Excitement and anticipation for Marvel’s Black Panther – which is finally out in February – has been at a fever pitch for months. The reaction to the snippets and trailers alone tell us the film is definitely going to be a Cinematic Event, for Marvel fans in general but especially to the worldwide black community.

When I saw the cast at the premiere in Los Angeles on Monday, in all their incredible outfits, just radiating black excellence from all over the black diaspora, I’ll admit I got a little bit sentimental. My cheeks almost ached from grinning but all the while, in the back of my head as I scrolled through those pictures, I was envisioning the impending diaspora wars that were sure to break out on Twitter, which has become the main battleground, and apparently, I wasn’t the only one.

Diaspora wars stress me out. It’s like looking at your parents arguing. It’s painful. They often consist of insults, "jokes" and pettiness that more often than not strays into harmful rhetoric that at its worst regurgitate internalized racism. That doesn’t mean we can’t have valid and legitimate discussions about cultural influence, cultural knowledge, blind spots, but when Twitter is the platform for these conversations, too often they descend into nothing more than insults. Social media has done something amazing: it’s allowed traditionally separate communities of the black diaspora to connect and learn from one another. A kind of cultural exchange. Black (African American) Twitter, Island Twitter, West African Twitter, East African Twitter, South African Twitter, Black British Twitter, Afro-European Twitter. We’ve seen all the ways that we’re different and all the ways that we are uncannily similar.

More than other Marvel comics – with the exception perhaps of X-Men – what makes Black Panther so interesting and so political is the negotiation between the reality and the writers’ world building. Marvel seems to have leaned into the cultural conversations that arise from this by releasing the film during Black History Month in America. It’s no secret that the film has huge cultural significance. In 17 Marvel movies, Black Panther will be the first to feature a non-white person as the titular and central character. There was no way Black Panther was going to escape politicized conversation, and the director Ryan Coogler acknowledged that.

Coogler told Rolling Stone ‘I think the question that I’m trying to ask and answer in Black Panther is, “What does it truly mean to be African?” The MCU [Marvel Comics Universe] has set itself in the real world as much as possible – so what does it mean for T’Challa to move around as this black man in a movie reality that tries to be a real world?’

Read More: Look at the stunning outfits at the 'royal attire' themed Black Panther premiere:

Debrief Black Panther Premiere Outfits

1 of 21

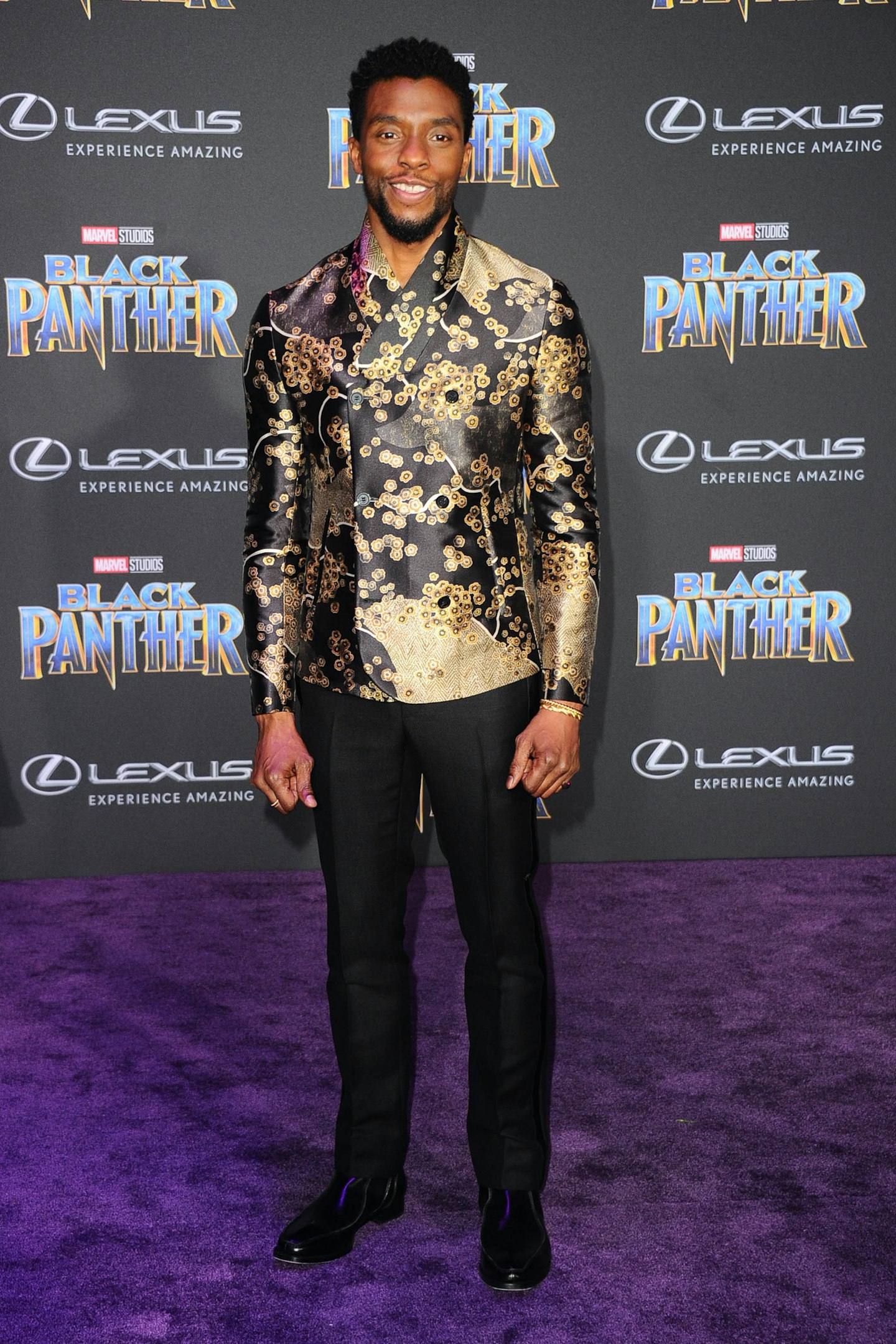

1 of 21Chadwick Boseman

2 of 21

2 of 21Lupita Nyong'o

3 of 21

3 of 21Michael B Jordan

4 of 21

4 of 21Danai Gurira

5 of 21

5 of 21Angela Bassett

6 of 21

6 of 21Daniel Kaluuya

7 of 21

7 of 21Zinzi Evans & Ryan Coogler

8 of 21

8 of 21Donald Glover

9 of 21

9 of 21Janelle Monae

10 of 21

10 of 21David Oyelowo

11 of 21

11 of 21Issa Rae

12 of 21

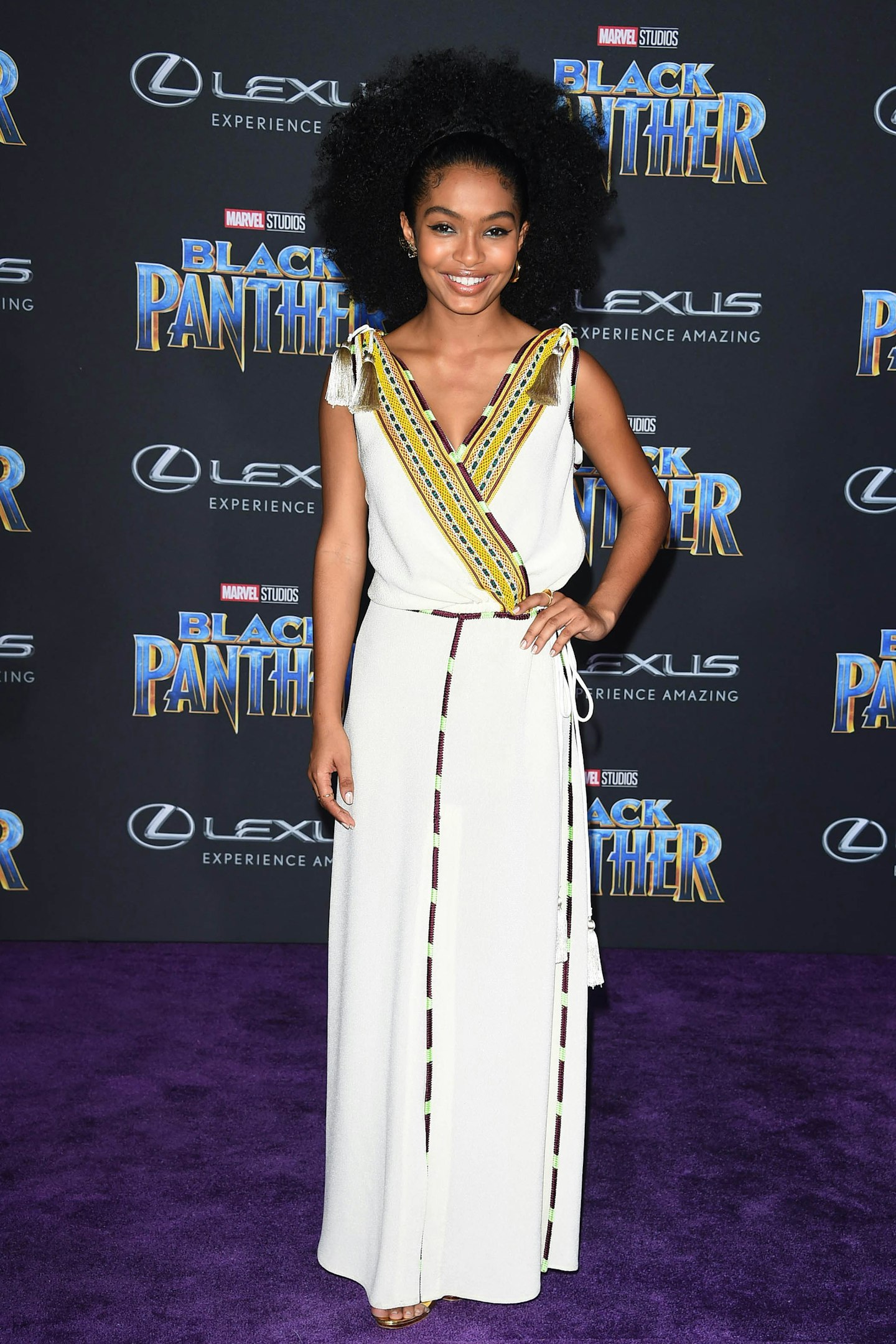

12 of 21Yara Shahidi

13 of 21

13 of 21Miles Brown

14 of 21

14 of 21Angel Parker

15 of 21

15 of 21Mike Colter

16 of 21

16 of 21Janeshia Adams Ginyard

17 of 21

17 of 21Marija Abney

18 of 21

18 of 21Tanika Ray

19 of 21

19 of 21Connie Chiume

20 of 21

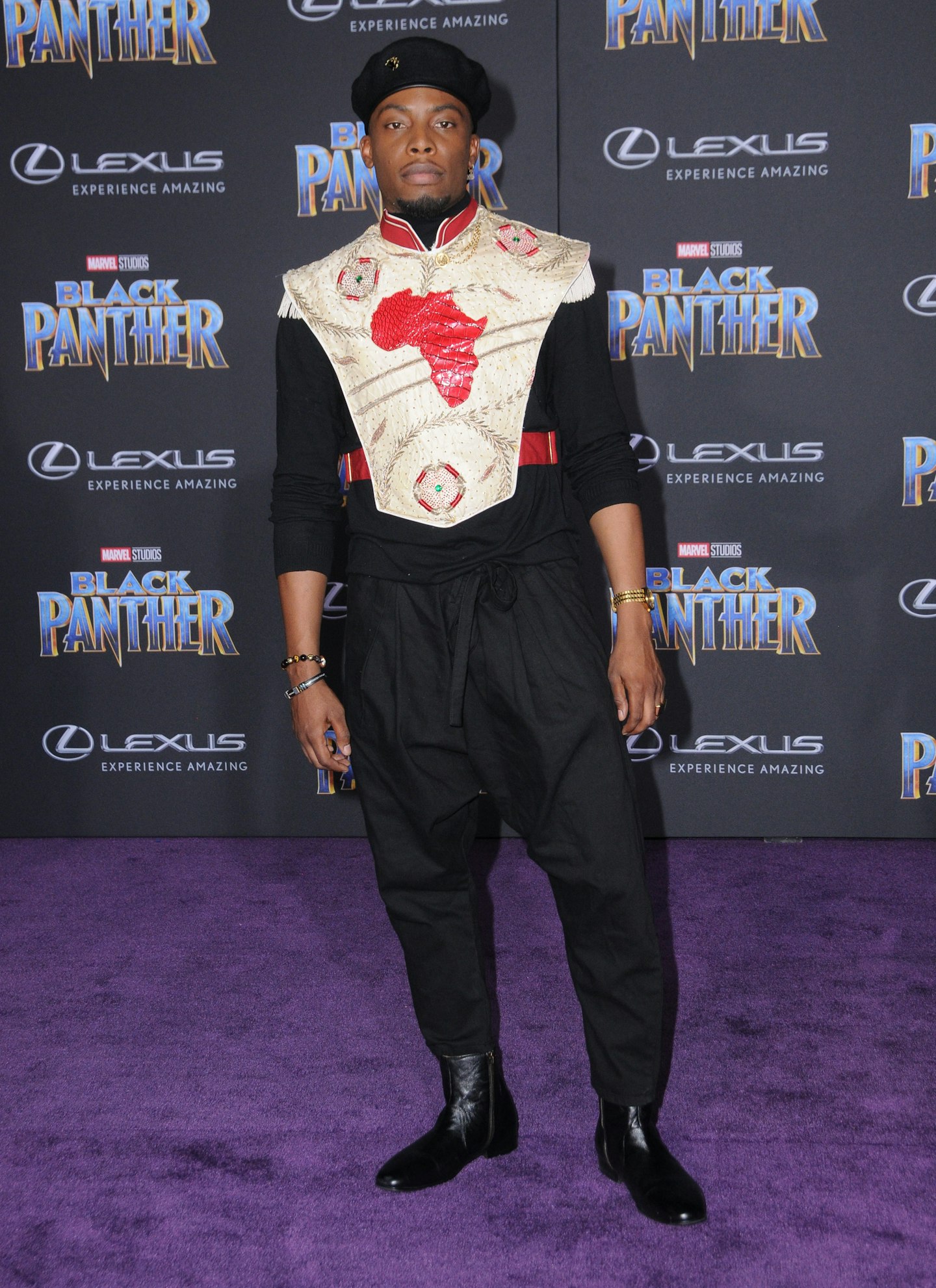

20 of 21Woody McClain

21 of 21

21 of 21DeWanda Wise & Alano Miller

Coogler’s question makes me think about what Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s intentions may have been when they first came up with T’Challa and Wakanda. Black Panther first appeared in Fantastic Four #52 in 1966, during the Civil Rights era. There’s no doubt Lee and Kirby saw the marches and the police brutality. In creating Black Panther, they created a man just as smart if not smarter than the long-established white superheroes, and just as powerful too, in an attempt to counter the single story that depicted black people in a derogatory light.

But what does it say that T’Challa is from a fictional African nation, and a king too, as opposed to an ordinary working African American man? Perhaps it was a way of tempering Black Panther’s radical nature like other changes later in the character’s story, most prominently the changing of his name from Black Panther to Black Leopard to sever any association with the antifascist group. Writing Black Panther as an African keeps him separate from the protests in the United States and a result the superhero and Wakanda, the most technologically advanced nation in the world, are a utopia out of reach.

Wakanda’s isolationism from the rest of the African continent and from the rest of the world sparked questions. How could the most advanced nation in Africa, indeed the world, not come to the aid of the countries around it?

But Marvel stories develop. The comics showed T’Challa trying to negotiate how he as the leader of a secret nation would interact with the wider world. He spends time with the people of America’s Black South, he fights against the injustices of a fictionalised apartheid South Africa, in one version he meets MLK and Malcolm X. The writers didn’t hesitate to show the ways an African king might find life in America a little alien, highlighting the differences as sources of curiosity as opposed to superiority or bitterness.

He’s an agent of cross-cultural discussion. Black Panther seems to demonstrate the diversity of the black diaspora and the clashes and embraces that happen within.

It’s obvious that I am an idealist. But I don’t think it’s possible to over-exaggerate the significance of a pop cultural phenomenon like this for the whole diaspora. The release of *Black Panther *should be a uniting moment. The only victor of diaspora wars is white supremacy, and white supremacy is global. Maybe it’s a lot to put on one film, but *Black Panther *could be the catalyst for healthier cooperation and discussion between black diaspora groups. I'm not the only who hopes so either.

**Follow Aida on Twitter @**kidisalrightkidisalright

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.