For me, 2014 has been defined by the Ebola crisis. I’m the BBC’s global health correspondent, and I started covering the Ebola outbreak nine months ago, at the end of March. We started noticing a cluster of deaths from haemmorhagic fever and thought it was important to cover them, but at this stage, Ebola wasn’t world news. But it’s dominated the headlines and the lives of the families of those who have suffered from it.

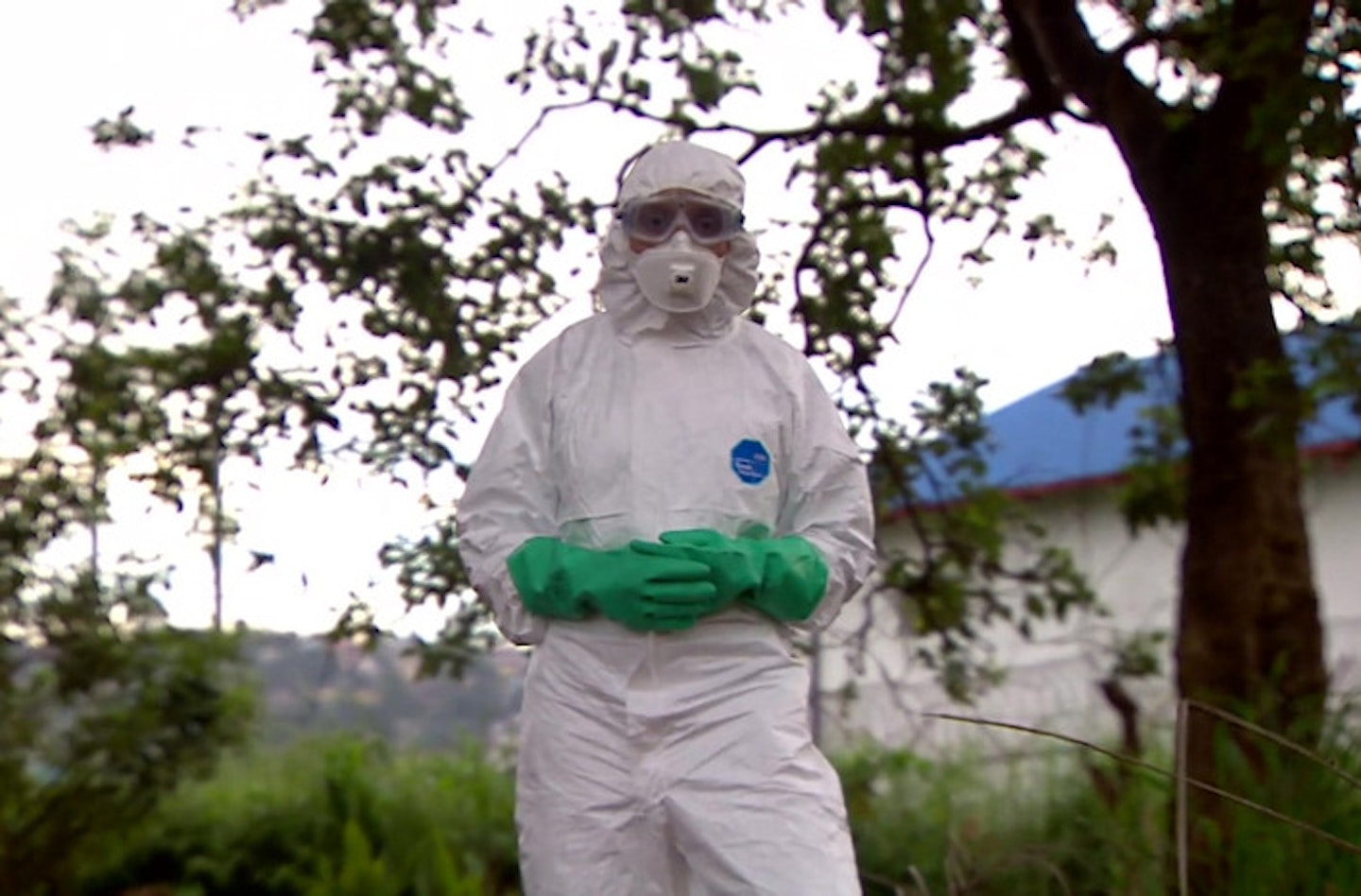

With the BBC, I’ve been out to Guinea twice and Sierra Leone three times. We liaised with NGOs and charities like the Red Cross and Medicins Sans Frontiers so that we could cover the outbreak in a sensitive way that was useful to local communities – we didn’t just show up and get our cameras out. As a reporter, you have a responsibility to gather and spread information in a way that helps and educates as many people as possible, both internationally and locally.

We met people who were scared. In the first place we went to, a village in Guinea called Kollobengou, and there was a lot of mistrust of both our team and the health workers we were travelling with. It was hardest in rural areas, who weren’t watching what was happening on TV, or seeing it in newspapers. Health workers who have been going into these very remote communities have told me people often believe it was the medics themselves bringing the virus into their villages, because their arrival coincided with breakouts. The feeling of fear was so strong that you could almost touch it. One of the first things the health workers did was to introduce the community to an Ebola survivor, who spoke to them and told them that you can survive the virus if you get treatment early.

It’s difficult to believe, but it’s actually quite hard to catch Ebola. It isn’t airborne, and it’s only passed on if you touch someone who is sick and showing symptoms. In terms of risk to us, we had to make sure we weren’t touching people who weren’t sick, which was pretty easy to do. We’d usually shake hands with the people who we were interviewing, but we stopped doing that. However, in the countries where Ebola has become widespread, there was usually a longstanding cultural practice of washing the bodies of the dead.

READ MORE: Here's The Reality Of Working On The Front Line Of The Ebola Crisis

Families and loved ones would prepare their deceased relatives for burial, and come into contact with their blood and fluids. In any country, the way you deal with the body of a deceased relative comes with its own set of important rituals. Because this practice was such an important and long standing tradition, it’s been difficult to get across to everyone that this ritual is spreading the virus.

I was enormously lucky to have enough support and information to stay safe, but understandably, some of my friends and family were really anxious about spending time with me when I came back to the UK. In August/September time when infections were reaching the US, the UK and Spain, I noticed some people were particularly concerned about meeting up with me. One friend of a health worker who I met in Sierra Leona was told she couldn’t come to a family Christmas dinner, because the other guests were worried that she might be contagious. Everyone who has been out here understands why people back in the UK might be concerned.

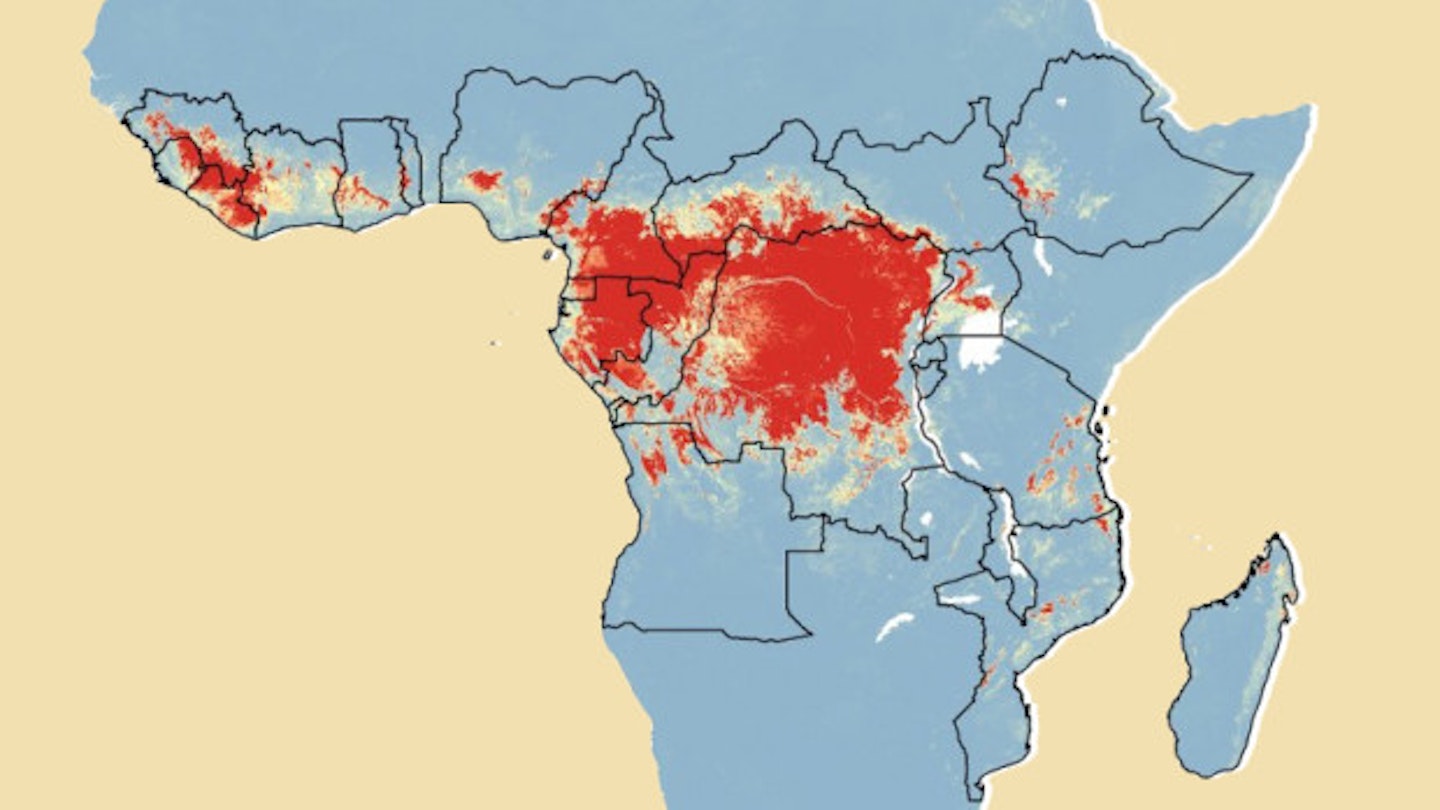

There’s a big problem with stigmatising Africa as a continent. I have heard stories about friends of medics and even some hotels voicing concerns over Ebola about people returning from South Africa when Ebola is nowhere near South Africa. I think that we’re closer to West Africa in the UK than some parts of South Africa are. Also, the people who really do need help feel stigmatised and isolated. British Airways and Emirates are among airlines who have cancelled their direct flights to Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia. You talk to people on the ground and they say ‘We feel isolated, and the world’s scared of us’. They need help, and they’re being told they’re dangerous and made to feel that they should deal with it on their own, when the last thing they need is stigmatisation and isolation.

There’s always a danger of painting an entire country as victims, and giving the impression that it’s down to Western countries to come in and save the day. I think that more people need to know how many West Africans are working to contain the outbreak. From the outside it looks like lots of other countries are rushing in to help, but the truth is that the bulk of the high risk jobs are done by West Africans - they’re the hygienists, doctors, nurses and gravediggers.

The good news is that the outbreak seems to be slowing down. Recently the World Health Organisation told me that we’re not seeing the same huge numbers of cases that were coming through in September, and in Liberia, the figures are slowing - although there’s more of a mixed picture in Sierra Leone and Guinea. No-one saw an outbreak on this scale coming, and it’s equally hard to say when it will end. Ebola has been around for 40 years, and it’s taken this outbreak to force new developments in vaccines and cures. We’re seeing new treatments and a couple of vaccines in the pipeline, so although it’s impossible to confirm, the hope is this outbreak will end in 2015 . However, this will only be possible if we all educate ourselves on how the disease is spread, and how the risks can be managed. The chances of it affecting anyone in the UK are incredibly low, but as global citizens we have a responsibility to find out as much as we can, and not give into a fear which is only going to further isolate the people who are really suffering.

**Liked this? You might also be interested in: **

Chris Brown Isn't The Only One Making Stupid Jokes About Ebola

Tulip Mazumdar is the Global Health Correspondent for BBC News. Follow her and find out more about her work @TulipMazumdar

As told to Sophie Wilkinson. Words: Daisy Buchanan

Pictures: Courtesy of BBC

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.