This is your weekly instalment of WTF is going on because, these days, a lot can happen in a week…

This week, the Internet has been awash with hot takes and mistakes when it comes to the coverage of an allegation made against_Master of None’s_Aziz Ansari. Initially reported onBabe.net, an anonymous 23-year-old woman going by the pseudonym of ‘Grace’ told her story of how Ansari had coerced her into a sexual encounter which was, she felt, pushing the boundaries of what she had consented to.

This, predictably, sparked a zillion half-cooked conversations which conflated sex and sexual assault, consent and complicity and, perhaps most frustratingly, discussions about whether #metoo has gone too far.

Why did this happen? First, there was a serious problem with the way that Babe.net approached their exclusive story. It all starts to make sense when you know that ‘Grace’ did not go to them with the story she wanted to tell, instead they approached her. And, in their haste, they did not do her justice. Sadly, the language used by Babe echoed the traditional lexis of a tabloid scandal. It focused in on her wine, her outfit and on him. It did include details, but they were the wrong ones. The emphasis was on the physical – on him performing oral sex, on her performing oral sex – but there was no analysis, and while there was reference to Grace, the reporter did not properly unpack what she was feeling and thinking internally. Because of this, Babe’s reporting was a sensationalized hatchet job which left Grace’s story wide open to the inevitable criticism that followed. ‘If she didn’t like it, why didn’t she just leave’ etc. etc. Spare us.

The problem with the way Grace’s story was told is that it played into the hands of those who are critical of #metoo and warning that young women today are 'too sensitive', 'too puritanical' and 'too man-hating'. Indeed, only today did 37-year-old Conservative MP, Kemi Badoch express her belief that young people today are ‘conservative’ and ‘puritanical’ in their view of sexual harassment and appropriate sexual behaviour. Her views fall in line with those expressed by Caitlin Flanagan in a piece she wrote about ‘Grace’ and Ansari for The Atlantic in which she actually wrote the words: ‘in one essential aspect they [magazines when she was growing up in the 1970s] reminded us that we were strong in a way that so many modern girls are weak.’ Flanagan, incidentally, was born in 1961.

We should absolutely not conflate sexual harassment with sex, which is what some of the entries on the spreadsheet about sexual harassment in Westminster did when it was first released. But, equally, isn’t it time we acknowledge that there is obviously something going on which has happened because of #metoo? There is clearly a conversation about consent now happening which is not related but separate to workplace harassment, sexual assault and rape as discussed in the context of Harvey Weinstein. Why is Ansari different to Weinstein? The story of Weinstein's abuse of power is unique because of his particular privilege and power while what 'Grace' reports, on the whole, could have happened to anyone. Ansar's fame and relative power is not actually the main problem, it's a red herring.

If stories about consent or, rather, the lack of it are difficult to report could that be because we don’t quite have the right language for it? If it’s not always possible for women to recognize in the moment, could that be because we’ve absorbed so much total BS about how sex should be from (some) pornography, film and TV that we aren’t always confident in our own feelings? If men are confused about consent, might it be pertinent to ask whether their own ideas about sex have been informed by a fundamentally sexist culture?

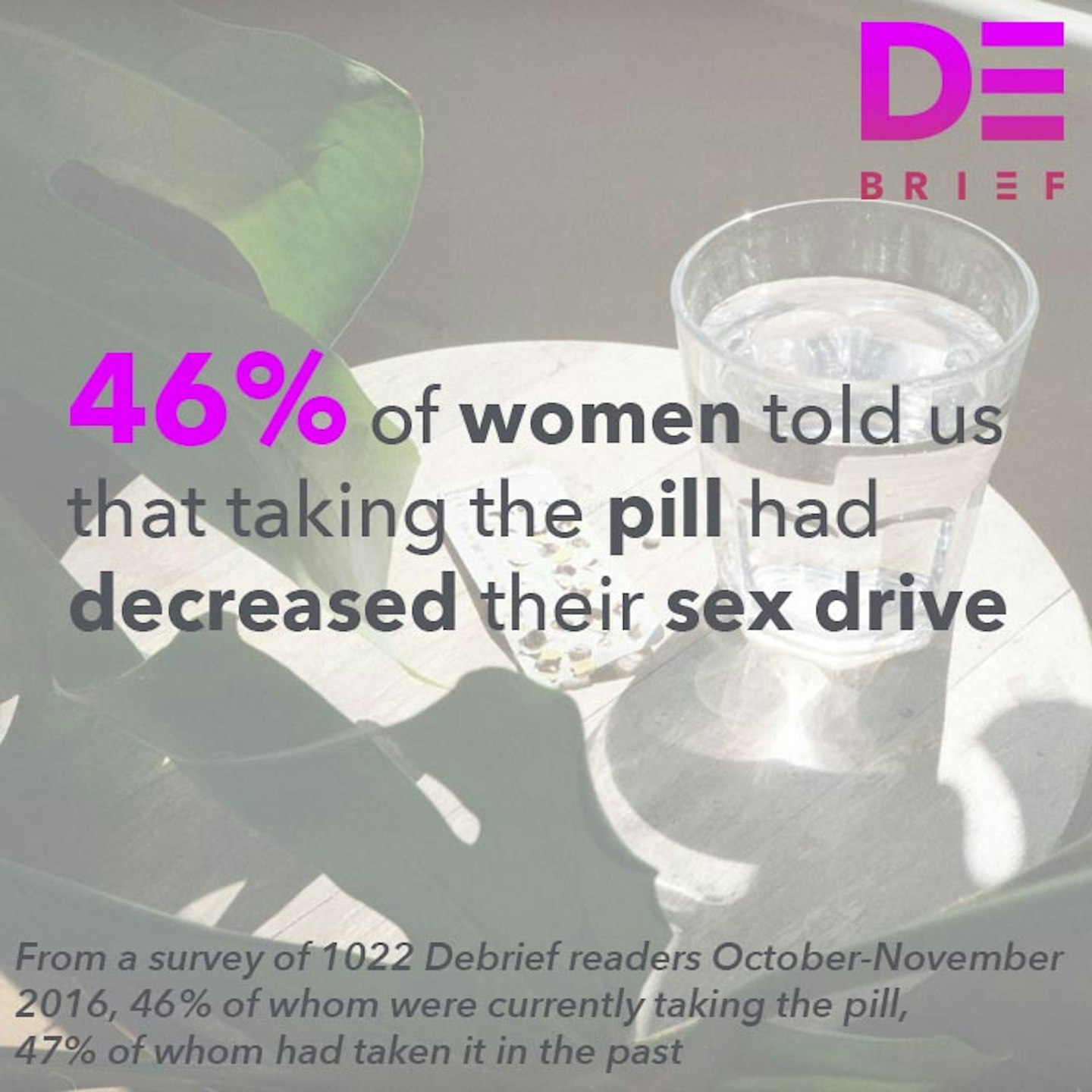

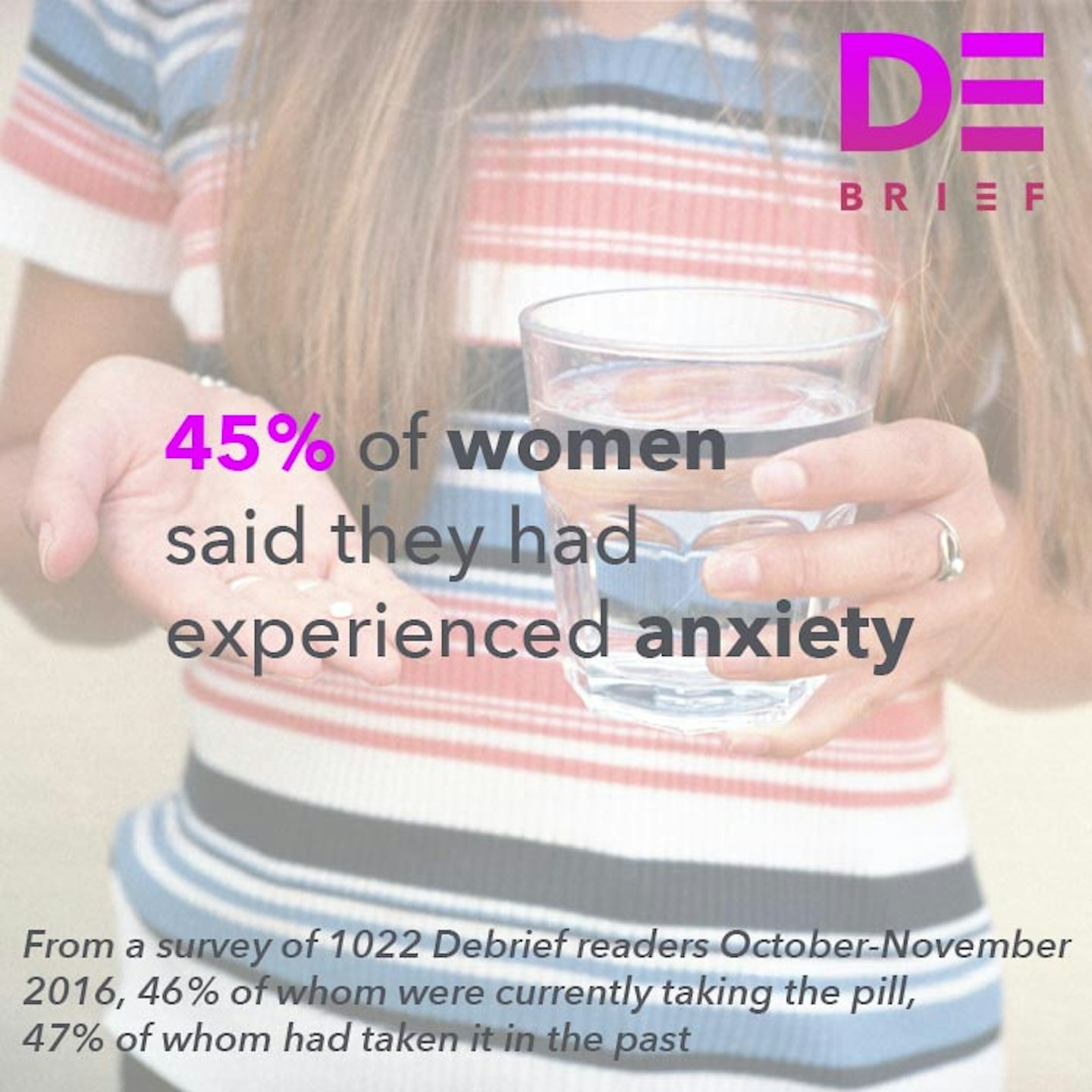

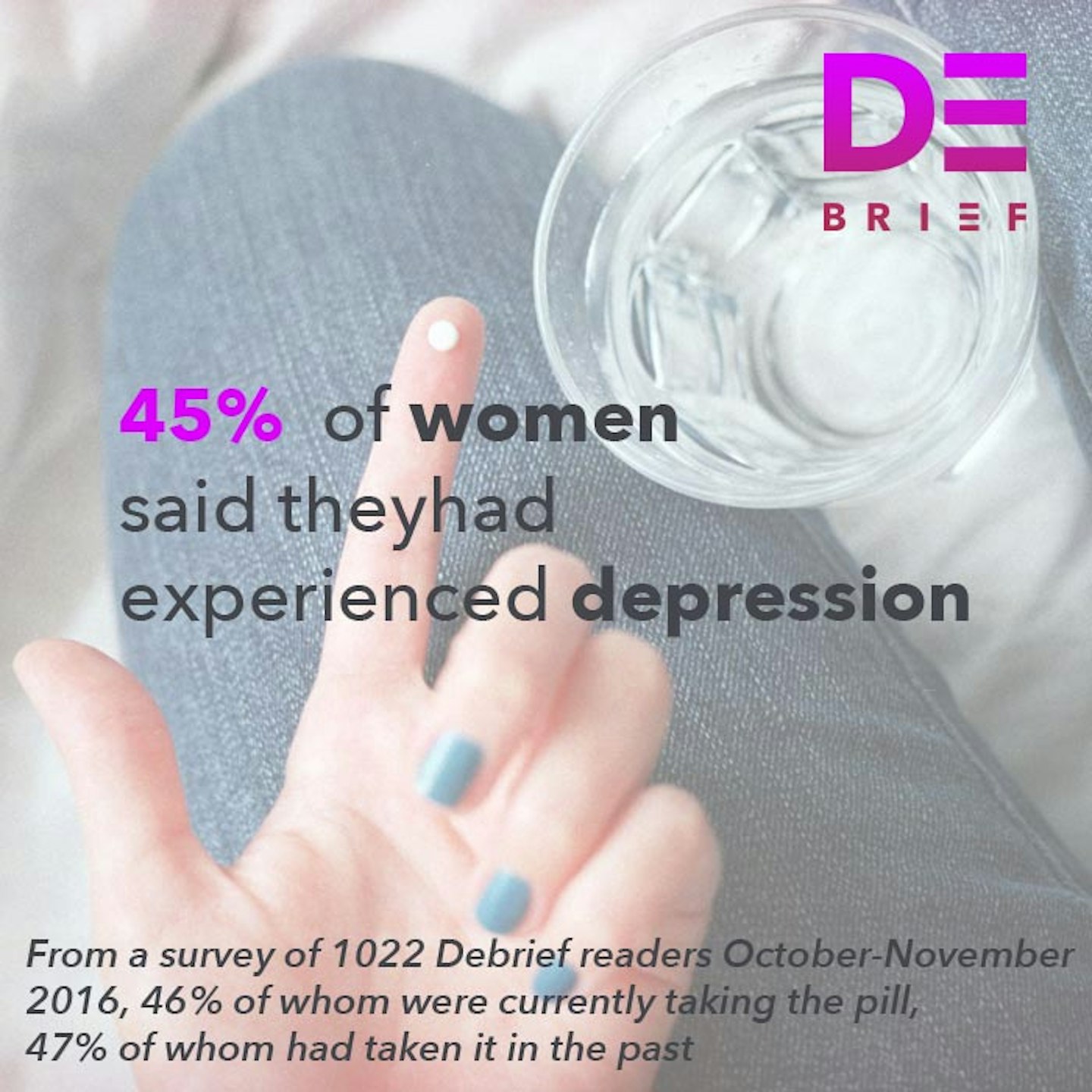

**READ MORE: The Debrief Investigates - Hormonal Contraception And Mental Health **

Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

1 of 9

1 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

2 of 9

2 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

3 of 9

3 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

4 of 9

4 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

5 of 9

5 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

6 of 9

6 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

7 of 9

7 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

8 of 9

8 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

9 of 9

9 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

Grace’s account of what happened between her and Ansari speaks to this. She recalls asking him to ‘chill’, to ‘slow down’. She says she felt he was reaching for a condom too quickly, she wasn’t ready and it unnerved her. If you’ve ever found yourself in that situation, you might have been able to get up, get dressed and GTFO of there. But, equally, you may have been trying to play the culturally acceptable role of the cool girland justifying a man’s actions to yourself. You may have been worried that if you made a fuss, if you explicitly used the word consent or asked for ‘a bit more conversation’ before sex that you would be labelled ‘frigid’, ‘up tight’ or worse. As much as we are now aware of consent, it is still the contemporary equivalent of asking someone to wear a condom. There is, whether we want to believe it or not, a certain stigma attached to it both in liberal elite circles and beyond.

I once told someone who was on top of me that I thought I was too wasted to go through with sex. I was already naked, so you might concur that up until that point I had consented. His response? He said ‘you’re going to be another notch on my bedpost anyway’. I have also been in situations where, like Ansari, men have moved too fast for me and brushed off my requests to ‘slow down’. I know, because this is what women talk about when we get together, that similar things have happened to many (if not all) of the women I hold close to me.

Those women, because I am privileged, are also privileged. They are articulate and powerful. In their daily lives, like me, they have no problem expressing themselves and achieving what they set out to achieve. But that hasn’t stopped bad sex happening, that hasn’t stopped the murky issue of consent cropping up and not being resolved in a way that made them feel good and safe and comfortable.

Does this make us ‘weak’ like ‘Grace’ as Flanagan suggests? I’ve certainly worried that I am weak, that I say one thing out loud and then, when vulnerable and confronted with a difficult situation, couldn’t connect my thoughts and my body quickly enough to measure up to myself. In the face of pressure from a prospective sexual partner, which is absolutely what ‘Grace’ is talking about, how many of us have felt ‘weak’ and wished we were strong?

What would I like to say to the ‘notch on the bedpost’ guy now? I’d love to tell him that he is abhorrent. Will I? Probably not, because I went out with him for 18 months after that incident in a warped attempt to reconcile myself with what had happened. Does that undermine that fact I now look back on that as sex without affirmative consent? No. It does, however, confirm that consent is not as straightforward as we would like it to be and emphasise the need for an open conversation about it, no matter how difficult that might be.

Like ‘Grace’, who texted Ansari after the encounter to say it had made her ‘uncomfortable’, women everywhere will know the feeling of being able to say what you needed to say once you are alone again, safe and sure of yourself. I imagine they will also know, as I do, the anger you feel not just with yourself but with the other person once you are able to order your thoughts. I spent years self-flagellating because I hadn’t been able to call a spade a spade but, then, I realized that I had been conditioned to submit to the exact sort of sex I didn’t want to have by a world which punishes women who ‘make a fuss’.

That is why the bad reporting of and backlash against ‘Grace’ are so equally damaging. Power, pressure and consent – when it comes to consent in sex there is a Venn diagram of all three things. We find ourselves caught in the centre and not always able to identify whether the right amount of each factor is present and worried about what will happen if we speak out about being unsure.

By talking about consentwe are figuring out a language for it which, in time, will mean that women like ‘Grace’ feel able to say how they’re feeling and express what they want when it comes to sex. I hope that this will also help men to understand when a woman is trying to say no or express unease.

Once again, we need to reiterate that the global movement that is currently bubbling up – whether you call it #metoo, Time’s Up or something less coherent – is not a puritanical attack on sex. Nobody is saying that sex is bad. What women, everywhere, are calling out is sexism and, in doing so, they are shining a light on how sexism has informed our ideas about how sex should be. This is why Cat Personwent viral, it was the closest thing to a distillation of how it feels to have sex when you don’t really want to as most of us have ever read.

Because, when it comes to sex, we are all unlearning our absorbed attitudes about power and control. In doing so, we are deciding what a healthy and consensual encounter looks like. I'm not ashamed to say I only know that now, at nearly 30 and I don’t feel the need to belittle women younger than me who seem surer of it than I was at their age, I commend them.

Follow Vicky on Twitter @Victoria_Spratt

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.