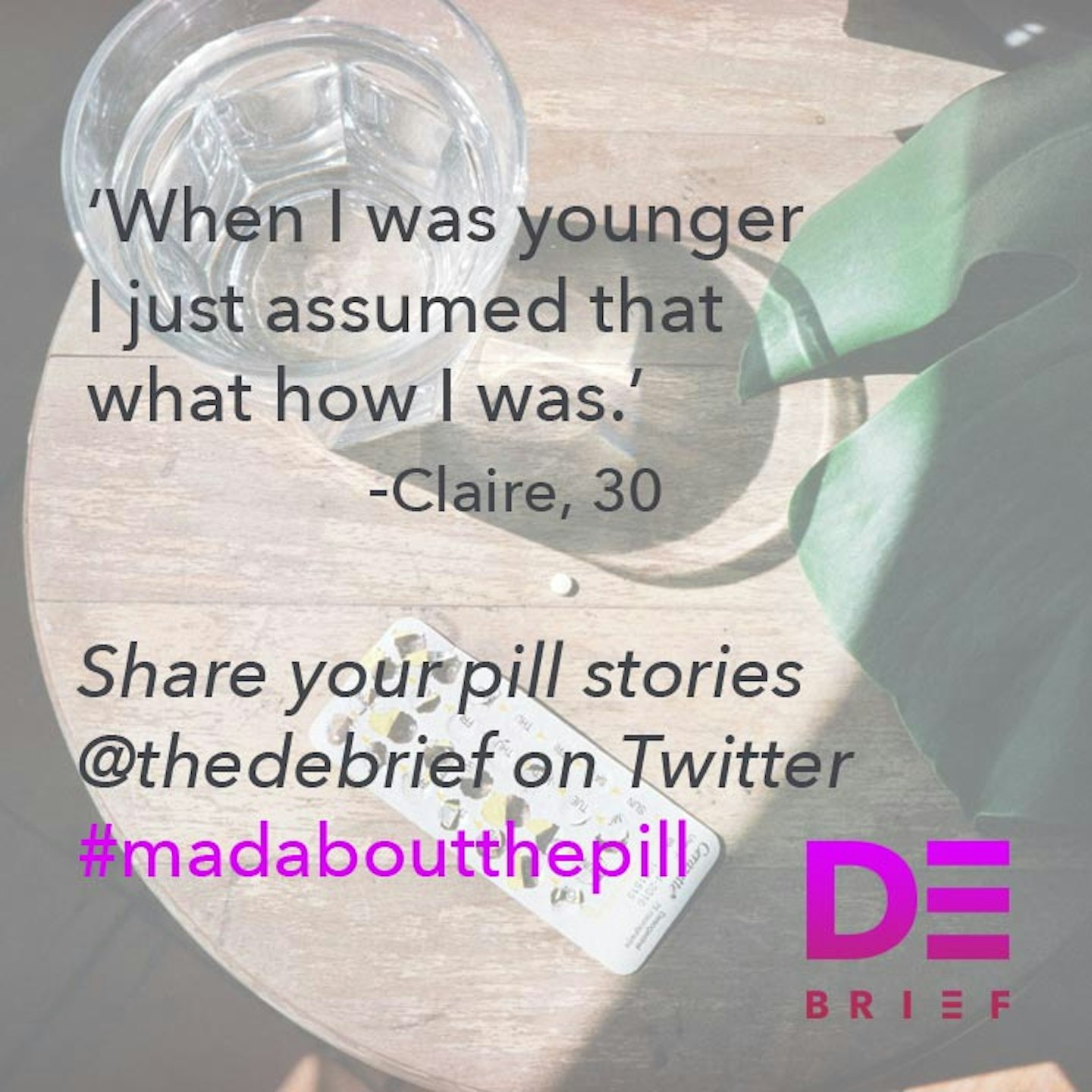

4 of 9

4 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

5 of 9

5 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

6 of 9

6 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

7 of 9

7 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

8 of 9

8 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

9 of 9

9 of 9