Something is happening. It's prickly, awkward at times, exciting and frustrating in equal measure and terrifying too. It started long before #MeToo or even the election of Trump in the US, in the likes of a nascent Everyday Sexism movement, but this two-syllable hashtag has undeniably acted like fly paper for sexism.

It is, at this point, hackneyed cliché to point out what a coincidence it is that such an international calling out of sexism and sexual harassment has come to a head in the same year that Britain celebrates 100 years since women were allowed to have a say in our democracy for the first time. The suffragette centenary marked the beginning of a century of change; as we enter the next 100 years of women existing in the work place and in public life, it's clear that we're about to live through a whole lot more.

Wherever there is progress, however, you can be sure that there will be a backlash. This thing, whatever it is, has gone too far, they say. More than half of women in the UK say that they have been sexually harassed at some point in their career, reported rapes in England and Wales have doubled in the last four yearswhile only one in every 14 reported rapes ends with a conviction, women - especially BME women - are paid less than men and the number of women in our politics doesn't not proportionally represent the number of women in our society but, never mind, they are uncomfortable.

They are, by and large but not exclusively, men. Sometimes they surprise you in their opposition to #MeToo and the fightback against sexism it represents because they aren't people you'd ever actually had to quietly file away under 'misogynist'.

Take Matthew Parris. Last week, the former Conservative MP and Times columnist appeared on Radio 4's Today Programme after he wrote an article for The Spectator in which he complained that Today's coverage of the centenary of women being granted the vote had 'seemed' to be 'all about women'.

Parris went on to say he felt that men 'almost feel assailed as a sex' because, as he sees it, an increasing amount of air time is being given to women and so-called 'women's issues'. I say 'so-called' because many would argue that gender inequality is also bad for men but, hey, that's another article.

Trying to articulate what exactly it was about the BBC's centenary of women's suffrage programming that so affronted him, Parris said: 'there were programmes about who's your favourite woman from the past, programmes about harassment, about women and I agree with all of it, I'm on the right side of this. I agreed with every word, I'm totally politically correct but it just all got a bit relentless'.

Luckily, Parris was debating former Equalities Minister and current Deputy Leader of the Liberal Democrats who, in her response, gave us all a masterclass in how to respond to sexism and mansplaining.

Ever so calmly, Swinson said 'that's the way we are used to the media and the world being, where men are the default, where men are twice as likely to be seen on screen at the cinema as women'. She added that perhaps this was 'uncomfortable for men because that is challenging a privilege and a dominance that [they] have gotten used to'.

Swinson made the point that, historically, women's achievements have gone unnoticed and that, despite the progress we have made, it is important not to be complacent about equality. Parris fell back on a lazy argument which sets women and men's equality up as a battle. Women, he said, are 'winning' to the detriment of men.

'Some of us, quite a few of us' Parris said, 'are reasonably enlightened and most of us would accept that in the past there has been this bias against giving women equal positions in society and on the media and all the rest, but it really is changing'.

Parris' reductive and facile line of argument will be familiar to many women. It speaks to the old adage: when you're accustomed to privilege, equality feels like oppression.

The Debrief spoke to Jo Swinson, who has also recently written a book - Equal Power and How You Can Make It Happen - and asked her about the importance of challenging those we disagree with and staying calm and collected when faced with a self-righteous mansplainer.

Part of the problem we currently face, Swinson says, is that we've come so far but it isn't far enough. 'As I write in my book, it's easier to get from zero to 25% [representation] than it is from 25% to 50% because men go "oh there are no women here so that's clearly wrong" but once women are there, they think they've sorted it out'. I ask whether part of the problem is that some men really do feel that things have now gone 'far enough'? Swinson agrees, 'to get to 25% men are saying "we're inviting women to join our club, but you have to play by our rules" but, to get to 50% we're saying that we need to completely rewrite the rules and that threatens dominance and power'. That, she says, 'is why [someone like Parris] who feels they are right on might be feeling uncomfortable.'

This, in and of itself, underlines the importance of debate. Swinson says 'we do need space to talk about this…not so that men can be defensive about it but so that we can present the case for more progress'. For instance, she points out, 'when a man walks into a room full of women they almost always make a joke about it because they're suddenly aware of their gender but what they don't understand is that women are used to being in a minority - the only woman in the room, the boardroom, the broadcast suite or whatever…'

The issue, Swinson says, it what people are benchmarking equality against. Parris might feel, as he said on Today, that women have 'won' and continue to 'win all the time' but that's in the context of his lifetime and how far things have come. Just because more women now have powerful jobs than they did when he was a child doesn't mean women have 'won'. 'I remember watching a debate in Parliament about family-friendly working hours' Swinson says ' and the issue of the diversity of parliament came up. This guy was speaking - a Conservative - one of his woman colleagues interrupted and said parliament is overwhelmingly dominated by men. He replied there are a lot more women than there were here before. I went away and did the maths: two thirds of MPs are white men but they only make up 43% of the population, but this guy couldn't see that this was unequal because when he became an MP things were very different. He was benchmarking against how it was 20 years ago, it might look like women are winning but if you benchmark against true 50:50 equality and not the past then we're nowhere near winning'.

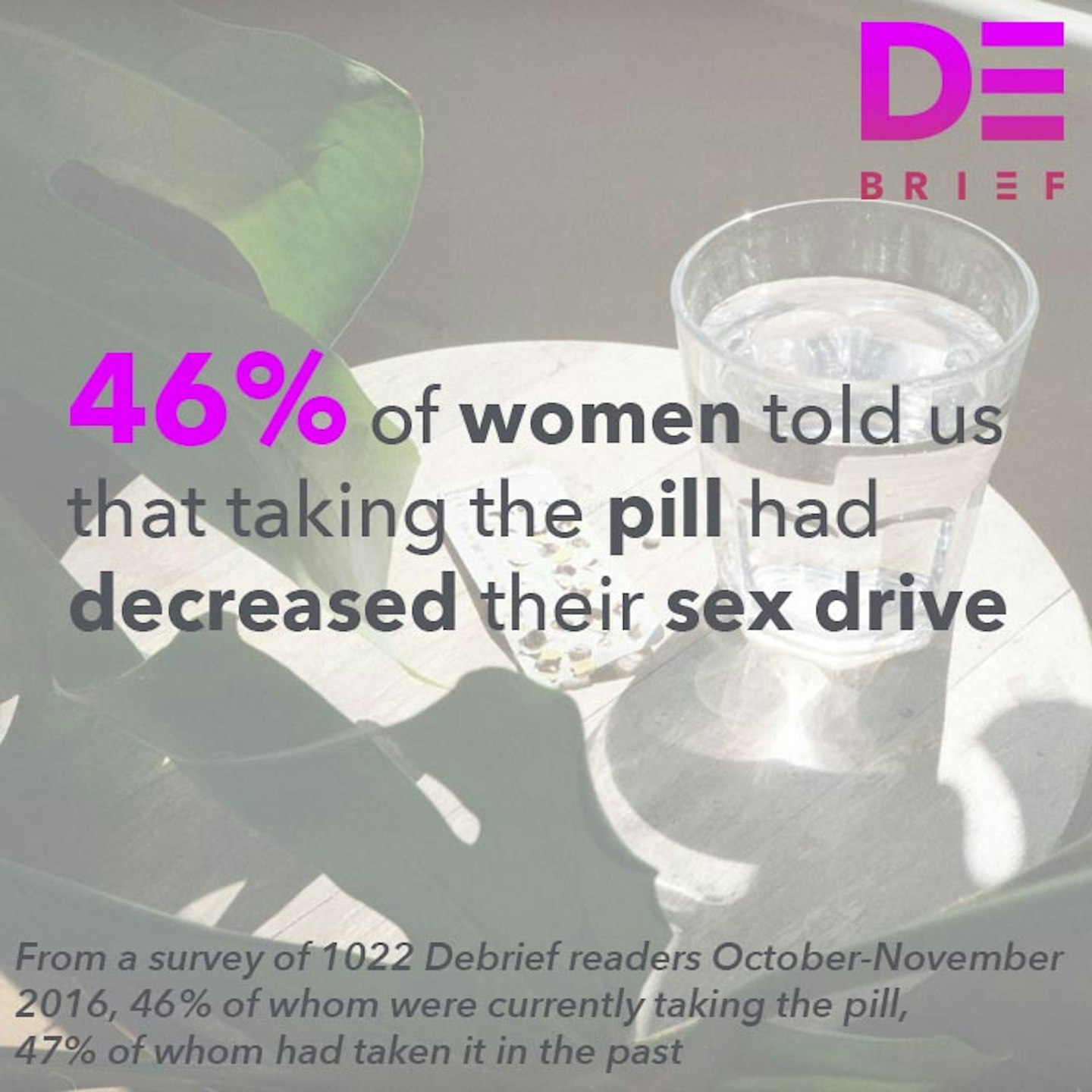

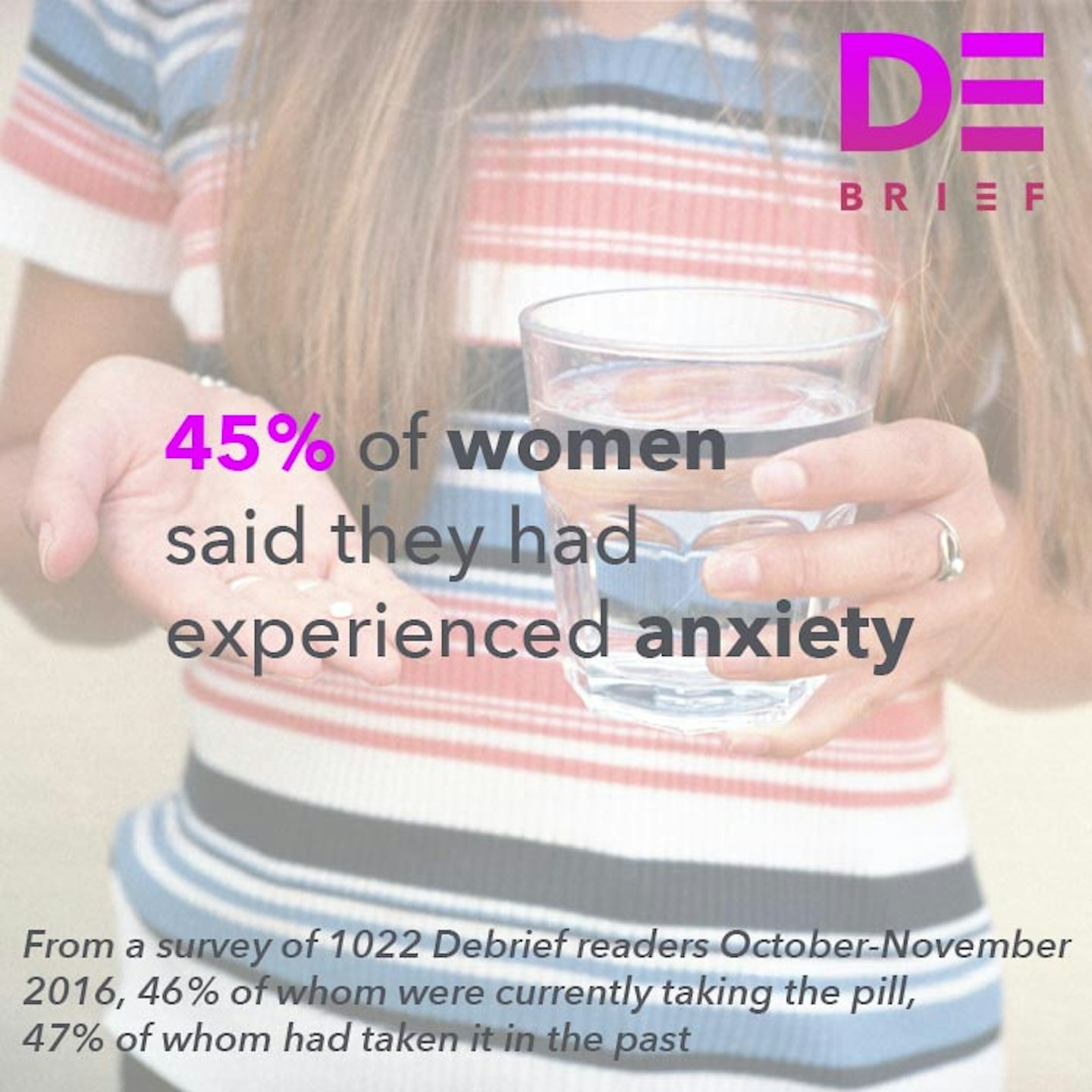

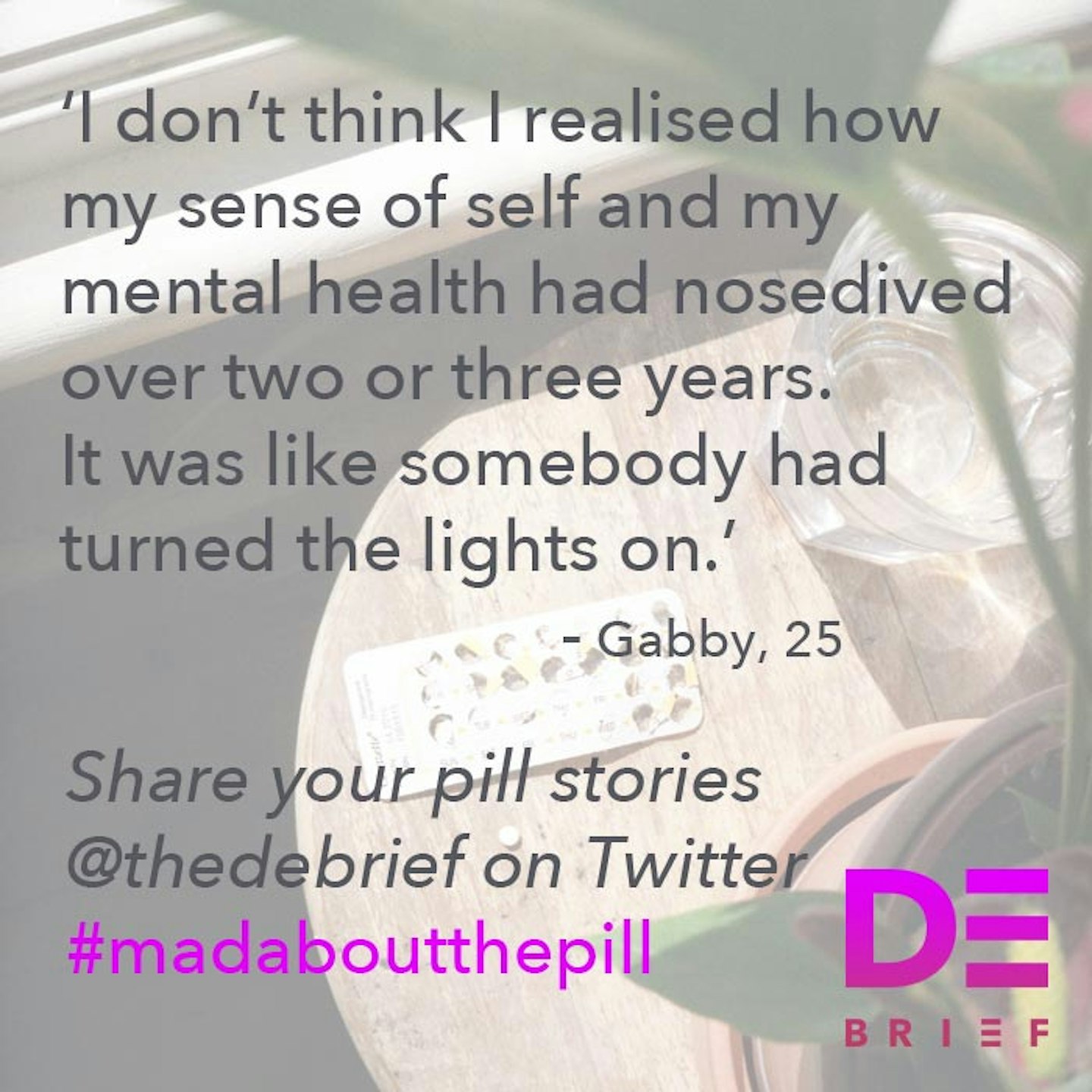

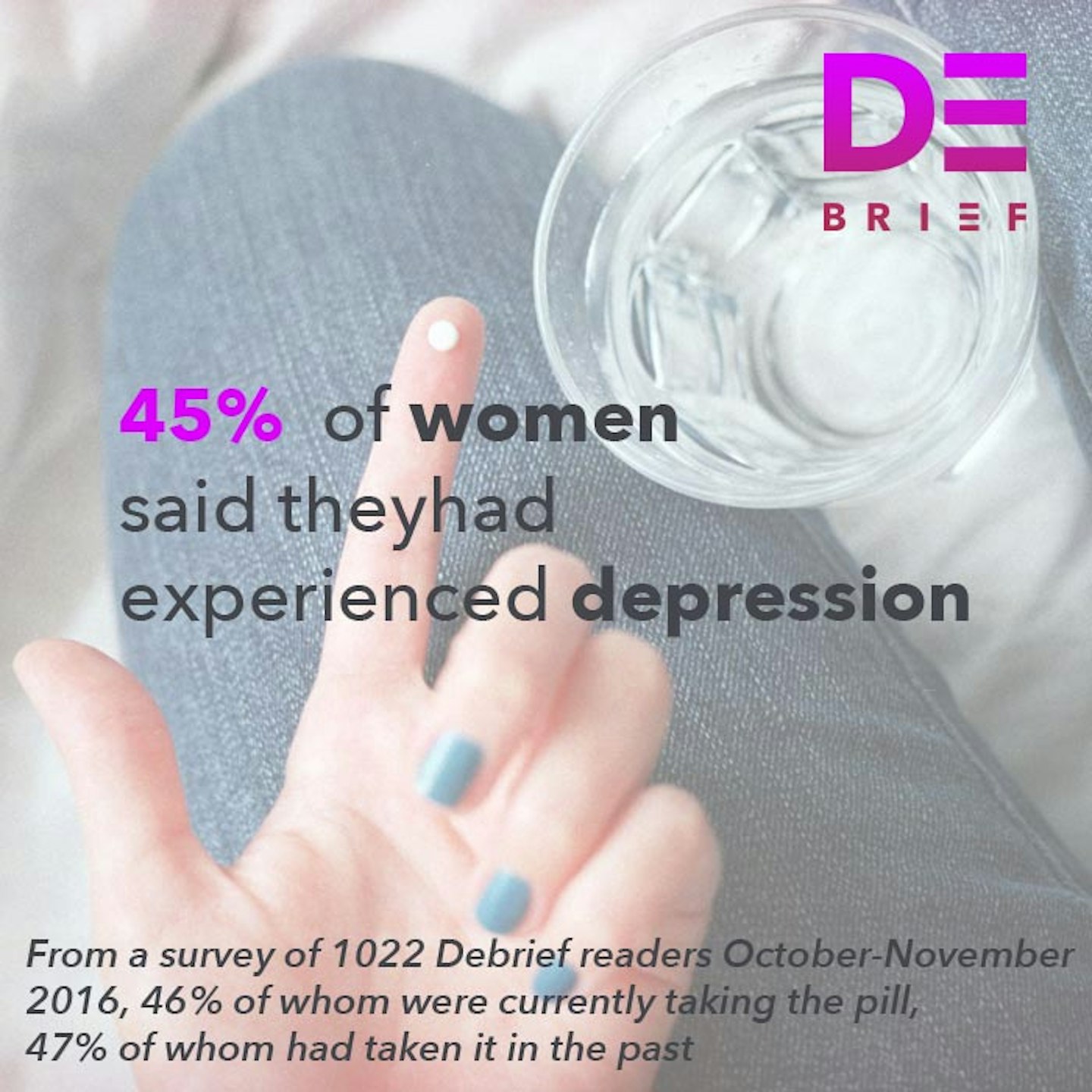

**READ MORE: The Debrief Investigates - Hormonal Contraception And Mental Health **

Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

1 of 9

1 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

2 of 9

2 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

3 of 9

3 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

4 of 9

4 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

5 of 9

5 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

6 of 9

6 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

7 of 9

7 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

8 of 9

8 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

9 of 9

9 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

Is part of the problem, I ask, the Twitterfication of debate. Everything is only good and bad, right and wrong and never nuanced or complicated. Sometimes this discourages us from seeing disagreement as an opportunity for discussion and, ultimately, learning. 'It is hard' Swinson agrees 'in our Twitter age…in this very polarised time where everything is painted in a very extreme light. It's made to seem as though it's one thing or its polar opposite but there has to be space for learning'. The truth is that the continuing fight for true equality between men and women is not, as Parris kept suggesting, about 'winning'. Women's equality will not be 'won' at the expense of men because a truly equal society will benefit us all.

A good example for the benefits of creating space for learning as opposed to polarising opposition, Swinson tells me was the impact of Renni Eddo-Lodge's book Why I'm No Longer Talking To White People About Race. After reading it, she says she is 'much more aware of the privilege' she has 'as a white skinned person'. Reading the book did not make her defensive or protective of her privilege but instead made her think 'oh my goodness have I been blind to injustice'. She explains 'in the same way that I've not experienced [racial] discrimination or discrimination about my sexual orientation, I have to listen and learn to people who have and realise that privilege - it's similar for men - they might get it, or they might not get it, but they want to - we need to speak with them, so they can learn - this is what I suggest in my book - talking to your male friends and colleagues about your experiences'. Even individual conversations within a personal circle of trust can be powerful, she says in helping people to understand power dynamics because 'when it's your friend, sister or daughter telling you it's harder to dismiss and easier to understand.'

I tell Swinson that I have tried to practice this when male friends make rape jokes or try to belittle conversations about sexual harassment. Instead of allowing my anger to boil over, I now ask them whether they've ever feared for their safety while walking home or worried about going to a work event because of what a colleague might do after a few drinks? 'Exactly' Swinson says 'when Matthew Parris was talking about the unwanted advances he experienced from a woman [on Today] I wanted to say, "but did you fear for your safety Matthew because women in sexual harassment situations feel vulnerable for their safety". The problem arises when men try to do the equalising thing' she says, and suggest that their experience can be directly equated with a woman. What they're not realising, Swinson points out is that 'they can rebuff the advances in a way that won't necessarily lead to violence against their person - but I understand that when men haven't experienced that they might not be able to put themselves in those shoes.'

Rather than shut down debate, Swinson says 'we need to give men and women space to acknowledge that we were all brought up in a sexist culture. We have all absorbed sexism from that culture because it has been there every day in the conversations we've had since we were toddlers about men and women's roles which have been reinforced over and over again. When people say they don't see gender or race, the truth is that they're biased to their own prejudice - so you need to give people the space to realise that they have bias'.

It's exhausting to realise the extent of the emotional labour that women are still doing to overcome inequality. However, perhaps this labour is not going to be carried out in vain? Swinson says this is why she wanted to write a book which talks about how we reach equality 'in practical terms'. In talking about it, she says, 'we can move things on'.

And move things on we must. The truth is that #MeToo and the conversations it has fuelled have hardly gone too far, they've not gone far enough. The fact that people feel they have gone too far is testament to how far we still have to go. 'Remember 4 or 5 years ago when Emma Watson gave her speech to the UN' Swinson says when I say this 'she was still having to explain why she considered herself a feminist then but now there is energy and momentum in the movement and I think some men feel a sense of they don't know what's next so they feel a sense of a lack of control especially when it comes to sexual harassment stuff.' Feminism is well and truly mainstream now and change is uncomfortable, particularly for those whose previously unchallenged privilege is under threat.

I ask Swinson if she thinks men are right to feel threatened? 'I do I think men's privilege is under threat and that is part of the point of the #MeToo movement, but I do also believe gender equality is better for men and women alike. Inequality also harms men. Take masculinity and mental illness - suicide is top killer of men, men's role as fathers is constantly undermined - they are characterized as incompetent at home in same way women are in the work place - but at the same time you can't get away from the fact that people still assume a man is competent when he opens his mouth simply because of the fact that he is a man and we do want to do away with that.'

Ultimately, Swinson's message is one of making space for debate and discussion, not just for opposition. 'I suspect there's a combination of men out there' she says 'those who do respect women and feel that [their good behaviour] isn't being recognised. Sometimes they are mistaken in the extent to which they are advocates for equality or perhaps they're patronising in their approach to gender equality and don't realise'.

Something is changing. Power is shifting. #MeToo is and has always been about telling difficult stories and having uncomfortable conversations, stories that are sometimes ugly and conversations that are sometimes complicated. Hearing them isn't easy and unthreading them so that we can make sense of them is ever harder, but having the conversations they spark is what the movement is for. Where it leads us to remains to be seen.

In the meantime, Swinson's example of feminism in practice is one we can all learn from. She both undefensively acknowledges her own inherent inherited privilege as a white feminist and is prepared to allow those who disagree with her the space to realise theirs. 'Some men' she says 'are not sure what the rules of engagement are because the rules they were bought up with are wrong. They're now being told that it's not ok to act in those ways and maybe they were taught by their brothers and fathers that this was how you treat women. They're having to relearn and about time too, frankly'.

Equal Power: And How You Can Make It Happen, By Jo Swinson MP is out now

Follow Vicky on Twitter @Victoria_Spratt

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.