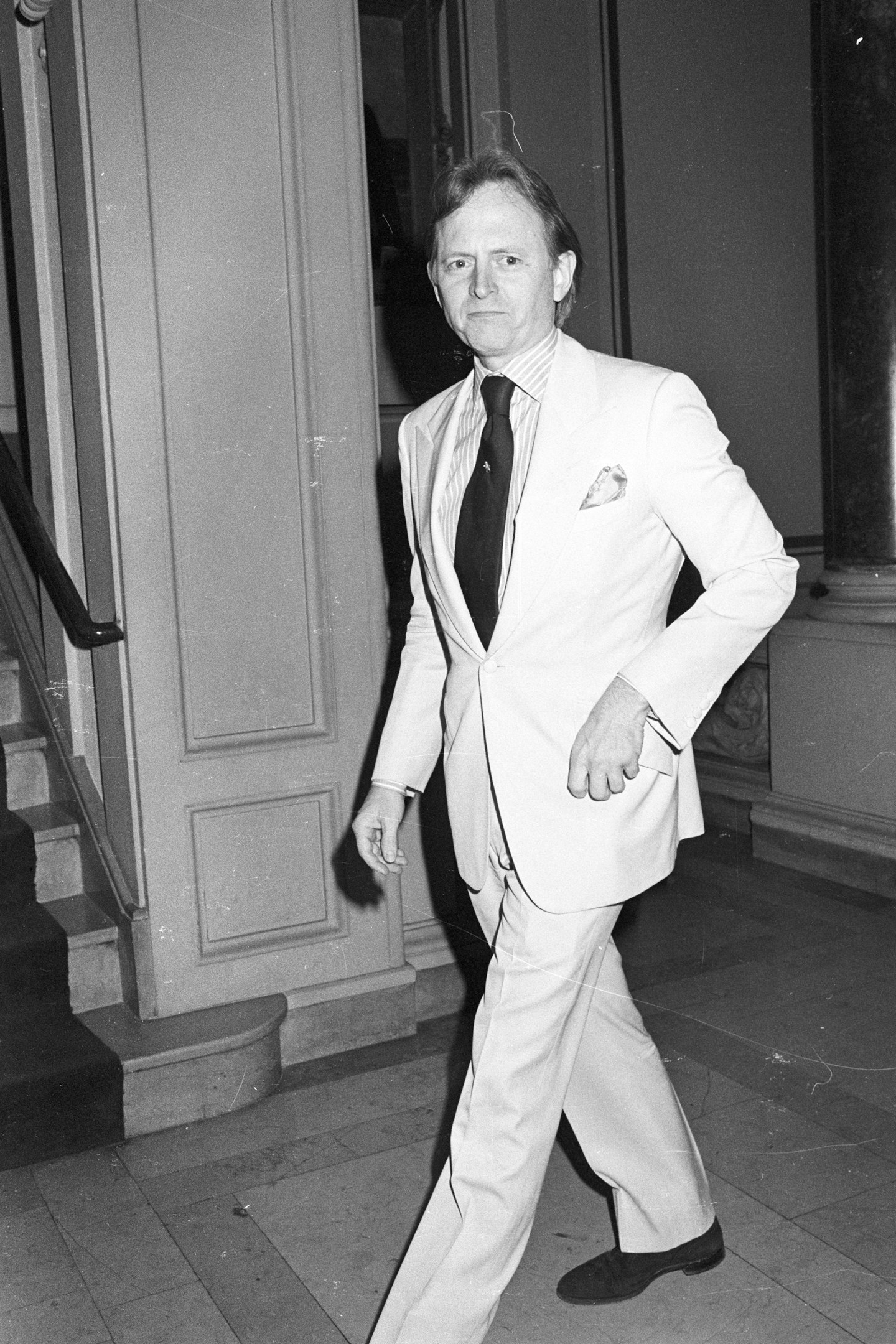

Tom Wolfe died this Monday, aged 88. And even if you've never read his work, his influence can be felt in almost every piece of journalism you'll read now. But summing up Wolfe, one of the world’s most radical, pioneering, adventurous journalists is an impossible task. He was frequently compared to Joan Didion - and the reporter, novelist and essayist's critical eye, wit and wisdom could only be matched for his taste for dandy fashion.

Tom Wolfe Writer White Suit

1 of 8

1 of 8Tom Wolfe Writer White Suit

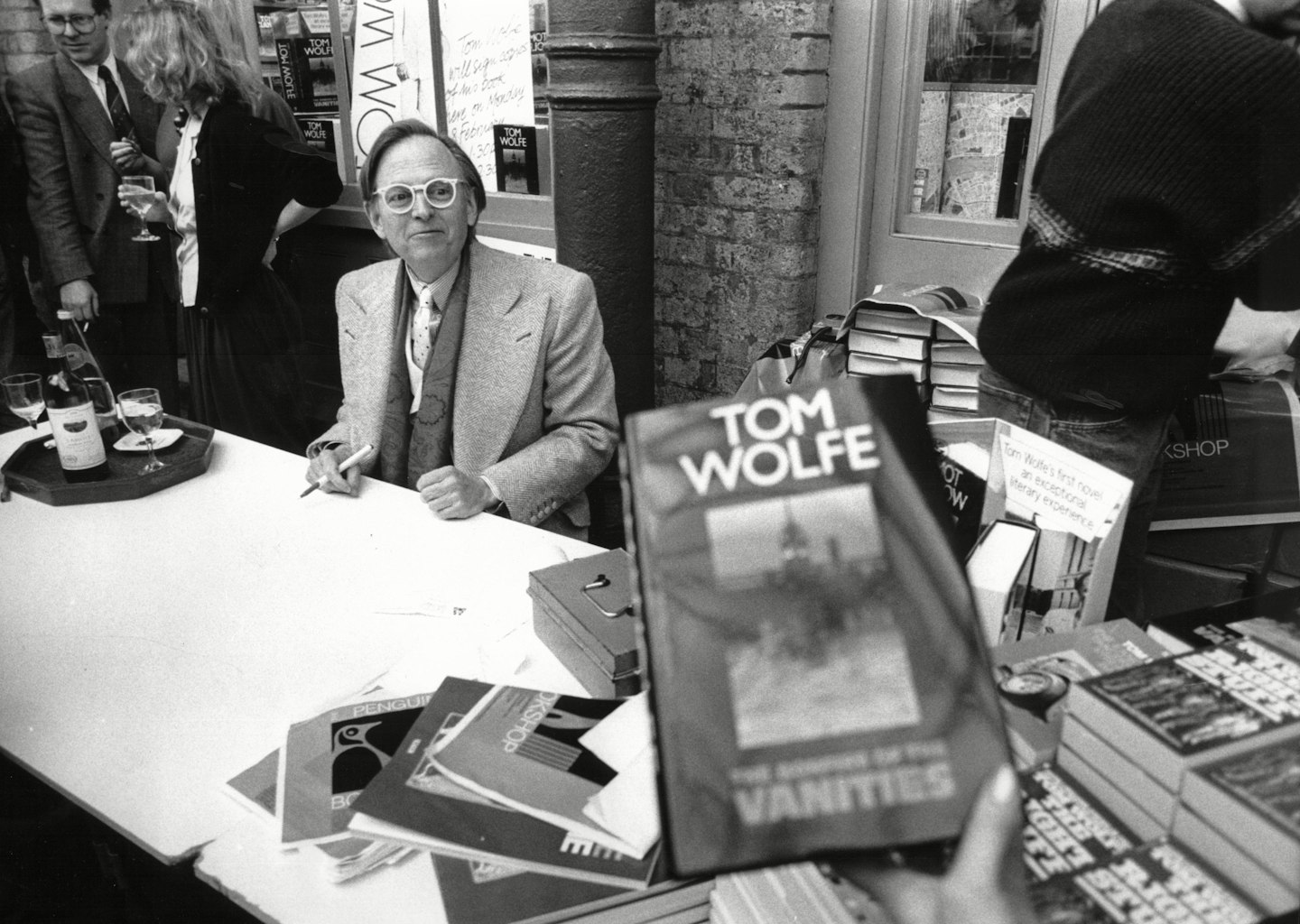

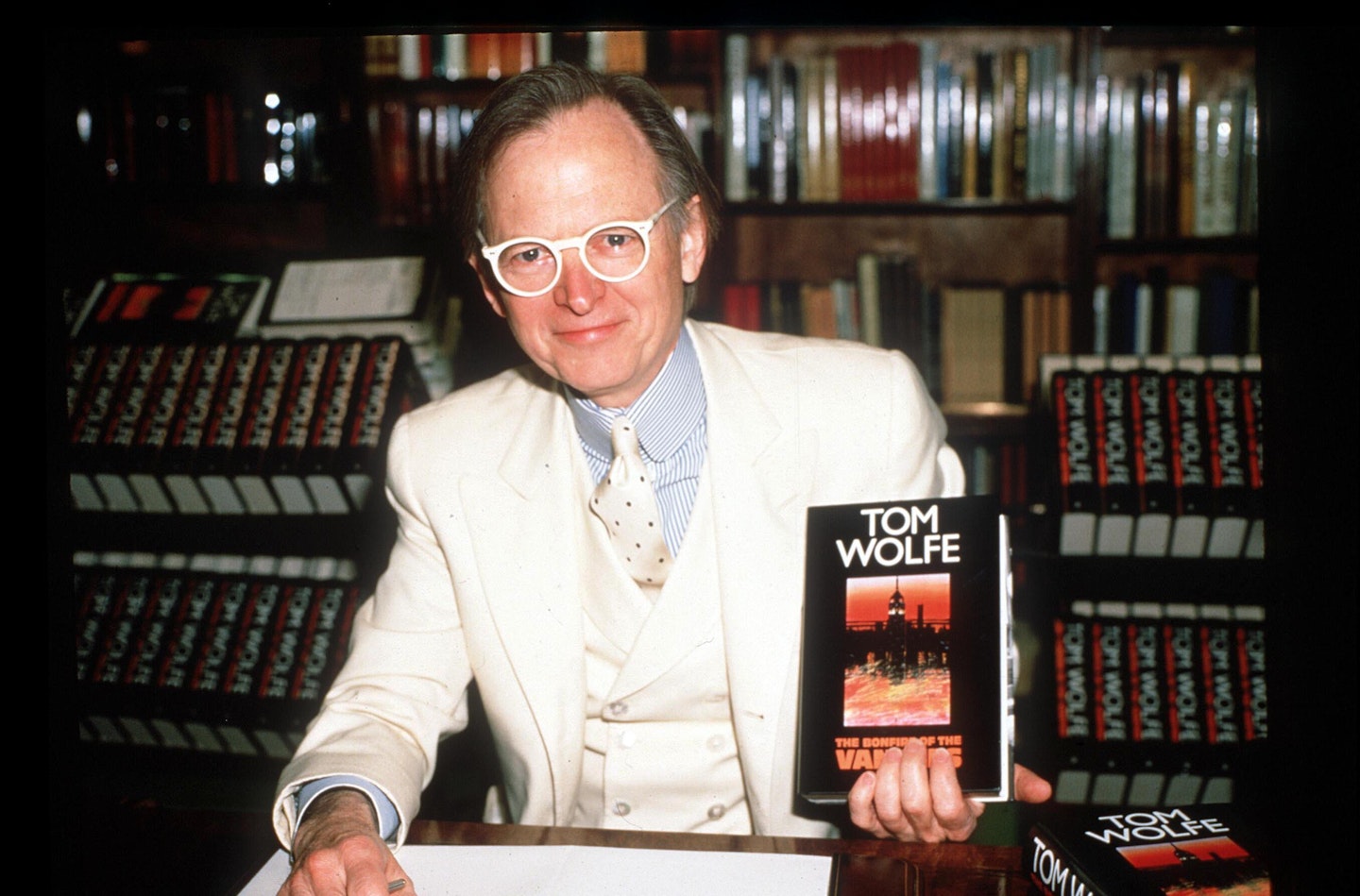

Born in 1959 in Richmond, Virginia, Wolfe may be best known for The Bonfire of the Vanities, but his lasting influence can be felt in the quipped writing of Buzzfeed and the first-person accounts that fill magazine pages.

2 of 8

2 of 8Tom Wolfe Writer White Suit

3 of 8

3 of 8Tom Wolfe Writer White Suit

He birthed his own school of writing: New Journalism. His celebrity status skyrocketed with the release of The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby a fevered, adrenaline-rush of articles written over a 15-month period for Esquire and the N_ew York Herald Tribune_ that laughed at the conventions of traditional journalism. He cracked open the industry, like a paltry walnut in the palm of his hand, with his colloquial, satirical voice and the revolutionary idea of placing himself in the story.

4 of 8

4 of 8Tom Wolfe Writer White Suit

5 of 8

5 of 8Tom Wolfe Writer White Suit

'What I try to do is re-create a scene from a triple point of view: the subject's point of view, my own, and that of the other people watching—often within a single paragraph. Incidentally, I always use the present tense', Wolfe said of his method in an interview with Vogue in 1966. He called the style, literary journalism. With The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, published in '68, he told the story of the 1960s America's perplexing mix of closeted stuffiness and wanton desire and in turn cemented his revolutionary writing style.

6 of 8

6 of 8Tom Wolfe Writer White Suit

7 of 8

7 of 8Tom Wolfe Writer White Suit

8 of 8

8 of 8Tom Wolfe Writer White Suit

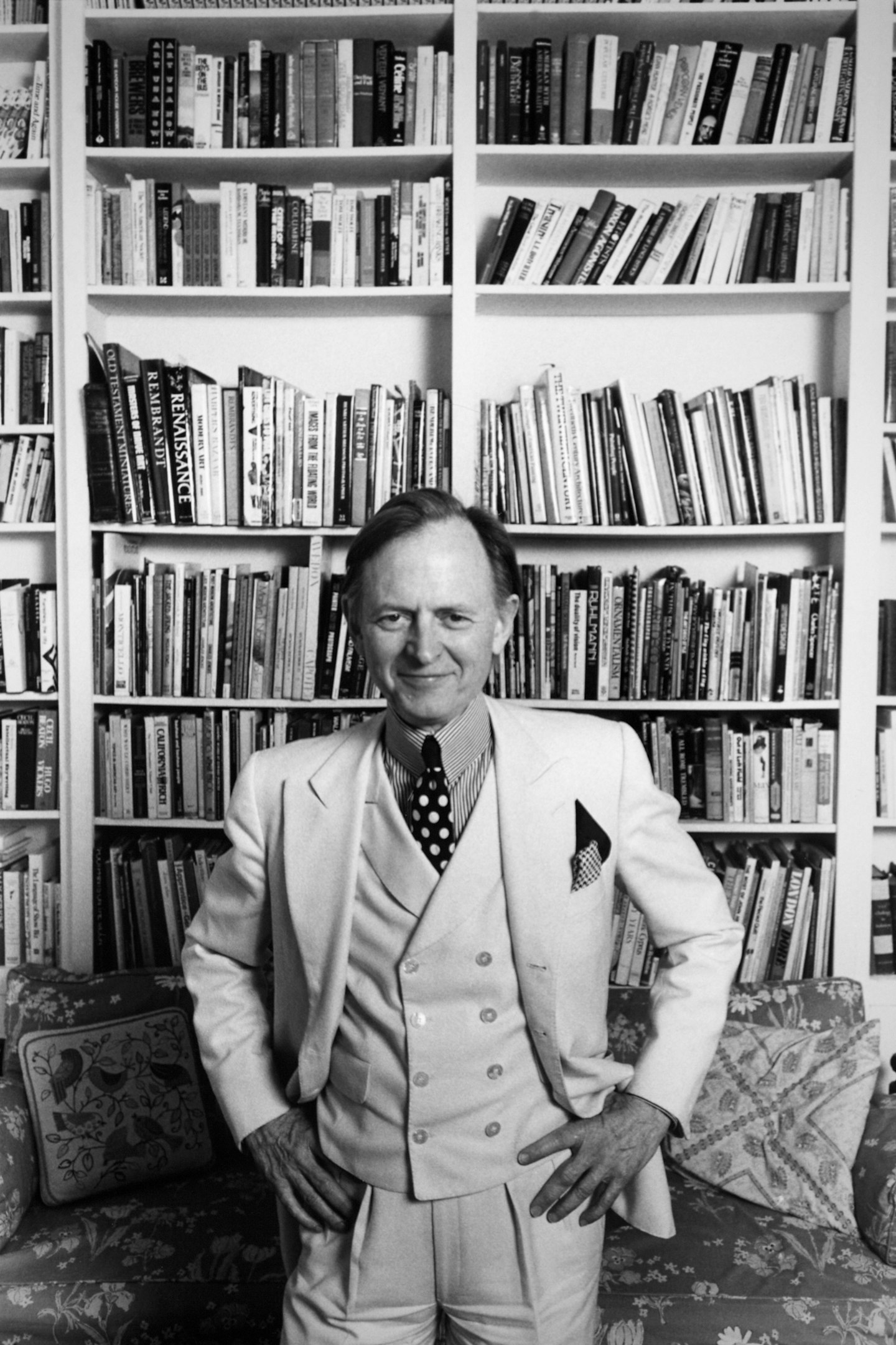

It was about this time, in 1962, when Wolfe began adopting his quintessential style. Unlike his writing, his look was archaic. He became known for his white suit (worn in winter - sacrilege), homburg hat, two-tone shoes and white tie. He told Vogue he dressed like this to 'shake 'em up' - 'em' being the viewer, his watching public. When he wasn't dressed tip-to-toe in white, he still wore a suit. With his light floppy blonde hair and unwavering uniform - only emphasized by the cane he sometimes carried - he solidified his branding.

Sure he liked to stand out, but his sartorial mindset was also strategic. He became the peacock that you could trust, ‘It was counterintuitive, but he sort of knew that if he dressed like that, his subjects would learn to trust him’, said his literary agent Lynn Nesbit to the New York Times.