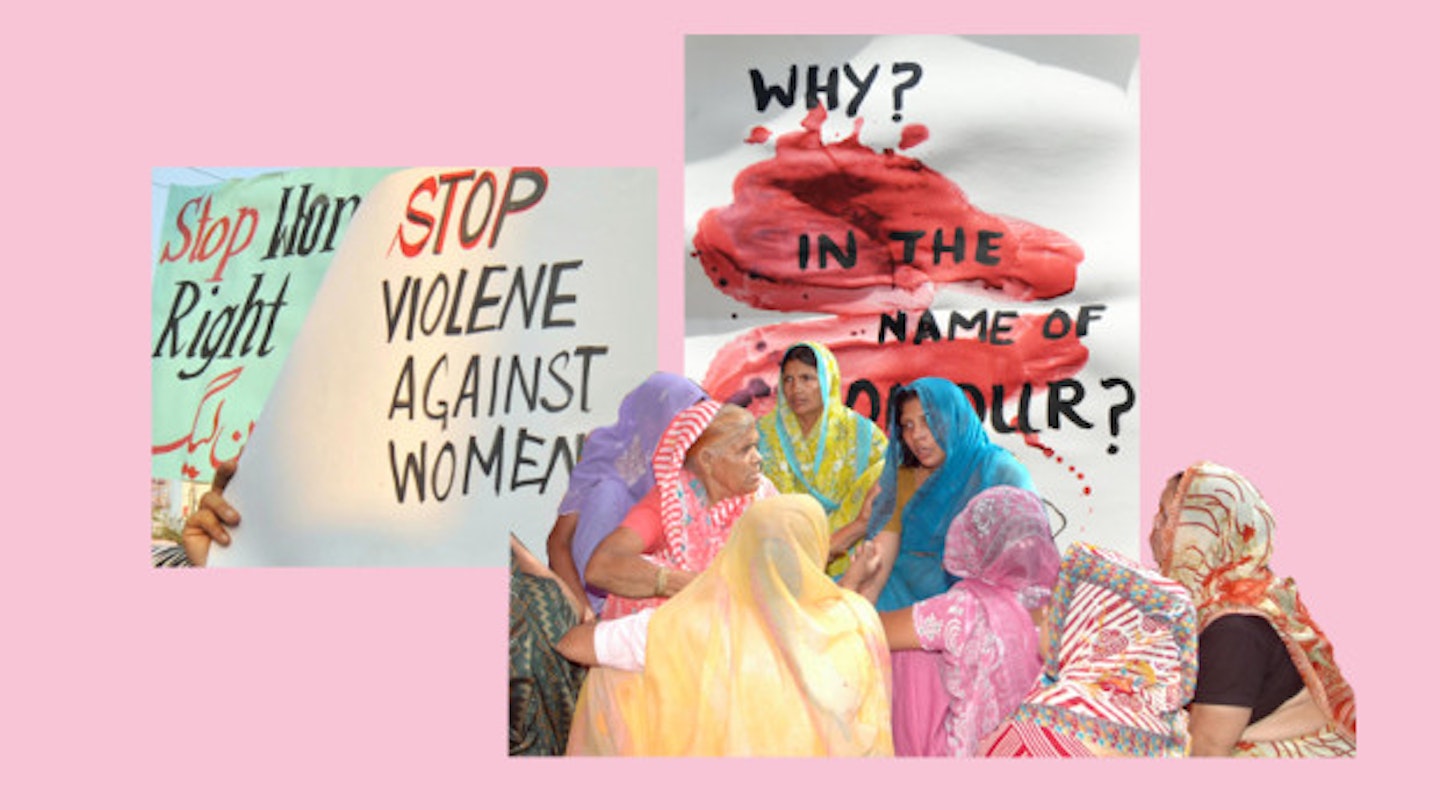

This summer, the international media shone a spotlight on Pakistan after a spate of so-called honour killings took place in the country. In July, Bradford-born Samia Shahid was strangled by her first husband after divorcing him. That same month, Pakistani model Qandeel Baloch hit headlines after she was murdered by her brother for her supposedly provocative selfies.

It’s not hard to see why the assumption still persists that honour-based violence - crimes committed to ‘protect’ the so-called honour of a family or community - only happen in the non-Western world. A problem for other people, elsewhere. A quick browse the Internet reveals that India has an estimated 1,000 honour killings every year while there have been 297 cases in Pakistan this year alone.

However, the sad reality is that honour-based violence has happened and continues to occur here in Britain. More than 11,000 incidences of honour crime were recorded by UK police forces during 2010-2014, ranging from forced marriage to female genital mutilationwhile there were 18 recorded cases of honour killings in the UK over the same period. Shafilea Ahmed, a 17-year old British Pakistani girl from Bradford is perhaps the most reported on example of an honour killing on British soil.

It’s easy and perhaps even tempting to think of these as extreme one-off cases, but the reality is that many British women privately contend with honour-based abuse in their daily lives– it could be happening next door to you and you wouldn’t necessarily know. There’s an estimated 12-15 honour killings every year in the UK, according to the Halo Project - but the figure could still be much higher as so many go unreported as victims might fear implicating their family or those in their community.

The stats don’t take into account the number of schoolchildren who are taken abroad during summer and don’t return, for one. Back in 2006, 250 girls aged 13-16 were taken off the school register for that same reason.

While tabloids would have you believe that honour killings have long been associated with Islam, the practice has also occurred in Sikh, Hindu and Christian communities as well. That’s not to say mainstream religions justify honour killings though. Despite the fact that this is ultimately a cultural as opposed to a religious issue religion has become synonymous with honour killings: the supposed shame which causes an act of violence to be carried out in the name of a long-held notion of ‘honour’ is seen to come about when traditional cultural beliefs are not conformed to, wearing ‘western clothes’ or dating someone from a different culture can increase a woman’s risk of honour-based violence.

Unsurprisingly, getting survivors of honour-based violence to talk to me was tough, even anonymously. But for the women I did speak to, one clear pattern emerged: these crimes were driven by control, to the extent that these women had any autonomy in their own lives.

One young woman spoke to me about how, in her family notions of their collective honour were projected onto her virginity, or lackthereof. 'It was like I was a walking hymen. Every day of my life was lived to preserve my stainless, unblemished virginity,' Serena*, 17, a student of Pakistani heritage, tells me. 'I grew to believe my virginity was a source of superiority and good virtue on which I could stand upon, in comparison to other women who had ‘gone astray' and given into their desires like beasts, obeying animal urges. I didn't pride myself on my intelligence or personality. It was solely pride in the fact I was a chaste woman, a godly woman.'

Any threat to or compromise of her virginity triggered the implicit threat of violence. 'I was bound to obedience like there was a rope around my neck,' Serena agrees. 'My father frequently asked if I ever had a boyfriend. He was suspicious and used to check my phone most days for any male-related contact.'

In some cases, the hijab is even used as a tool to enforce women’s ‘modesty’. While wearing one is a deeply personal choice for many Muslim women the world over – and one that many take pride in making – this isn’t the case for everyone. Serena was forced to wear it: “I wondered time and time again what it’d be like to live like everyone else, to feel the rain and wind on my hair and face, not choking in a black shroud. Unveiling would have stripped me of my ‘honour’.”

For the other young women I spoke to it was their sex lives which became the property of other members of their family. They spoke of being crippled by the fear of dishonouring their families if their secret boyfriends were ever discovered, everything had to be clandestine. 'I used to get a beating over taking selfies on my phone or waving to a friend that was a boy when I was 10 and they [were minor incidents],' Halima agrees. 'I knew that if my parents found out [about my boyfriend of four years], my life would go down the drain.' She even took extreme measures like hiding her phone in her bra to conceal evidence of her ‘double life’. 'I would say I needed to stay late after school and then we’d go and spend time together where I knew I wouldn’t be seen not just by my family but also a lot of the community since my dad is well-known. I constantly had to watch my back.'

For most, if not all, of the women I spoke with, it was evident that shame and guilt were an invisible backdrop for their young adult lives. They lived under the pressure of upholding not only their own ‘honour’, but the ‘honour’ of their families as it was impressed upon them. Shame was most powerfully present in their relationship with their own bodies. 'When you cover [your body] for ‘honour’ you, by necessity have to see these parts as forbidden and a source of great shame if they’re exposed,' Serena says. 'My family taught me via their abusive indoctrination that I was like a piece of meat, unless I hid it all. I was made to feel that my body was repulsive, sunk in deep.'

'I loathed anything and everything feminine about myself, my breasts and my thighs,' she adds.

Honour killings don’t just affect those who have their lives taken from them; it can affect everyone involved, from those ‘left behind’ like the boyfriend of honour killing victim Banaz Mahmood who committed suicide this year, a decade after her murder, to those at risk to who feel that there’s no opportunities to seek help or escape.That’s not to say that help isn’t available: Karma Nirvana,the UK’s only forced marriage and honour violence helpline, answers more than 750 calls on average every month – and the number is increasing.

The experience for young LGBT women I spoke with was equally fraught. Serena, who’s bisexual, explained that it added to her burden, “to admit that I looked dreamily at and longed after girls, would have robbed me of my honour indefinitely,”

For Alya*, 25, a queer, sex-positive ex-Muslim, being constantly conditioned to feel shame has impacted her chances of forging relationships with women: '[it] influences everything I do. That process of 'what will so and so think' or 'what if it gets back to family' echoes in my head. I feel the damage is done as [it] permeates into my most intimate relationships.'

Leaving their religion is equally comes fraught with risks and by no means an easy decision to make. While Alya ‘came out’ to her family, she no longer feels safe in her predominantly Asian, Muslim area: “I have been told (by ex-friends and acquaintances) that I'm disgraceful, that apostates should be killed and that I'm going to hell.”

And, while she tells me that she’s never feared violence from her immediate family since coming out as ex-Muslim, she notes ‘this was probably the hardest and most hurtful aspect of my experience of honour: that ordinary loving parents could reject you based on what other people may or may not think or say.'

All of the women I’ve spoken to have experienced unspeakable and unfathomable trauma not only at a young age but also in their home environment, the space that many of us retreat to when we experience problems in our day to day lives. Surely it’s time that we stop using the word ‘honour’ killings to describe these acts? After all, there is no ‘honour’ in honour killing. It’s a misleading term.

“I think ‘shame’ killing is more appropriate,” Halima agrees. 'There is absolutely no honour in abusing and/or killing your child or spouse for trying to live their lives. To think that my parents cared more about honour than me having a childhood.'

It’s also high time we stopped pretending that this doesn’t happen in the UK? There is a day dedicated to victims of honour-based violence: Tuesday 14th July 2015 marked the first UK-wide memorial day for victims of so-called honour killings and has been held on the same day ever since. However, we should also find ways to support women who experience pressure, fear, shame and even abuse as a result of notions of honour. Historically this country’s Government doesn’t have a good record on this particular sort of violence against women.

The women I spoke to all now live in anonymity and to some extent, in fear of possible repercussions from their families and communities. However, as Seena says there is a payoff: 'the most important concept of my mind now is freedom to be myself, wherever that takes me. That’s beautiful, simplistic and a much healthier goal to aspire to for me.'

You Might Also Be Interested In:

8 Things That Happen When You're Young, British and Muslim In The Weeks Following A Terror Attack

Follow Salma on Twitter @its_me_salma

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.