Gruelling schedules, obsessive fans, and a merciless tabloid press: boyband fame is sold as a dream to young stars, but the reality is far from the fantasy. ‘No one goes through that level of fame and comes out the other side completely sane or not mentally affected by it,’ notes Robbie Williams in a must-see, three-part BBC documentary.

Boybands Forever examines the golden age of ’90s and noughties pop groups, hearing from members of Westlife, Five, East 17, 911, Blue and Take That. The ‘Geppetto’ of boy bands, Simon Cowell, provides a running commentary – nodding to the life promised to young stars versus what the truth entails, he quips, ‘If you don’t want that, then be an accountant.’

After the documentary aired on BBC2, Williams, for his part, penned an open letter to Take That's former manager, Nigel Martin Smith, and shared it on Instagram. He expressed his disappointment at Martin Smith's lack of self-reflection in the 20 years since they last spoke. The 'Angels' singer also detailed the undeniable and damaging effects being in Take That had on all five members writing: 'Howard – contemplated suicide when the band ended, Mark – addiction, alcoholism, rehab, Gaz – bulimia, Me – I think that one is well-documented, Jason – whatever effect Take That had on him is so painful he can't even be part of it' – all of which is on the record.

If not already illustrated by Williams' public response, the documentary uncovers troubling details about the era, for which a collective period of reckoning is long overdue. It is particularly poignant following the tragic death of One Direction’s Liam Payne last month. More than 130,000 people have already signed a petition for ‘Liam’s Law’, which would necessitate regular mental health check-ups, adequate rest periods and the presence of mental health professionals on set during young artists’ careers.

‘The Liam Payne story hit me hard to be honest with you,’ Terry Coldwell from East 17 tells us. ‘You can have all the fame in the world, all the money in the world, but it can't help your problems. There should be some sort of aftercare put in place for people struggling.’

‘This should have happened years ago,’ echoes Lee Brennan from 911, who also appears in the documentary. ‘When things start to take off, you’re learning on the job. I found things were building up slowly, and it got more difficult towards the end.’ 911 split up in 2000 after five years together, but Brennan says he lost the next 10 years of his life trying to come to terms with the experience. ‘I didn’t know what to do with myself,’ he admits.

It’s a kind of fame, by all accounts, that made healthy, private relationships near impossible to maintain – in fact, they were often discouraged. In the documentary, former tabloid journalist Paul McMullan recalls that hiring women to seduce boyband stars who were already in relationships was standard practice, which is exactly what happened to Five star Richie Neville while he was dating Billie Piper.

We also learn, in hindsight, that Brian Harvey of East 17 was scapegoated and encouraged to talk about his drug habit during an interview in 1997 that ultimately cost him his place in the band. ‘I think we were exploited,’ says his bandmate Coldwell. ‘I think every band is exploited, especially if you’re getting into the music industry at a young age. I was 16 when I joined the band and 17 when we got a record deal.’

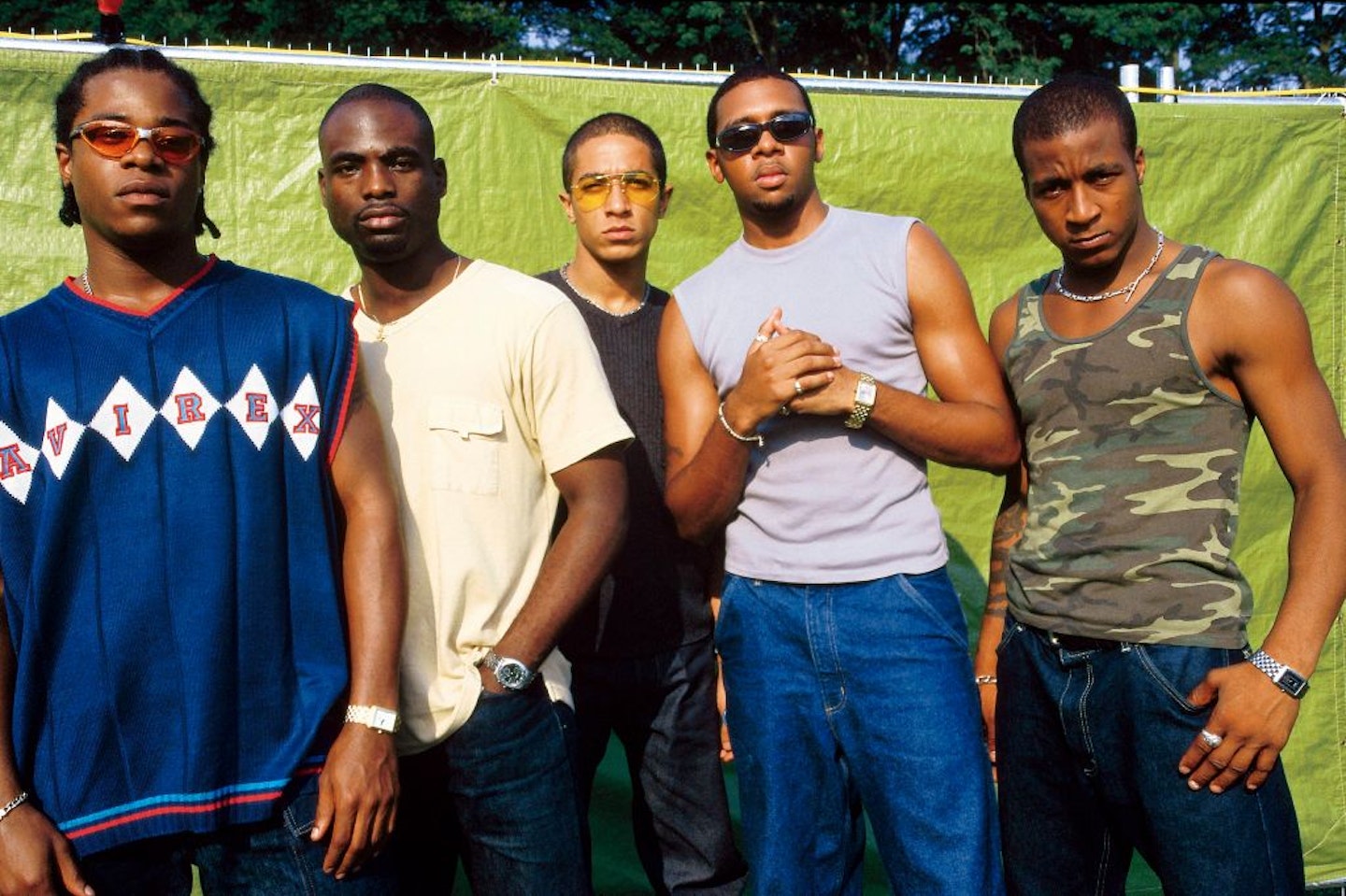

It's unsurprising that few were able to navigate this era unscathed – especially those who faced further intersectional challenges. Andrez Harriott from Damage, for example, details his experience of being in one of the only black bands on the UK scene at the time. ‘We were acutely aware that we were working extremely hard and not getting the traction that some of the other artists were getting. We were the only black male band on most of the billings and we had an R&B sound. That wasn’t what radio wanted to hear.’

Unlike their contemporaries, Damage was denied primetime slots on radio and TV, seldom invited to be on the front cover of magazines and was given a significantly smaller marketing budget than the other bands on their label. Harriott remembers being encouraged to make their image and sound ‘more malleable to the British audience’ and they faced an ongoing struggle between credibility and commercial success.

’30 years in and we have a band that is still together, albeit four of us out of the five, and we have a legacy in British music which is quite incredible,’ he hastens to add. ‘I wouldn’t trade that.’

Boybands Forever goes a long way in highlighting how complex this kind of legacy can be. For many, the lives and careers they have gone on to have make the psychological toll a worthy trade off – but others are not so lucky.

‘Making sense of all those things we’d been through as a group took many years,’ adds Brennan – recalling how he’d often lock himself in his hotel room for respite during the peak of 911’s fame. Despite the band being formed more than a decade later, Payne previously shared in interviews that he and the other One Direction members were often confined to their hotel rooms for their own security while on tour as well. It's difficult to watch the series and view any of these experiences in isolation.

‘The tragedy of Liam will create positive change going forward,’ Brennan hopes, ‘even if it’s very late in the day.’ The revelations in Boybands Forever shine a light on an industry that, decades on, can still treat young stars like commodities – it’s time for that to change.

Watch ‘Boybands Forever’ on BBC Two and iPlayer from 16 November

Nikki Peach is a writer at Grazia UK, working across pop culture, TV and news. She has also written for the i, i-D and the New Statesman Media Group and covers all things TV for Grazia (treating high and lowbrow shows with equal respect).