Terri White, editor-in-chief of Pilot TV, says the rise of ‘poverty porn’ exposes a bigger problem in society in general.

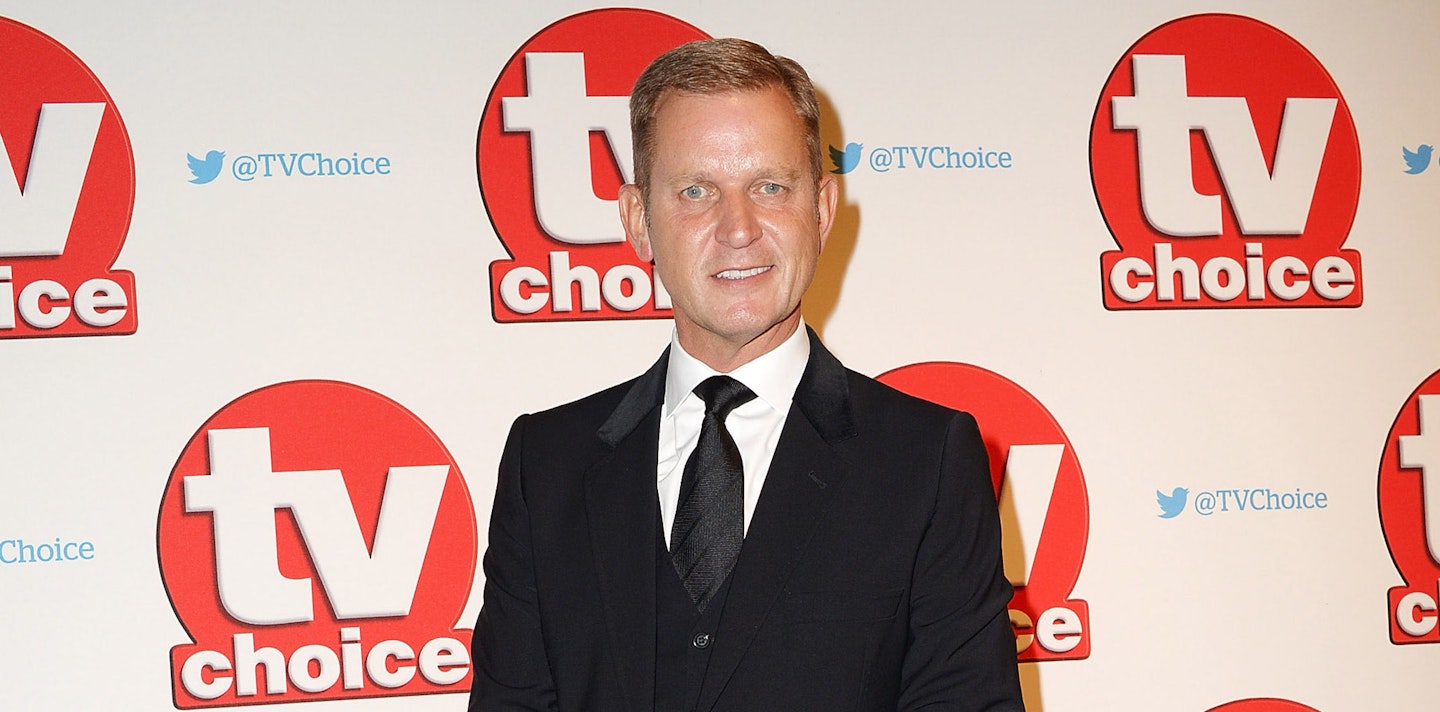

When the decision came, it didn’t surprise anyone: ITV’s The Jeremy Kyle Show was to be permanently cancelled. It came just days after Steve Dymond, who’d been filmed for a show, had reportedly taken his own life.

It’s important to say that we can’t possibly know the circumstances behind Steve’s death (and suicide is rarely, if ever, the consequence of one event), but it has forced questions to be asked about what he’d endured, just a week before his death, during the recording of the show. A programme that still, after 14 years, boasted a massive 22% audience share.

Take a look at the timeline of events that led to The Jeremy Kyle Show's cancellation:

The Jeremy Kyle Show cancellation timeline slider

1 of 4

1 of 4ITV confirms the episode featuring Steve Dymond will not be aired

After Steve Dymond died shortly after filming, an ITV spokesperson issued a statement saying: "Everyone at ITV and The Jeremy Kyle Show is shocked and saddened at the news of the death of a participant in the show a week after the recording of the episode they featured in and our thoughts are with their family and friends."

2 of 4

2 of 4The Jeremy Kyle Show is suspended with immediate effect

Bosses at ITV confirmed that filming and broadcasting were suspended "with immediate effect" as that day's edition of the show was replaced at short notice with a repeat episode of Dickinson's Real Deal.

3 of 4

3 of 4The Jeremy Kyle Show is permanently axed

ITV CEO Carolyn McCall issues a statement reading: "Given the gravity of recent events we have decided to end production of The Jeremy Kyle Show. The Jeremy Kyle Show has had a loyal audience and has been made by a dedicated production team for 14 years, but now is the right time for the show to end. Everyone at ITV's thoughts and sympathies are with the family and friends of Steve Dymond."

4 of 4

4 of 4Jeremy Kyle breaks his silence

"Myself and the production team I have worked with for the last 14 years are all utterly devastated by the recent events," the 53 year old presenter said in a statement, breaking his silence on the show's cancellation. "Our thoughts and sympathies are with Steve's family and friends at this incredibly sad time."

I’d once been a viewer. It was something I only ever did by myself, after dark. I’d close the curtains, turn off the lights, pull the covers over my head and press play. The episodes were titled from the tame (‘I’ll prove you’re the dad’) to the salacious (‘Have I been having sex with my brother?’) to the ridiculous (‘My boyfriend thinks I cheated with another man through a letterbox’). My viewing peaked when I lived in New York: it didn’t just quench my thirst for home, but for where I was from.

As a working-class woman, I recognised the people – mainly white and poor – who shared their stories, who we may have thought were talking about a fumble in a car park or a fight over an ex in a burger shop. But, if you listened, really listened, their stories were ones of pain and struggle, often the grinding misery of living in poverty.

Stories and nuance were drowned out by Jeremy shouting at guests to ‘put something on the end of it’ and ‘get a job’ while they sat hunched and broken, trying to keep their indignities and worst moments of shame covered while Jezza tugged at the scab.

I stopped watching, knowing the narrative word for word, feeling its stain. A narrative that, according to both those who have worked and appeared on the show, was created with significant effort and deliberate emphasis. Their accounts all circle the same themes: manipulation, neglect, irresponsibility. Producers whispering in their ear about their ex-partner – once lover, now sworn enemy – moments before they’re pushed out on stage, weaving from fury. Mental-health issues ignored. Guests being given access to plenty of free booze the night before. The morning after, often hungover, told to wear tracksuits, clothing deemed more ‘appropriate’. Questionable after-care.

But let’s be clear: the show only works, is only remotely acceptable, if those who appear on it are not ‘us’. Are ‘other’, are archetypes of the feckless, lazy, benefits- swindling outsiders that we’ve been told deserve not just our scorn, but the absence of the respect you’d afford another human being. If we believed they were just like us, then Christ: how barbaric. And who wants to watch that? Not a million people. That would make them all monsters. And an average of a million people an episode did watch. Over 3,320 shows.

It’s true that we exist in something of a binary TV landscape – the rise of cinematic TV (quality channels like HBO and content platforms like Netflix) has meant we now see the very best of TV on our screens. But at the other end of the scale, we have Can’t Pay? We’ll Take It Away! (not my exclamation mark); On Benefits And Proud (plus the spin-off, Gypsies On Benefits And Proud); as well as Benefits: Too Fat To Work.

This poverty porn television has become an odd outlier in societal discourse. On one hand, Twitter rages (often rightly) at offensive language, classist attitudes, the casual demonisation of those who are poor. Then you turn on the telly and see those who are jobless/overweight/mentally ill/ on the breadline strung up, bellies-out, for our entertainment.

This isn’t – as some commentators have claimed – about patronising the working class, taking away their informed choice. It’s about having a duty of care to people, whether they choose to put themselves on TV or not. And it’s this duty of care that must be at the heart of however we move forward.

The Commons Media Select Committee is to investigate whether TV companies give guests enough support, but it’s clear that current self- regulation isn’t enough. (ITV is investigating the circumstances around Steve Dymond’s appearance but maintains the show had a ‘significant and detailed’ duty of care process. Steve’s fiancée also praised the show’s after- care, while Jeremy Kyle said he is ‘devastated’ by the death of a guest and cancellation of his show.) And the TV regulator Ofcom, if it’s going to bare its teeth, needs to update its code of conduct, which currently only has a duty of care to under-18s.

This, though, the finger-pointing at the show, production company, network, doesn’t absolve us: the great British viewing public. We should vote with our remotes. Say no to poverty porn – a particularly perverse pursuit in a time of crippling austerity, when new stats have shown that half a million more kids are living in poverty than in 2010; prove that we’re better than this, we have more humanity. That these shows aren’t OK; in the light or the dark