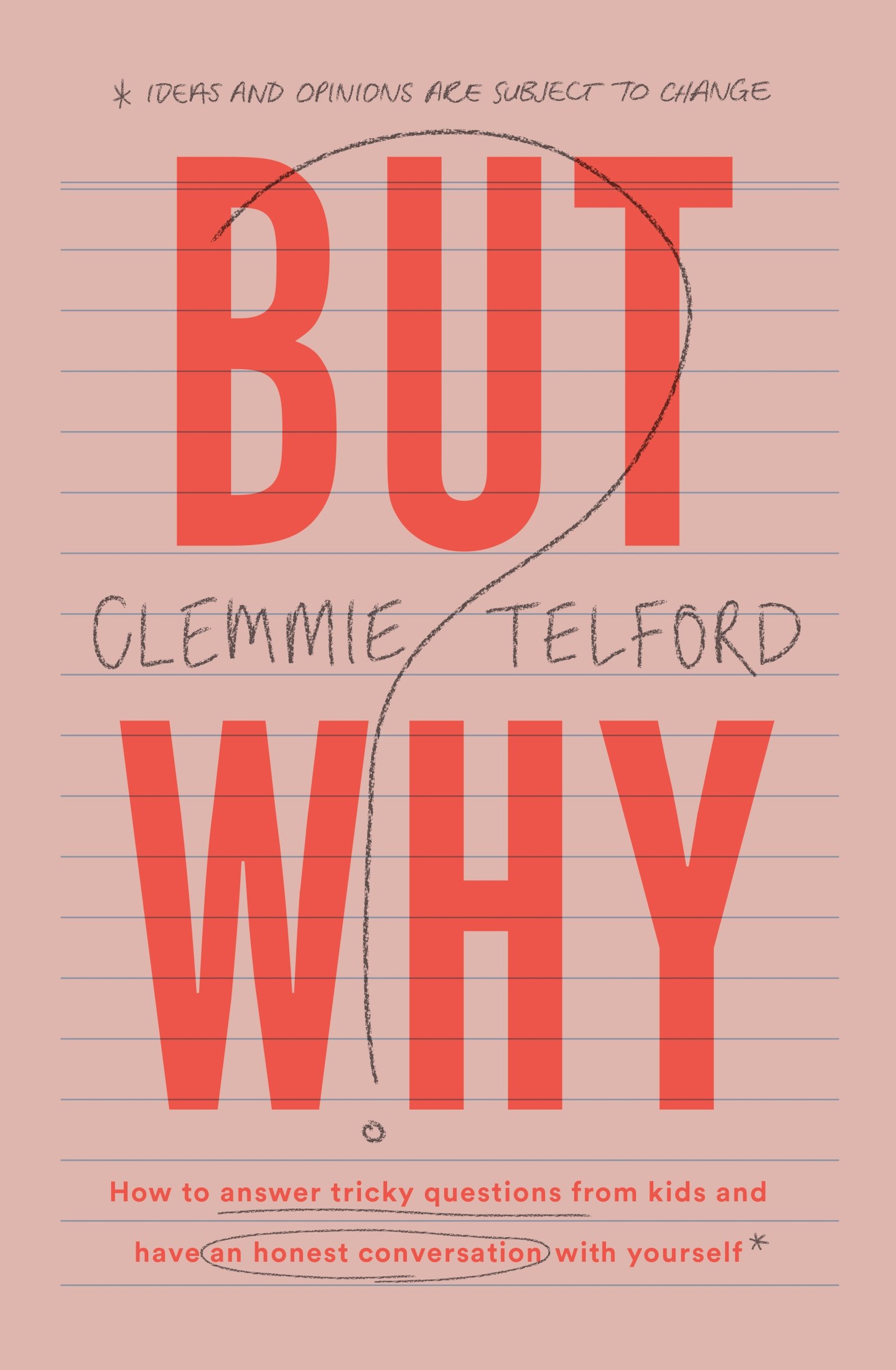

Over the last 18 months I have been up to my eyes in writing my debut book BUT WHY?: How to answer tricky questions from kids and have an honest conversation with yourself- as the title suggests my ambition was to take 34 gnarly questions and set about getting some neat conclusions.

That didn’t happen.

It seems pretty obvious but, even after months of research, there were no neat answers. Instead what I came to were some very clear learnings, in particular; rather than look for a conclusion, one of the best we can do is get comfortable with not knowing.

I would even go a step further and say not knowing is a superpower.

Let me explain...

I am a huge fan of Brene Brown – okay, that is an understatement. Hearing her speak about the notion of vulnerability being a superpower, and that embracing your weakness is courageous, was game-changing for me. ‘Vulnerability is not knowing victory or defeat; it’s understanding the necessity of both, it’s engaging. It's being all-in.’ Brene’s research on vulnerability affirmed for me that when things make me feel wobbly that is okay; in fact, it’s probably a good sign – it’s where the growth and the big stuff happens.

Her theories can also be applied to the context of answering challenging questions from your children. Sometimes this means admitting you don’t know. Perhaps that might feel shameful, or embarrassing. But not so! It’s showing that you are human.

It’s something Alain de Botton touched on when I spoke to him about ‘emotional wellness’. One thing that really stayed with me was when he said that most parents house a deep-seated fear that we are going to screw up our kids.

Yet our actual role is not to be perfect or impenetrable, it’s to introduce sooner and to plant the seed we aren’t perfect, it teaches them they’re not perfect either and that’s all the better. Being human means being fundamentally flawed and that’s so great about it. It means there is always something to learn.

I have a tendency to try to control. I like a plan; I like to research; I’m not averse to a schedule, a system or a process. That way you know where you are at, right? In many ways, yes. But we also need to allow for flexibility. In meditative practice, they talk about holding a bird in the hand – you need to find a way to keep it secure without squashing it.

It’s about having systems, but not defaults you can’t deviate from. If you aren’t prepared to be flexible then how are you going to grow?

Being certain doesn’t allow for nuance. Not knowing isn’t about ignorance. It’s about being smart enough to know when we don’t know. Confident enough to be unsure.

Better to have no opinion and be willing to explore it than to be completely rigid in an answer you’ve not taken the time to consider. As Marcus Aurelius said: ‘You always own the option of having no opinion.’

Similarly, when I spoke to Ovie Soko, professional basketball player turned author of You Are Dope, he said something that really stayed with me. When you look at a situation (in this case answering questions), be conscious of the fact that there are no right answers on your path, because you are the only one to have trodden it. You can seek wisdom from other people’s paths, but yours is yours.

What I now realise is that this parenting lark is about trying to prepare my children for unknowable experiences outside of my own. It’s also worth noting that not only is there no such thing as ‘knowing it all’, but if there was, would you actually want it?

Remember at school when you didn’t really like the ‘know it- all’ kid? Which is a bit mean, because they were probably okay really. Maybe. But a know-it-all needs a reality check.

Self-righteousness blocks conversation. Believing you are right is the opposite of the reality; nobody is always right. Because more often than not, ‘right’ doesn’t exist; there are several versions of right and several versions of wrong. And even, confusingly, several versions of ‘on the fence’. All of which are valuable.

There is great humility in saying ‘I don’t know’. Be brave enough to sit with not having a clue. Be gracious enough to admit, ‘I didn’t know that, thanks for telling me.’ Be humble enough to say, ‘I don’t know yet, but I am figuring it out.’

In Zen Buddhism they talk about shoshin, a word meaning ‘beginner’s mind’. It refers to having an attitude of openness, eagerness, and lack of preconceptions when studying a subject, even when studying at an advanced level, just as a beginner would. When I was a kid, I had this idea that as soon as I got to a certain age I would have figured it all out: when I’m a teenager I’ll ‘get it’, when I get to university I will figure it out, or when I become a mum I’ll have things nailed.

Now I understand that I’ll still be saying that when I am a granny. There’s always stuff to learn. There are always unanswered questions. The world is changing. You are changing. Every time you think you’ve worked it all out, it’ll change again (very much like parenting).

Next time one of my three kids lands me a really tricky, sticky question, I am going to take pleasure and pride in saying, ‘I don’t know. But let me come back to you…’