It’s my Year 1 sports day, I’m six years old and my dad and I have just finished stumbling through the egg-and-spoon race. We’re laughing and celebrating behind the finish line (a tad unjustified, considering we’d almost come last). I feel a hand on my shoulder, and spin around to see my classmate’s perplexed expression. ‘Why is your grandad allowed to do the father-and-daughter race?’ she asks in the brazen way only a child can. I don’t understand. ‘I am her dad,’ my father proudly interjects, squeezing my hand.

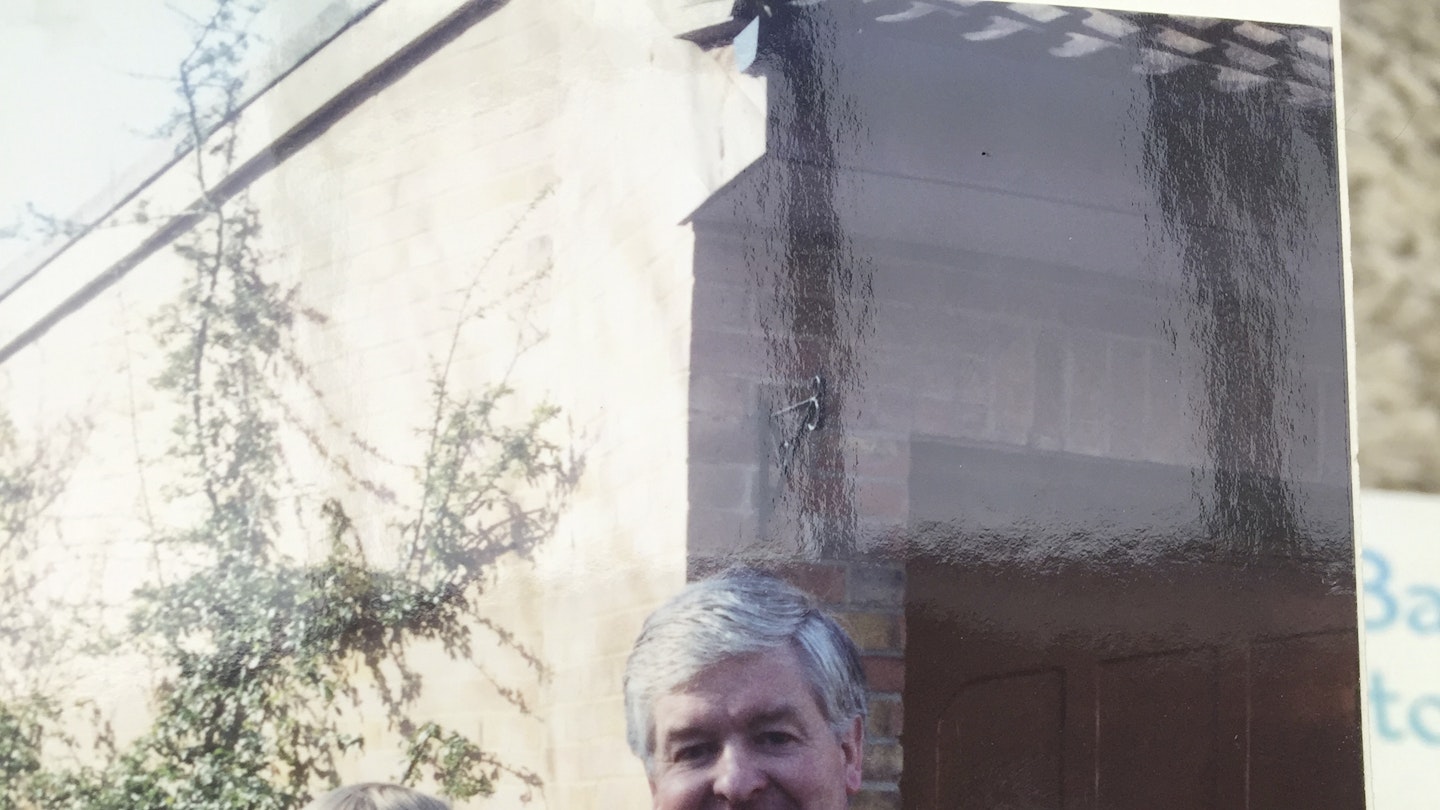

It’s one of my earliest, and clearest, memories. At 57, my dad was the oldest parent there. And at every sports day, school play and birthday party after that. His hair was silver, his brow furrowed. Biologically speaking, my parents were late to start their family – Mum was 39 and Dad was 51. I grew up knowing that my dad was an old dad, but it didn’t bother me. He was always fit, active and spirited, and I never thought of him as elderly.

He was the one who taught me to drive a tractor on his farm in Kent before I’d even sat in the driver’s seat of a car. He was the one who bought me my first legal bottle of wine (and made me scrub the remnants from the carpet in the morning). And he was the one who told me to ‘chin up, my girl – you’re worth more than this’ when my heart was broken.

It wasn’t until I was 12 that his older age suddenly became very real. He was rushed into hospital a week before Christmas, and had to undergo an emergency triple heart bypass. We’re lucky that he survived – a pacemaker now keeps his heartbeat regular – but, ever since then, I’ve been haunted by the thought of his death. I made a vow to myself very young that I wouldn’t leave it as late as my parents did to have children – not only would it mean they wouldn’t have to face the inevitability of my death so young, but I could also do everything in my power to make sure my dad got to meet them.

I am 26. Starting a family in your twenties, however, is becoming increasingly uncommon. The average age for a first-time mother in the UK is now over 30. In comparison to other countries, we are delaying motherhood longer than any other women around the world. If the numbers are anything to go by, my boyfriend and I have at least another four years before we have a child.

And it’ll be another 13 years until I’m 39 – the same age as Mum when she had me. If I wait that long, chances are my dad won’t be around. According to research, a man turning 65 in 2000 could expect to live until he is 83. Dad’s almost 77 – incidentally, the same age as my boyfriend’s grandmother. It’s a bizarre and terrifying type of life maths.

This time of year is always a painful reminder of that narrowing time frame. Of course, I feel incredibly grateful I still get to spend Christmas with two healthy parents who I cherish dearly. But it also makes me feel like I’m wasting time, and there’s a terrible, gnawing guilt that comes with that. I know they want nothing more than to spend Christmas with a grandchild, to see the wonder in their eyes when Santa leaves a dusty footprint in the fireplace, and their overjoyed smile while tearing open an unnecessary amount of toys.

More than ever this year, I can’t help but feel like we’re living on borrowed time – on extra time – that it’s spinning out of our control and, before we know it, it’ll run away with us completely and my dad will miss the opportunity to meet my son or daughter. And to deprive them both of that opportunity terrifies me. Because really, what am I waiting for? To feel ‘ready’? I’m no expert, but I’m pretty sure no mother ever feels completely ready to do something as monumental as bringing a tiny human into the world. I know that I want a family of my own – my boyfriend and I are bursting with love to give a child.

Yet regardless of the love we have to give, I know we’re not ready. For the first time in years, I feel secure in and proud of my career – and though it may sound ignorant, I’m worried about how a child would impact that. And, as my boyfriend says, ‘Where would we put a baby?’ – we’d need a bigger flat and, financially, that’s a long way off.

But despite the practicalities, I do often feel the overwhelming urge to press ‘fast forward’ on life, to race towards motherhood, so that my dad is there to see it all happen. It’s easy for my parents to shrug it off – or, of course, to look as though they’re shrugging it off to protect me. ‘I’ll live until I’m 100, have you seen how long I can hold a plank for?’ Dad says (at least 30 seconds longer than I can).

Despite his health scare, my worrying and telling him ‘I love you, Dad’ at the end of every phone call, here he still is, just a few years shy of 80, making terrible cups of tea, falling asleep during the pivotal moments of BBC dramas, and laughing louder than anyone in the room.

The only thing I know is that I must stop wasting our precious time together worrying about how long we’ve got. If my dad is here to meet my child, it will be one of life’s greatest gifts. But if not, I know what I will do. I will squeeze my child’s hand at every sports day, teach them how to drive (a car this time, I think – sorry Dad) and help them rebuild their broken heart. Because they’re the life lessons my dad gave me to pass on to my family. And, deep down, I know that’s enough.

READ MORE: 'I Won't Have Children Because Of Climate Change'