‘Women are afraid,’ Orlagh explains in hushed tones. She’s angry. When we speak over the phone we take breaks - five minutes, 20 minutes; enough time for her to get to the safety of her car. It’s not because she’s upset - although it’s clear at times that she is - but because she’s afraid of being overheard. She’s scared someone might find out that she had an abortion.

It’s easy to assume that female oppression exists only in countries far away from the UK. Yet, Orlagh is living just 50 miles over the water from England in the Republic of Ireland. Last month’s referendum which approved gay marriage in Ireland was a source of hope for thousands all over the country that a move towards a more liberal future might be in sight - but for women like Orlagh, silenced and shamed by one of the most restrictive abortion laws in the world, there’s still a long road ahead.

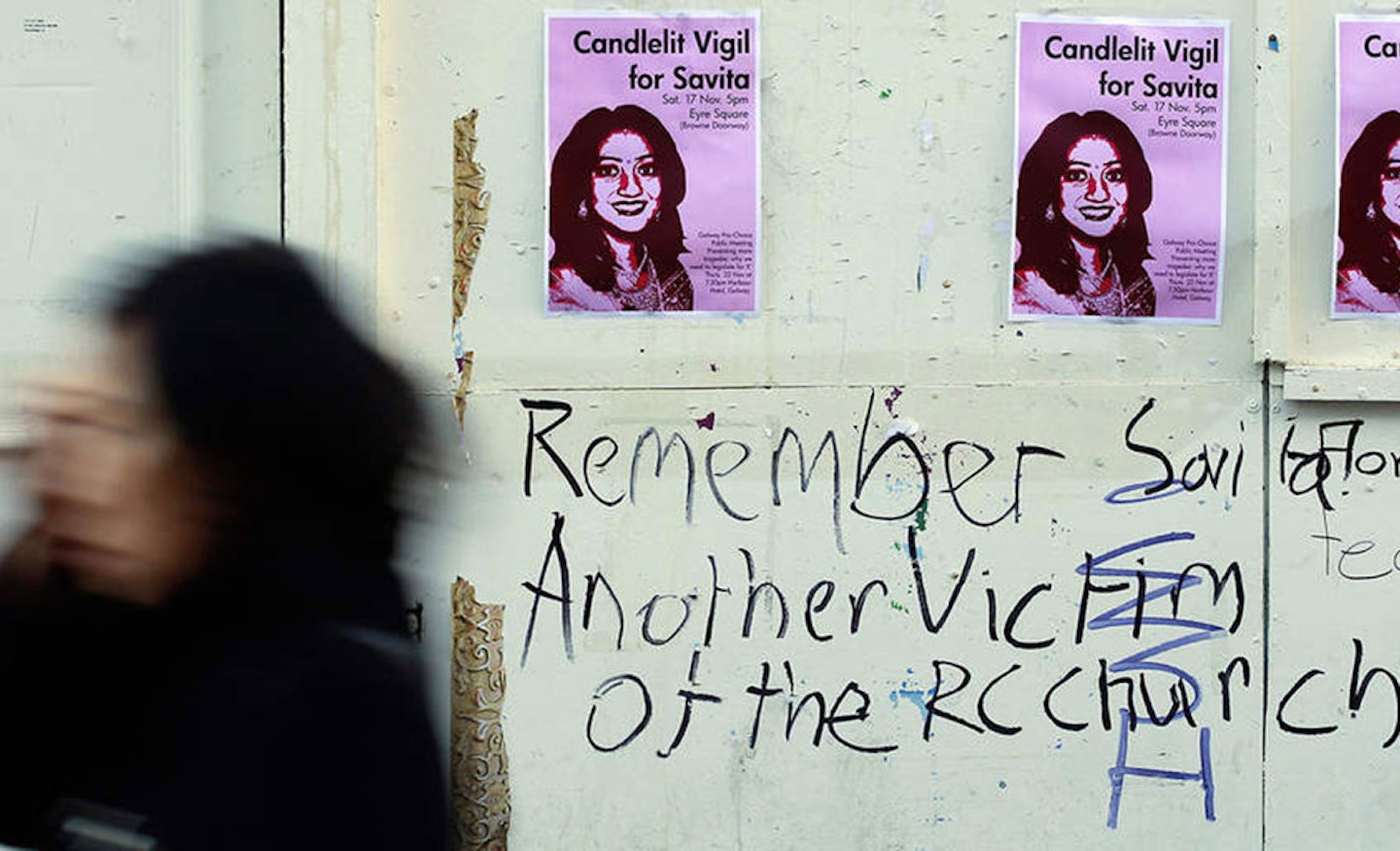

Last week, Amnesty International launched #SheIsNotACriminal as part of their My Body My Rights campaign. Their aim is to repeal the 8th Amendment of the Irish constitution, which equates the rights of a woman to that of an unborn foetus and to decriminalise abortion. Three years after the avoidable death of Savita Halappanavar, 31, who died after developing septicaemia following a miscarriage. Despite her pleas for an emergency termination, doctors in Galway refused on the grounds that Ireland is a 'Catholic country' and there was still a foetal heartbeat. Savita's death prompted global outrage and prompted Ireland to pass the Protection of Life Bill 2013 which allows women to undergo abortions if their lives are at risk (including suicide). However, in all other the law still criminalises abortion in favour of pro-life activists and puts women’s health in grave risk.

Still today, in 2015, if Irish women seek abortions with no direct threat to their lives, both the woman and the abortion provider risk being imprisoned for up to 14 years.

This means that currently, 10 to 12 women journey to England every single day for private terminations. That's more than 4,000 per year. The cost of having a termination abroad - often in excess of £2000 - means that some women, including rape or incest survivors, women whose pregnancies won't survive or have severe foetal impairment, are forced to go to term, sometimes carrying dead foetus’ in their wombs for months in case there is any life left, since inducing a foetus is illegal.

As a result, many resort to desperate and dangerous means of terminating their pregnancy, by ordering pills online to induce ‘DIY’ abortions. Yet the divisive nature of the subject in a pervasively Catholic country means reforms to protect these women are not currently being undertaken.

Orlagh, 38, an artist, was 35 when she found out she was pregnant after a one-night-stand with her childhood sweetheart. ‘I was broke, and we weren’t in a relationship,’ she explained from her home in West Ireland. ‘Instinctively I wanted to keep the baby but, as much as I tried to figure out how I could, my circumstances simply wouldn’t allow it.

‘It wasn’t easy. It needs to be said over and over that it is never easy no matter what circumstances. It was the saddest thing I’ve ever been through.’

Orlagh was forced to borrow money from her sister to book flights to Manchester to go through with the termination. ‘They recommend you bring someone with you, but I couldn’t afford that,’ she said. ‘They recommend that you stay overnight, but I couldn’t afford that either.'

On arriving, Orlagh was told that the price for the procedure had increased, bringing the total amount she had to borrow to more than £1000. Emotionally overwhelmed and unsupported she paid and then made her way to her flight home, alone. ‘At the airport I couldn’t actually stand up,’ she explained. ‘I wasn’t prepared for emotions I felt, the raw grief. It was like being in a graveyard on your own, burying a coffin. I didn’t go out for six months afterwards. Three years on, I can’t have sex. I’m petrified of getting pregnant.’

In neighbouring Northern Ireland (NI) the situation is equally conflict-ridden. Laws there dictate that abortion is only legal when there’s a risk of real or serious long-term damage to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman. Last week, Sarah Ewart, backed by the Human Rights Commission (NIHRC) sought to legalise abortion in the cases of rape, incest or ‘serious malformation’ of a foetus by challenging the High Court in Belfast. If it’s successful, it could be the first crucial step in setting a precedent for change and affording women the very basic right of having autonomy over their own bodies.

Nicola, 36, from Ulster, was 19 weeks pregnant when she was told her baby had fatal foetal abnormalities and wouldn’t survive. Immediately she asked when she would be induced to end the pregnancy, only to be told that it would be illegal under Irish law to do so. Unable to afford to travel to England, she was forced to carry around her baby, who she named Sam, for five weeks until he died - at the risk of her own health, physically and mentally.

‘When everyone else was going for scans to see how well their baby was doing, I was going to see if mine had died yet,’ Nicola, from Ulster, said. ‘In the third week the nurse told me that it was difficult to see Sam - he was ill and curled up in my tummy. I had to walk around for the rest of the day, feeling him kicking, knowing he was hurting, and dying, without being able to hold him.

‘I’m at peace with losing my baby now, five years on. But I’m not at peace with the fact that, even now as I speak, there are women out there going through the very same thing. Even if they are financially and physically able to travel, there’s the disgraceful fact that many babies’ remains are sent home to Ireland by courier. How can women grieve like that?’

For women like Nicola and Orlagh, the laws in Ireland and Northern Ireland not only fail to reflect the society they want to be a part of and put their physical and emotional wellbeing in jeopardy, but also perpetuate shame and stigma which silences women’s voices.

‘I don’t understand how we’re not talking about what this law is doing to women,’ says Orlagh who, like Nicola chose not to use her surname for this article to protect her anonymity. ‘It’s real. But we’re pretending it doesn’t happen. These are real stories of real women who are going through unnecessary and violent trauma. Why?

‘I’m angry that I had to go through all of that, but I’m twice as angry as I can’t even talk openly about it. I can’t have an open conversation about an experience that has changed me, even that conversation might help the situation or other girls.’

According to Orlagh, in many parts of Ireland the subject of abortion so taboo that it’s essentially erased from communities, the conversation impeded by historical religious beliefs and social shame. She hasn’t told even her own parents to protect them, and confided in a few trusted friends and her sister. But she believes by raising the voices of those women oppressed by the law, change could happen.

‘That shame is still here so strong in this country that women like me are afraid to talk about it. We need a referendum on abortion; we need reform,’ she says. ‘Women should have, at the very least, rights to decide what happens to their own bodies. And women’s voices - us, the women suffering - have to be heard. We will be heard.'

Help Amnesty International decriminalise abortion in Ireland by signing their petition here and tweeting using #SheIsNotACriminal