In 2020, in response to the protests for Black Lives Matter, the fashion industry had to face its own reckoning. As brands began to address issues of inclusivity and diversity, a groundswell of organisations sprung up, all of which share a common goal: to promote the interests of Black talent. While this was overwhelmingly positive, it also showed how little has fundamentally changed since the ‘50s. In 1949, the National Association of Fashion And Accessory Designers (NAFAD) was founded in America, with the express purpose of promoting equal opportunities for Black fashion designers, aiming to ensure that the same doors were open to them as their white peers. One extra thing we can do as consumers, as well as supporting Black-owned businesses, is to recognise the Black designers who have shaped fashion history – and to remember their stories.

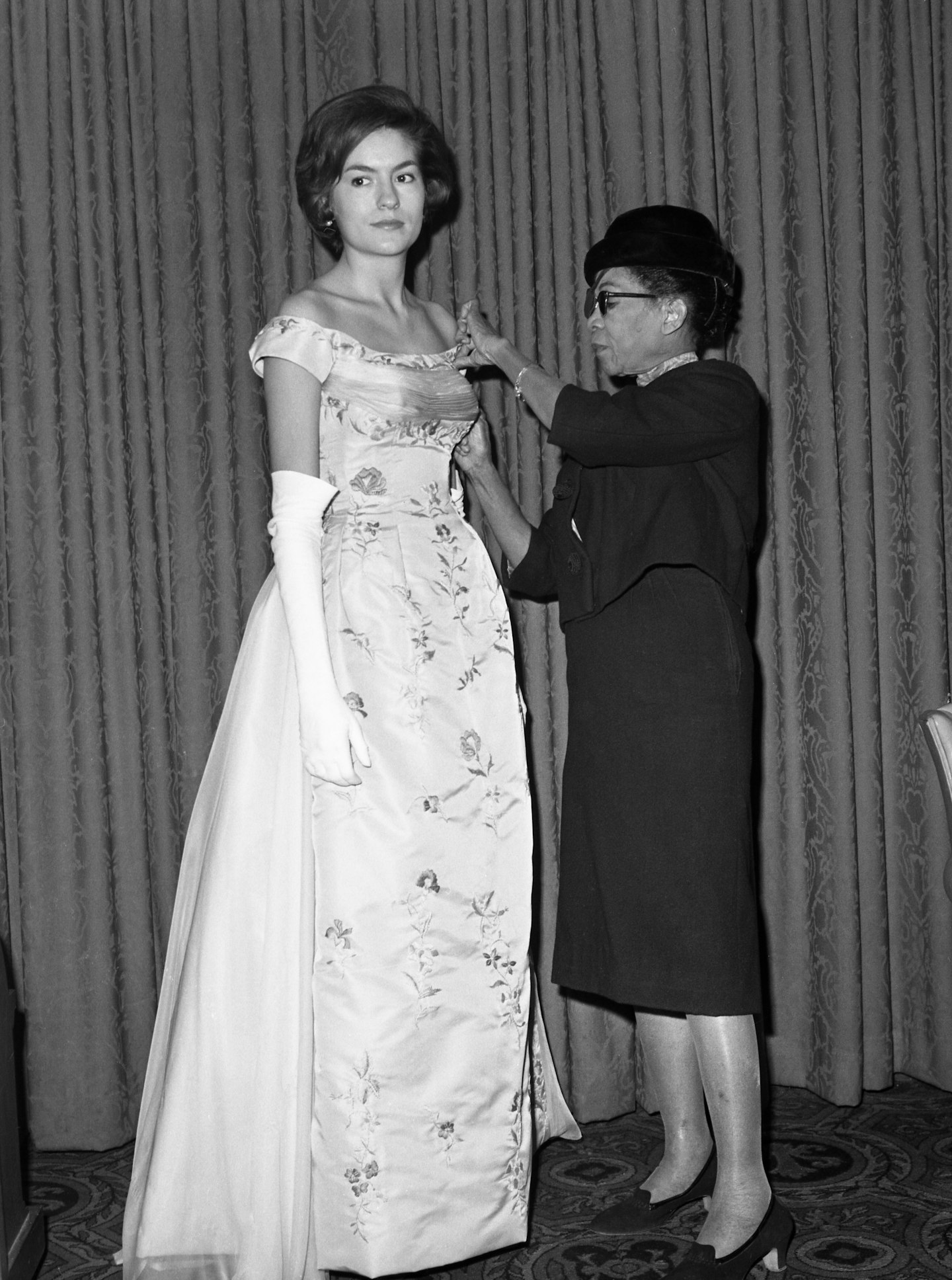

Zelda Wynn Valdes

Zelda Wynn Valdes (1905 - 2001) was born in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, in an era when segregation was a part-and-parcel of daily life. According to her obituary in The New York Times, written posthumously as part of a series called ‘Overlooked’, marking the Black men and women whose deaths had not been reported on when they originally occurred, she started out as a storeroom worker in a boutique, eventually climbing the rungs to seamstress. At the height of her career, Valdes was designing clothes for Ella Fitzgerald and Maria Cole, Nat King Cole’s wife, for whom she designed her glorious off-the-shoulder wedding dress in 1948, opening her own boutique the very same year. Although the exact history is contested, it’s also believed that she worked for Playboy, producing around 35 of the famous bunny costumes for Hugh Hefner.

Ruby Bailey

Like Zelda Wynn Valdes, Ruby Bailey (1905 - 2003) was part of the National Association of Fashion and Accessory Designers (NAFAD), an organisation that was founded in 1949 to promote and support Black design talent in the fashion industry. Bailey designed costumes and clothes that majored in print, colour and embellishment, and, according to the Museum of the City of New York’s blog, was an important fixture in Harlem’s social and arts scene. Unravel, the fashion and culture podcast, has an episode dedicated to her life and work.

Ann Lowe

Creating one of the most famous wedding dress in history would make most a household name and a celebrated public figure. Not Ann Lowe (1898 - 1981). According to The Washington Post, when asked who made her bridal gown, Jackie Kenny told reporters, ‘a coloured dressmaker’. In fact, the only writer to correctly credit the designer’s work - a painstaking affair after a burst pipe meant she had to remake 10 of the 15 bridal party dresses at a personal loss - was The Post’s Nina Hyde. Unfortunately for Lowe, who since told interviewers that the first lady was very ‘sweet’, this was not the first time or the last that she would be overlooked and undervalued because of her race. She enrolled at fashion school in New York, only to be segregated from her classmates when her instructors realised that she was Black. In 1968, however, she opened her store, Ann Lowe Originals, on Madison Avenue and, today, her work is exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

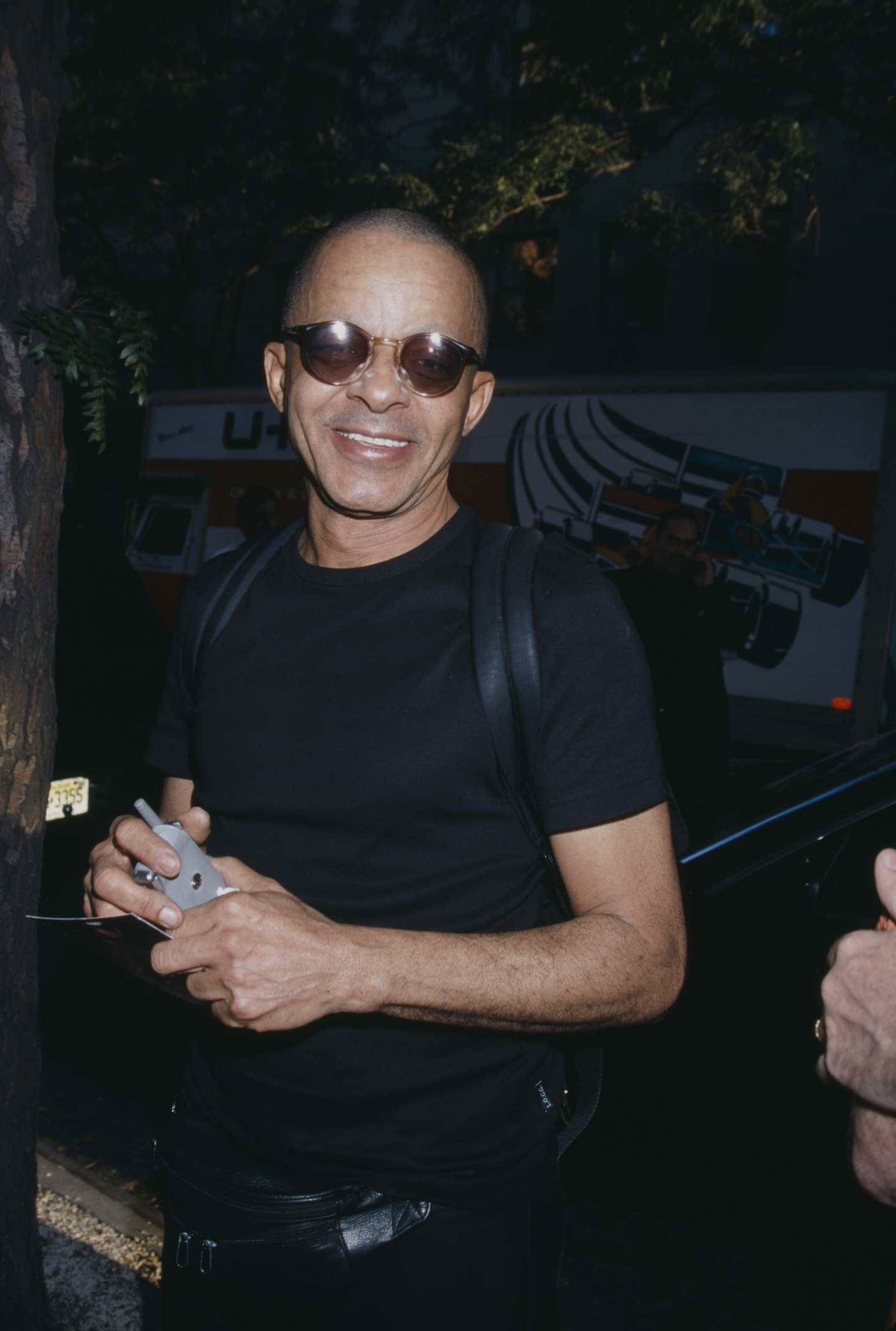

Patrick Kelly

In 2020, during the protests for Black Lives Matter, Patrick Kelly’s name started appearing in the news cycle under a new guise, The Kelly Initiative. This coalition of black professionals - founded by Kibwe Chase-Marshall, Jason Campbell and Henrietta Gallina - advocates for equal employment opportunities within the fashion industry for Black talent, and was named to honour the late designer. Kelly died from complications due to AIDS, at the incredibly young age of just 35, in 1990, but, as the initiative’s name clearly demonstrates, his legacy still has impact. Born in Mississippi, Kelly was the first American designer to be admitted into the prestigious Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter, the French fashion industry’s equivalent of the CFDA, and never shied away from bringing conversations about race into his work. (In 1985, five years after arriving in Paris, his collection featured a print showing a black face with red lips and white teeth in reference to the golliwog, a character in a children’s book that is now identified as a historically racist symbol.)

Willi Smith

Streetwear is a nebulous fashion term now used to describe anything from trainers to sweatpants to hoodies but to its inventor, Willi Smith (1948 - 1987) the genre couldn’t be reduced to mere garments. It was about real people, wearing real clothes. ‘I don’t design clothes for the queen, but the people who wave at her as she goes by,’ is one of his most famous sayings. His label, Williwear, was an immense success financially, making gross sales of $25 million a year by 1986, according to The Guardian. For Smith, his race had everything to do with it. ‘Being black has a lot to do with my being a good designer. Most of these designers who have to run to Paris for colour and fabric combinations should go to church on Sunday in Harlem. It’s all right there.’

Stephen Burrows

When Stephen Burrows (born 1943) participated in 1973’s ‘Battle of Versailles’ - not an epic period drama but a kind of international showdown between five design houses from France, and five from America - he won the appropriation of an industry legend. According to The New York Times, Burrows remembered of the event: ‘Saint Laurent came up to me and told me how much he loved my clothes. 'Your clothes are beautiful,' he said, and I just freaked out.’’ Although Burrows didn’t experience the commercial success of Willi Smith, for example, his knitwear designs were infused with the spirit of the era, and he was at the cultural epicentre of everything New York. As Pat Cleveland told The Times, ‘He was the center of the universe’.

Stella Jean

Italy’s fashion landscape would almost be entirely homogeneous were it not for Stella Jean, the designer whose father is Italian, and her mother Haitian. She received an early endorsement from Giorgio Armani, who famously shared his show space and communications team with the young designer in September 2013, having won Vogue Italia’s talent contest, Who Is On Next, two years earlier in 2011. Despite these outward successes, Jean has still struggled to make her voice heard when it comes to talking about inclusion. Speaking to British Vogue, the designer described what happened when she approached big media outlets about a social awareness project she launched in 2020 in lieu of a traditional catwalk show. 'Believe me, I knocked on every door. I [personally] wrote emails and letters to all the important Italian media and people who could help. And the sad thing is, only three people answered me,’ she said. She still, however, remained hopeful about how things might change - ‘But I’m optimistic – I don’t want to think it’s hypocrisy. I hope from now on they will be supportive’ - and will undoubtedly be a guiding force to make sure the opportunity isn’t squandered.

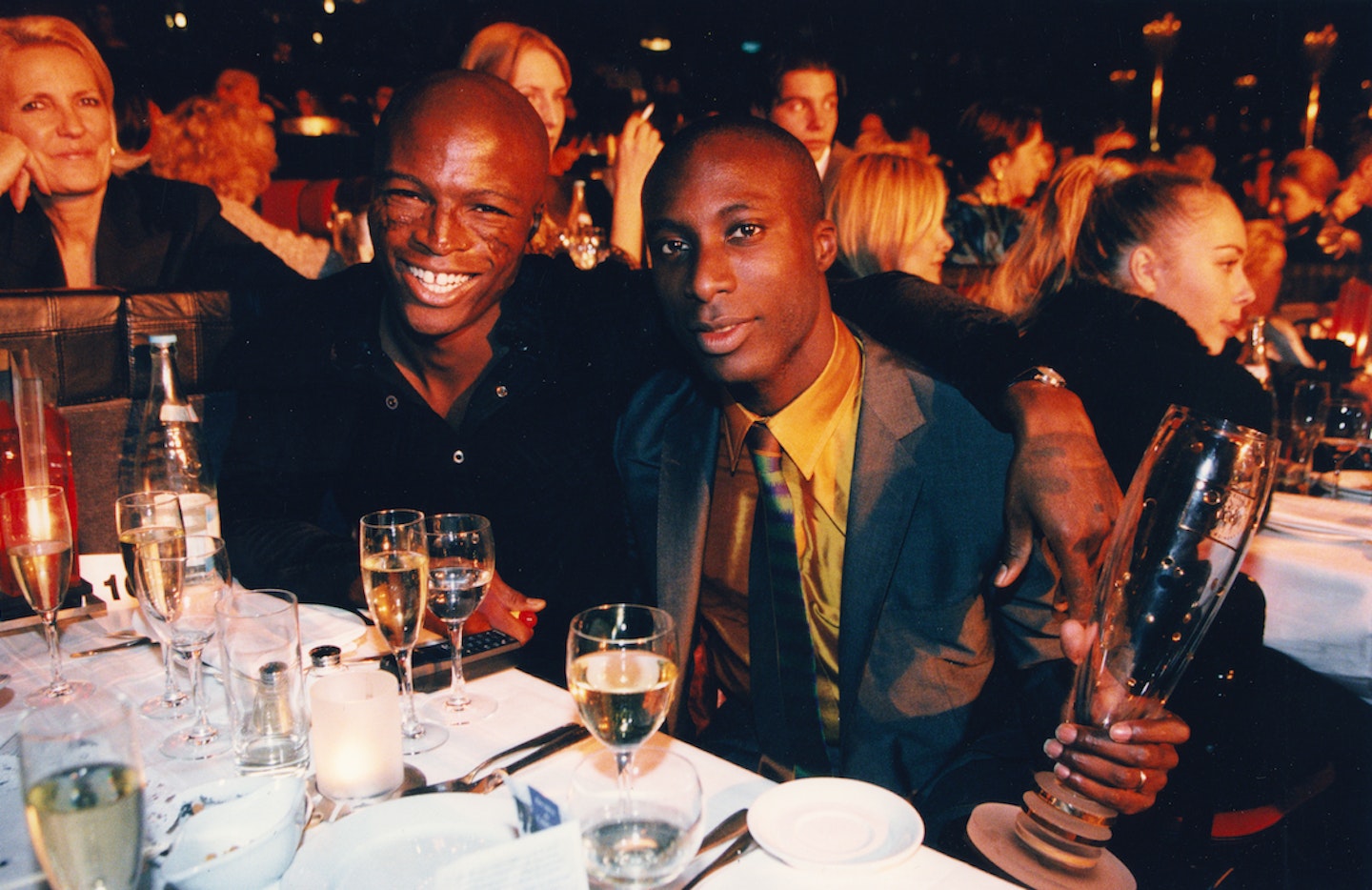

Ozwald Boateng

Ozwald Boateng’s suiting has appeared on every well-heeled man you can think of - Will Smith, Jason Statham (in Lock, Stock & Two Smoking Barrels), Paul Bettany (in Gangster No 1), Keanu Reeves, Daniel Day Lewis, Jamie Foxx and SATC’s Stanford Blatch - a fact that is entirely unsurprising when you realise that the tailor was the youngest to ever open a store on Savile Row (1995), and the very first to show his collection at Paris Fashion Week (1994). His Ghanian heritage is writ large in his creative imagination, inspiring his effervescent colour palette, and, married with the traditions of Savile Row, meant his tailoring appealed to a younger customer than the kind you would usually have found walking those streets in the ‘90s. In 2006, he was honoured with an OBE, and in 2018, contributed his dazzlingly bright suiting to Marvel’s Black Panther. At February's London Fashion Week, he returned to the schedule after a 12-year break with an extraordinary show at the Savoy Theatre, although 'show' doesn't quite do justice to the musical performances, spoken word recitals and the model line-up, which included the likes of Idris Elba, Dizzee Racal and Pa Salieu.

Patrick Robinson

Patrick Robinson has contributed to some of the most established and influential fashion brands of all time - Giorgio Armani, Paco Rabanne and Perry Ellis - but his career still seems to be defined by an ill-fated four-year stint at Gap. After parting ways with the company in 2011, Robinson recalibrated, launching his own e-commerce lifestyle brand Paskho, which sells eco-friendly travel apparel. The brand has always been closely aligned with sustainability, but the pandemic made it a core value, along with a responsibility to its community of workers. The Zen-Like Comfort Pants, made from a four-way stretch tech fabric, are the only way to travel.

Virgil Abloh

When Virgil Abloh passed away last year in November, his life (and game-changing contribution to the creative world) was mourned far and wide. Kai Isaiah Jamal, the poet and spoken word artist who collaborated with the designer at Louis Vuitton, said, 'I don't think he'll be remembered as anything but an icon. I don't think there's a pedestal high enough.' He was an industrious talent - holding two hugely influential roles (founder of Off-White; artistic director of menswear at Louis Vuitton) - who weaved the stories and memories of his Ghanaian heritage into his designs. As the tribute posted on his own profile recollected, 'He often said: 'Everything I do is for the 17-year-old version of myself'.'