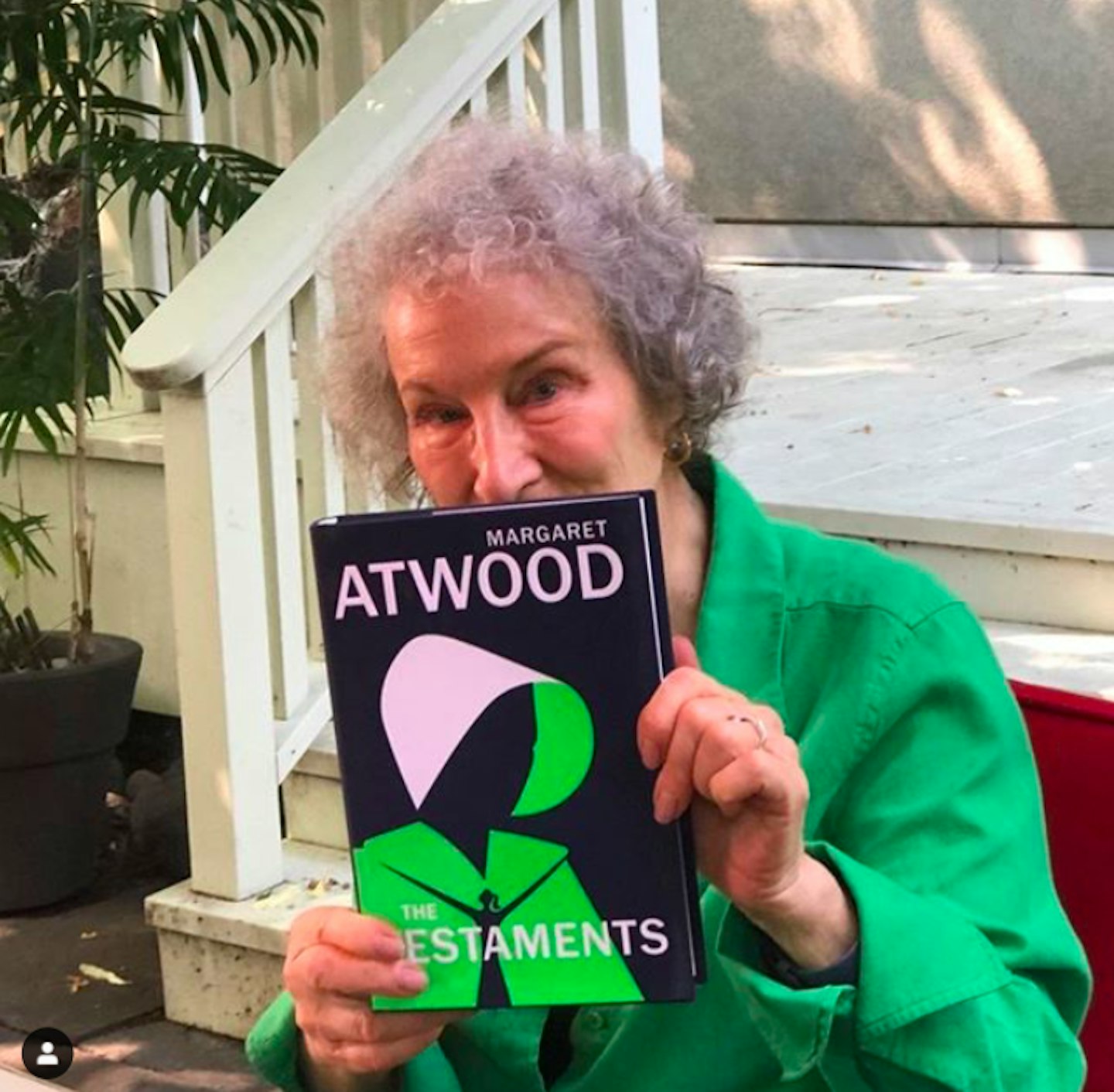

Fans of Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale have been waiting for its sequel for a long time – more than 30 years, in fact. This week, the world held its breath (and then sharply exhaled) as one organisation after another broke the strict embargo on the follow-up novel, The Testaments.

Slated for release on 10 September, happy (and surprised) Amazon shoppers posted pictures of their shiny new copies, shipped a week before they were supposed to be, to social media. Independent bookshops are, understandably, pretty furious. (Watch this space to see whether there are any ramifications for the internet giant breaking a contract which would have seen smaller stores heavily punished, and will do a lot of damage to that release-day rush. Then again, don’t hope too high.)

Life for children in Gilead is described as variously cosseted and restrictive – and certainly suffused with the misogynist moral code fans will recognise

ANYWAY. Publisher Penguin Random House has attributed the slip to ‘a retailer error which has now been rectified’ – but, rectified or not, the cat’s out of the bag. Already shortlisted for the Booker Prize, reviews of The Testaments are flooding in (and they’re overwhelmingly positive). Better early than never, eh! So, what do we know?

The Testaments is set in the same universe as The Handmaid’s Tale, around 15 years after we leave Offred in Gilead, and it’s narrated by three different women. Lydia, one of the Aunts entrusted with indoctrinating Handmaids and Wives, is introduced as a founding force of Gilead’s strict ‘space for women’. She writes secretly, conflicted as she upholds the world which constrains her: ‘The corrupt and blood-smeared fingerprints of the past must be wiped away to create a clean space for the morally pure generation that is surely about to arrive. Such is the theory.’

Then, two girls – Daisy is a new recruit, fresh to Gilead from Canada: 'I thought I knew what was wrong with people then […] especially adult people. I thought I could set them straight.' Adopted Agnes, meanwhile, wields her testimony to shed light on questions about its culture, schooling, stories.

Life for children in Gilead is described as variously cosseted and restrictive – and certainly suffused with the misogynist moral code fans will recognise. Agnes’s testament explains how, ‘The man eyes that were always roaming here and there like the eyes of tigers, those searchlight eyes, needed to be shielded from the alluring and indeed blinding power of us – of our shapely or skinny or fat legs, of our graceful or knobbly or sausage arms, of our peachy or blotchy skins, of our entwining curls of shining hair or our coarse unruly pelts or our straw-like wispy braids, it did not matter’.

In a world which arguably resembles Atwood’s dystopia more rather than less as time goes by, when the US Vice President signs bills requiring fetal remains to be buried or cremated and access to birth control and Planned Parenthood are being stripped at a rate of knots, appetite for Atwood’s lens on a not-so-distant future has rocketed. As for The Testaments, it would be kindest to hold off until 10 September to get it from your local independent bookstore… If you can’t bear the wait, you’ll find no shortage of similar material right beneath your nose, or out the window.