There are many things that define your first girls' holiday. It might be the significance of the destination you go to, a holiday romance, or even getting into a drunken argument with your best friends.

My first girls' holiday was defined by two things or, more accurately, two conversations. The first was with a shop assistant. I was buying some swimwear and we exchanged pleasantries which, eventually, led to the question of where are you going on holiday? 'Miami', I responded. 'Just make sure you don't tan too much' she said. She didn't have to utter another word. I knew exactly what she meant. I was black enough and becoming blacker would make me less attractive. What had been a light and polite conversation came to a grinding halt and I hurried off to pay for my swimsuits.

The second happened once I'd touched down in Miami. I was talking to a guy and he suddenly said, 'you're quite pretty for a dark-skinned girl'. He genuinely believed it was a compliment. He thought that I should be grateful to be deemed attractive, not because of but in spite of my skin tone.

This is something I am sure many darker skinned black women have heard from a prospective love interest. It is a common line that is intended to remind us that the majority of darker skinned women aren't beautiful or deemed attractive unless they're 'lucky' enough to be seen as an exception to the rule.

This is colourism: prejudice or discrimination against individuals with a dark skin tone, typically among people of the same ethnic or racial group. Sometimes the preference for or pressure to be a lighter skin tone occurs within families. Elizabeth Morris (not her real name) says that she started using skin bleaching products as a child because her family would constantly praise actresses with fairer skin. ‚I was eight when I first used [skin lightening] creams' she tells The Debrief, 'I thought being light skinned was the standard [of beauty] and I, being dark skinned, deviated from this'.

Elizabeth recalls watching Nollywood (Nigeria's version of Hollywood) with her parents whenever a light-skinned actress would come on TV. 'My parents would say "oh the beautiful fair one" or "she's very fine, she's yellow" and the word beautiful, at least in my mind, became associated with women of a lighter complexion', she says.

Like, Elizabeth, Jemmar Samuels, also started using skin bleaching creams due to the pressure from family, as well as school friends. ‚I started bleaching my skin at the age of 13' she recalls, 'I felt because I was dark skinned I was ugly. I believed that I would be liked more and treated better if I was lighter, due to being bullied for my complexion in school'. For Jemmar the pressure also came from within her own family. 'Family members, such as cousins would tell me to start using a [skin lightening] cream just to "tone" my complexion and it was a constant reminder that I was "too dark",' she says, '[I knew] family members were going to keep reinforcing that idea until I fixed it. So, I genuinely felt my life would be easier if I "corrected" the colour of my skin'.

Colourism, the preference for lighter skin and discrimination against those with darker skin, is often presented like this: as a problem to be fixed. Of course, that's wrong on so many levels. Within the black community this has been an ongoing conversation for some time but, recently, it went more mainstream when Mathew Knowles, Beyoncé's father and former manager, questioned how successful Beyoncé would have been if she had a darker complexion during an interview withEbony. In the interview, he also said that 'internalised colourism' led him to his former wife, Tina Knowles, because he 'thought she was white' when they first met.

'When it comes to Black females, who are the people who get their music played on pop radio?' Knowles told Ebony, 'Mariah Carey, Rihanna, the female rapper Nicki Minaj, my kids [Beyoncé and Solange], and what do they all have in common?'

While we might not like what Mathew Knowles said, it is difficult to name a darker skinned black female musician who has had a similar level of success to those he cited. The difficult truth is this: the music industry and the entertainment world as a whole, has played a crucial part in creating and upholding an acceptable face of black womanhood- a black woman with visible white ancestry.

Furthermore, RnB and Hip-Hop music videos have played their part in devaluing the worth of darker skinned women. Many RnB and Hip-Hop videos usually feature lighter skinned black women in positive and romantic lights, while darker skinned women are virtually invisible. This is something that is not lost on Elizabeth. '[The music industry] has most definitely contributed to the problem of colourism' she tells *The Debrief *'in music videos, for example, especially during my childhood, only light skinned models were used as dancers or love interests'.

This idea that Hip-Hop culture has always elevated black women of a lighter skin tone was made clear in the casting call for the 2015 film, Straight Outta Compton){href='https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Straight_Outta_Compton_(film)' target='_blank' rel='noopener noreferrer'}. The film's producers used a detailed ranking system when it came to casting female actresses in the film. Women were ranked in categories from A-D, with A girls being the hottest of the hottest, and could be 'black, white, Asian, Hispanic, Middle-Eastern, or mixed race too. Meanwhile, D girls were African American girls, who were described as poor, not in good shape and medium-to-dark skin tone.' The descriptions in each categories not only illustrate how black women have to deal with misogynoir, (a combined hatred of racism and sexism), but how black female bodies are inherently and unfairly seen as unattractive.

Hollywood has acknowledged its problem with race, the lack of leading roles and lack of accolades for black performers, but it still refuses to face up to the problem of colourism which is inescapably illustrated by the women who front Hollywood's young black feminist movement. Actresses Zendaya Coleman, Yara Shahadi and Amandla Stenberg have all lent their voices to important causes to combat racism and alongside their performances it has landed them Teen Vogue, Vogue, ASOS, Dazed and countless other magazine covers. Furthermore, due to their acting and activism, these young women have landed guest editor roles, beauty and fashion campaigns. But, we must be honest with ourselves and question if their talent and their commitment to challenging racial inequality are the only reasons why they have been able to break into mainstream media and front mainstream beauty and fashion campaigns.

In comparison, darker skinned actresses such as Keke Palmer and Michaela Coel who are just as talented and outspoken about race issues, haven't acquired nearly as many magazine covers, campaigns or column inches as their lighter skinned counterparts. With Zendaya, Yara and Amandla being the dominant voices and visible faces of the young black feminist movement, we cannot avoid what they have in common beyond their talent and activism: biracial heritage.

Beyond the entertainment industry, the beauty industry has also exacerbated the problem of colourism by upholding certain beauty standards. Cosmetic Scientist and MDMFlow founder Florence Adepoju explains that 'the mainstream beauty industry has shown a single view of beauty for a really long period of time'. She believes 'this contributes to colourism as dark skinned black women are rarely included in this narrative' and says, 'if they are, they are usually the odd one or two and are celebrated for having western features'. For Adepoju 'by refusing to celebrate the various forms and complexions of black beauty' the beauty industry has 'perpetuated the narrative that lighter skinned women are somehow inherently more beautiful'.

Historically, the limited and limiting idea of beauty portrayed by the cosmetic industry has not only endorsed colourism but been further cultivated by brands who refused to stock shades that go past sand and caramel colours. For this reason, it is hardly surprising that Rihanna's 40 shades of Fenty foundations caused complete pandemonium for all the right reasons or that seeing Duckie Thot and Lupita Nyong'o in major beauty campaigns feels so significant.

In order to move the conversation about colourism forward we must acknowledge that, like its cousin - racism, colourism is deeply ingrained within our institutions and structures. Ultimately, it is a legacy of slavery and colonialism. The trauma attached to both might be why some in the black community are reluctant to discuss the problem. The fact that it has taken Matthew Knowles (of all people) using the word to spark mainstream conversations is telling.

Social historian and broadcaster Emma Dabirisuggests an alternative reason as to why colour-ism is still such an open secret. 'There can be a sense that to focus too much on the shade of skin is divisive (yet this can also facilitate colourism becoming obscured)' she tells The Debrief. 'In addition,' she says 'if you take somewhere like the US in particular, you had a situation where very light skinned people- who might in fact only have one black grandparent and three white- were classified as black. They would live in black communities unless they passed [as white] and be treated as black according to the law'.

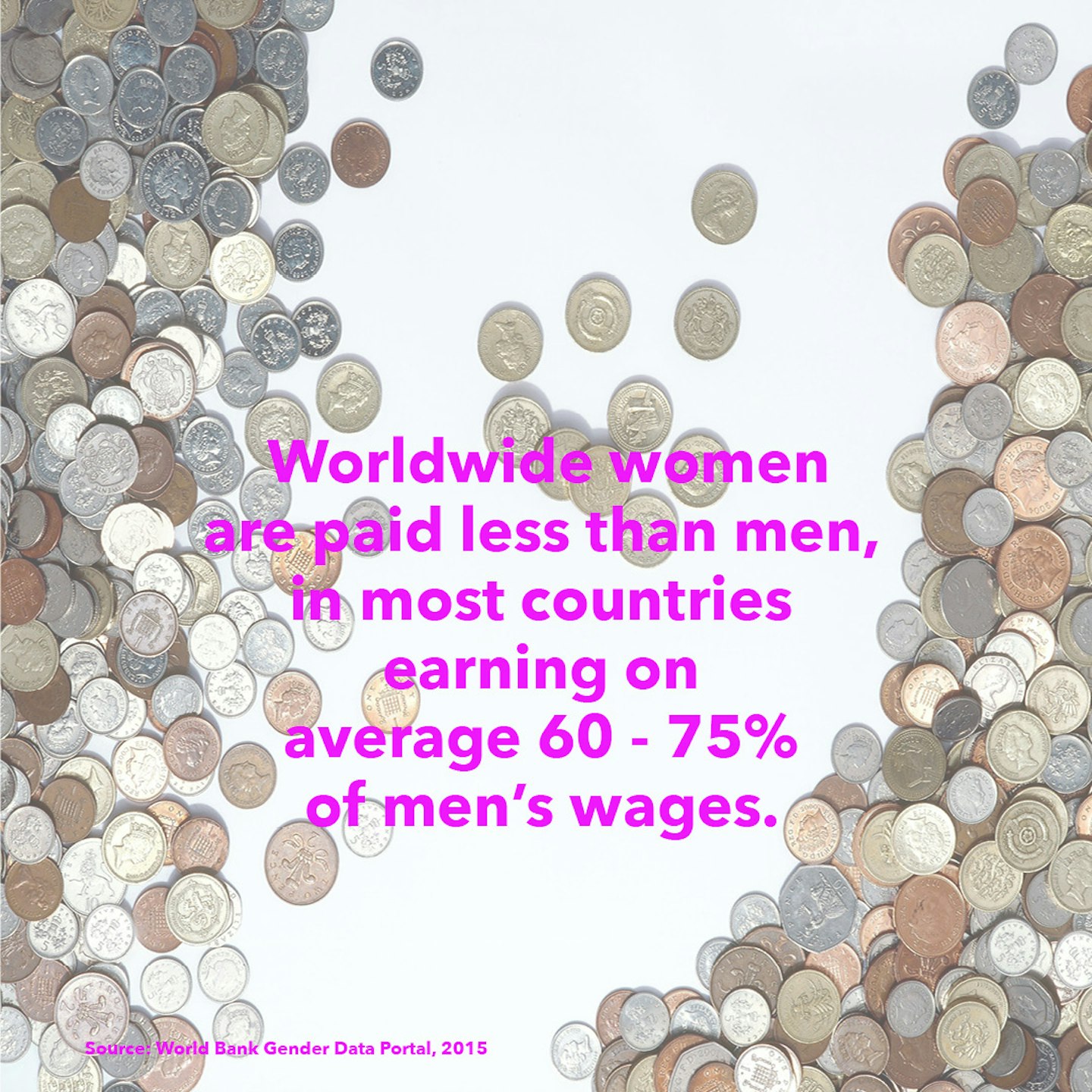

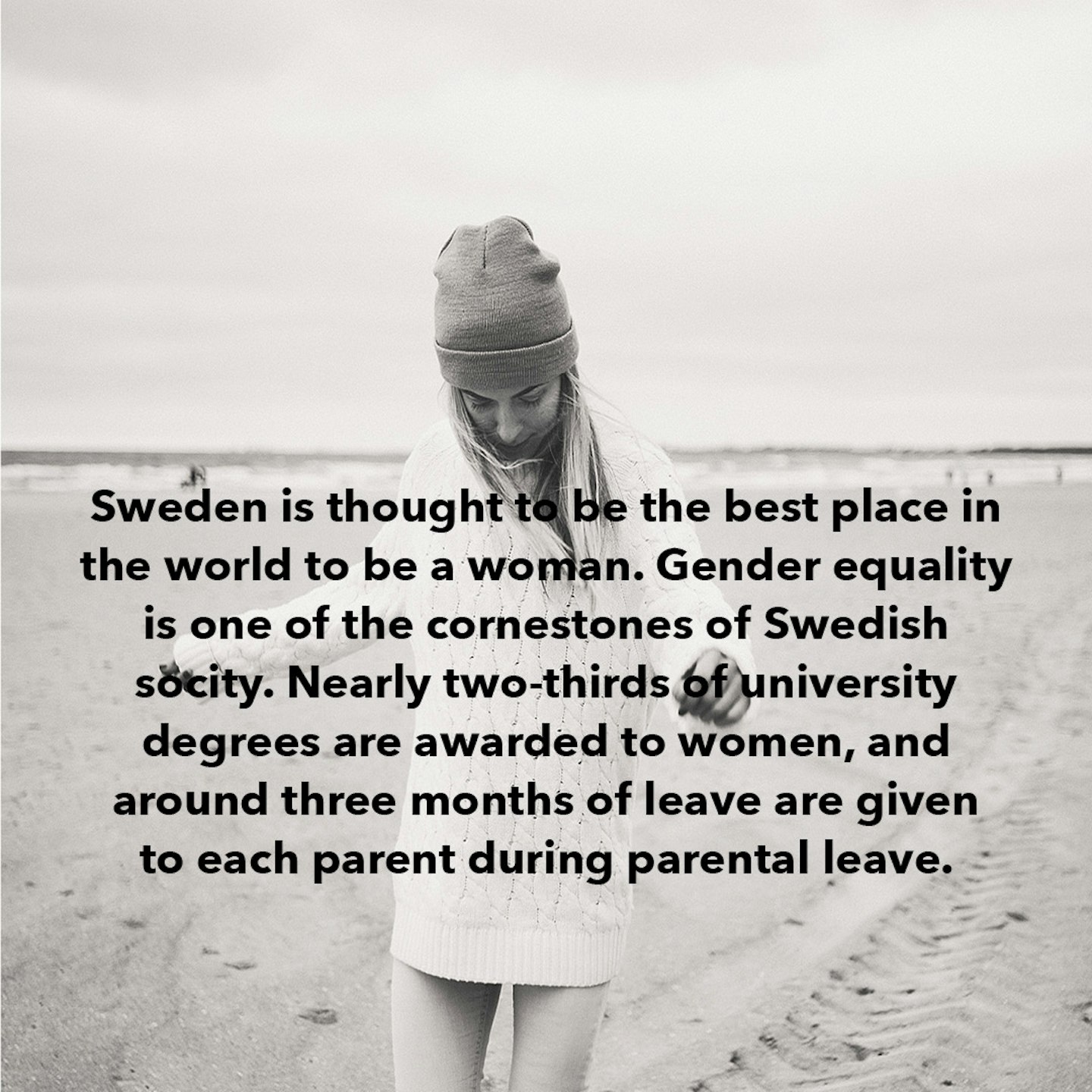

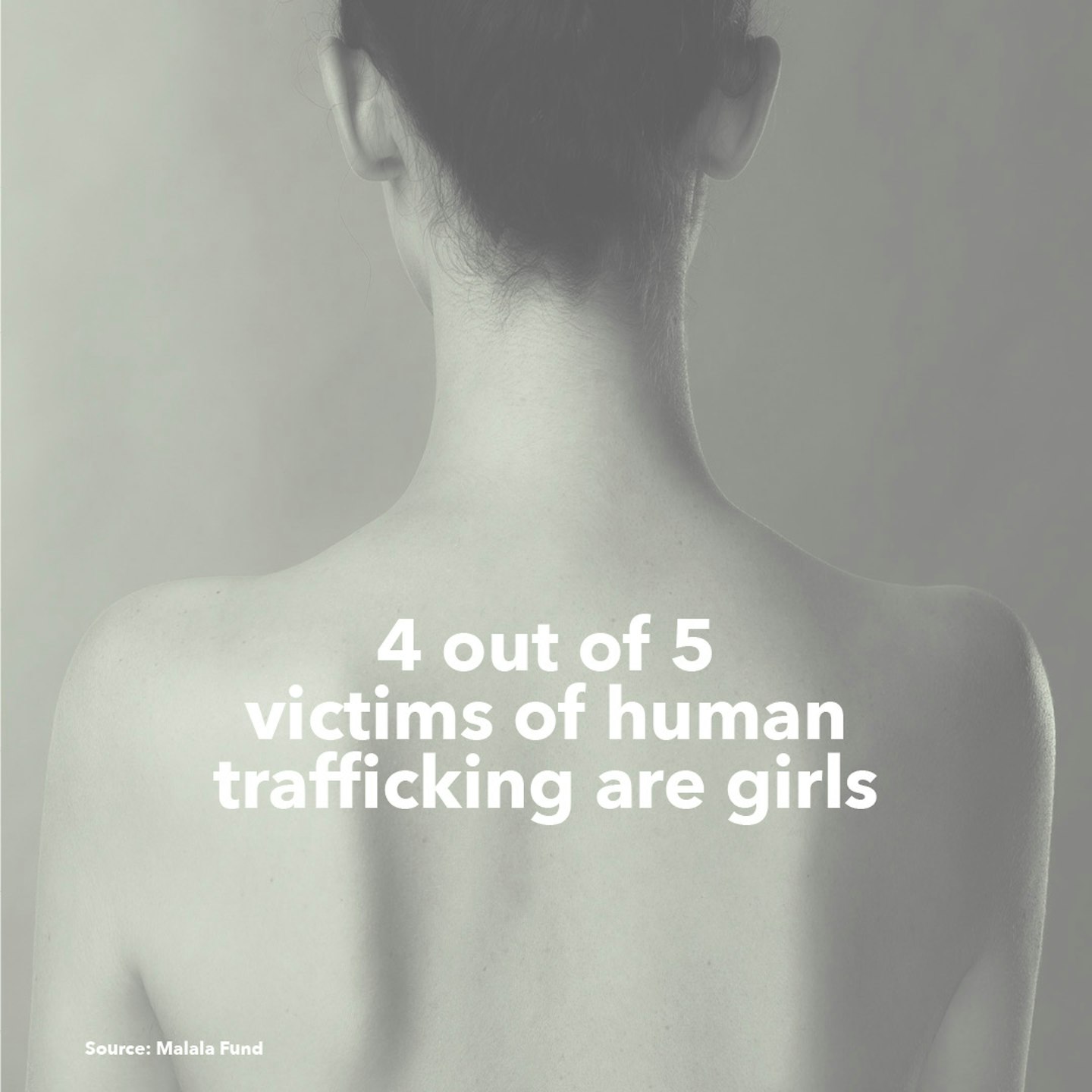

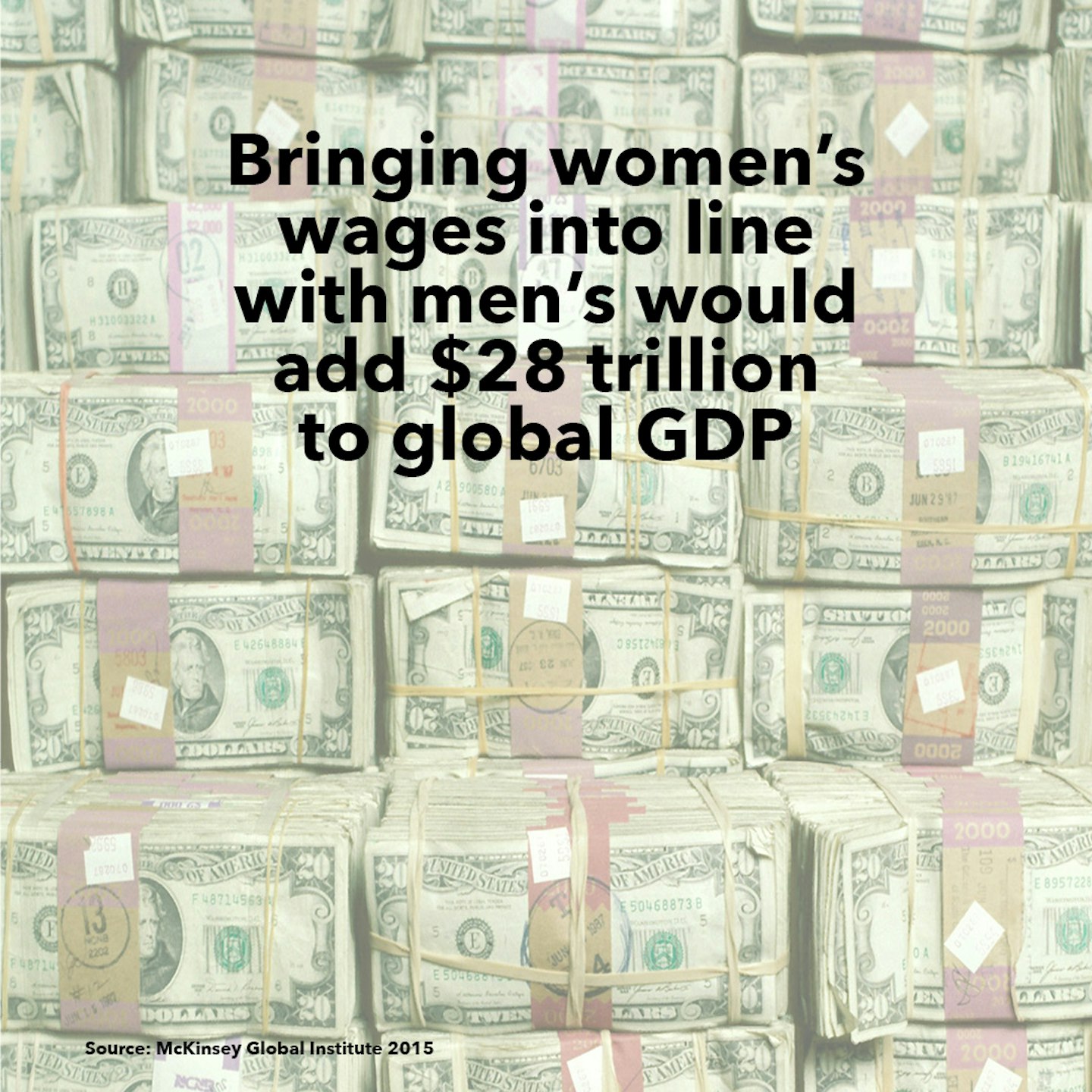

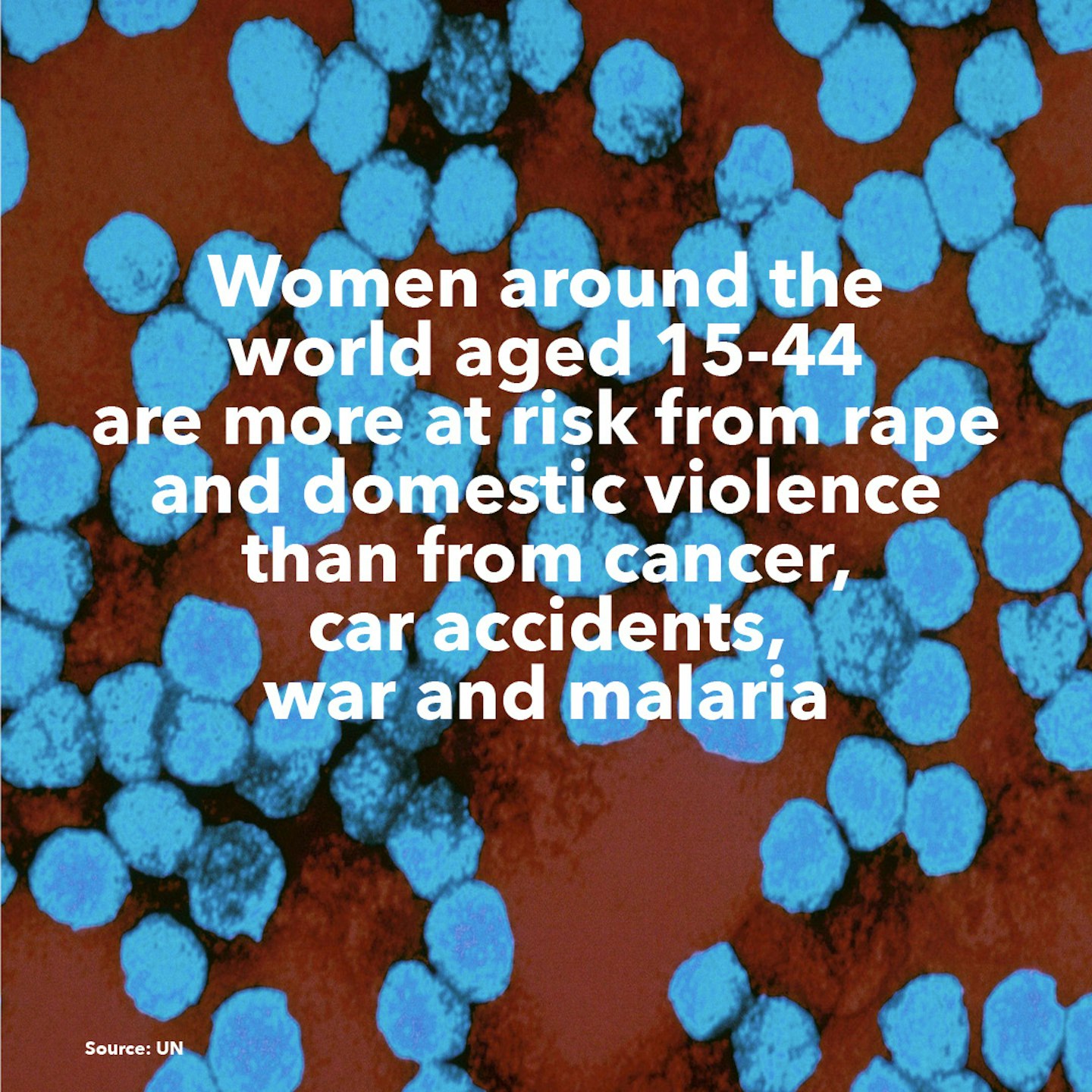

**READ MORE: Facts About Women Around The World **

Debrief Facts about women around the world

1 of 18

1 of 18Facts about women around the world

2 of 18

2 of 18Facts about women around the world

3 of 18

3 of 18Facts about women around the world

4 of 18

4 of 18Facts about women around the world

5 of 18

5 of 18Facts about women around the world

6 of 18

6 of 18Facts about women around the world

7 of 18

7 of 18Facts about women around the world

8 of 18

8 of 18Facts about women around the world

9 of 18

9 of 18Facts about women around the world

10 of 18

10 of 18Facts about women around the world

11 of 18

11 of 18Facts about women around the world

12 of 18

12 of 18Facts about women around the world

13 of 18

13 of 18Facts about women around the world

14 of 18

14 of 18Facts about women around the world

15 of 18

15 of 18Facts about women around the world

16 of 18

16 of 18Facts about women around the world

17 of 18

17 of 18Facts about women around the world

18 of 18

18 of 18Facts about women around the world

Emma also offers some insight into why colourism disproportionally affects black women, rather than black men. 'Colourism plays out differently across genders' she explains, 'because of the way racial categories have been constructed. Blackness has been constructed around characteristics associated with masculinity, being mixed [race] or light, [or] having longer, softer hair is associ-ated with more feminine features in the social construction of race'.

From not being able to buy foundation to family pressures to adhere to the beauty standards of whiteness, from the lack of diverse representations of black womanhood to overt discrimination and prejudice, colourism is an issue that dark skinned women battle day in, day out.

Forecasters are predicting that the skin lightening industry will be worth $23 billion dollars by 2020. It is clear that the weight black women feel to live up to whiter and lighter beauty standards is not only affecting black women globally but also big business. If we don't start discussing colourism alongside racism, this will continue to be the case.

All of this has to be why Black Panther has felt so necessary and long overdue. The film subverts all of the beauty standards that have been applied to black women. In having Lupita Nyong'o, a darker skinned woman with short afro hair, as the love interest and Danai Gurira, a bald dark skinned black woman, in a position of authority the film rewrites the status quo. The more we see black women not having to submit to Eurocentric beauty standards, the closer we will come to doing away with colourism.

We still have a long way to go. There's no doubt that all black women, regardless of their skin colour, experience racism but we are still not willing to admit that lighter skinned black women and their proximity to whiteness buys them social capital and privilege that dark skinned women do not possess.

*Names have been changed

Follow Tobi on Twitter @IamTobiOredein

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.