Browsing Facebook albums of selfies taken next to the Burj Khalifa, a family-funded trip to go snorkeling in Hurghada, saving your hard-earned cash for a trip with mates to check out Marrakech’s best souks, stopping over in Singapore on the way to somewhere else and reveling in all the shops; we’ve all seen a bit of Dubai, or Egypt, or Morocco, or Singapore, or wherever. They’re just sunny holidays a long-ish flight from the UK, right? Wrong. Because the moment you step into these countries, you’re stepping into jurisdictions where it’s illegal to be gay. If you're not LGBT yourself – you probably have a friend, family member or acquaintance who is, right? That sunny holiday in the sand you were just imagining kind of loses its gloss when you remember that you’re going to a country where simply showing affection to another girl could get you in legal trouble, right?

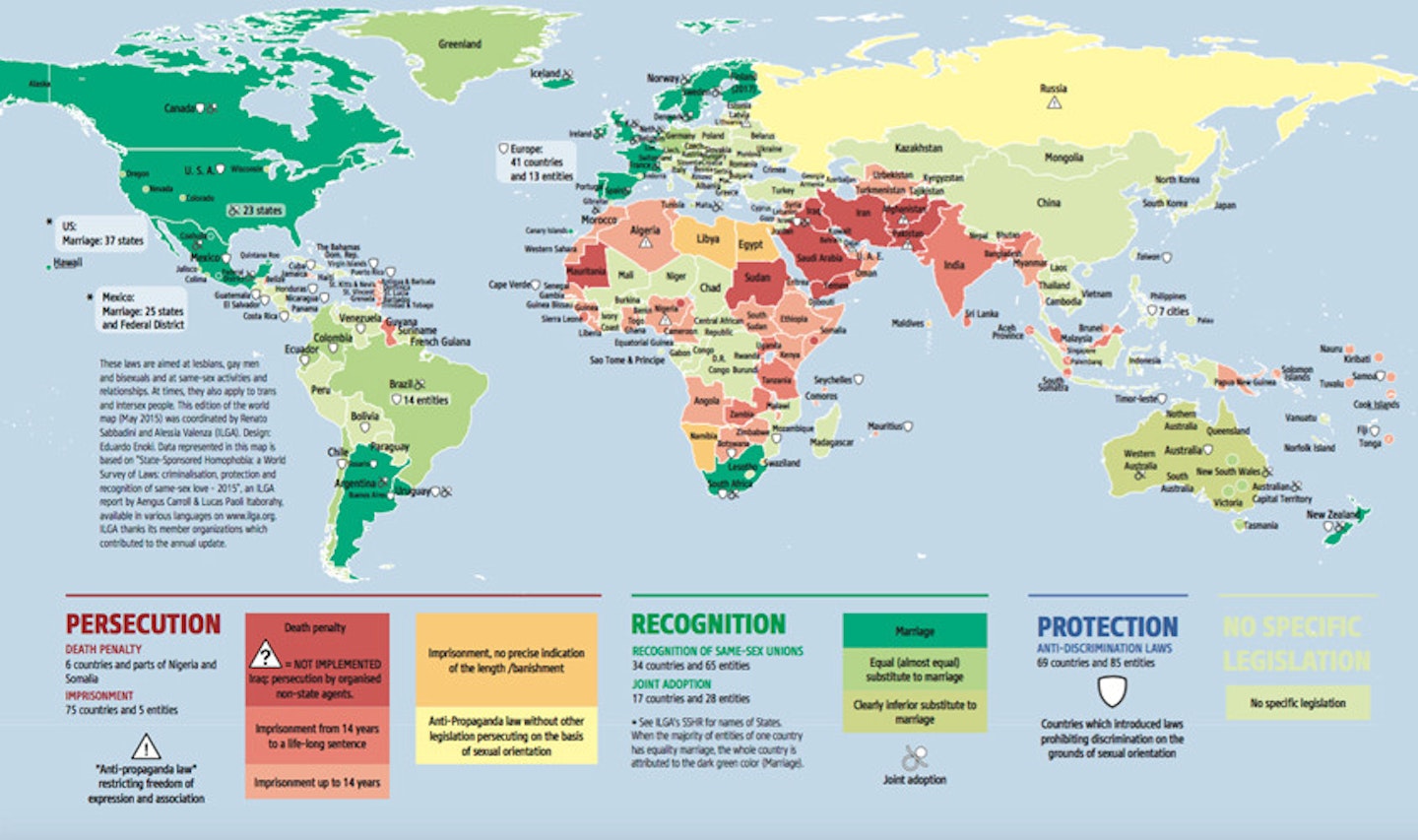

Earlier this month, the Government emailed the authorities of 70 countries to ask if they would recognise the rights of same-sex couples who have married over here. At present, 78 countries in the world have made it illegal to be gay, so are pretty far off getting this polite request from the British powers-that-be. But so many of them – Dubai, Morocco, Barbados, Jamaica, Kenya, Singapore and Sri Lanka – are still travel destinations for Brits.

So what are the ethics of travelling to a gay country? We spoke to a lesbian couple, Alice Ali, 27, and Tovah Nosti-Menéndez, who visited Morocco for New Years Eve 2015, just months after 69-year-old Ray Cole, a gay man from Kent, had been imprisoned in Marrakech for the crime of being gay.

‘We realised it would be a bit of a problem when we read in a travel guide that Moroccans don’t believe in gay people, but it is illegal and you can go to jail for it. I wasn’t quite scared, just a bit more wary,’ Tovah tells The Debrief.

It wasn’t Alice’s first time to the country, but this time she was ‘much more anxious,’ she tells us: ‘Maybe I was a bit older and knew about the severity [of its anti-gay laws] a bit more, but it’s different if you’re just gay there or if you go with a partner.’

The first place we stayed in, I think the guy suspected we were together. We got assigned a room where no-one else was, at the very top of the riad

The biggest symbol of their lack of freedoms as a couple was when booking hotels: ‘I guess everyone has their specific definition of [persecution] but for us it would be something as simple as a double bed,’ Tovah says.

Alice explains: ‘No straight couple would get questioned whether they would want a single of a double, even if you were brother and sister you would probably be given a double. The first place we stayed in, I think the guy suspected we were together. We got assigned a room where no-one else was, at the very top of the riad [a traditional Moroccan dwelling] where they hung the washing. It wasn’t a proper room and it wasn’t what we’d booked but I had no consumer right there, I couldn’t have said: “this isn’t what I paid for,” I didn’t want to cause a fuss, I didn’t want to mention the fact we had two single beds.’

Outside, even away from what Alice calls the ‘hustle’ of the souks, when they spent a week in the isolated Western Sahara, they couldn’t be open with one another: ‘Although we were staying in these camps and they were liberal in feeling, they were still run by Moroccans,’ Alice says, ‘So we chose not to come out. We had to run round this beautiful beach to find a hidden area, like, walking up a hill to try and be alone,’ Alice tells us.

Tovah agrees: ‘That was the most difficult thing and it was really, really frustrating for me.’

There was a tiny upside: ‘Because the public affection has been removed from the way we interact, it meant that we talked a lot more – to each other and other people – and we observed things a lot more,’ Alice says.

‘There was less of that distraction.’ Tovah explains.

It’s an exercise that could probably be patented, packaged and sold to troubled married couples as relationship therapy, but it’s hardly ideal for a holiday for a young couple in love, is it?

You’re forced to cover up your sexuality up for safety and we can cover up the fact that you’re gay, but you can’t cover up the fact you’re a woman.

Both agreed that they faced more problems as women than as gay women: ‘I wasn’t really thinking in the sense of “I’m gay in this country,” it was more like “as a woman in this country” like, I really haven’t got a voice, you know?’

Alice agrees: ‘You’re forced to cover up [your sexuality] up for safety and we can cover up the fact that you’re gay, but you can’t cover up the fact you’re a woman. So dealing with the consequences of that becomes the priority.’

As for Tovah, being Afro-Caribbean made the catcalls she received even more different: ‘I was a victim of the normal kind of “She’s a tourist, she looks foreign, she’s white, she’s blonde, she looks different.”’ Alice tells us: ‘But they thought Tovah was Berber [a group of people indigenous to north Africa]'

'They were making jokes at me that they thought I would get, they were kind of treating me like they knew me,’ Tovah adds.

The Home Office advises that people who are LGBT learn a lot about the country and think before they travel, telling The Debrief: ‘Our travel advice is based on objective assessments of the risks to British nationals. These assessments are made by drawing on expert sources of information available to the government including intelligence, local knowledge, and experience of our overseas staff. Advice is under constant review, especially for volatile regions or developing crises’

But what if you’re straight and want to show some solidarity to gay people who travel and live in countries where being gay is illegal? What are you meant to do?

The rules on gay people can be confusing, says Alexandra Green, 28, who went to Qatar to work as creative director of Doha’s International Day, who only agreed to travel there on the condition of contributing to culture: 'I wouldn’t have gone out of there to work in insurance or something; it’s nice to work in a place where you do come up against a lot. It’s the most challenging job I’ve ever had, but it’s worth it to see the amount that people get from it, just moving and dancing. This is a country where women doing cartwheels – showing their ankles – is socially unacceptable.’

My travelling there does nothing to express the sadness and anger I feel about how LGBTQ people are treated in this part of the world.

What happens if you have no say in going? Like, it's a family holiday and you don't want to kick up a fuss? Rachael Scarsbrook, 20, feels pretty guilty that her annual family holidays are to Egypt; ‘As much as I detest the way people who identify as anything other than straight are treated, the holidays there; for me personally, are wonderful... It's hypocritical to say I would go back, because I realise that it makes me part of the problem in some sense. My travelling there does nothing to express the sadness and anger I feel about how LGBTQ people are treated in this part of the world.’

And though Annabelle Collins, 23, visited Russia – where ‘gay propaganda’ is banned – as a tourist, she’s decided against returning: ‘I felt torn when planning my trip and but ultimately the reason I was going – to visit boyfriend and friends – was enough to make me go ahead. Now, I wouldn’t feel comfortable going.’

‘I think it is important to be aware of the human rights situation when travelling somewhere, especially as a tourist.’

It makes you wonder why people don't just boycott these countries. Alice says 'I didn't always feel comfortable putting money into an economy that treats its citizens badly.'

If boycotting countries which don't allow equality was the solution, we'd never travel anywhere

But a representative from The Kaleidoscope Trust, a UK based charity working to uphold the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans people internationally, tells The Debrief that no, a boycott isn’t the answer: ‘To be a good global citizen, we’d encourage people to research what LGBT people that live in the country think about tourism and be led by what they suggest. Very often, even in what we think as the most “dangerous” places, LGBT people welcome international tourism as it is can be an important industry in their countries.’

And besides, the UK is hardly a shining example of equality. Galop, a charity which helps victims of homophobia, also told The Debrief: ‘Plenty of gay people might not even feel safe in the UK’ – when statistics show that one in six LGBT people in the UK have been harassed or assaulted, we can hardly judge other countries.

Just as Alice and Tovah found their gender much more of a catcalling point than their sexuality, it's worth looking at how safe it is to travel, simply as a woman. If boycotting countries which don't allow equality was the solution, we'd never travel anywhere, as 135 out of 143, that's, 90% of countries surveyed by the World Bank have sexist laws built into their legislation or constitution.

So long as people will be identified by others gender first, sexuality second, the whole argument of ethically avoiding a country falls flat.

So what's the solution? Don’t isolate the gay people – or women - suffering inequality. Book that holiday, but as everyone we spoke to recommends, learn as much about it and its human rights records before getting there.

Liked this? You might also be interested in:

Valentine's Day Isn't All Roses When You're In A Lesbian Couple

Stupid Questions You Get Asked About Sex When You're Bisexual

Why The Search For The Gay Gene Is More Important Than You Think

Follow Sophie on Twitter @Sophwilkinson

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.