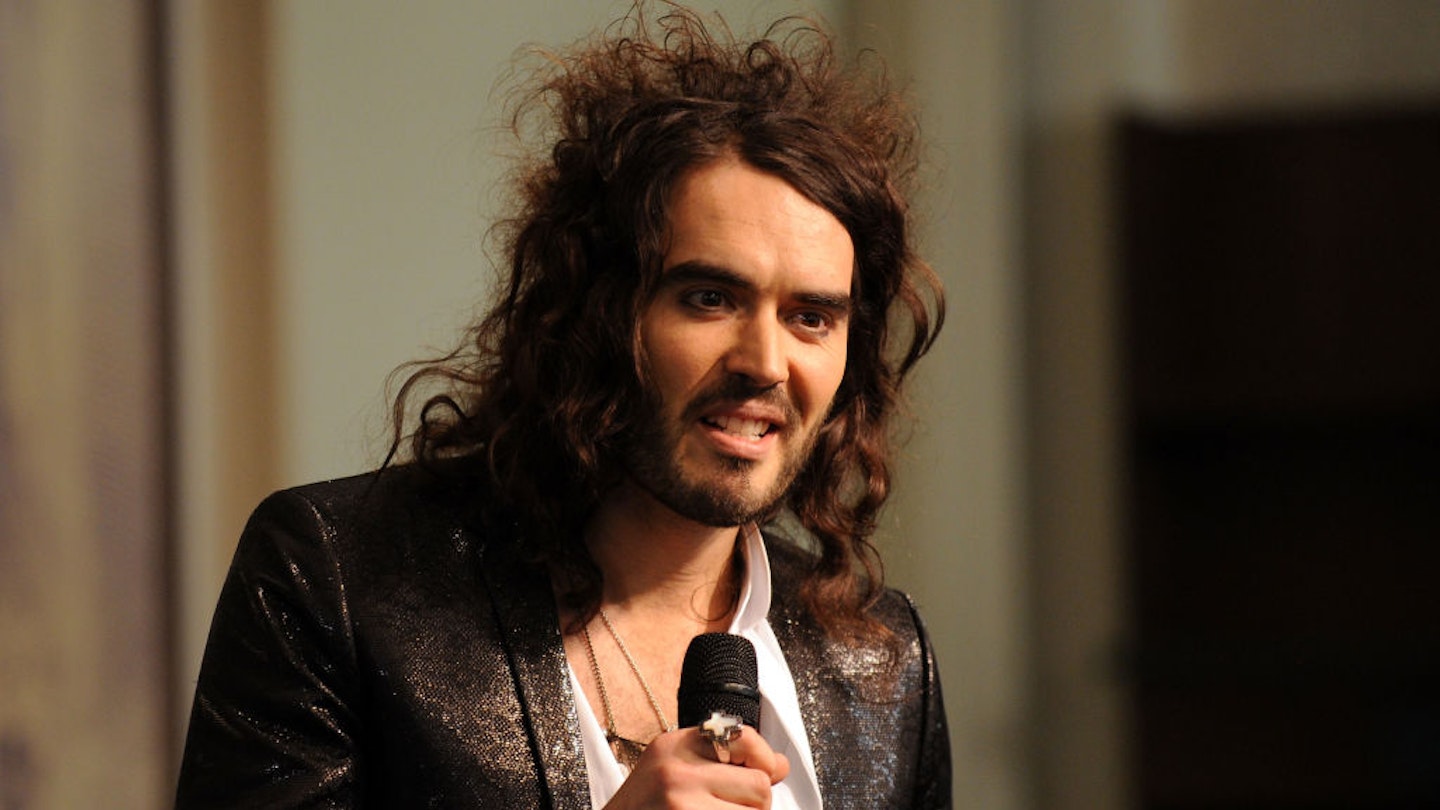

Both the press coverage and the public reaction to the recent allegations against Russell Brand has followed a depressingly familiar pattern. Gosh wasn’t it all so different in the nineties and noughties? Isn’t it scandalous that Brand was allegedly able to hide in plain sight, his behaviour an ‘open secret’? Wasn’t the toxic, sexist culture back then outrageous in the ways it rewarded and even encouraged predatory behaviour? Why are these women only coming forward now? Doesn’t it seem a bit suspicious that they’ve all spoken out at once? Doesn’t this all have a whiff of a media-coordinated pile-on about it?

Yet despite the repetition, nobody seems to notice that we react like this time and again, thus rendering the cries that this was a problem ‘of its time’ completely meaningless. ‘Things were so sexist in the 70s that you could be a sexual predator at the BBC’, they said, after Jimmy Savile’s crimes were revealed. ‘Wasn’t it outrageous that the film industry was so misogynistic that this sort of thing was normal in the 90s?’, people wondered, after Harvey Weinstein’s serial abuse came to light. And now, predictably, it is the turn of noughties culture to come under the spotlight, as we collectively shake our heads and pore over Brand’s books and television shows for proof of jokes that ‘would never be tolerated now.’

It is an understandable reaction to reach for this comfort when a high-profile man is accused of being a serial predator, enabled by the power structures around him. We want to believe that it couldn’t possibly happen now: that society has evolved, and surely somebody would do something to prevent such behaviour today. But the reality is that the same power structures, biases and normalised misogyny that enabled abusers to flourish in past decades remain alive and well today, as does the societal backlash that meets courageous survivors who dare to speak out.

Yes, noughties culture was steeped in toxic and overt misogyny: The Sun named Brand ‘shagger of the year’ four times, Page 3 and lads’ mags normalised the objectification of young women, paparazzi photographers openly tried to take upskirt photographs of teenage girls to sell to the mainstream media. But it simply isn’t true, as many have suggested, that this meant sexual violence was simply de rigueur, a fact of life in a ‘different time’. The men who abused during that period might have done so with impunity, but it wasn’t because women ‘didn’t mind’. It wasn’t because they had no idea what they were doing was wrong. It was simply because they knew they could get away with it. And they still can.

Much coverage of the recent allegations has suggested that the cultural landscape is now dramatically different. But this year a national newspaper published a male columnist’s bile about his obsessive hatred of Meghan Markle, printing his fantasies about seeing her paraded naked down the street and pelted with excrement. Just last year another paper accused one of our most senior politicians of crossing and uncrossing her legs to distract the Prime Minister in parliament. It was 2022, not 2012, when a male MP was caught watching porn in parliament, and 56 of his fellow politicians were placed under investigation for sexual misconduct.

Some people have suggested that #MeToo has made us more ready to support and believe survivors, yet the way the brave women making allegations about Brand have been treated on social media suggests otherwise. And even in the supposedly newly-sanitised mainstream media, columnists continue to tie themselves in knots trying to find ways to blame it all on the women: from an article focusing its outrage on Brand’s wife to the recent piece seeming to imply that a woman murdered by her partner had probably brought it on herself by emasculating him with her high-flying career.

In fact, if you really want to judge whether sexism and abuse have become socially unacceptable, you only have to look at the reactions of other high-profile men. Within days of the allegations against Brand emerging, famous and powerful men from Elon Musk to Alan Sugar were lining up to support him or throw doubt on the allegations. This wouldn’t happen in a society where we took sexual violence survivors seriously. Is it really a woke new world when the awful news that nearly a third of female surgeons have been sexually assaulted by a colleague is immediately met by a national newspaper printing a letter from a retired consultant suggesting that they should just ‘toughen up’ and accept it?

Yes, things have changed a little bit. Clarkson and his employer were forced to apologise for his column. Luis Rubiales eventually resigned after forcing an unwanted kiss on Jenni Hermoso after the world cup final. But if there had been a seismic feminist cultural shift, we’d have seen other men recognise that these things were wrong for themselves, not backtrack only in response to a public outcry that they first attempted to withstand. It speaks volumes that the initial response of the Spanish FA was to threaten to sue Hermoso, not to punish Rubiales. If our society had really begun to take misogyny seriously, we wouldn’t be watching Johnny Depp, who texted a friend about drowning his then-partner and ‘fuck[ing] her burnt corpse afterwards to make sure she’s dead’, signing a new $20 million deal with Dior as the face of their aptly named ‘Sauvage’ fragrance. And as for the suggestion that the women ‘should have gone to the police, not the press’, how depressing that these sneers come in the very same week we learn that an enormous 450 Met Police officers are currently being investigated over sexual and domestic violence allegations.

In the noughties, there were lads’ mags, institutional misogyny and media sexism: now we have institutional misogyny, media sexism and absolutely rampant algorithmically facilitated mass online radicalisation of young men. The misogyny isn’t less extreme, it’s simply very slightly better hidden because it’s being pumped out with targeted precision to billions of young men’s TikTok accounts and shared on enormously popular mainstream pornography websites instead of in the pages of top shelf magazines. A recent report from the Children’s Commissioner revealed that 79% of young people had seen sexually violent porn before the age of 18. Sure, lads’ mags were bad enough, but this is on a different scale.

Shaking our head over how bad things were in the past is much more comfortable than recognising that things are actually getting worse. But if we aren’t brave enough to confront the truth that institutional and cultural misogyny continue to thrive, then we continue to fail survivors. And abusers will never stop hiding ‘in plain sight’.