My last name is Escobar and I am from Colombia. Before I went to Europe, I never considered this to be significant in any way. It was simply my last name and my nationality. During the 1980s and 1990s, like most people living in urban Colombia, I saw war every evening on TV. The war was broadcast on the news, when the reporter would mention the name of a new kidnapped person, a Minister or a presidential candidate who had been killed, a group of indigenous people who had fled their town because of the war. Sometimes they counted the number of casualties during a combat. It all happened far away from the city, deep in the jungle or up in the mountains.

The number of displaced people during the longest internal war in Latin America was constantly repeated in the newspapers, on the TV and radio. In fact, it still is, which is why I keep it in my mind: seven million.

The first bomb attributed to the drug cartels exploded in 1985. A car full of explosives blew up in front of the United States embassy. In 1989 a truck full of explosives killed 63 people in front of the Security Department. That was one of the worst I remember. But more were to come during those decades, one in a social club, another one in a mall. For a teenager accustomed to this madness, a bomb exploding in a mall meant you couldn't go out that night. Reality used to look like something adults were too stressed about. Adults who only talked about politics, the exact kind of adult you would become one day without knowing it.

It was the early nineties when I went to Europe. As a young Colombian woman, I stopped counting the number of times I was asked if I was Pablo Escobar's niece or daughter. To travel during my adolescence was to feel constantly misunderstood. People thought they knew a lot about you, but they didn't. Any new acquaintance would ask if I did a lot of cocaine (I’d never done it), if there were many shootings in my neighborhood, if marijuana was everywhere, if my family was in the drug business. I felt like an alien and wished I could melt into invisibility. I felt that when I said my name and origin people started watching cartoons in their heads, cartoons in which I lived a parody of a crazy life in a crazy far off land.

After months crisscrossing European cities, spending time in seemingly endless green public parks, walking safely without constantly watching my back, forgetting traffic stress, pedestrian stress and the stress of being robbed, I went back home. There were no shootings in my neighborhood but still, daily life had an intense, nearly maniacal rhythm.

I was already fifteen but many of my friends were just reaching that important age. In Colombia, tradition dictates that the age of fifteen is when you ‘become a lady’. Tradition dictates that you throw a huge party, dress in a velvet or silk princess dress and your first pair of high heels, and dance the waltz with your father at midnight. This ‘coming of age’ event is one of the first institutions where status in Colombia is clearly displayed. I remember going to all kinds of fifteenth birthday parties. A few had a buffet table featuring a swan carved from ice. At one of them there was a swing on which the fifteen-year-old sat and rocked under a strong artificial white spotlight, around her a hundred people standing by and admiring the ‘new woman’ as she swung. When the girl stopped swinging, the father came to her and switched her flat shoe to a high heel as a symbol of her entry into ‘a new era’. Then came the waltz. All the men were in tuxedos, even though these men were mostly 14 to 16 years old. The wealthier the parents, the more extravagant the reception.

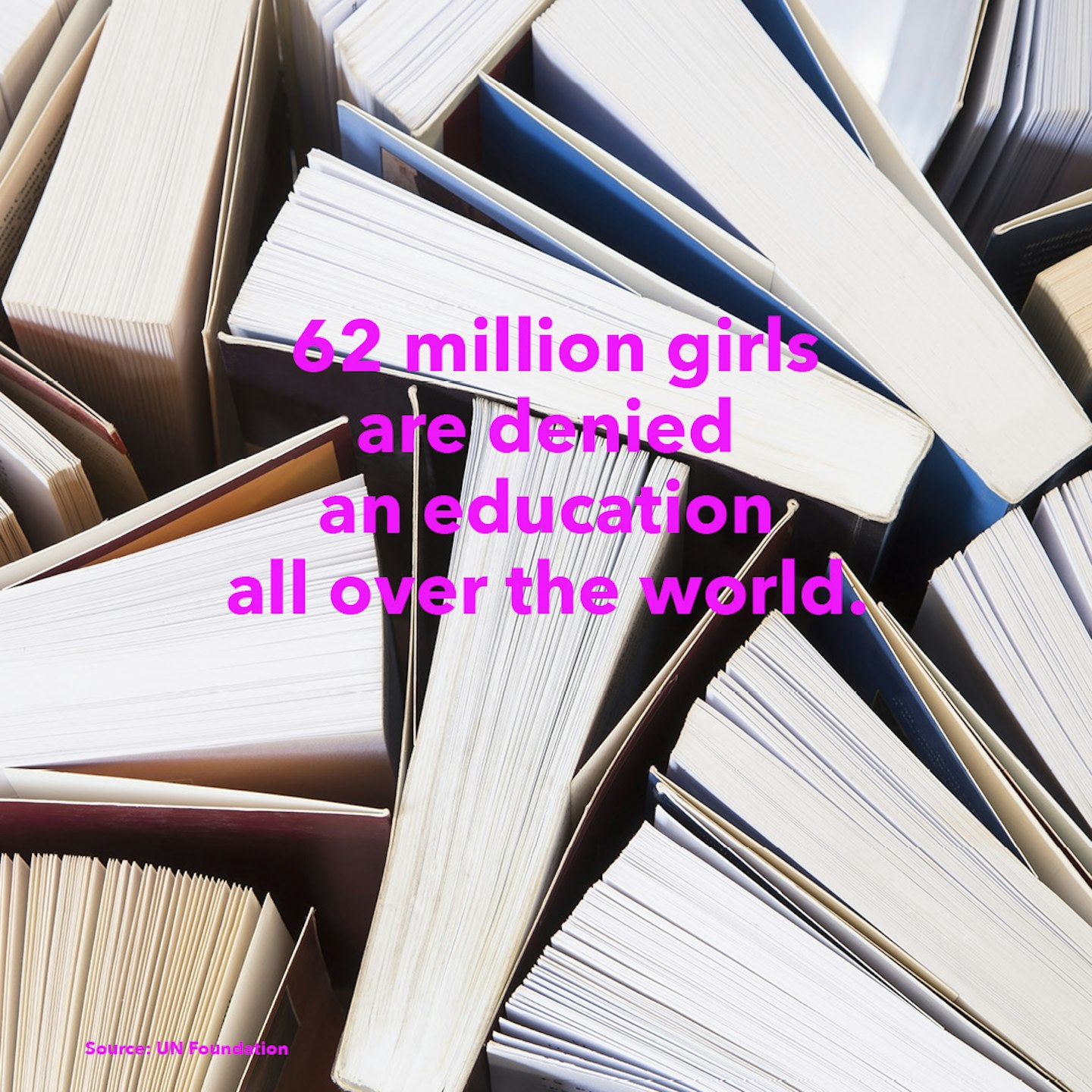

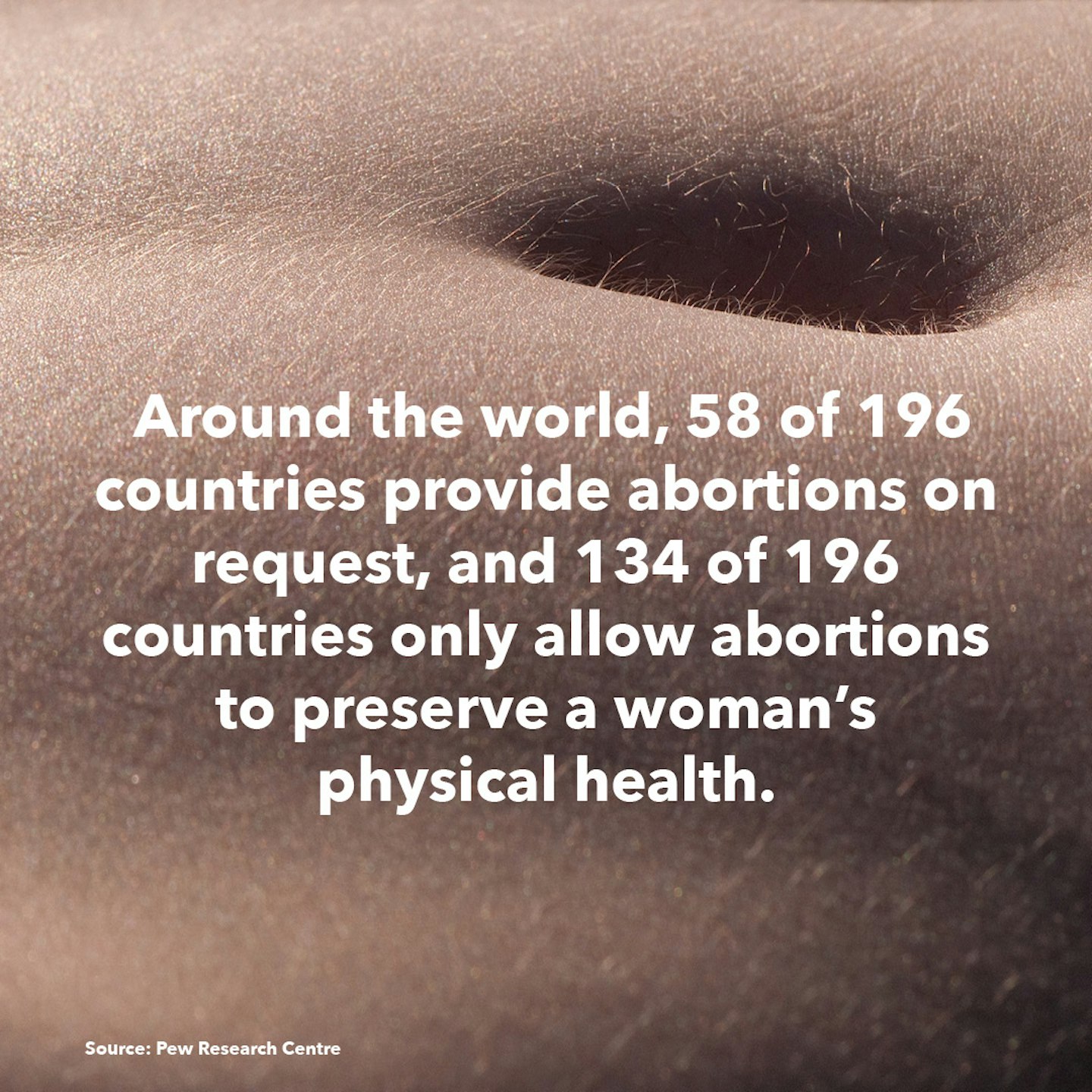

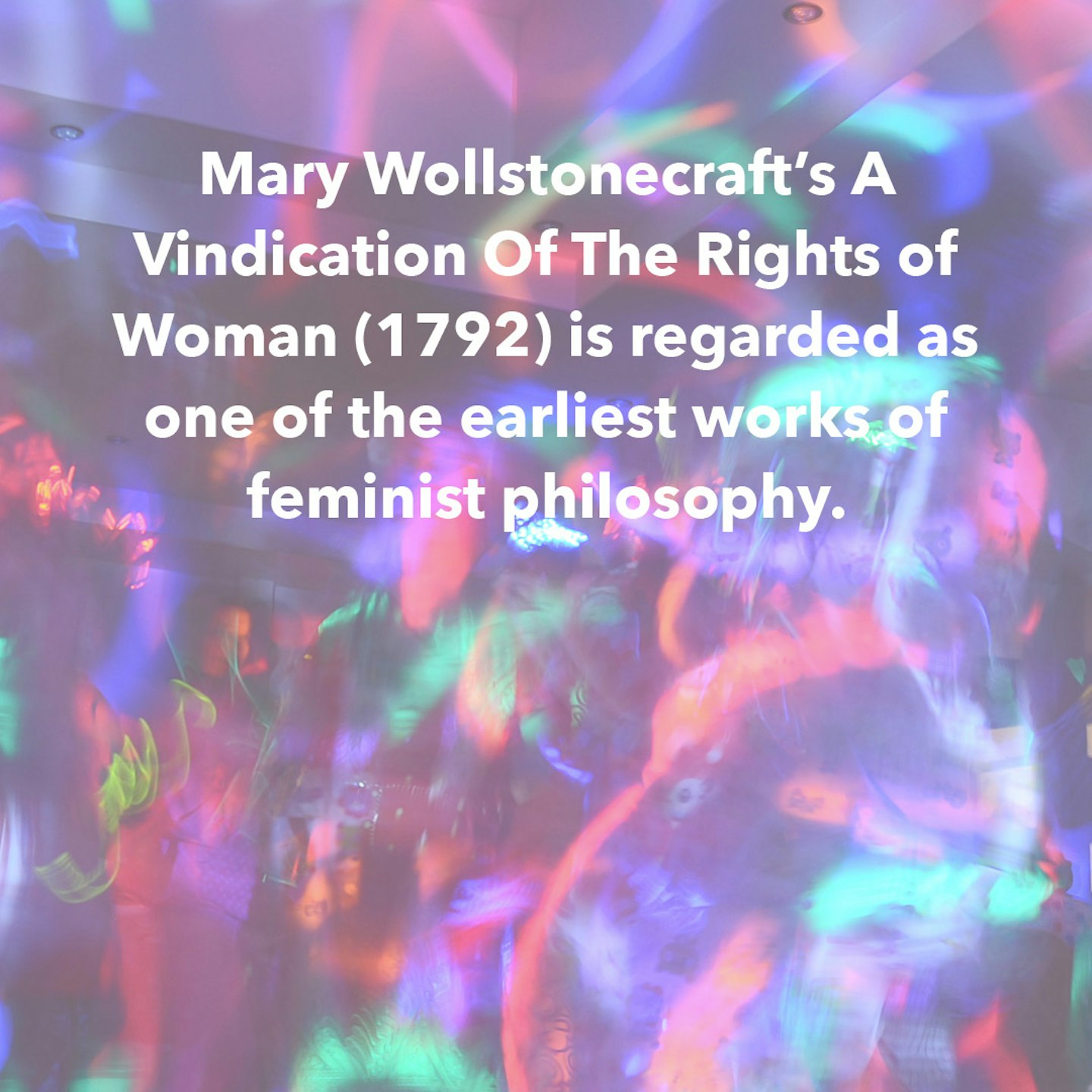

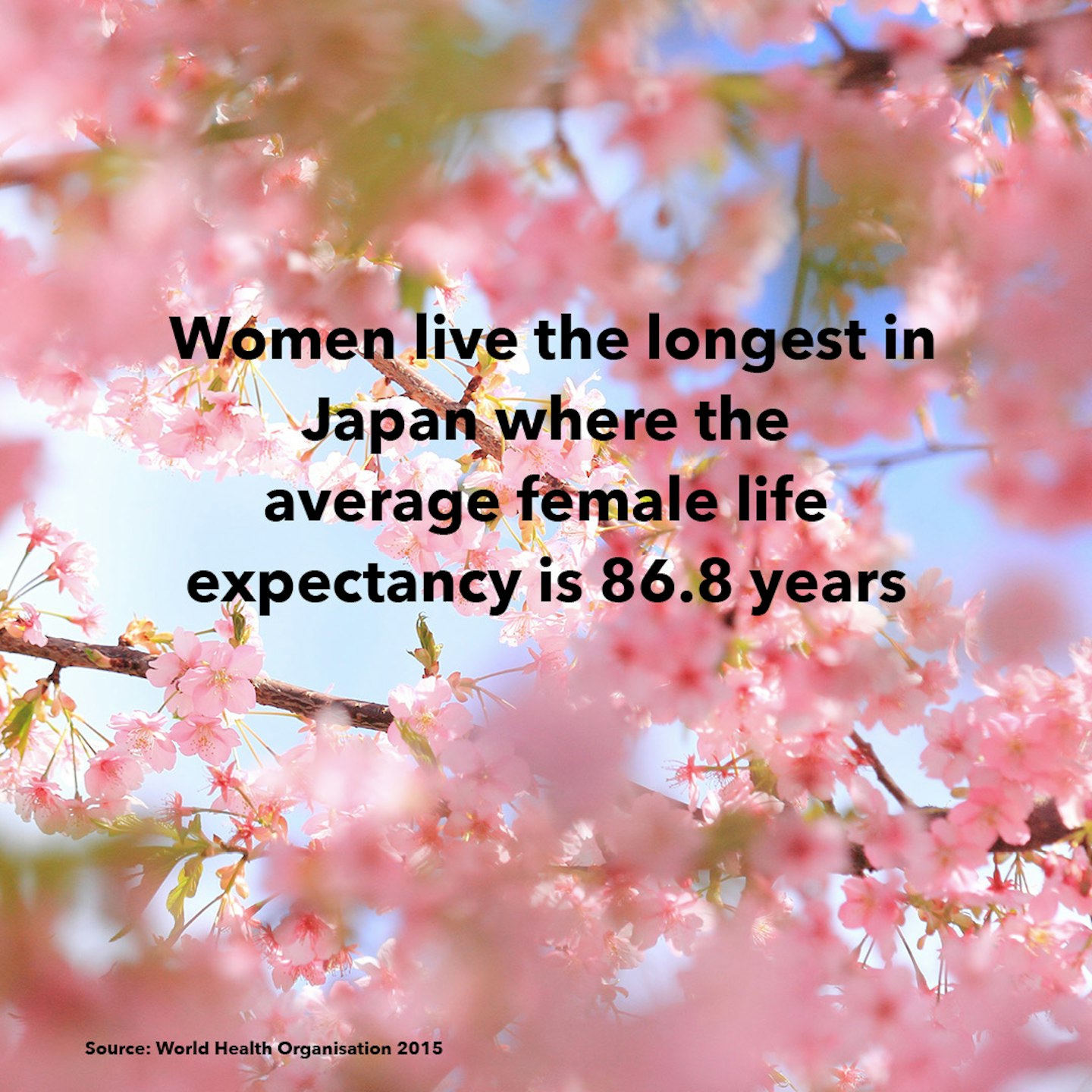

**READ MORE: Facts About Women Around The World **

Debrief Facts about women around the world

1 of 18

1 of 18Facts about women around the world

2 of 18

2 of 18Facts about women around the world

3 of 18

3 of 18Facts about women around the world

4 of 18

4 of 18Facts about women around the world

5 of 18

5 of 18Facts about women around the world

6 of 18

6 of 18Facts about women around the world

7 of 18

7 of 18Facts about women around the world

8 of 18

8 of 18Facts about women around the world

9 of 18

9 of 18Facts about women around the world

10 of 18

10 of 18Facts about women around the world

11 of 18

11 of 18Facts about women around the world

12 of 18

12 of 18Facts about women around the world

13 of 18

13 of 18Facts about women around the world

14 of 18

14 of 18Facts about women around the world

15 of 18

15 of 18Facts about women around the world

16 of 18

16 of 18Facts about women around the world

17 of 18

17 of 18Facts about women around the world

18 of 18

18 of 18Facts about women around the world

This celebration of the arrival at adulthood (or the age of procreation, more specifically) makes me think of the childhood stories of my childhood. Cinderella, Rapunzel, Sleeping Beauty, Beauty and the Beast: they were fifteen, sixteen at the most, when they chose their prince. Or, to be more accurate, when their prince choses them.

In an archaic model of western culture, women are taught to be liked, to be chosen, to be protected and to be loved. The passivity of this role still strikes me as a clear example of a sexist society. Why couldn’t we be the ones to choose, to protect, to like or to love? Why were we supposed to wait for things to happen to us instead of making them happen?

I had had a boyfriend for almost one year. I had chosen him. I took him to the movies, I gave him flowers, I kissed him for the first time, I visited him at his house and I decided when it was the right time for us to make love. Fairy tales did not work for me, neither did a culture of obedience in women.

I never thought, for a minute, that I was being the man in our relationship. I was just being me. But after that Sunday night when I lost my virginity, he went to school and told everybody he had now accomplished his goal after nine months of courtship because he had had me and I was no longer a girl because he made me a woman. Mission accomplished, end of story. For some months it was tough to see these kids talking behind my back. My ‘boyfriend’ never talked to me again. At least, he didn’t say a word during two years, and then he came to tell me he was sorry. He said he hadn’t meant to hurt my feelings by telling everyone about us, he just wanted to be a man in a man´s world.

I understood what he meant. A macho society, I know, is also cruel to men. I told him he had probably felt uncomfortable with a woman leading the way and wanted to prove somehow that he was the man by being in charge. He wanted me back; I did not want to be with him anymore. That was the end of a sad story but then, what is my public exposure in a country where three women complain of sexual abuse every hour? And they, it is estimated, represent only 20% of the actual victims. In 2017, Colombia had 567 victims of femicide and that was even with the peace agreement signed in June 2017 between the government and the Farc.

We still have a long way to go, indeed. Even though Pablo Escobar is dead and peace agreements have been signed, we deal with a history of war and chauvinism that is present in our daily life. Even for a woman like me, who has had the privilege, as very few people in my country do, of obtaining higher education, and having a comfortable life, these two harms are present all the time in my personal story.

My way of finding a place for me (and hopefully for many other women) was to write our version of the story. What is it like to be a woman in a man´s world? How does it feel to be invisible and condescended to? What hasn’t been told from our side of the story? To deal with these questions fully, we’ll need many more books in the future.

*Melba Escobar lives in Bogota. Her novel House of Beauty, is out now published by 4th Estate *

Follow Melba on Twitter @melbaes

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.