The Covid-19 pandemic has placed us all under lockdown. Across the globe, everyone, except Dominic Cummings , has stayed home and learned to live in this anxiety inducing state where we haven’t really known what’s happening from one moment to the next. What we do know, however, is that white supremacy and racism have never taken a day off.

The idea of 'white supremacy' conjures images of neo-nazis marching with swastikas flying by torchlight or robed Ku Klux Klan lynch mobs roaming the streets of the Deep South. This rendering only works to create distance between what many would like to believe white supremacy is and not engage with how it manifests in the daily lives of black people targeted by it or the white people who perpetuate it. The Central Park Karen case involving Christian Cooper and Amy Cooper excellently illustrates the complexities of white supremacy.

White supremacy is simply the racist belief that white people are superior to people of other races. That imagined sense of superiority is so deeply ingrained, white people often lean on it with little or no provocation. That’s what Amy Cooper did when she, a white woman, called the police on a black man, Christian Cooper. On the call with 911, Amy feigned hysterics and lied that Christian was threatening her life on a video captured by the man in question.

Amy Cooper had been walking her dog in The Rambles, a section of Central Park popular with bird watchers, without a leash. Amy was asked by Christian Cooper, an avid bird watcher, to put a leash on the dog when an argument ensued. In reports, Amy and Christian disagree about exactly what happened before the video began but it’s clear that Christian was not threatening her at the time of the recording. The now viral video, first posted to social media by Christian’s sister, Melody Cooper, first shows Amy warning that she would call the police if Christian didn’t stop filming. 'I’m going to tell them there’s an African-American man threatening my life,' she says. Amy then goes on to do just that.

Amy has since lost her job and her dog claiming her 'entire life is being destroyed right now' , without, it seems, a care in the world that had she been successful in getting the police to come to her rescue, she might very well have destroyed Christian Cooper’s life.

Like many on the long, growing list of white women who call the police on black people, children included, for minor inconveniences, Amy understands the fractious relationship between the two groups. These white women, like their foremother, Carolyn Bryant Donham - whose lies resulted in the lynching of 14 year-old Emmett Till in 1955 - know the gravity of the threat inherent in white people, white women in particular, calling the police on black on black people. It is a threat of death.

A white woman so appalled at the mere notion of a black man telling her what to do so calls the police on him sadly is a tale as old as time. It’s the first chapter in the racist handbook, the white supremacist manual if you will. What is a little more challenging for well-meaning white people, and some people of colour, to understand is the white supremacy implicit in their portrait of Christian Cooper.

'This is Christian Cooper,' reads Joshua Potash’s tweet accompanied by a video of Christian Cooper beaming as he speaks of the joys of bird watching. Cooper is as a clean cut, bald headed black man. He has a stocky build, maybe he works out, but he wears wire rimmed glasses and his gesticulations speak to the kind of passions you can only experience when you truly enjoy something. Potash goes on in his thread to explain '…I share this more b/c we see the narrative “she called the police on a black man” like the man is some faceless, nameless idea rather than a living breathing person.'

It might have been Potash’s intention to assert it wouldn’t have mattered if Christian had '7 tattoos on his face', Amy shouldn’t have behaved the way she did (as he tweeted). But what he actually does is create a distinction between the kind of black man Christian Cooper is and the kind of black man it might have been permissible for Amy Cooper to call the police on.

Christian Cooper is a 'good black man', mild-mannered and thoughtful about nature. He speaks in a way white people can readily understand and easily relate to, he doesn’t have visible tattoos and appears nonthreatening. This presentation of Cooper tells white people, white women specifically, that Cooper is the archetype of trustworthy, acceptable blackness, in whom no danger can be found. Being 'good' is a falsehood of respectability politics that black people and other people of colour often internalise in the hopes that making white people comfortable will immunise them from discrimination and police brutality. It does not.

This is not hyperbole. We know this because even now during this pandemic, our social media feeds are awash with the hashtags of the names of black people killed by police and civilian white people acting as law enforcement. Ahmaud Arbery was killed by Gregory and Travis McMicheals while jogging in February. The McMicheals claimed they suspected he was a thief who they were apprehending. Only after a video of the moment Arbery lost his life went viral, 74 days after his killing, were they arrested and charged with his murder. The FBI are now investigating the case as a suspected hate crime amid mounting speculations of a coverup to protect the McMicheals. Their attempt to posit Arbery as a criminal exists to justify the McMicheals’ taking his life. If Arbery were a 'good', obedient black man and allowed himself to be detained by these white men, he might still be alive.

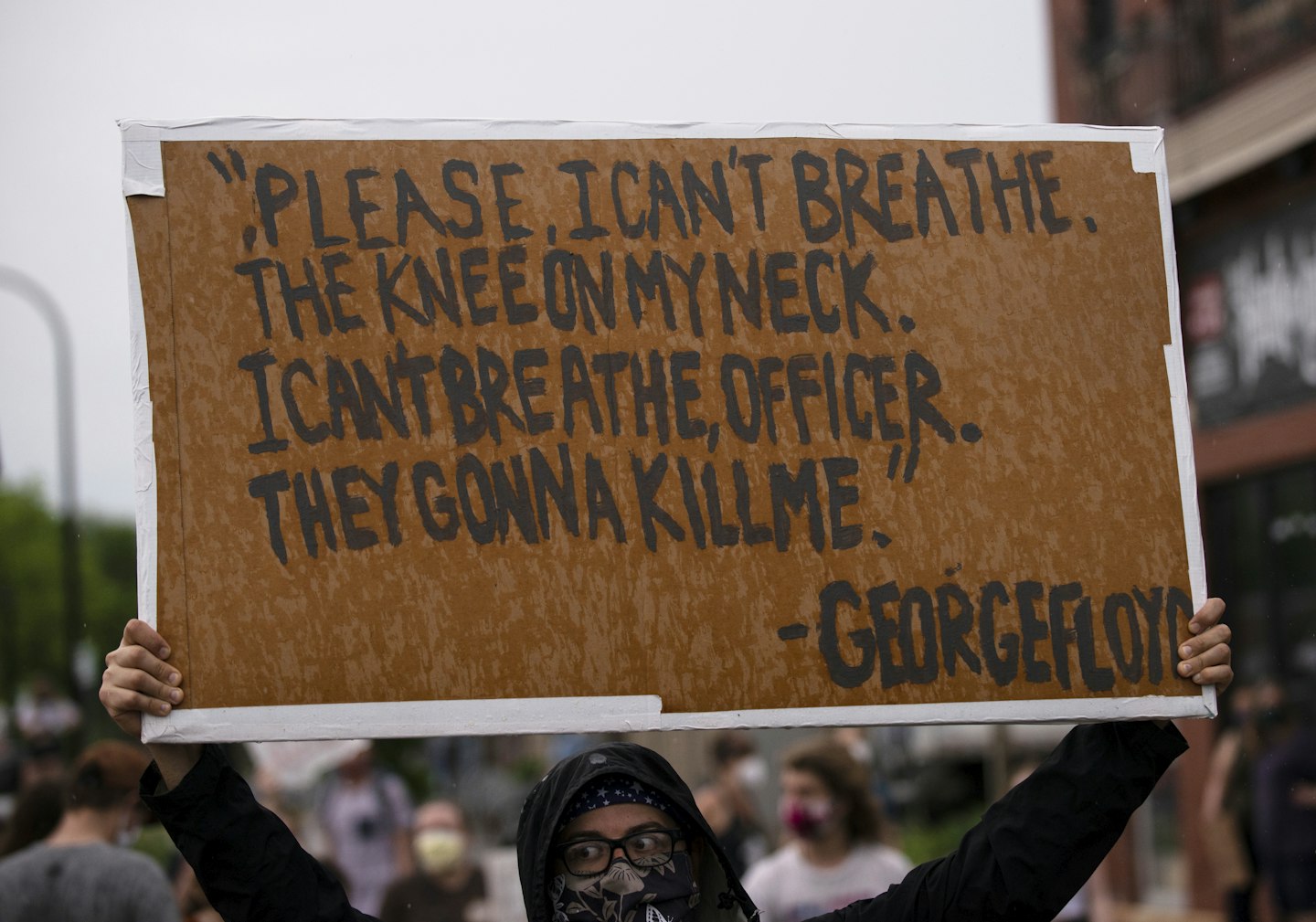

George Floyd was killed after police detained him by kneeling on neck this week in Minneapolis. Police were called by a grocery store who claimed Floyd had forged a cheque. According to initial police reports, Floyd resisted arrest. However, newly released video shows George Floyd being forcibly removed from his vehicle apparently conflicting with the police department’s account of what took place. Portraying Floyd as a 'bad' black man who resisted arrest helps to justify why he was killed. Had George Floyd simply cooperated with the police, he would still be alive. Respectability politics puts the responsibility for their killings on the victims.

As a British onlooker, it is easy to dismiss these cases as exclusive to America and ignore the way this same white supremacy threatens black people right here in Britain. But we have had our own problematic cases. Campaigners are currently asking the government to review police use of tasers and plans to arm 10,000 officers following some incidents.

In order to eradicate white supremacy it is vital that we, as a global society, understand how it presents itself and how we as individuals consciously or unconsciously perpetuate its ills. Caricatures of 'good' and 'bad' black people only work uphold white supremacist ideals about respectability and create wriggle room for racists who wilfully target black people to excuse their violence. In order to have full accountability we must resist the urge to fall into the trap of seeing one kind of black life as more valuable, more deserving of life than another. Being a 'good' black person will not ensure survival from white supremacy and it’s time we all stop perpetuating this fallacy.

.jpg?ar=16%3A9&fit=crop&crop=top&auto=format&w=1440&q=80)