The other day, I overheard my five-year-old’s history teacher pronounce his name incorrectly in a live lesson. His name, of Persian origin, is not at all hard to say, so after asking my son, I waved at her through the computer screen to get her attention and politely corrected her. It was, in a way, no big deal, but in another way it sort of was.

For most of my life, people have mispronounced my name despite my attempts to constantly correct them. As a teenager, it made me resent the Persian name my Pakistani parents gave me and then it made me resent everything about being Pakistani too. I don’t ever want my children to feel that way. I want them to be proud of their names, and what they stand for, so it matters to me, that I was able to do this one little thing for my son.

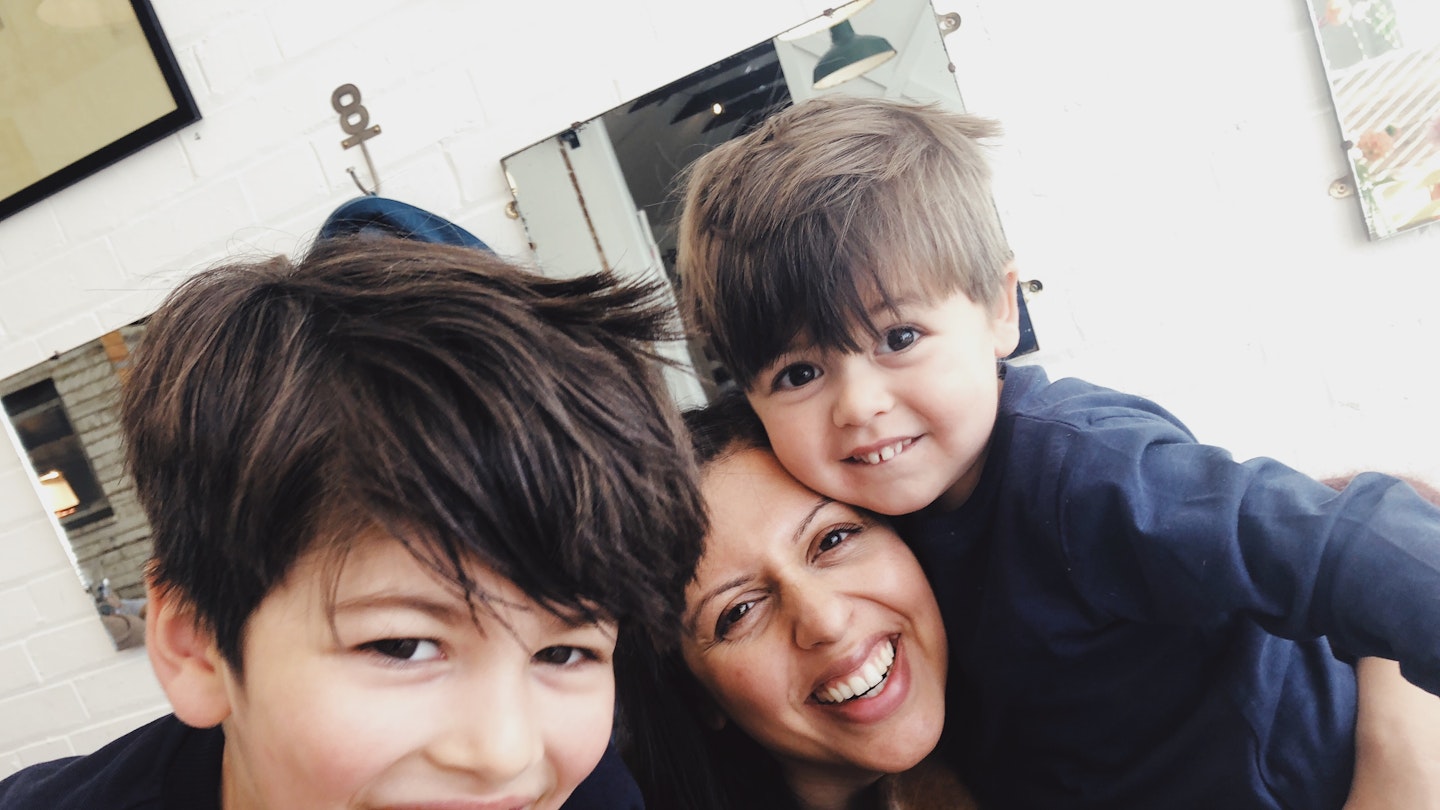

My husband is white and my three children easily pass as white, and so in a way, their names are all they have to notably, visibly, connect them to my heritage (many Pakistanis have Arabic or Persian names), though we did admittedly cave and anglicise the spelling of our youngest child after, third time around, it was getting tedious to correct everyone. My children sometimes find it funny that out of all of us, my husband, Richard, has the most “ordinary” name out of all of us.

It is more than just giving them certain names, more than just knowing what Ramadan is. It’s a feeling that sometimes I find hard to put into words.

Before Richard and I married, he converted to Islam. My Pakistani, Muslim family had a lot of questions, when I first told them about him. One of those questions was: how would we raise our kids to know that they were Muslim, to know their Pakistani side and where they came from? Race and religion are two separate entities but they are also closely entwined. I was reminded I’d need to make a real effort to teach my children about their Pakistani origins and their religion, because their sense of identity would not be a given. Because otherwise my half-Pakistani, Muslim children might risk feeling lost.

Sometimes when I look at my children, I hear those same questions in my head: how will I raise you to know that you are Muslim, to know your Pakistani side?

My efforts feel far too basic because honestly, I don’t know how to do it. I try to encourage them to eat Pakistani food, even though all they really eat is the naan. I tell them about the meaning of their names. As babies, I taught them to count to ten in Urdu, to say salaams to my side of the family. It feels important to prove I am making an effort, only to whom, I do not know. But sometimes I worry it is not enough. And other times, I’m frustrated, because I don’t want to teach my children about their background as though it is a subject, a checklist. Because it is more than just giving them certain names, more than just knowing what Ramadan is. It’s a feeling that sometimes I find hard to put into words.

Available in hardback and paperback

These days, I’ve eased off trying to “teach” them about where they come from and have decided to simply show them, let them absorb it for themselves. I try to surround them with what I love most from my Pakistani upbringing: family and the sense of warmth surrounding kitchen tables spilling with an overabundance of food. It’s exactly what I think of when I think of my husband’s English family too. I think of the values of faith I hold most dear; honesty, love, kindness, generosity. These are the sort of values I’d want to pass onto my children, regardless of religion or background. None of this is exclusive to one sort of identity over another.

I try to remind myself that this is how they will learn who they are: from seeing it, living it, breathing it. And I hope that it is in this way that they will be proud of both sides of who they are too.