I had suspicions early on that becoming a mother might be difficult for me. But I couldn’t have anticipated the years of struggling to conceive, pregnancy losses, surgeries and doing everything I could to improve my chances - meditation, yoga, fertility diets, acupuncture, naturopathy and more - before my husband and I decided to try IVF.

When, at last, I held my daughter in my arms, all I felt was joy. Within weeks, however, a fear had crept in. I had grown her, birthed her, but I didn’t feel certain that we shared DNA. If not, I didn’t even want to think about what that would mean, or what I would owe to the woman whose child I was raising.

Where did these fears come from? Those first weeks as a new mum are a blur. All of my focus was on keeping my daughter alive, safe and fed. We were in and out of hospital and the doctor’s office as my milk failed to come in, and then failed to come in enough. I breastfed 15 or more hours a day. I slept in 45-minute spurts… if at all.

As the weeks went on, things got easier. We left the house. People cooed about how beautiful my daughter was, how elated we must be (we were!), and how she was absolutely, unnervingly, the spitting image of my husband.

I started to see it, too. Like me, she had dimples. But in no other way could I see myself - a mixed-race Black woman - in my child. Not in her skin, which was paler than my white husband’s. Not in her hair, which was blonde and straight. And not in her grey eyes - a colour that, as far as we knew, didn’t exist on either side of our family trees.

'My husband asked if we should get her DNA tested. Terrified that some woman may be out there, wanting to stake a claim on my child, my answer was no'

Lots of people have dimples, so they weren’t enough to contend with my growing fear. It didn’t help that, when out with white friends, strangers assumed my daughter was theirs. Or that a kindly-seeming elderly man commented how fun it must be to have the job of taking care of such a beautiful child. He may have meant the ‘job’ of motherhood, but it’s unlikely. Once, my husband even asked if we should get her DNA tested. Terrified that some woman may be out there, wanting to stake a claim on my child, my answer was a firm no.

Thankfully, by the time my daughter was one, her hair curled, her eyes turned brown, her features shifted and I became certain that she was biologically mine. This confidence gave me the freedom to explore, through fiction, all the possibilities I hadn’t wanted to consider.

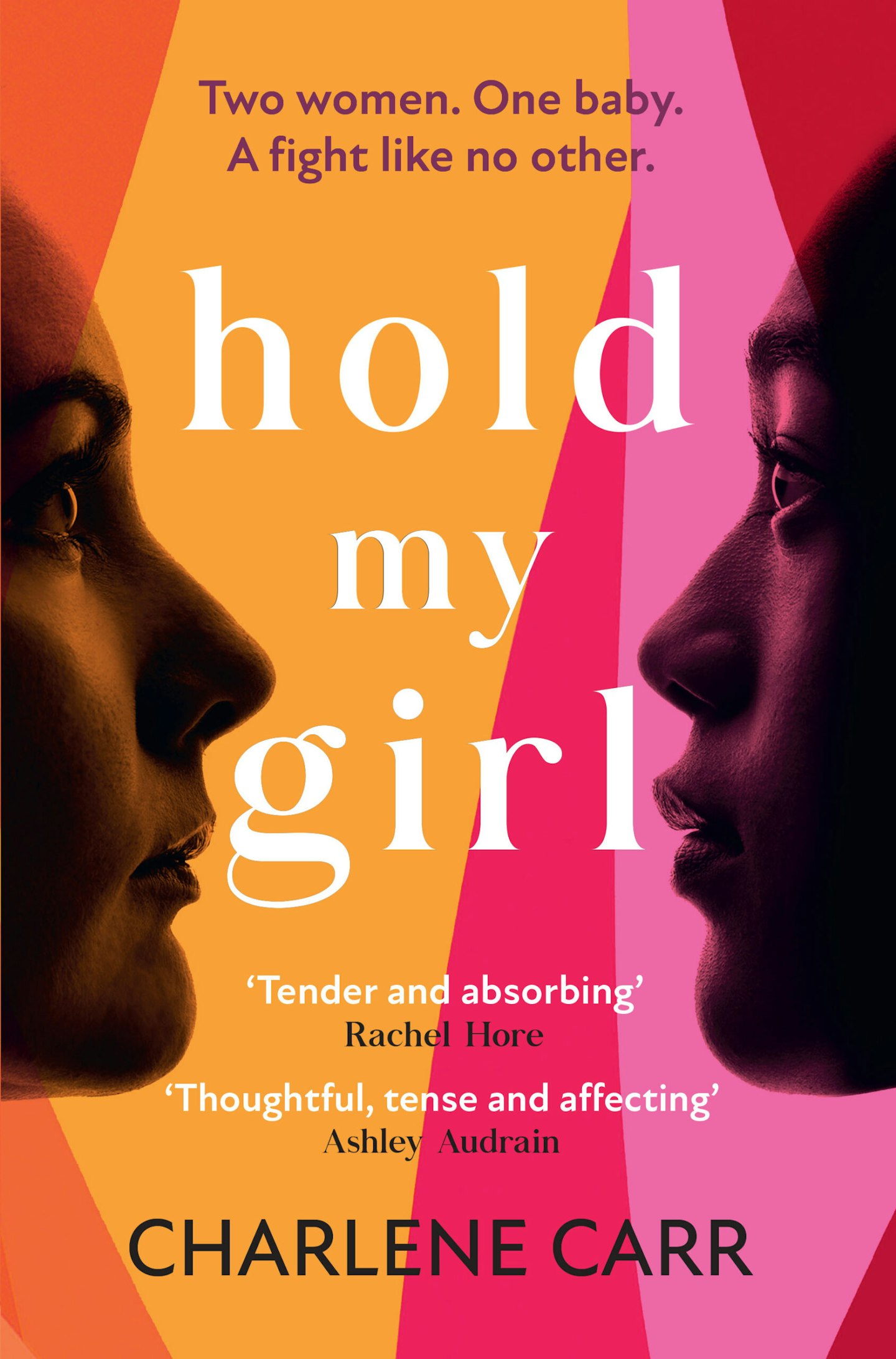

As I sat down to write my novel, Hold My Girl, about an egg switch at a fertility clinic, the question of which mother deserved to have this child remained unanswerable. In trying to solve that for the reader, the novel quickly turned into an examination of not just my initial questions, but of what makes a mother, and how biology is only one possible aspect of it.

Remembering the strangers who found it hard to see my child as mine, race, I knew, would have to play a role in Hold My Girl. And so it became something the birth mother, whose baby emerged a visibly different race, had to grapple with. Even now, with full confidence that my daughter and I share DNA, there is still anxiety – in the assumptions strangers make that she isn’t mine, in how people will label her and how I’m supposed to help her navigate that as a visibly white child who will encounter challenges in defining herself and determining her identity. Who, at the age of five, already has.

Another aspect I explored is the pain of infertility and of pregnancy loss. While I was writing the novel, we tried for a second child. I went through multiple rounds of fertility treatment and embryo transfers and had multiple pregnancy losses. Each time, I put the manuscript aside to grieve. But each time I came back with more heartache and also more strength, as a mother not only to the child I was able to hold in my arms, but to yet another one I never would.

Hold My Girl delves into these intimate pains with the goal of helping to normalise the unique struggles many couples face in their efforts to build a family. It is an exploration of infertility, IVF, racial identity, the often-unseen trauma of pregnancy loss, and motherhood in several of its many forms.

To anyone who is going through or has gone through this journey: I hope, as you turn the pages, you’ll feel a little less alone and a little more seen.