This is your weekly instalment of WTF is going on because, these days, a lot can happen in a week…

There is a sentence from Kristen Roupenian’s short storyCat Personwhich I have re-read multiple times since it was published in the New Yorker:

‘She tried to bludgeon her resistance into submission by taking a sip of the whiskey, but when he fell on top of her with those huge, sloppy kisses, his hand moving mechanically across her breasts and down to her crotch, as if he were making some perverse sign of the cross, she began to have trouble breathing and to feel that she really might not be able to go through with it after all.’

Have you ever tried to ‘bludgeon’ your ‘resistance’ to a sexual encounter into ‘submission’ because you wanted it to work or felt it should? Have you ever succeeded in this act of self-suppression, only to find that, perhaps, your body knows you better than you know yourself?

I have.

It’s something I’ve wondered about a lot in recent years and particularly since the #MeToo conversation began, mostly at night as I drift off to sleep. Why have I had so much bad sex that I wish I hadn’t had? Had I fully consented to that sex? On some occasions I definitely had but, on others, the line is more blurred and not just because of beer goggles.

Why does this happen? Some people, like *New York Magazine’s *Andrew Sullivan argue that would argue that it doesn’t really happen and that this is ‘just how sex is’ by coopting a pseudo-scientific argument about masculinity, maleness and ‘nature’ which he, at no point in his writing, is properly able to define.

In an acerbic critique of contemporary feminism ‘men, especially young men’ Sullivan writes, ‘will begin to ask questions about why they are now routinely seen as a “problem,” and why their sex lives are now fair game for any journalist. And because our dialogue is now so constrained, and the fact of natural sexual differences so actively suppressed by the academy and the mainstream media, they will find the truths about nature in other contexts’.

It’s an interesting argument. Are the current conversations about consent and bad sex really stemming from a collusion between the establishment and mainstream media to suppress ‘the truths about nature’? I wonder.

Thinking back to the sex education I had at school, it certainly seems to ring true although perhaps not in the way Sullivan has in mind. Nothing was taught about what good sex should feel like, orgasms didn’t come up one and I would be willing to put money on no teacher ever once uttering the word ‘clitoris’.

The perfunctory practicality of intercourse was addressed. The emphasis was on one thing and one thing alone – male ejaculation. This, we were taught, is the aim and end point of all sex. This is what you should expect. This is what you should guard against. You don’t have a penis but we’re going to teach you all about them and never once discuss the body parts that you have which also play a part in sex, except, of course, your vagina which is where you will receive the penis. You should fear this penis because it might impregnate you and then you will end up like this 17-year-old young woman at the front of the class telling you how much giving birth to her baby hurt.

That was the extent of the sex education I received, not at a private or religious school but at a bog-standard state comprehensive. I learned that I had the ability to orgasm when it happened for the first time in my early twenties. My boyfriend at the time was shocked because as much as ‘clitoris’ doesn’t feature on the curriculum female ejaculation is nowhere to be seen, and immediately said ‘don’t do that again’.

Is it possible that what Cat Person and the young woman who told her story about a sexual encounter with Aziz Ansari have touched on is this? Unlike #MeToo they are not clear stories about an abuse of power which culminates in a sexual assault. They are, rather, tales which investigate what happens when we only teach people (both men and women) about phallogocentric sex and male pleasure. In 2017 a BBC survey found that nearly 1 in 10 British women found sex painful and, in 2015, a different study found that 66% of 18-24-year-olds were too embarrassed to go to their doctor to talk about their vagina or any related health issues.

What these studies tell us is that young women feel shame about their own bodies and, often, suffer in silence. Where does the stigma come from? To paraphrase Simone de Beauvoir, you’re not born being ashamed of your vagina but, rather, learn to be embarrassed by it because of pervasive sexist stigma. Sullivan says that #MeToo is about ideology and not reality but surely the reality is that our sex lives have long been dictated by a pervasive and (largely) male-centric ideology.

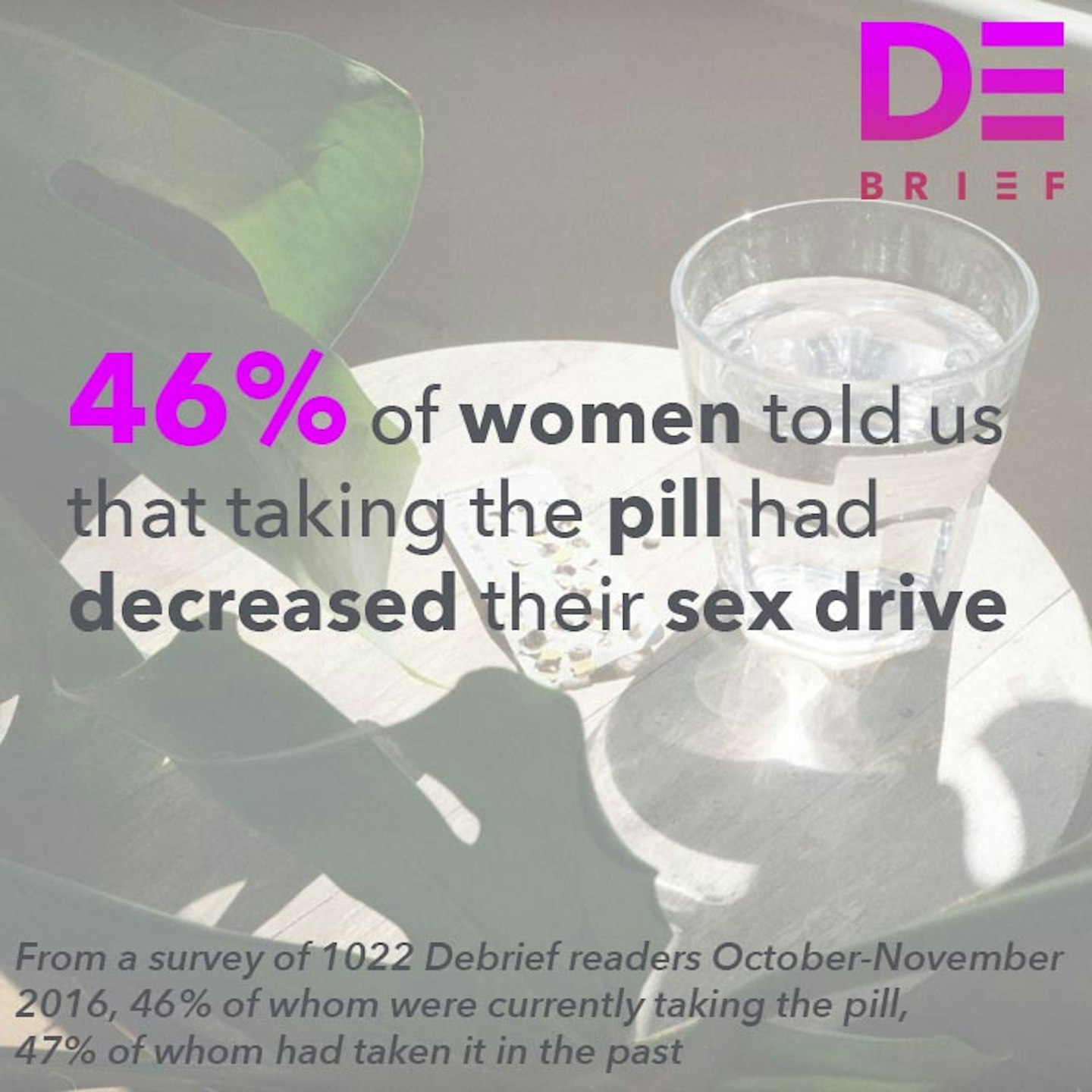

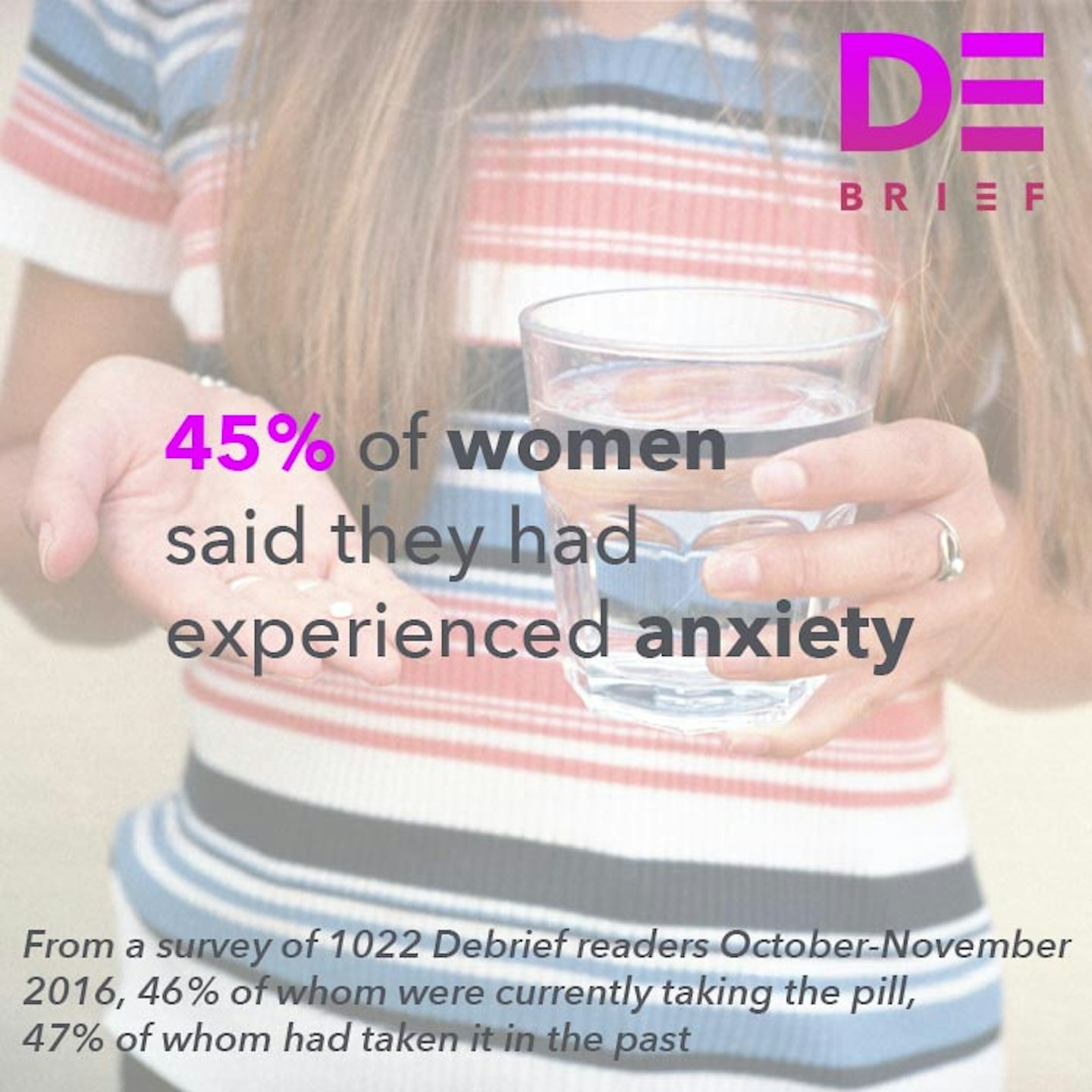

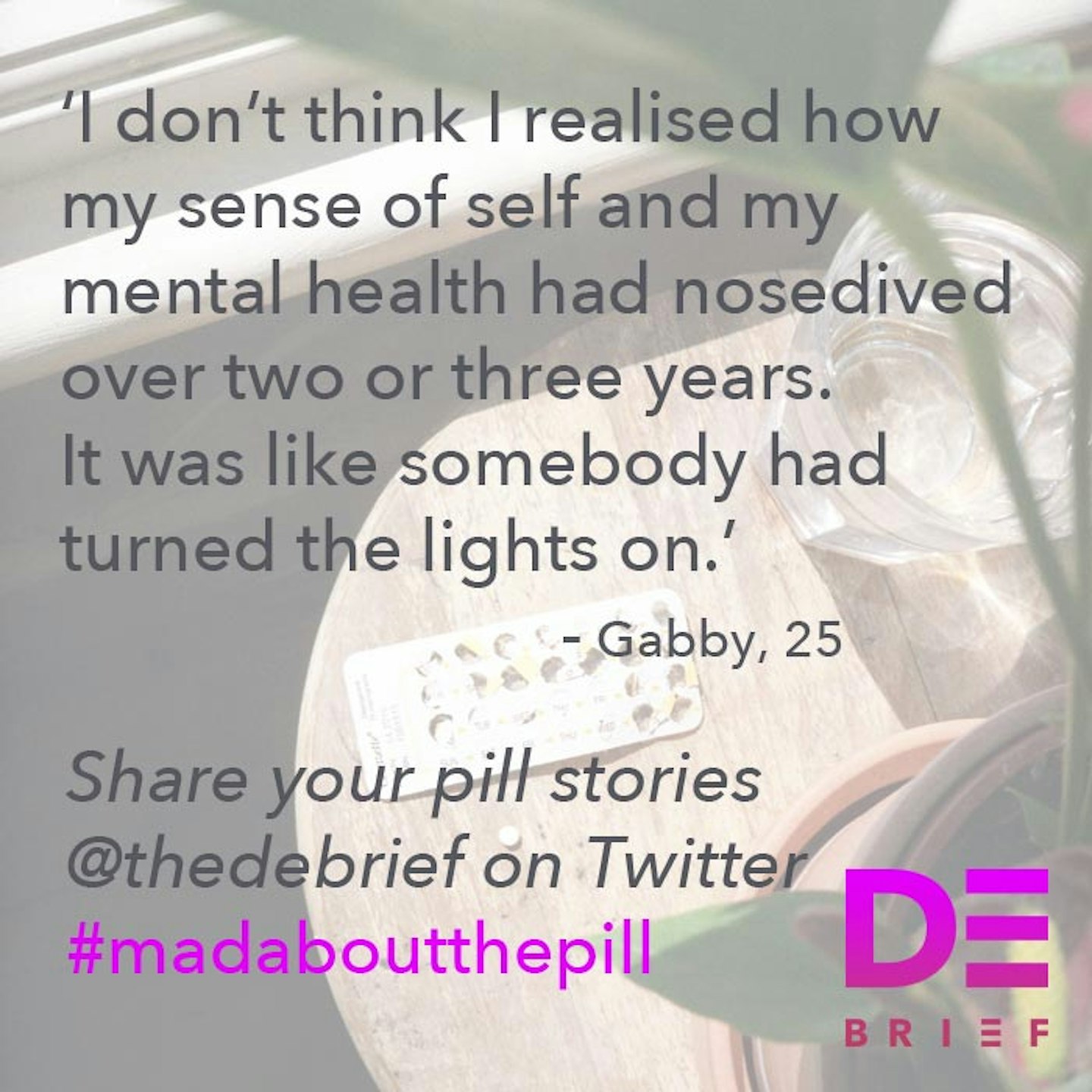

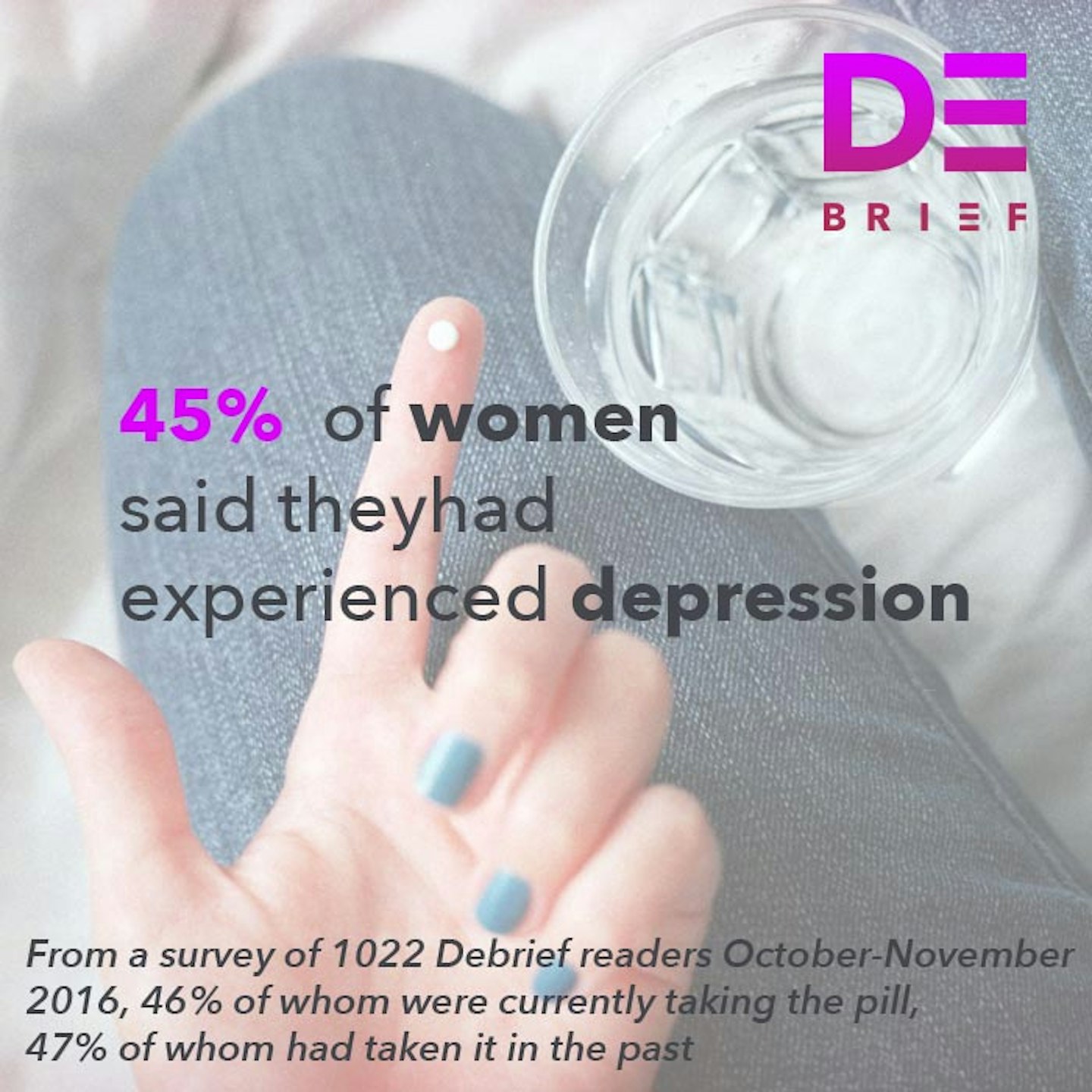

**READ MORE: The Debrief Investigates - Hormonal Contraception And Mental Health **

Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

1 of 9

1 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

2 of 9

2 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

3 of 9

3 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

4 of 9

4 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

5 of 9

5 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

6 of 9

6 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

7 of 9

7 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

8 of 9

8 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

9 of 9

9 of 9Debrief Mad About The Pill Stats

The subject of sexual consent and relatedly what constitutes good and bad sex ought to be simple. And yet, we have made it seem very complex. Good sex is not the problem here. Nor is everyone’s moral panic: ‘over-sexualisation’ and pornography. The problem is sexism and a universal reluctance to talk about women’s bodies, women’s pleasure and women’s health.

Surely the fact that young women are taught more about how not to get pregnant than they are about orgasms or gynecological health in sex education classes must be down to inherent structural sexism? Understanding pleasure is key to understanding good sex which, in turn, is crucial for understanding consent.

But, if young women don’t feel comfortable talking about their genitals in the context of their health how can we expect them to talk about them in relation to consent and pleasure. Campaigns such as Ladies Come Firsthave been advocating a sort of sex education which focuses on pleasure for some time. They believe that sex education is too negative, only focusing on STIs and unwanted pregnancy.

Indeed, a report about consent published by the Children’s Commissioner for Englandback in 2013 touched on this. ‘Gendered codes of behaviour and victim blame’ it said, ‘change how [young people] make sense of sexual negotiation’ despite the fact that they understand what consent means perfectly well in an abstract sense.

The problem, according to this report, is that sexual encounters and the consent which is supposed to come before them take place within a broad context of inequality between the sexes. One of the only publications to pick up on this part of the report was the New Statesman:

‘For many [young people], young women are held responsible for ‘getting themselves in situations’ and expected to physically or verbally demonstrate refusal, while young men are presumed to be reckless about whether or not young women want to have sex, along with a spectrum that ranges from failing to seek consent, through manipulation and persuasion to pressure and coercion.’

This was written almost five years ago but it could have been published yesterday. We know what consent is but we don’t necessarily connect it with good sex. By this I mean sex that is not just geared towards a male orgasm or power trip, sex that focuses on a woman’s pleasure as a precursor to comfortable and enjoyable intercourse for all as opposed to as an afterthought.

Classic virginity-loss scenes from TV and cinema are the sex education that goes on beyond the classroom. For my generation, it was Cruel Intentions. From it we learned that sex when you’re young and reasonably inexperienced should be difficult and painful. The male partner might ask if you’re OK and you’ll pretend that you are and then it will be over. In your head, you’ll be willing it to end but you think it’s what you’re supposed to want so you never let on for fear of being embarrassed in front of your male partner.

It’s time we stopped looking at consent as in isolation in sex education and reframed it in relation to good, pleasurable sex as a public health issue. We need to teach girls to listen to their bodies and young men how to interact with them. If you’re not enjoying sex then you’re well within your rights to withdraw consent and ask for it to stop.

Follow Vicky on Twitter @Victoria_Spratt

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.