‘Twenty years ago, if you had an isolated individual who was becoming increasingly angry, often they would be going to their place of work and operating within a community,’ says Dr. Kaitlyn Regehr, a scholar of digital and modern culture at the University of Kent. ‘And people within that community would say something. Often, through this process of social policing, you check in with people and pull someone out of a dark place. But that was pre-internet.’

Dr. Kaitlyn Regehr has been researching online misogyny for five years and in doing so has been swept into the terrifying world of incels; an online subculture of people ‘unable to find a romantic or sexual partner despite desiring one’ whom largely (but not always) bond over their hatred of women. Often blaming women for their inability to have sexual relationships, at large incels are noted as mostly white, heterosexual men.

The term, which stands for ‘involuntary celibates’ is not a quirky description of one or two reddit forums, it is an entire ideology reportedly followed by hundreds of thousands of men around the world. And historically, it can easily translate into real-world violence.

There have been at least four mass murders, and 45 deaths, in North America alone by men involved in the incel community. In fact, Elliot Roger – whom Dr. Regehr has spent the last year researching – became a known as a hero for incels back in 2014 when he attempted to enter a sorority house with the intention to murder every woman in there, and went on to kill six people and injure 14 others.

Today, it was reported that James Davison, the Plymouth gunman who killed five people, including one very young girl, prescribed to incel ideology. And yet, police have described the incident as 'not terror related'.

According to the Center for Countering Digital Hate, 23-year-old Davison 'used online spaces to forge and share his views which include his affinity with the women hating incel movement, his transphobic views, his support for Trump, and for gun violence.'

'After he carried out the terrorist act, other members of this women-hating community flocked to his YouTube channel to leave tributes,' the Center said in a statement online. 'While this has now been closed, Facebook and Reddit pages matching his YouTube account are still active.'

In 2019, incel ideology was explored by BBC Three for their documentary ‘Inside the secret world of Incels’, which details the terrifying way online misogyny can translate into real world violence against women.

The development of the incel community – that initially began as a support group for sexually inactive people by a queer woman named Alana - is a haunting lesson in the way rampant misogyny can spread online and indoctrinate others, with Dr. Regehr noting that ‘misogyny is a massive component of the internet’.

It was a problem raised by Amnesty International in 2018, specifically in regard to social media, after they campaigned for Twitter to better protect women from online abuse, calling the social commentary platform a 'toxic place for women’.

These two issues might seem far apart, but if there is one thing Dr. Regehr has learnt about the incel community, it’s that incels are not just violent, mentally unstable psychopaths. Anyone can be drawn in if they're vulnerable enough.

‘We live in our social media age which has a whole discourse around exhibiting "perfect lives" and “perfect relationships” where people broadcast their love in very public ways,’ says Dr. Regehr. ‘And so if you are a potentially vulnerable person who is already feeling isolated and spends a lot of time on the internet seeing people you know falling in love and having fun without you, that can have a detrimental effect.

In attempting to find support groups for that detriment, lonely people can end up on the darkest corners of the internet, she says, 'taken advantage of in these forums [and] pushed down this dark rabbit hole' where an aggressive hatred of women becomes normal.

‘The internet functions as an echo chamber,’ Dr. Regehr continues. 'We all curate what we see online, on our Facebook and Twitter feeds, and it means that people who think like us and talk like us and believe in the things we do, for the most part, are echoing back our own perceptions and ideas to us.

‘If you're echo chamber happens to be a space that is promoting actual physical violence against women because you feel entitled to sex and you’re not getting it, that is just going to perpetuate and normalise those ideas so they don’t seem so outlandish to you.’

A snapshot of comments on so-called 'less inflammatory' incel forums

.jpg?auto=format&w=1440&q=80) 1 of 1

1 of 1A snapshot of comments on so-called 'less inflammatory' incel forums

This phenomenon was illustrated perfectly on BBC Three’s documentary by another man called James, whom self-identifies as an incel because he ‘never felt good enough for a relationship’. Describing his life dealing with social anxiety and paranoia, he details how his personal insecurities led to depression and steroid abuse. At first, he comes across as a lonely man whom you can’t help but feel sorry for, until he reads out a rap song he posted online about Elliot Roger.

‘Riding through the city like Elliot Roger, can’t stop me now, bitch, you ain’t no bullet dodger,’ he reads from his lyric notebook, laughing. ‘Suck on my nuts as I blow out your guts,’ he continues, before giggling the comment ‘that’s too much.’

It’s jaw-dropping to watch as the host asks him why the lyrics could be seen as problematic and how the family of the murdered women would feel hearing them, for James only then to realise how wrong it is. ‘That violence is so normalised for him that he didn't think about why that song was problematic,’ comments Dr. Regehr. ‘And he was happy to talk about it on TV.’

Case studies like James are harrowing, because they illustrate the true extent to which this isn’t just a small, dark corner of the internet plagued by murderers. Your brother could be one, your colleague in work, even your ex-boyfriend (some men have in fact had previous relationships). So what can be done about it? How do we stop this ever-growing community of angry men that can so easily become physical threats to women’s lives?

According to D. Regehr, we must start with the one thing the UK has still failed to do: actually class misogyny as a hate crime.

‘In the Alek Minassian case -which happened in April 2018 in Toronto, Canada – after he posts about [being an] incel and Elliot Roger on Facebook he then goes on a targeted killing spree,’ she explains. ‘He's now being charged with 10 counts of first-degree murder and 14 counts of attempted murder. But what I find really interesting is that he's not being charged with a hate crime, and in fact no one online who is inciting this material and language is being charged with a hate crime.’

Essentially, if misogyny were a hate crime, and incels could be charged with it, Dr. Regehr believes we could then monitor incel behaviour properly in the same way security forces monitor religious extremism.

Monitoring the online violence is just the first step though, what we must also do – according to Dr. Regehr – is also hold social media companies responsible for the way online misogyny is spread within this ‘echo chamber’ phenomenon it perpetuates. ‘There’s lots of things they can do, they can change their algorithms so you're not being fed back this content at all times,' she explains.

Then, there’s the need for education around digital literacy in order to stop vulnerable people from being sucked into the rabbit hole of inceldom. For example, courses about the impact of online engagement, and mental health support systems that can outline healthy social media use for vulnerable people whom may feel isolated from the appearance of perfection that so often exists online.

‘If those aren’t in place of course people will look for communities and support groups elsewhere,’ Dr. Regehr says. ‘And if those happen to be in the digital space and they find a dark corner which is normalising violence and allowing them to vent their anger in a really specific way, this normalisation is when it becomes more acceptable to make the jump from just making a rap video about killing women to actually doing it.’

In implementing these changes, we could prevent the spread of inceldom and in turn save countless lives. Because in this current climate, women exist with a target on their back. As Dr. Regehr notes, 'this is not violence that just sits on screens, this is violence that moves off screens and into streets.’

BBC Three’s ‘Inside The Secret World Of Incels’ is available on BBC iPlayer.

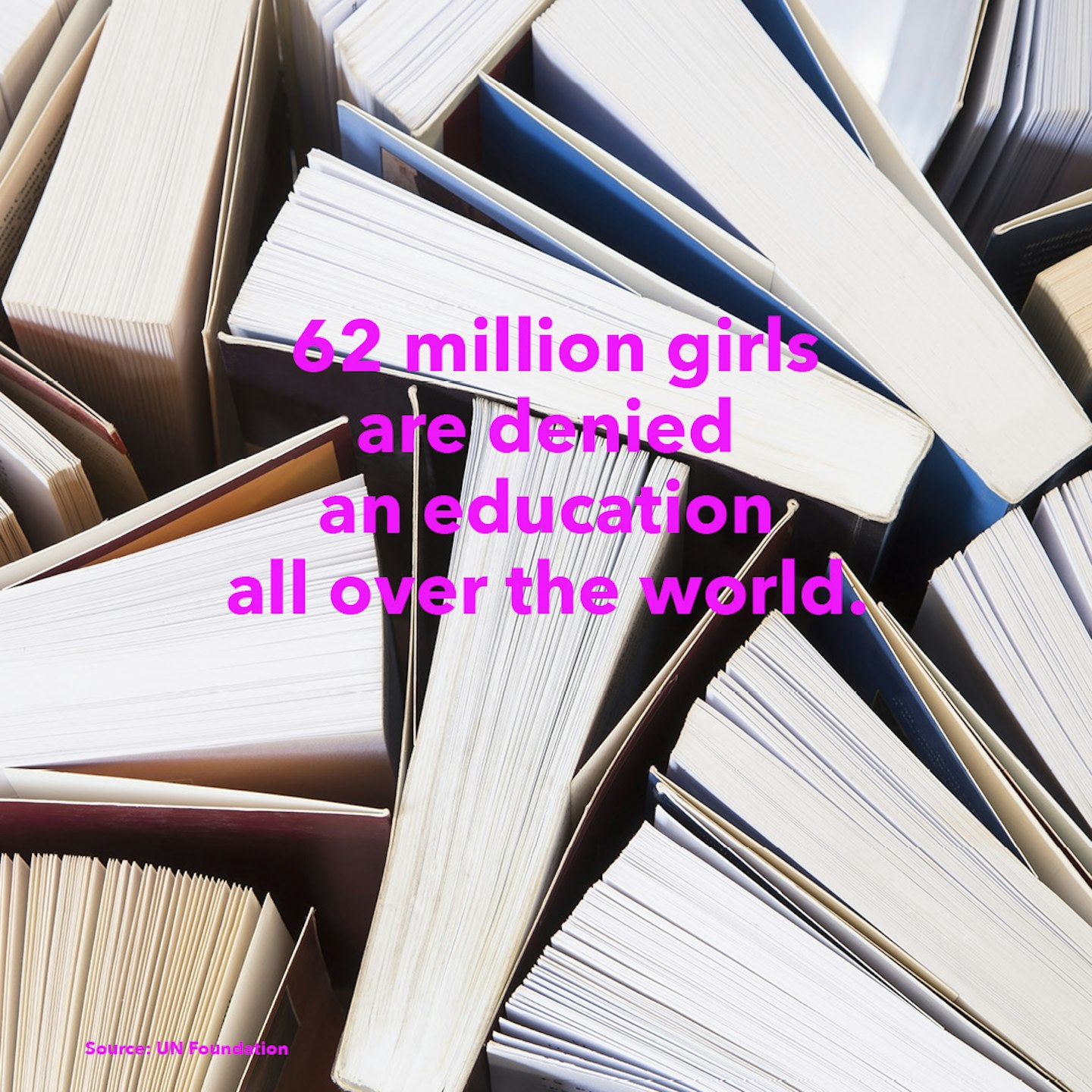

Read more: Facts about sexism around the world...

Debrief Facts about women around the world

1 of 18

1 of 18Facts about women around the world

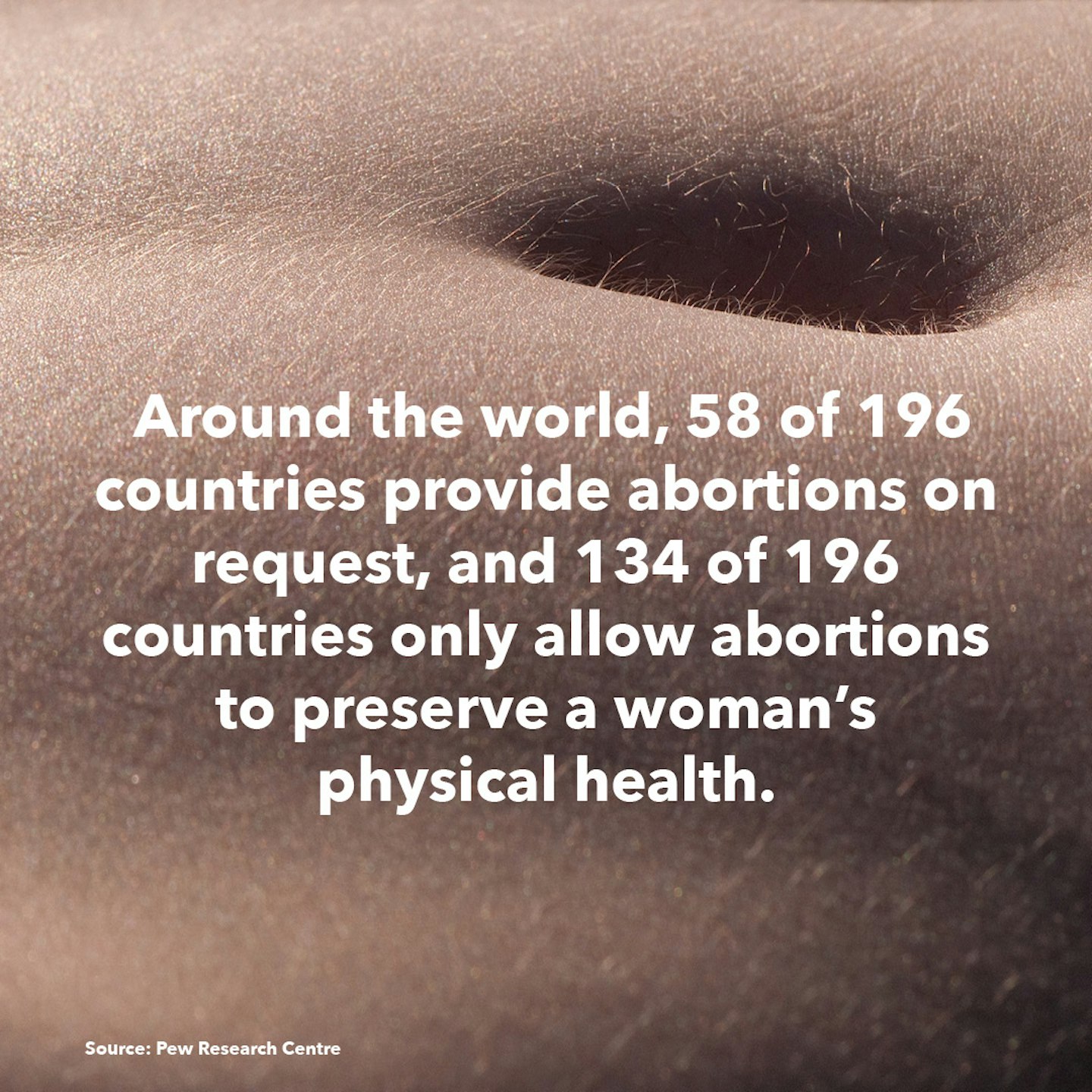

2 of 18

2 of 18Facts about women around the world

3 of 18

3 of 18Facts about women around the world

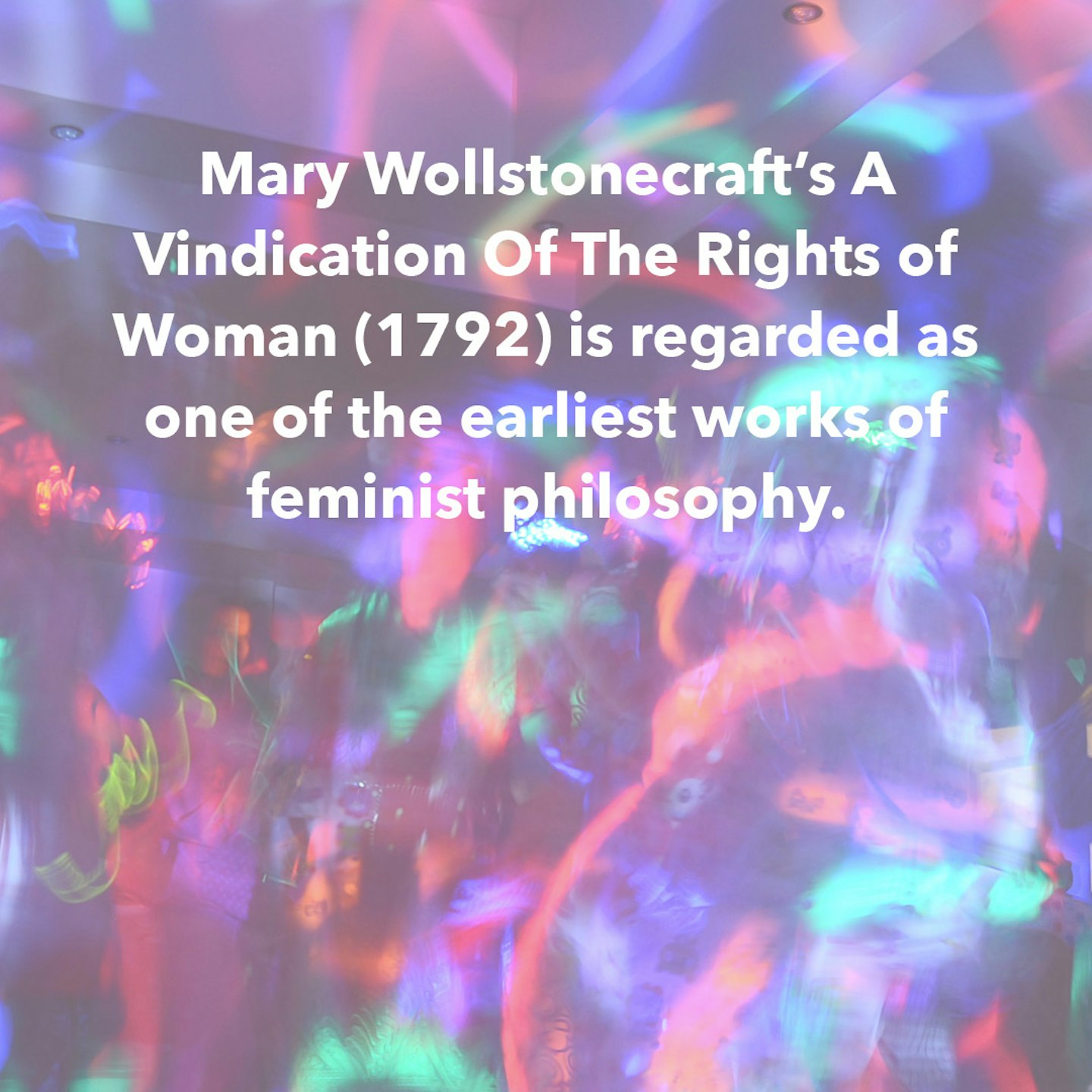

4 of 18

4 of 18Facts about women around the world

5 of 18

5 of 18Facts about women around the world

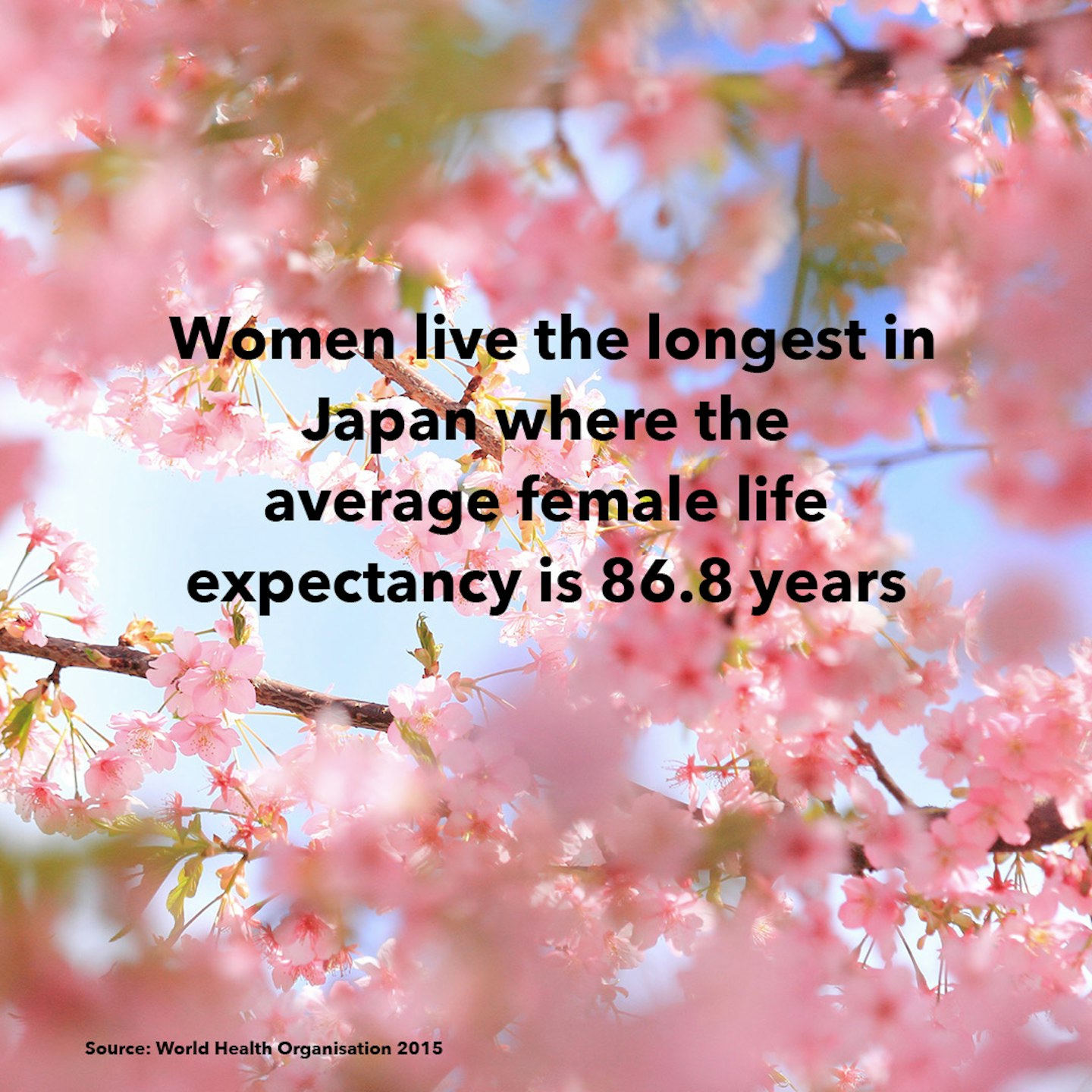

6 of 18

6 of 18Facts about women around the world

7 of 18

7 of 18Facts about women around the world

8 of 18

8 of 18Facts about women around the world

9 of 18

9 of 18Facts about women around the world

10 of 18

10 of 18Facts about women around the world

11 of 18

11 of 18Facts about women around the world

12 of 18

12 of 18Facts about women around the world

13 of 18

13 of 18Facts about women around the world

14 of 18

14 of 18Facts about women around the world

15 of 18

15 of 18Facts about women around the world

16 of 18

16 of 18Facts about women around the world

17 of 18

17 of 18Facts about women around the world

18 of 18

18 of 18