#MeToo is by no means a perfect movement. In fairness to it, that’s probably because movements that propel social change seldom are. They don’t completely contain an issue, they are never neat and their outcome isn’t always obvious or singular.

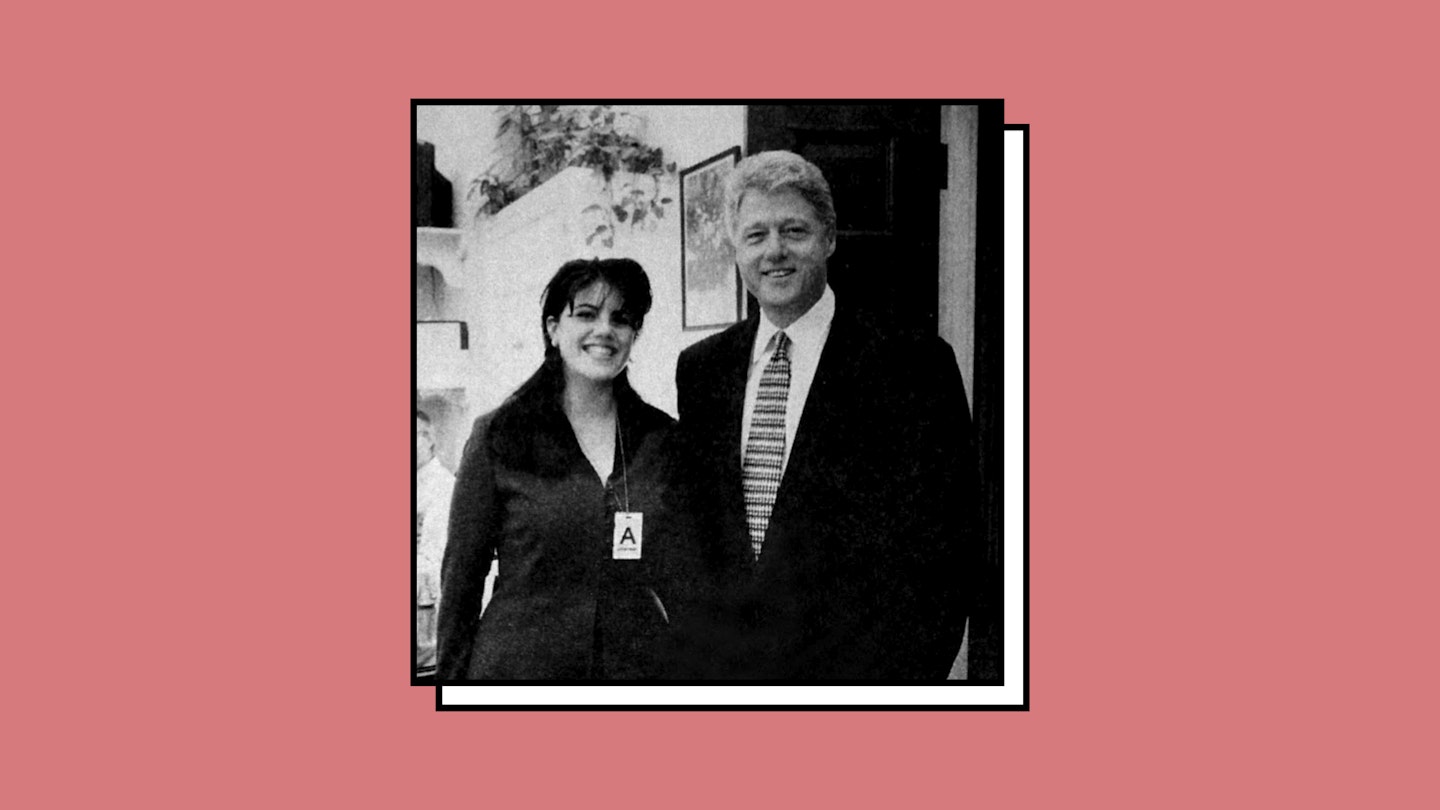

Nonetheless, with every month that goes by its necessity is increasingly obvious. Today it’s Monica Lewinsky’s reassessment of her encounters with Bill Clinton through the lens of the #MeToo movement.

Now, it’s worth point out that it is always dangerous and shaky to use the values and principles of the present to criticize the past. For one, we didn’t see things then as we do now and that’s (generally) a mark of progress. More than this, it’s an anachronism.

I once piped up in a tutorial at university that I didn’t think Mary Wollstonecraft was ‘very interesting’ because she was ‘a bit timid and not radical at all’. My tutor, quite rightly, put me back in my box and asked whether it was fair to make that assessment of her given her historical context. ‘Ought we not’ she said ‘to consider her rather radical not in spite but because of the time in which she was writing and living’.

When it comes to Lewinsky’s experiences #MeToo, for all its flaws, is not so much a stick with which we should beat the past and condemn it for its failings but a yard stick by which we can measure how far things have come. It is proof that there is still work to be done and that even in our very recent past, feminism as a movement failed the very women it purported to be for.

Lewinsky has written, in an essay for Vanity Fair, that #MeToo has forced her to think about consent. She is now not sure that she could have consented to a relationship with former President Bill Clinton while she was a White House intern.

Lewinsky is not abdicated from her part in the affair, nor is she implying she had no agency of her own. What she is doing is acknowledging that the power imbalance between her – then an intern – and him – then one of the most powerful men in the world, skewed their interactions.

‘Now, at 44, I’m beginning (just beginning) to consider the implications of the power differentials that were so vast between a president and a White House intern’, Lewinsky writes. ‘I’m beginning to entertain the notion that in such a circumstance the idea of consent might well be rendered moot. (Although power imbalances — and the ability to abuse them — do exist even when the sex has been consensual.)’

She goes on to write that while there is still much she is unsure of and yet to figure out, she knows ‘one thing for certain’. That is, she says, that ‘part of what has allowed [her] to shift is knowing [she’s] not alone’. ‘For that’ she writes, ‘I am grateful’.

For Lewinsky, as for so many women, knowing that others have experienced something similar to you is empowering. Hearing stories that sound a bit like yours does make you feel less alone. All of this can undo the doubt or self-loathing you have carried around since a bad sexual event – whether it was a sexual encounter that you didn’t quite feel right about or, indeed, more obviously an assault or a rape.

‘I—we—owe a huge debt of gratitude to the #MeToo and Time’s Up heroines’, Lewinsky writes. ‘They are speaking volumes against the pernicious conspiracies of silence that have long protected powerful men when it comes to sexual assault, sexual harassment, and abuse of power’.

Context is everything. Nothing happens in a vacuum. If a Prime Minister or President was now revealed to have had or be having an affair with their 22-year-old intern would we not condemn it as an abuse of power? Would we not balk at the papers who slut-shamed and harassed that intern, as we did when the Daily Mail tried to assassinate Kate Maltby’s character at the end of last year following her accusations against then minister, Damian Green?

In 1998, however, even prominent feminists like Gloria Steinem defended Bill Clinton. She even went as to write an article in which she stood by him for the New York Times which she has since said she would not write if it happened all over again. Despite the fact that by the time the news about Clinton and Lewinsky broke, he had also been accused of sexual harassment by Paula Jones, accused of an extramarital affair by Gennifer Flowers and allegedly used Arkansas state troopers to cover up numerous affairs, Steinem still defended him.

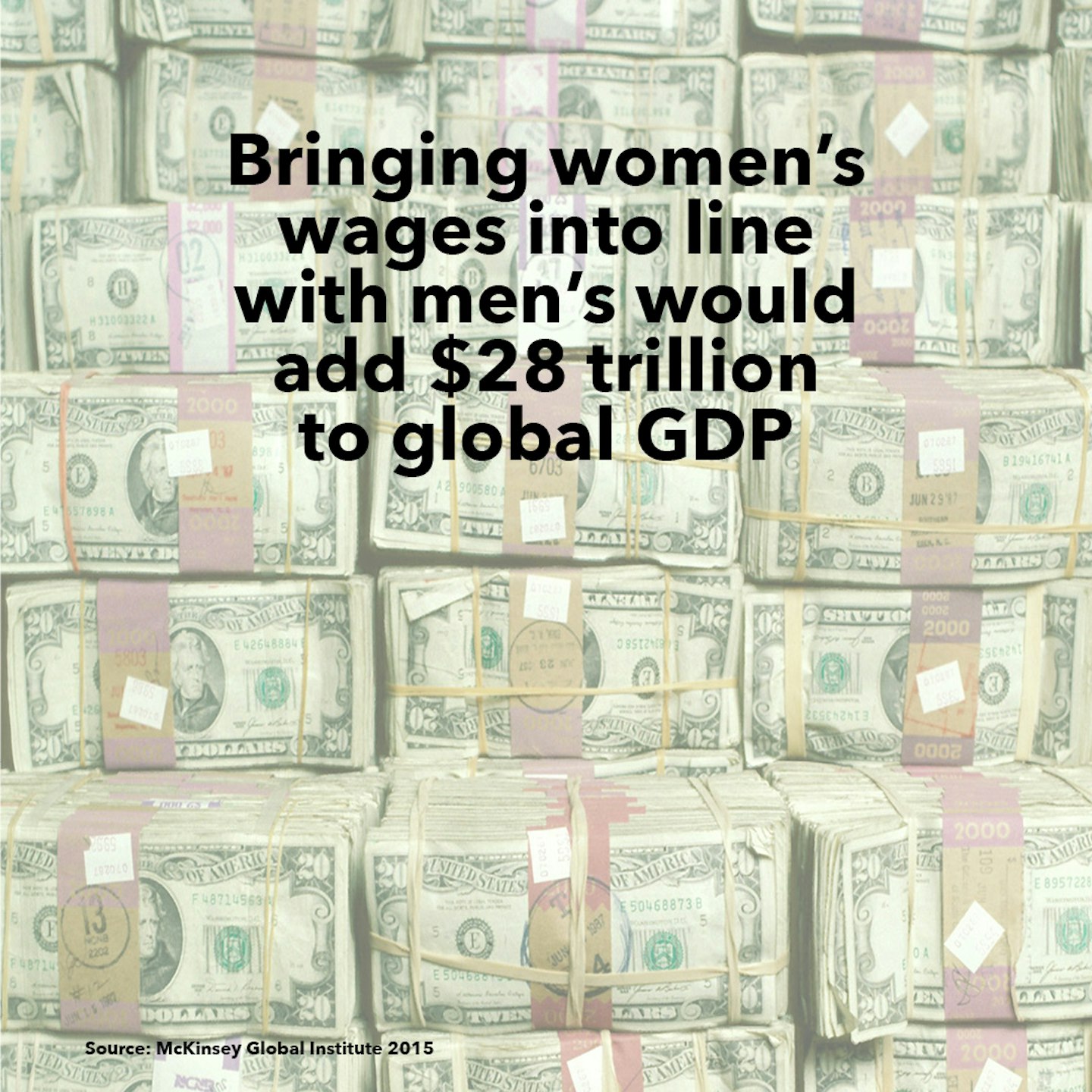

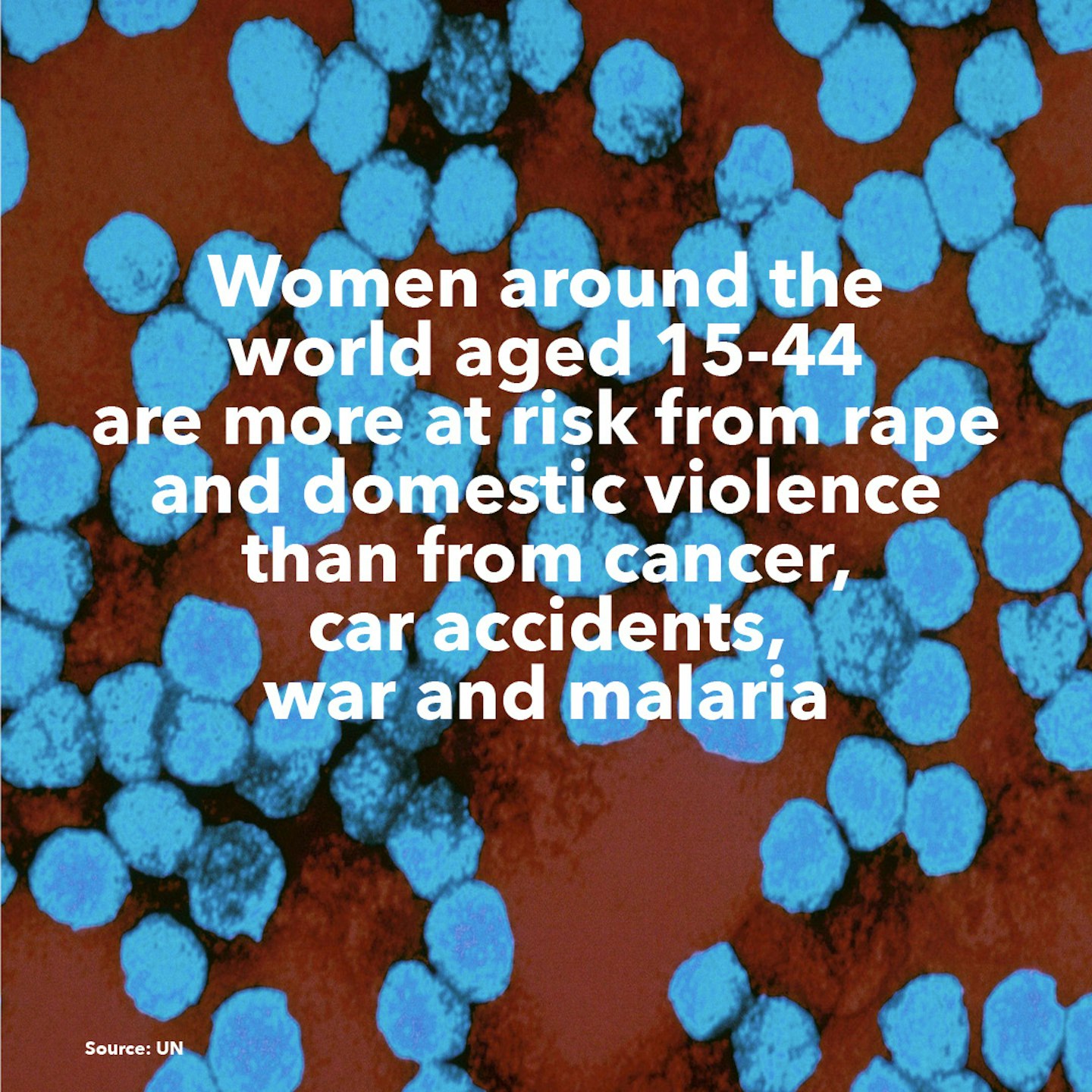

READ MORE: Facts About Women Around The World

Debrief Facts about women around the world

1 of 18

1 of 18Facts about women around the world

2 of 18

2 of 18Facts about women around the world

3 of 18

3 of 18Facts about women around the world

4 of 18

4 of 18Facts about women around the world

5 of 18

5 of 18Facts about women around the world

6 of 18

6 of 18Facts about women around the world

7 of 18

7 of 18Facts about women around the world

8 of 18

8 of 18Facts about women around the world

9 of 18

9 of 18Facts about women around the world

10 of 18

10 of 18Facts about women around the world

11 of 18

11 of 18Facts about women around the world

12 of 18

12 of 18Facts about women around the world

13 of 18

13 of 18Facts about women around the world

14 of 18

14 of 18Facts about women around the world

15 of 18

15 of 18Facts about women around the world

16 of 18

16 of 18Facts about women around the world

17 of 18

17 of 18Facts about women around the world

18 of 18

18 of 18Facts about women around the world

In that 1998 essay, Feminists and the Clinton Question, she wrote ‘if all the sexual allegations now swirling around the White House turn out to be true, President Clinton may be a candidate for sex addiction therapy’ She continued, ‘even if the allegations are true, the President is not guilty of sexual harassment. He is accused of having made a gross, dumb and reckless pass’.

Fast forward 20 years. Speaking to the Guardian at the end of last year, Steinem said that while she did not regret her defence of Bill Clinton at the time she would perhaps not make it again. ‘We have to believe women’ she said ‘I wouldn’t write the same thing now because there’s probably more known about other women now. I’m not sure’. Steinem said all of this on the red carpet of an annual comedy benefit for the Ms Foundation for Women, of which she is a founder.

The way that Monica Lewinsky was treated by women everywhere as well as by the media at the time is as significant as what actually happened between her and Bill Clinton. If the same thing happened today it’s hard to imagine anyone questioning whether it was gross misconduct on the part of the person in power.

Were the Lewinsky/Clinton affair to happen now I like to think we would ask not whether she consented but how consent works in the context of the power dynamic between a president and his intern.

‘What you write in one decade you don’t necessarily write in the next’ Steinem said. By the same token, what you might consent or think you have consented to in one decade, you wouldn’t necessarily give an affirmative ‘yes’ to in the next. That is as true for Lewinsky as it is for me and countless other women today, and there can be no doubt that #MeToo has helped us all to realise that.

And so, therein lies the potential power of the problematic#MeToo. At its best, it is a moment of reckoning, a yardstick for progress and a reminder that there is still more to do. It is, above all, a way of having a global conversation and, eventually, pushing for further legislative change and better sex education so that, one day, consent will no longer be up for debate.

Follow Vicky on Twitter@Victoria_Spratt

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.