Earlier this week Brazilian footballer Bruno Fernandes de Souza, who was convicted of having his former girlfriend, Eliza Samudio, abducted, murdered and fed to a pack of dogs, made headlines again after he was signed by football club Boa Esporte despite having only served part of his prison sentence.

Today, it has been revealed that the central character from one of those cases, footballer Adam Johnson, has been denied leave to appeal against his child abuse conviction. Whenever a high profile case like this surfaces it strikes a chord with us all. Why? Because it’s not just footballers who rape, abuse, assault and incite misogyny and violence against women. It’s because in the UK we all know someone who has been assaulted and for women in Brazil it’s likely they know someone who has suffered a far worse fate (in Brazil, according to Amnesty International, lethal violence against women is increasing).

Whether it’s the alleged abuses of Hollywood Academy Award winners, a debate about whether or not a known rapist should be given a platform at a high profile women’s festival in London or a public official blaming the victims of sexual assault in India, there is an ongoing global conversation about attitudes and responses to sexual assault and rape that never goes away.

Just to recap, Johnson was jailed for six years last Marchafter he was found guilty of sexual activity with a 15-year-old girl. This ruling has come from the Royal Courts of Justice and was decided last Thursday, where three judges rejected this latest appeal and bid to reduce his sentence.

Johnson admitted to grooming his teenage victim and one charge of sexual activity, but jurors found him guilty of another charge of sexual touching and not guilty of one other charge. Appeal judges have now upheld his conviction at the highest level, saying that while it might be ‘stiff, even severe’ they do not consider it ‘manifestly excessive’. In a statement, Durham Police have said ‘this has been a protracted case for the victim and, indeed, everyone connected to it. Hopefully, this will now draw a line under it and we can all move on.’

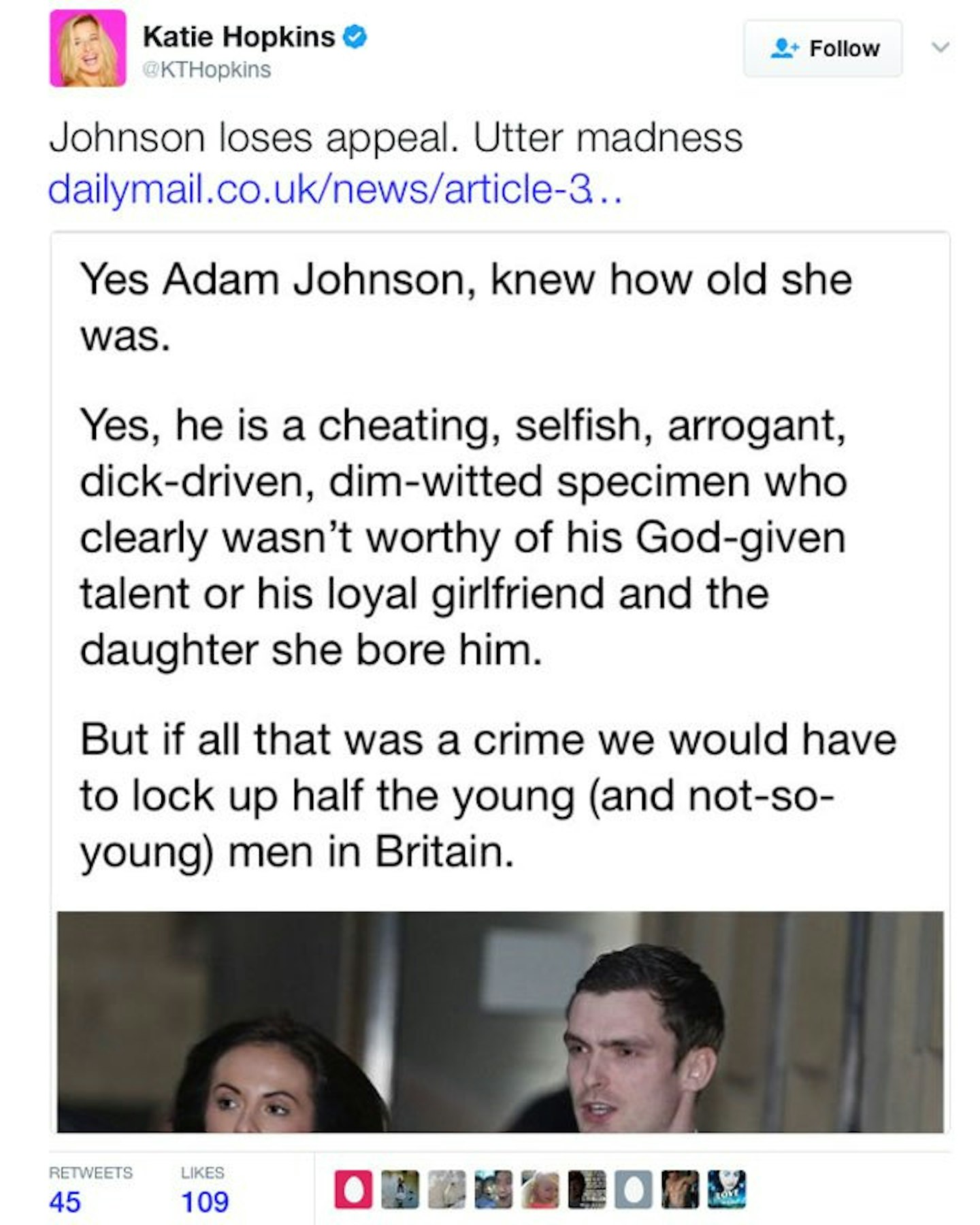

Prior to beginning his prison sentence,Johnson held an ‘all-night’ rager at his mansion in County Durham. After he was found guilty at Bradford Crown Court his barrister made it clear that Johnson intended to appeal the guilty verdict, which was returned with a majority of ten to two by the jury. And yet, despite all of this, somehow commentator Katie Hopkins felt able to compose a tweet which read 'Johnson loses appeal. Utter madness', a tweet that was then shared by the footballer's sister.

Johnson’s case, along with that of Ched Evans who was acquitted of rape charges during a retrial at the end of last year, has fuelled ongoing conversations about rape, consent and how our legal system deals with both. The admission of Evans’ accuser’s sexual history as evidence in court sparked not only public but political and legal outrage.

There’s a common thread to the aforementioned high-profile cases: in each and every one we only know the name of the man involved. In each and every one we hear about what happens to the man after the trial, we hear about their appeals, people ponder over their futures.

What of the women involved? What of the accuser in the Ched Evans case who has received abuse on social media and moved house multiple times? What of the young woman in the Adam Johnson case who, despite his conviction being upheld, is still having doubt cast over her integrity? What about the women who don’t receive Academy Awards for their work because they’ve left jobs after being allegedly assaulted? And what about Eliza Samudio? She has no future; it was taken away from her.

Of course, these cases are not directly linked. The people involved aren’t part of the same secretive mob, gang or clan but we shouldn’t kid ourselves into talking about them as though they aren’t related.

Last year a European Commission report on gender-based violence asked 30,000 EU citizens whether they thought that sex without consent was acceptable in certain circumstances, such as when a woman is wearing ‘revealing’ clothing. Over a quarter of people asked said yes, they thought it was acceptable. This report also found that just over 10% of people asked thought that sex without consent could, potentially, be justifiable if the victim had voluntarily gone home with the aggressor, was also wearing ‘revealing clothing’ and hadn’t said ‘no’ clearly enough. The results varied from country to country, with Spain and Sweden among the least likely to say rape could ever be justified, Romania and Hungary among the most likely to think it could, sometimes be justified, and the United Kingdom coming in somewhere in the middle along with France and Italy. Here, 22% of people asked said that they thought rape was acceptable in some circumstances, with 12% of people saying that excessive drinking or drug use could make non-consensual sex acceptable.

There’s a message constantly being sent out about violence against women, sexual assault and rape and it’s this: the unjustifiable can be justified, the indefensible can be defended and the unacceptable can be accepted. Women aren’t believed, women don’t matter and the men who abuse, assault, rape and murder them are, almost always, entitled to second chances.

There is a common thread here, one which can be traced across the world, and it is the reason that we must keep having conversations about consent, rape and violence against women in terms of what it means for…women.

You might also be interested in:

Follow Vicky on Twitter @Victoria_Spratt

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.