This month sees students around the UK eagerly trundling off for new terms at university, many for the very first time. But as well as fun-packed freshers’ weeks, socials and lectures, there’s another experience many are unwittingly signing up for – sexual violence.

According to a recent survey by campaign group Revolt Sexual Assault, 70% of female students in the UK say they have experienced sexual violence at university (a shocking 62% of all students). Groping and unwelcome touching in a sexual manner was the most commonly experienced form, with over half of students revealing incidents took place in either their halls of residence or a university social space.

‘We know the true number of incidents of sexual harassment to be far higher than the number reported by universities,’ agrees NUS Women’s Officer Sarah Lasoye. ‘Our research shows that the number of incidents reported is typically lower than 10%, but that one in seven female students experience serious sexual assault at university. These figures also show that the number of reports that are subsequently investigated is woefully low. In addition, support made available to survivors of sexual assault is often inadequate, if it exists at all.’

Trying to change all that is Hannah Price, 24, a former student at Bristol University and founder of Revolt Sexual Assault. In 2015, Hannah was raped by a fellow student. ‘I was about to leave a society night out when a guy I knew offered to walk me back to my student house as he was going that way,’ she explains. ‘It’s what we’re taught to do – always get a guy to walk you home – so I agreed, and when we got to mine he asked if he could grab a glass of water, as he wasn’t feeling well. I said OK, but then he started coming on to me. Within seconds, he became aggressive and raped me before leaving. I found out later he didn’t live anywhere near me.’

Realising there wasn’t any information or help available on the university website, Hannah panicked. ‘I knew I was going to see him all the time on nights out, in the supermarket, in lectures... I felt like I had no option other than to pretend it hadn’t happened,’ she says. As a result, Hannah decided not to report the rape, and is currently waiting for therapy, having been diagnosed with PTSD.

But she did know she wanted to do something– especially when another university friend confided in her about her own experience. ‘We were chatting in my bed after a night out, and she told me she’d gone home with a guy we both knew,’ explains Hannah. ‘They’d had consensual sex and she’d gone to sleep, but she woke in the night to find him having sex with her again. At the time, she wasn’t able to see that that was rape.’

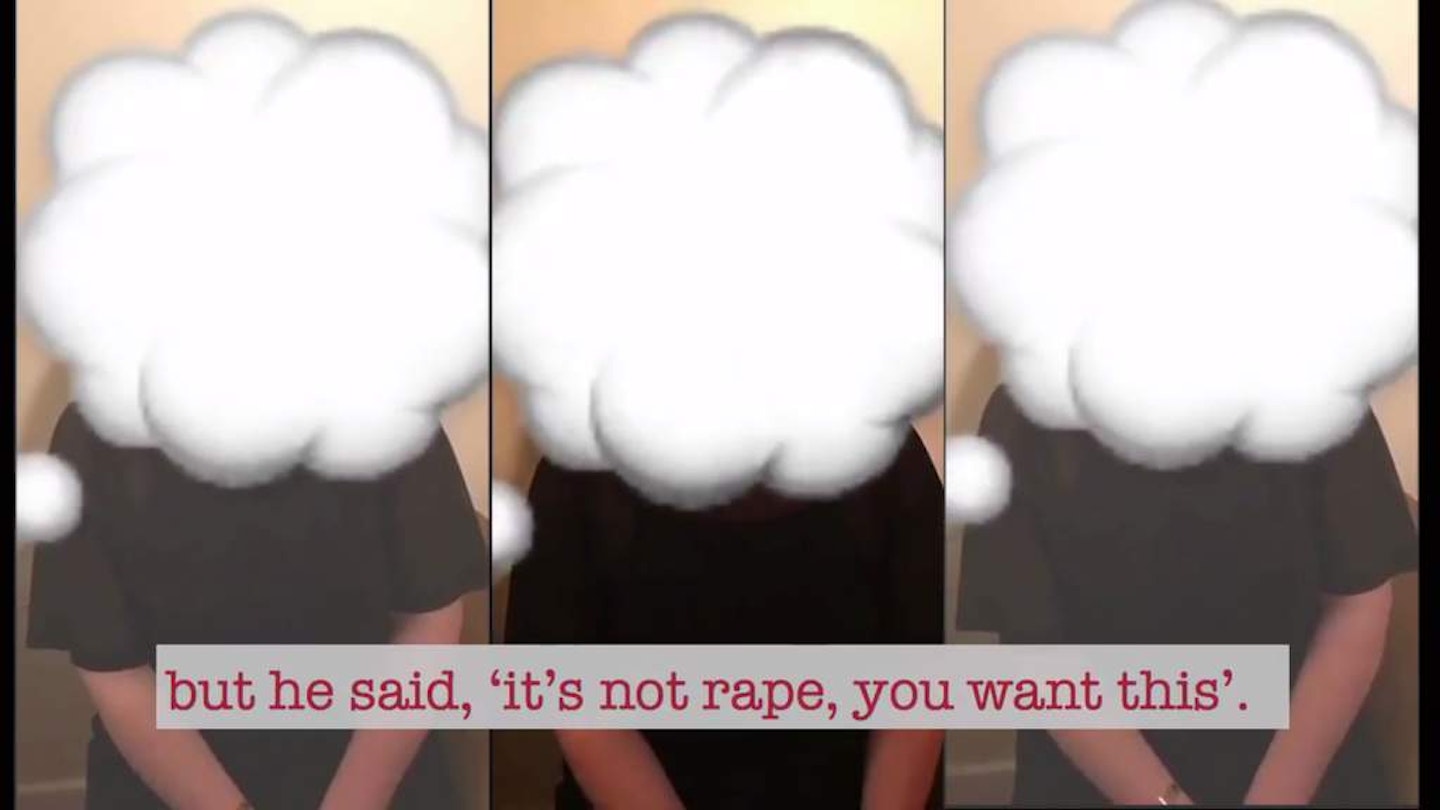

So, last April, Hannah came up with a plan. ‘I wanted to give people the chance to speak out about their experiences. Being groped or catcalled daily meant my friends and I had stopped talking about sexual harassment – even among ourselves – because it had become so normalised. It wasn’t a conversation that was happening, and I knew it should be. I’d seen two rape survivors in India using Snapchat as a way of talking about their experiences while remaining anonymous. I thought it was a great way of sharing stories in a really humanising way, so I started requesting Bristol students to share theirs.’

Within a few weeks, Hannah had filmed dozens of testimonies from fellow students detailing their experiences at the university, which she shared on social media and the campaign’s website. After six months she decided to share her own, too, waiving her anonymity. Her video went viral, and soon people from universities all over the UK were getting in touch.

‘We get hundreds of messages saying, “That happened to me,”’ she explains. ‘Some are first year students, others PhD or graduates – the scale of it is overwhelming. One girl came in to do hers and she had a list in her hand, asking, “Which instance do you want me to talk about?”’

Using Snapchat has helped fuel the outpouring of stories, says Hannah. ‘I wanted to give people the chance to speak out in a way that was familiar to them, and Snapchat is that platform for Millennials. Plus, it gives the power back to the person telling their story.’ The filters allow you to alter your appearance and voice, so you can speak anonymously. ‘It can be jarring seeing emojis and filters being used about such a serious topic, but it’s made it easier for people to come forward – and made it harder to ignore the issue.’

The next step for Hannah is making a tangible change. ‘We were angry and our campaign made a lot of noise, but now we’re trying to work out a solution. Our hashtag has evolved from #itsrevolting to #changeiscoming – we’ve pointed out the problem, and we’re now working out how to move forward. We want universities to take responsibility and be proactive when it comes to procedures and policies – they didn’t see it as “their” problem, but it absolutely falls under students’ wellbeing.’

The extent of the issue has given rise to many campaigns to try and solve it. Pavan Amara runs The MyBodyBack Project, a support service empowering women who have experienced sexual violence, and she sees a huge number of students getting in touch. ‘The difference with those who have been attacked at university is that they are often far from everything familiar,’ she explains. ‘They’re not in a routine or surrounded by stable friendships or relationships. They often have little money, and it’s the first time they’ve been away from home and many don’t want to appear to have “failed”. I’ve heard plenty of students say they didn’t tell their parents because they didn’t want them to think they “couldn’t handle” adult life.’

For Amara, that’s a worrying thing to hear. ‘I think it highlights, unfortunately, that women of all ages will find ways to blame themselves rather than the perpetrator,’ she says. ‘I regularly find myself reminding women that it’s nothing to do with their ability to “handle life”. Adult life is about things like bills, choices and decisions, not being sexually assaulted and having to cope with the indescribable consequences. It should not be something any woman has to deal with. Unfortunately, many of us do.’

If you want to help fund Revolt Sexual Assault's national campaign, click here