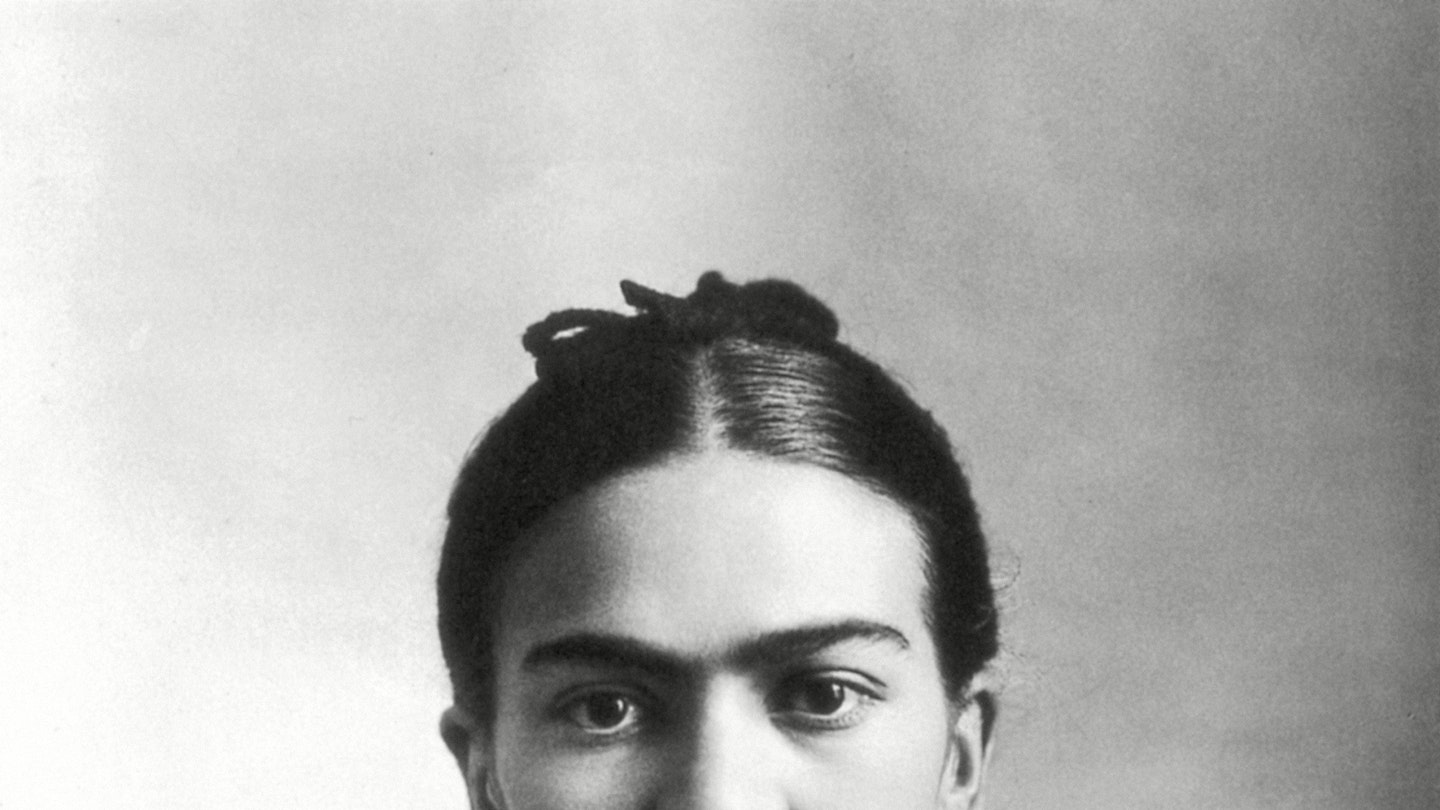

In the canon of great women artists, is there any as recognisable as Frida Kahlo? Her image was the recurring theme of her work, and has gone on to acquire iconic status, immortalised on everything from mugs to laundry bags. For many, she is a symbol as much as she is a woman. In that sense, Frida was her own greatest artwork. Opening this week at the Victoria and Albert Museum is Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, an exhibition which explores the complexities of the Mexican artist’s identity via a selection of her personal possessions – clothes, the make-up she used to enhance her monobrow and paint her lips red, jewellery and medical corsets – which were locked away for 50 years after her death in 1954, under the instruction of her husband, Diego Riviera.

It’s a nuanced portrait of a woman who continues to captivate us. ‘I felt I met her for the first time,’ says the exhibition’s co-creator Circe Henestrosa. ‘I saw an incredibly sophisticated woman, who found release and freedom through adorning herself and dressing. It’s the nearest we will ever be to her.’

What we wear semaphores messages about who we are to the world. Clothes give us permission to be the authors of our own identity. And nobody knew that more than Frida. At the centre of Making Her Self Up are Frida’s clothes, which she used to choreograph her image. The full skirts, embroidered blouses and shawls are beautiful, but underpinned by powerful personal and political statements about gender roles and national identity.

By turning to traditional Mexican dress, she was asserting pride in her national identity (Frida was ‘Mestizo’, identifing as a person of European and Native American descent). Specifically, many of the pieces come from Mexico’s Tehuana region, a matriarchal society. ‘What’s important about this dress is what is symbolises. It allows her to portray her political beliefs – she was a communist,’ says Circe. ‘I think she was just trying to look very Mexican and to find a place in a highly male-dominated environment’.

Certainly, clothes enabled her to assert her independence as a woman, without sacrificing her femininity. To dress in this way was at odds with the trends of the time. ‘Although Frida’s clothes seem ultra-feminine, actually they were a kind of liberation from what was fashionable,’ explains co-creator Claire Wilcox.

The artist as muse: Six female artists influencing fashion today…

Six female artists influencing fashion todayu2026

1 of 6

1 of 6Six female artists influencing fashion today…

1. Yayoi Kusama The highly Instagrammable Japanese artist's spots-on-steroids were splattered on everything for a Louis Vuitton capsule collection in 2012.

2 of 6

2 of 6Six female artists influencing fashion today…

2. Niki de Saint Phalle The French-American feminist artist has appeared on mood boards for Sonia Rykiel's Julie de Libran, Anna Sui, Peter Dundas (for Pucci) and Dior's Maria Grazia Chiuri.

3 of 6

3 of 6Six female artists influencing fashion today…

3. Marina Abramovic A creative collaborator of Riccardo Tisci in his Givenchy days, one wonders if we'll be seeing the Serbian performance artist in Burberry check?

4 of 6

4 of 6Six female artists influencing fashion today…

4. Rachel Feinstein American artist Feinstein is a long-time muse of Marc Jacobs, inspiring collections and appearing in campaigns. Also walked in Tom Ford's debut catwalk collection.

5 of 6

5 of 6Six female artists influencing fashion today…

5. Leonora Carrington Her work is widely referenced in pop culture, and Erdem cited the lesser known Surrealist as an inspiration for his Resort 2018 collection

6 of 6

6 of 6Six female artists influencing fashion today…

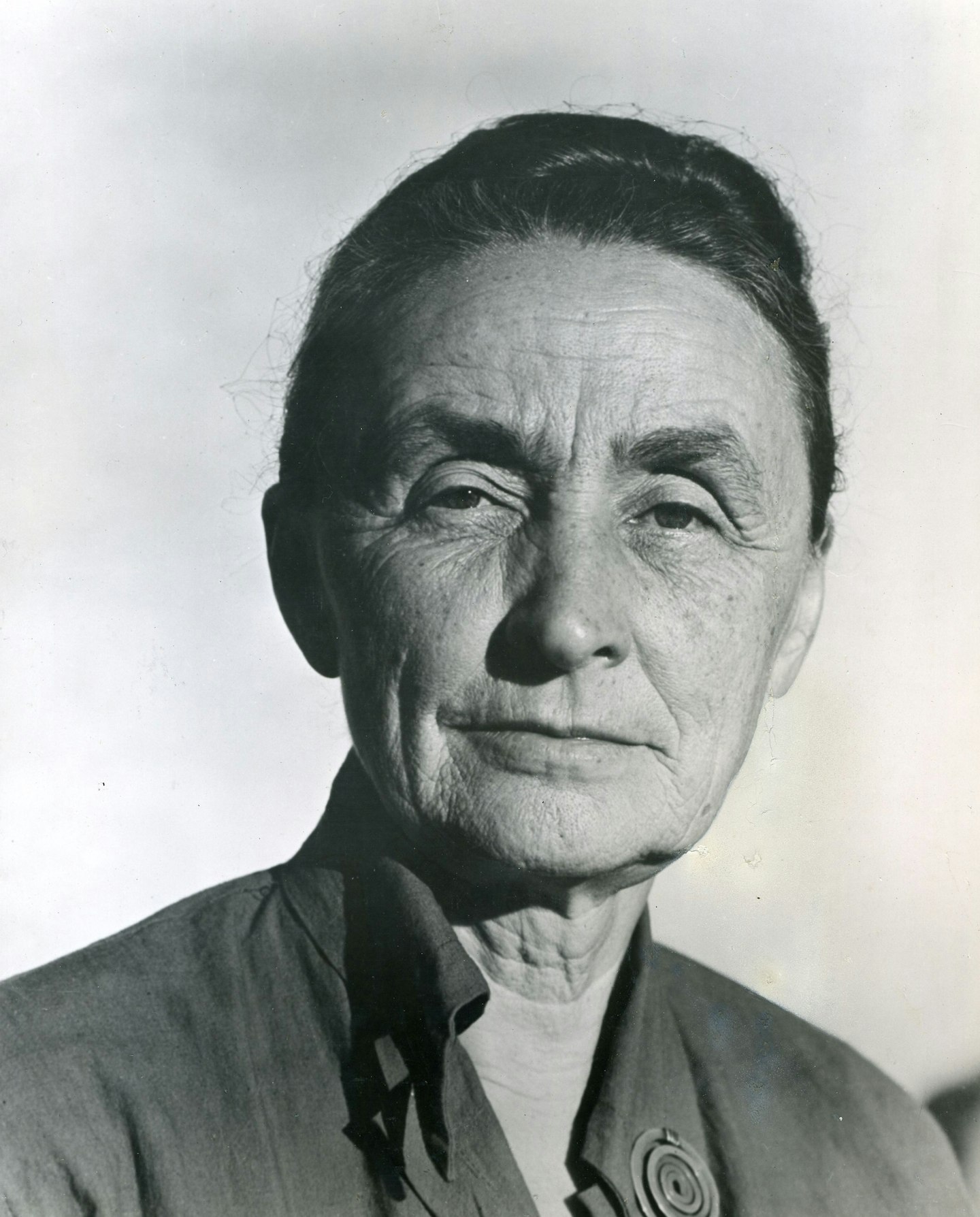

6. Georgia O'KeeffePioneered an austere, monochrome look of long skirts, tunics and wide-brimmed prairie hats. Much referenced, most recently in Dior's Cruise 2018 collection.

Clothes also gave Frida, ‘a kind of decorative carapace around a core of great suffering,’ says Wilcox. She endured great physical pain during her lifetime. At six she was struck down by polio. Aged 18, a bus crash shattered her spine, and left her bed-ridden for periods at a time. ‘The start of her career as an artist coincided with the beginning of the deterioration of her body,’ says Circe. Clothes might have been a tool to conceal the disability (the long skirts disguising her shorter, thinner right leg, for instance) but they also show her fearless refusal to shrink away. These clothes remind us that you don’t need a ‘perfect’ body to enjoy beauty, or be beautiful.

Nor does Making Her Self Up shy away from Frida’s disability; her prosthetic leg (painted, of course) is on display. ‘We’re placing it at the centre,’ says Circe. ‘She didn’t let her disability define her, she defined who she was on her own terms. And I think this is very inspiring for anyone living with any disability. I wanted to put that debate out in terms of fashion and how we look at different bodies.’ What’s refreshing is that while it is at the core of the exhibition, this doesn’t become a show about a disabled woman, but a brilliant artist who was also disabled. It couldn’t feel timelier.

Seeing Frida’s possessions up close is a poignant experience that gives you a glimpse into the essence of her as a woman – not defined by her disability, gender, ethnicity, or even just her art. She was all those things and so much more. ‘I would like people to come away with a true understanding of someone they thought they knew,’ says Claire. ‘We think she was compelling as a photographic subject. But in real life she was mesmerising.’

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up is at the V&A, 16 Jun-4 Nov, vam.ac.uk