Where were you when the 9/11 terror attacks on the US happened? We all remember, it was the first major terror attack on Western soil that a generation of people who didn’t grow up with the IRA in the background were exposed to. The so-called ‘war on terror’ which has been raging since, kickstarted our adolescence.

When I have trouble understanding, comprehending or getting my head around something, as with the awful events in Brussels this week, I usually turn to things I have previously read which have stayed with me. ‘Anything can happen to anyone, but it usually doesn’t. Except when it does,’ American novelist Philip Roth wrote in The Plot Against America (2004). The novel, written and published just after the terror attacks of September 11th 2001, is an alternative history or anti history which transports Second World War events from Europe to East Coast America. It plays on the ‘what ifs’ of history, constantly asking ‘what if so and so had become prime minister instead?’, ‘What if Hitler had lived?’… ‘What if she hadn’t boarded that plane?’, ‘What if they’d boarded a different train?’

It’s the sliding doors school of history which also applies to the way atrocities are reported on. Asking ‘what if it happened here?’ explores society’s collective anxieties, reminding us of the lack of control we have over the global geopolitical narratives that, inevitably, shape our lives. History has the power to blindside us. It can creep up alongside us when we least expect it and change the course of things. It is, in the truest sense, always behind us.

Since 2001 we have, regrettably, been exposed to many more atrocities than any of us would have wished for. The extreme, the horrific and the unfathomable fills headlines and gets hashtags but how do we relate to this information? How do we decode and digest what we know is happening far away in Syria or see closer to home in Brussels or Paris? What sort of affect does it have on our society and psyche?

A Ripple Effect Of Disbelief

This week, in the aftermath of atrocious attacks which killed over 30 people and injured around 200 in Brussels, thousands gathered in the city to create an improvised memorial, using chalk to write messages of respect, support and defiance.

Across Europe, landmarks like Berlin’s Brandenburg Gate and the Eiffel Tower in Paris were lit up with the Belgian flag’s colours, as a show of solidarity and mark of respect for the victims of the attacks. Downing Street’s flag flew at half mast.

Online, public expressions of grief and sympathy swelled on social media. Some took to social media, sharing cartoons of Tintin meant to show solidarity and, as with #JeSuisParis and #JeSuisCharlie, #JeSuisBruxelles was trending for most of the day on Twitter. As did feelings of fear, anxiety and anger. The hashtag #StopIslam was also trending. Many people pointed out that the UK’s reaction to an attack in Brussels, as with Paris, was disproportionate compared to recent, multiple attacks in Ankara which left 46 dead.

Why do some atrocities resonate more than others? Professor Chris Brewin is a professor of psychology at UCLwho has studied mental health following terrorist attacks, both of the general population and direct victims. ‘The Francophone community may be feeling particularly sensitive right now’ he says, ‘hearing people talk about what happened in your own language makes it much easier to relate to the incidents.’

As to whether or not we numb ourselves to the magnitude of terror, the threat of it and the saddening, appalling and gruesome consequences of it he says ‘people do have to have protective mechanisms otherwise one would feel under threat the whole time – of course if you have a psychological disorder like PTSD you do feel under threat the whole time’ However ‘most people are able to supress those thoughts and memories…there are limits as to how much feeling intensely other people’s distress is possible.’

Collective Grief and Social Media Solidarity

After the attacks in Paris last year it was online grieving, something intended to bring people together, to unite them, that ended up dividing people.

It wasn’t only monuments whose colours were changed to that of the Tricolor flag, people’s Facebook profile pictures also took on red white and blue hues. Many people responded by clicking on the option to do this to their own profile. Accusations of ‘clicktivism’ were levied at people who did this, dismissing this as a tokenistic response to tragedy and the politics of who did and who didn’t adopt the profile picture colours, how long you were supposed to leave it for and whether it was now meant to happen whenever something bad happened anywhere in the world were complex and much discussed.

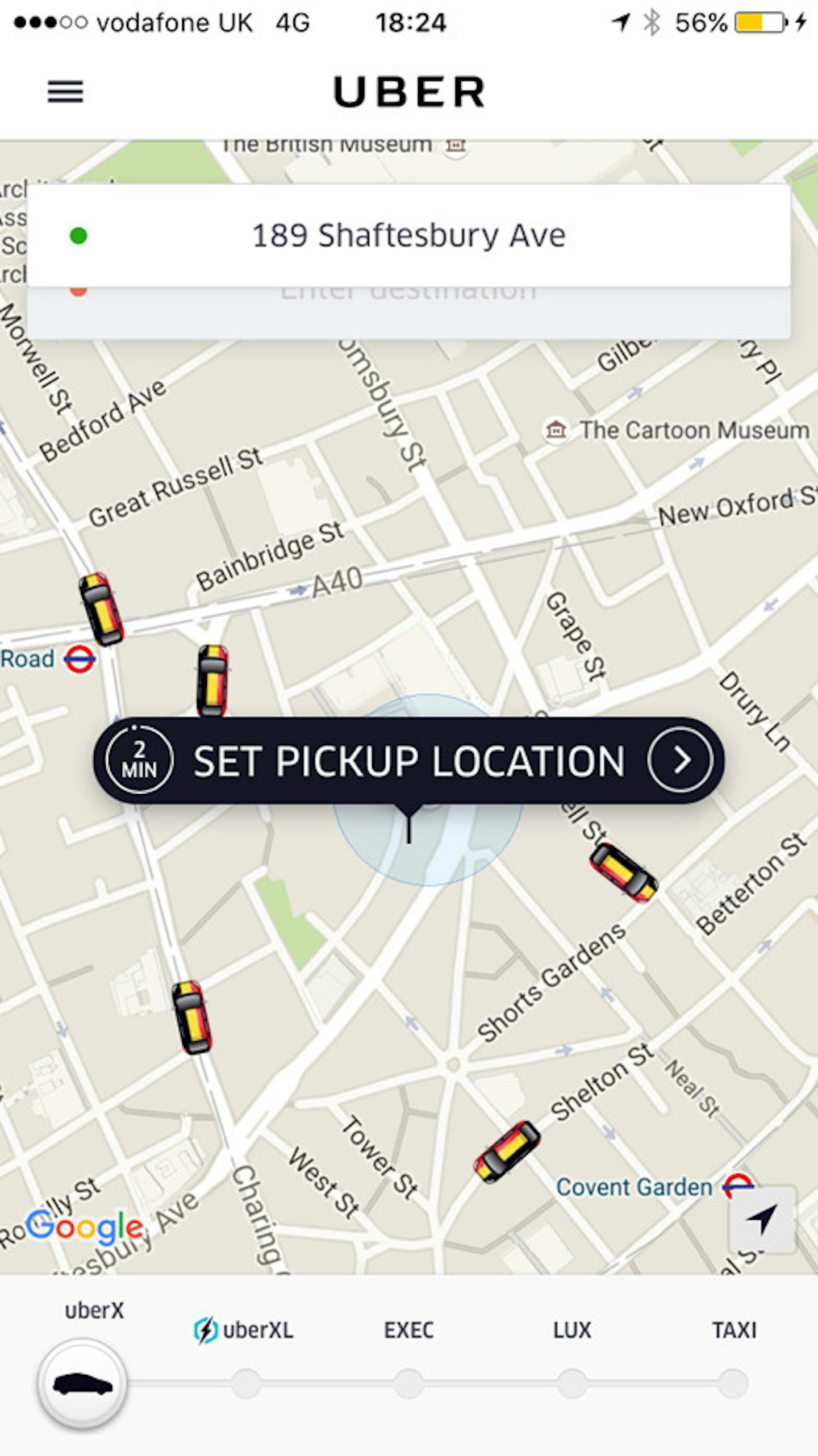

Others shared pictures of themselves in Paris, or memories of times they had visited. Ultimately, both were shows of solidarity on some level with a city under attack, those who had lost their lives and an expression of empathy with the ongoing fear of being affected by a similar attack in the future. Perhaps, because it was so controversial, this time there was noticeable no Belgian flag option available this week. However, Business Insider reports that it is possible to change your profile picture, not throug Facebook but via an external app. The collective mourning has been much more muted, although the anger, shock and sadness endures as the week draws to a close. Uber, however, did impose the Belgian flag on their app.

People Examine and Rexamine Their Views, Some More Loudly Than Others

What follows terrorist attacks is commotion. Both to comprehend what has happened and why, as well as an attempt by many to work out where they stand on associated issues, now, in this post-attack world, on immigration, Islamist extremism, the refugee crisis and social media responses to atrocities.

While some people are rendered speechless and enter into quiet contemplation privately, others voice anti-immigration or Islamophobic sentiment in a very public fashion via social media. Many public commentators, including, of course, Katie Hopkins, while politicians received criticism for posturing - using the attacks on Brussels to talk about how it would be safer is Britain left the EU, they were accused of using the opportunity disrespectfully to shoehorn the murder of innocent people into their own agenda.

Like whiplash after a car accident – society is thrown forwards first, hitting the steering wheel or seat in front before being propelled backwards with a thump, after an atrocity occurs. Isis crack their whip, the initial lash is felt deep, the backlash which follows is frenzied.

Unfortunately terror attacks only serve to reinforce racist, xenophobic or Islamophobic views for those who hold them already. A man from Croydon boastfully tweeted about how he had confronted a Muslim woman in the town and ‘asked her to explain Brussels’. He tweeted that she said ‘nothing to do with me’ and called that ‘a mealy mouthed reply.’ He has since been arrested for inciting racial hatred. Why? Because it’s easier to attack those on our doorstep than Isis themselves – a far off, distant and untouchable threat.

While ‘most of these are short term reactions that go away after a while’ says Professor Brewin, ‘people do start feeling more natiolnalistic, more xenophobic, more supportive of their own institutions.’ Sadly, after the attacks in Paris last November Islamophobic hate crimes did increase, despite the fact that the majority of people who have been killed by Isis are, in fact, Muslim.

Professor Brewin notes that 'members of ethnic miniroties' are often particularly affected by stress and anxiety, 'they are completely appaled by what has happened, but feel their religion or ethnic group is under attack, they might be seen as in someway similar to the perpetrators and they will feel even more stress, possibly, than the rest of the population.'

People Change Their Routes

I tried to get an Uber the morning after the attacks, one of which was on the Belgian capital’s metro underground system, because I was running late. But none were available. Eventually one arrived, ‘it’s a very busy morning’ my driver said, ‘nobody wants to get the tube.’ That was all he said during our journey together, we spent the remainder in silence.

Professor Brewin confirms that people who might not have been directly affected do change their routes after such events. ‘People will change their transport plans, after the London bombings a lot of people stopped using public transport but by 6 months later use of public transport was back to what it was before hand.’ These tend to be ‘temporary changes’ he says, ‘temporary increases in anxiety and stress’.

He points out that the most important thing, however, is helping those who were affected ‘usually countries rely on general mental health services to detect people who have been involved in these incidents and get help for them, but it doesn’t really work in practice. The normal services don’t really work in this scenario, you can get people who are being completely overlooked.’

Because spaces where these attacks take place are so public people may not be recorded as having been there, they may even have walked away ‘it’s a big logistical problem’, he says, ‘from a health point of view, the ones we need to be the most concerned about. Some will recover naturally but others won’t and will need help.’

Rolling News Coverage

As images roll in from the scene of an attack via television news, social media feeds and online coverage how do we begin to decode and digest them? Theorist Judith Butler once wrote that the victims of far-flung horrors ‘are always presented to us as irretrievable’, in other words they’re already dead, gone and lost. We may look on from a distance and ‘shake our heads at their wretchedness but then we sacrifice them nonetheless’. The mainstream reporting and imagery through which we traditionally experienced conflicts, terrors and atrocities was impersonal. Shots of glossy newsreaders cut to presenter-lead tape on the ground in a war zone, shot of war torn villages or debris after the event.

Over the past decade, however, the Internet has reshaped the broadcast model of news. More people have the means to represent themselves, to show their footage and share their views with others. These days the images we trust the most are often the lowest resolution, blurred imaged – captured on someone’s mobile phone, distinctly produced by an individual and not an organisation. We seek these images out, read them as more authentic, more trustworthy.

Today we live in a hyper-connected world where we can view history as it unfolds. We know now, more than ever, that ‘anything’ can happen. We try to console ourselves that it ‘usually doesn’t’ but as soon as we go online or switch on our TVs we are faced with countless exceptional examples of ‘when it does’.

Does this rolling coverage affect the way we respond to and relate to atrocities? Professor Brewin says ‘there is some research showing that watching a lot of television with images of a terror attack is not actually very good for your mental health. It’s quite difficult to understand what’s actually happening here, but certainly we would advise people who have adverse psychological reactions not to watch TV or have updates all the time as to what’s happening.’

In the fifteen years that have passed since New York’s Twin Towers fell the world has changed. There might have been no Isis but there was still terror. Technologically we live our lives differently today. In 2001 there was no iPhone, no Facebook and no Broadband. Today it’s not only by turning on the TV that we make sense of the world around us.

The rhetoric of the long and continuing ‘war on terror’ has neatly divided the globe into allies and enemies, those people should fear and those they should look to for protection – the politicians. The image of a plane flying into the World Trade Centre’s twin towers in September 2001 has become iconic, emblematic and symbolic. It remains as moment in time that history has fossilised around. It stands out as being unlike anything anyone had ever

seen.

Terror thrives on the shock of the new. 9/11 blew open the 21st century for most of the world, changing our notions of home and safety forever. Here we are, now, laid wide open and unsure how to respond to a threat which feels, paradoxically, both inchoate and immediate, far away and close to home.

This is now a hyper-connected digital world where you press one button and everything else reacts: instantly. What we need is time for reflection.

You might also be interested in:

Women Tell Of Islamophobic Attacks As Hate Crinme Numbers Leap

'I've Lost Hope': Muslims Of Reddit Share What's Going Through Their Minds Right Now

Facebook Explains Why Safety Checks Were Used In Paris But Not Beirut

Follow Vicky on Twitter @Victoria_Spratt

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.