It was late summer when my eyes stopped working. Staring at myself in the mirror one day, I blinked and suddenly, there she was. The funhouse version of me; doughy, dumpy and squat. I felt my hands creep down to my lower belly, muscle memory from my early twenties guiding them in movements I hadn’t made for years. They grabbed at the flesh there, pulling mercilessly. The incantation came unbidden to my mind; I embraced it.

'I need,' I thought, with violent self-loathing, 'to lose some weight'.

If you’ve followed recent shifts in women’s beauty and bodily trends, this climatic moment of extreme body dysmorphia and - to use contemporary parlance – internalised fatphobia may not come as a surprise.

As 2022 slipped into 2023, a raft of publications proclaimed balefully that “thinness” was ‘back’. Bellwethers included revived Noughties fashion trends, like the extreme low waist, garments originally modelled exclusively by the stick thin. Cultural weathervane, Kim Kardashian, boasted of dramatic weight lossand reportedly deflated some of her (allegedly) surgically enhanced assets, in order to achieve a bonier look. Speculation raged over which celebritiesmight have undergone buccal fat removal, a cosmetic surgery that sees fat pads cut out of a patient’s cheeks, with the aim of creating a more angular face shape.

And then, there was Ozempic.

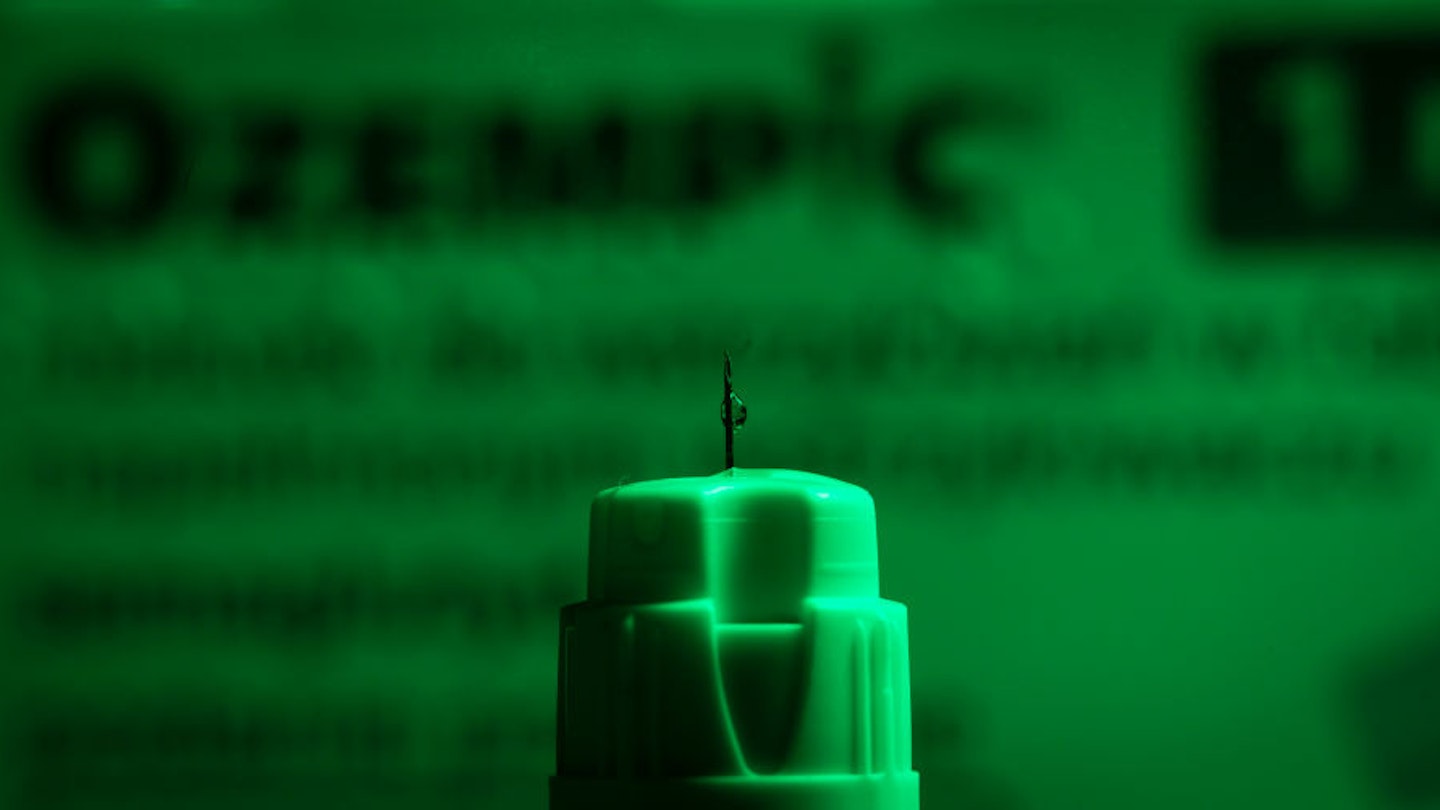

Ozempic, for the blissfully uninitiated, is the brand name slapped on the drug semaglutide, developed to treat diabetes. But that function has been overshadowed. You see, Ozempic suppresses the appetite, meaning people often lose a striking amount of weight while taking it. Skip the science (and the various pitfalls), here’s the headline: Ozempic is a weight loss drug that works, despite not yet being approved by the FDA for that purpose.

A summer of reporting on the widespread usage of Ozempic and similar medication as a favoured weight loss method among the world’s rich and famous has caused it to achieve cultural recognition in record time. As a result, the clamour for such drugs are overwhelming – widespread shortages have left diabetic patients desperate this summer. New weight loss medication, that goes further than appetite suppression and tinkers with metabolism, is being trialled, with UK Treasury backing. From pop culture to politics; the future, it seems, is thin again.

I am not here to debate the proposed use of Ozempic and accompanying diabetes medication in treating obesity - it’s not a conversation I am equipped to have, being neither obese, nor a medical professional. What I can speak to is the immediate, obvious impact that the looming spectre of a mass-market weight loss drug has already had on the imagery of famous bodies I passively digest– and my personal mental state.

Frankly, it is sending me loopy. I thought I had #healed beyond the strict, disordered eating and obsessive exercise that chequered my late teen years and early twenties. Fact check: I was wrong. Culture had just breathed out slightly for a moment.

Ozempic - or rather, what Ozempic represents – has blasted through that. Celebrities and influencers I follow have noticeably shrinking frames. They are all women. “Is she on the ozzy do you think??” I text a friend, sending her a picture of a mutual contact. Another acquaintance assures me everyone in fashion is jabbed up. The thought makes me feel as if the walls are closing in.

The 2010s, it had roundly been assumed, had ushered somewhat of a loosening of the corset strings when it came to the types of female bodies considered acceptable by a mainstream gaze. No great revolution took place; the dominant ‘coke bottle’ body ideal was far from liberating with its fetishisation of the ‘thicc’, requiring big breasts, buttocks and thighs, often paired with a cinched in waist. Certain cosmetic procedures like the BBL (Brazilian Butt Lift) became cultural shorthand, thanks to an explosion in take up. But there was more representation of bigger bodies in fashion; shops expanded size ranges on offer and there was a push for ‘body positivity’, a movement that has significantly faded in its influence since its mid-2010s heyday.

A booming fitness industry during this period tried to convince us that rhetoric favouring ‘strong’ over skinny was an indicator of changing attitudes. And perhaps it was an incremental shift. But its significance has only become apparent in the wake of the renewed ascendancy of the super skinny body as the favoured ideal among the cultural tastemakers - designers, celebrities, influencers – who set broad mainstream trends.

Mainstream is an important caveat here. Our modern age is defined by differentiation – the freedoms and options that allow us, at least in the West, to tailor every aspect of our experience to us as individuals. This has been heightened by social media, where we are having similar but crucially differentiated browsing experiences, guided by algorithms that have personally tailored the content we are seeing. There is no monoculture, not in the manner it used to exist at least. So there are pockets of the internet where fat bodies are celebrated or where the mid-size rules. In the centre, however, we are seeing skinny. Skinny, skinny, skinny.

Technically, it is easy to talk openly about weight - the town square afforded by social media ensures that. But in practice, the blowback is instant and fierce, particularly if you address uber skinny examples set by celebrities, some of whom are clearly struggling with eating disorders in broad daylight. But you’re not meant to say that. It is no longer ‘kind’ to point out the obvious. All you should be doing is worrying about yourself. The problem is, we do not exist in a vacuum; to worry about the self is to worry about the myriad pressures exerted on it by the world around us.

Individualism (and stan culture) has put us in a farcical place, where it is more of a social transgression to say, of a much-photographed person that: ‘this is not a realistic body for most women’, than it is to sycophantically applaud how ‘well’ they look, as the camera flash illuminates their clavicle through translucent skin. Is this ‘unkind’ to say? Only if you view issues with eating and weight as a moral failing of some sort. For me, the actual ethical negligence has been a collective willingness to accept and propagate thinness propaganda to such a degree that people defend the right to be ill in pursuit of size zero.

I do not want to be that thin. I don’t think I even have the capacity anymore. The sacrifice is too great a mental weight. Once you’ve managed to jettison the idea the world will end if you eat ice cream on a Tuesday, it’s very hard to will yourself back to that void. Yet I catch myself thinking back to last year, when I accidentally lost a lot of weight after giving up alcohol and walking around Europe for three weeks. Recognising that seeing my collar bones so starkly was not healthy, I endeavoured to put it on again. Now, there is a little voice in the back of my mind. “Idiot,” she says, regretfully.