Why aren’t women having babies? It is, with birth rates falling below replacement rate, a question which is worrying the education secretary Bridget Phillipson – as well as politicians, economists and policy experts around the Western world. But perhaps they should just ask the pop star Chappell Roan.

‘All my friends who have kids are in hell,’ the 27-year-old said on Call Her Daddy recently. She added: ‘I actually don’t know anyone who’s happy and has children at this age. I literally have not met anyone who has light in their eyes, anyone who has slept.’

Her blunt delivery drew criticism – but I think those who accused Roan of undermining mothers were missing the point. There are now only 1.44 children per woman in the UK, the lowest on record, and down from nearly three in the 1960s. Roan is of the age when, traditionally, most women would have been thinking seriously about motherhood, and she – in common with many others of her generation – is unenthusiastic. Because right now, motherhood is getting a seriously bad press.

It's become less taboo in recent years to talk openly about the more challenging aspects of motherhood. We’re more open about the physical, emotional and psychological toll of pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding. But has all this ‘openness’ gone too far – and are we at risk of creating an unnecessarily downbeat view of parenthood?

Openness about the negative side of parenting has come with the trend for more openness generally – especially about our mental health. But I also suspect that motherhood does genuinely feel like a less positive experience for modern mothers, for a number of reasons – and not all of those are to do with the profound financial and logistical challenges around flexible working and affordable childcare (which Bridget Phillipson would do well to note.) There are more subtle factors at play here, too.

For women of the 1950s and 60s, motherhood – stifling and unsatisfying as it may have felt to many women - was what women were supposed to long for. It was a feminine ideal; something with kudos, that was revered and celebrated. Prior to their marriage, few women had any sort of professional status or had tasted financial freedom; women weren’t even allowed mortgages or hire purchase agreements.

By contrast, in the late-capitalist society of 2025, the unpaid work of caring for children is generally regarded as a low-status endeavour. Women are active, even dominant, in many areas of the workplace, and tend to delay motherhood beyond their twenties; in the meantime, they become accustomed to high levels of professional status, financial independence, ample social, health and leisure time. As a result, when they experience motherhood, it feels like a ‘status downgrade’ in a way that previous generations of women would struggle to relate to.

For those used to being respected and valued in the workplace for their skills, experience and intellect, the handbrake turn to being at home pureeing carrot and then wiping it off the floor three times a day can feel mortifying. ‘Compared to what I used to do … it's a really hard transition, and it's not fun,’ said former British number one Johanna Konta, who admitted she found being a mother ‘monotonous’ and ‘boring’ in comparison to her former ‘selfish existence’.

Reality star and political commentator Ashley James, of Channel 4’s Made in Chelsea, admitted she had ‘found a lot of the baby and parenting stuff quite boring’ with her son Alfie – so much so that at times, she ‘thought she’d ruined her life’. She added: ‘I'd dread being on my own with him for long periods… I'd find myself just wishing I had my old life back.’ Actress Keira Knightley has also described adjusting to parenting as ‘really f— difficult’.

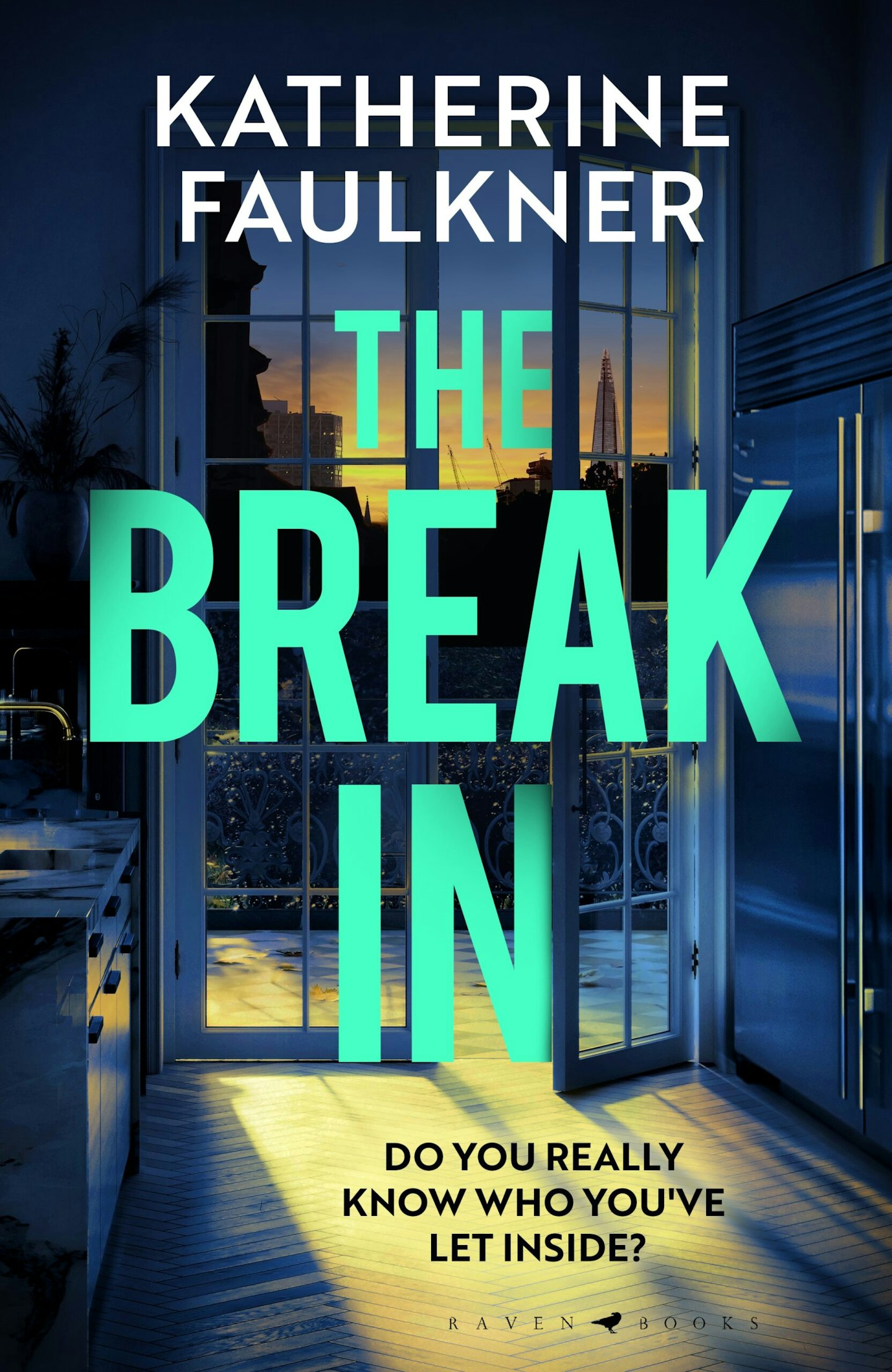

This psychological struggle – and the accompanying guilt at not ‘loving motherhood’ in the way you’d expected - was something I found fascinating, and it became a major theme in my psychological thrillers. Often dubbed ‘mum noir’, my novels explore this darker and more psychologically challenging side of motherhood – the psychological strangeness of pregnancy, the way in which motherhood can distort female friendships, the emotional and financial strain of working parenthood. In my latest novel, The Break In, the vulnerability - as well as the unexpected, disorientating strength of maternal love – is explored in the context of an unfolding parental nightmare for protagonist Alice, who is hosting a play date for her young daughter when an intruder breaks into her home.

Judging by the spate of novels dealing with similar themes that have emerged in recent years – including The Push and Soldier, Sailor – I’m not the only one who was dying to have these sorts of conversations about the darker side of motherhood. But though I found motherhood difficult, and psychologically strange, I’m also very glad I did it, and I really do love being a mother to my three children. I feel uneasy about the idea that I’ve been part of a wave of negativity that has put younger women off the idea altogether.

The problem is that like so much else in the age of social media, discussions of motherhood have become polarised. Few of us hold extreme positions on our own choices or anyone else’s. Hardly anyone thinks that enjoying being at home with your children means you’re some regressive ‘tradwife’, or – by contrast – that being child-free by choice means you’re heartless or selfish. Yet the tenor of the discourse can make women feel pitted against each other.

In such an atmosphere, just talking about the good parts of motherhood can start to feel somehow controversial – akin to ‘choosing a side’ in a toxic debate. Most of us also know women for whom fertility has not been a straightforward journey, so expounding publicly on the joyfulness of having children can feel smug and insensitive. It feels easier to stay silent.

But perhaps by shying away from talking about the good things about parenthood, we’re at risk of holding up a distorted picture for the next generation of women. On her podcast Straight Up, the journalist Eleanor Halls said recently: ‘As someone who is still on the fence about having children, I feel like I’m overwhelmed by negative stories. I have got to a place now where I am craving not idealised, glossed-over versions of motherhood and birth, but just nice ones – nice, positive stories that don’t dwell on all the tears and the marriage breakdowns and the regret.’

The truth is that it’s complicated. Motherhood was not what I thought it would be – it’s been both worse and better; harder and more complicated (and more expensive) than I’d ever imagined. But the upsides, too, have been unexpected.

When I held my first child, it was a thunderclap - like falling in love, but different: harder, fiercer, more physical, more powerful and more frightening. A love that makes you vulnerable, but also strong. And yes, lots of things I valued before – including but not limited to hot baths, my career, yoga, and pedicures– were pushed far down my internal pecking order underneath her constant, clamouring needs.

But so were things which probably deserved the downgrade – like worrying about my roots, or the way I looked in a swimsuit. Caring about what other people thought generally, in fact. I’d spent my twenties worrying about what other people might think of me if I wrote a book and then it never got published and I was left looking foolish. Looking at my sleeping daughter one day, I realised one day that I only really cared what she thought of me, now. Much better, I realised, to be able to tell her one day that I’d at least given this thing- which had always been my dream - a shot. And, because of her, I did.