Before the technician in Dr William Van Gordon’s laboratory attaches the Finometer to my finger (to measure my blood pressure) and places a monitor near my heart, I’m nervous. I’m at the University of Derby to talk to him about his ground-breaking research in the field of social media addiction and I’m worried that his machine will confirm that I am a mindless, addicted narcissist.

Recently, I’ve caught myself becoming irritated with friends as they talk, itching to pick up my phone to check Instagram. I even once deleted the app, only to find myself subconsciously unlocking my phone as if to open it again. I’m concerned about the role tech plays in my life and in our global society, but the very mention of a digital detox makes my eyes roll back into my skull. Plus, like many people, I can’t do my work without a smartphone.

So William’s research got my attention. He recently discovered a new social media- related ‘ontological addiction’, which means being addicted to yourself, and I think it could help me – and you – understand why we’re so drawn to social media.

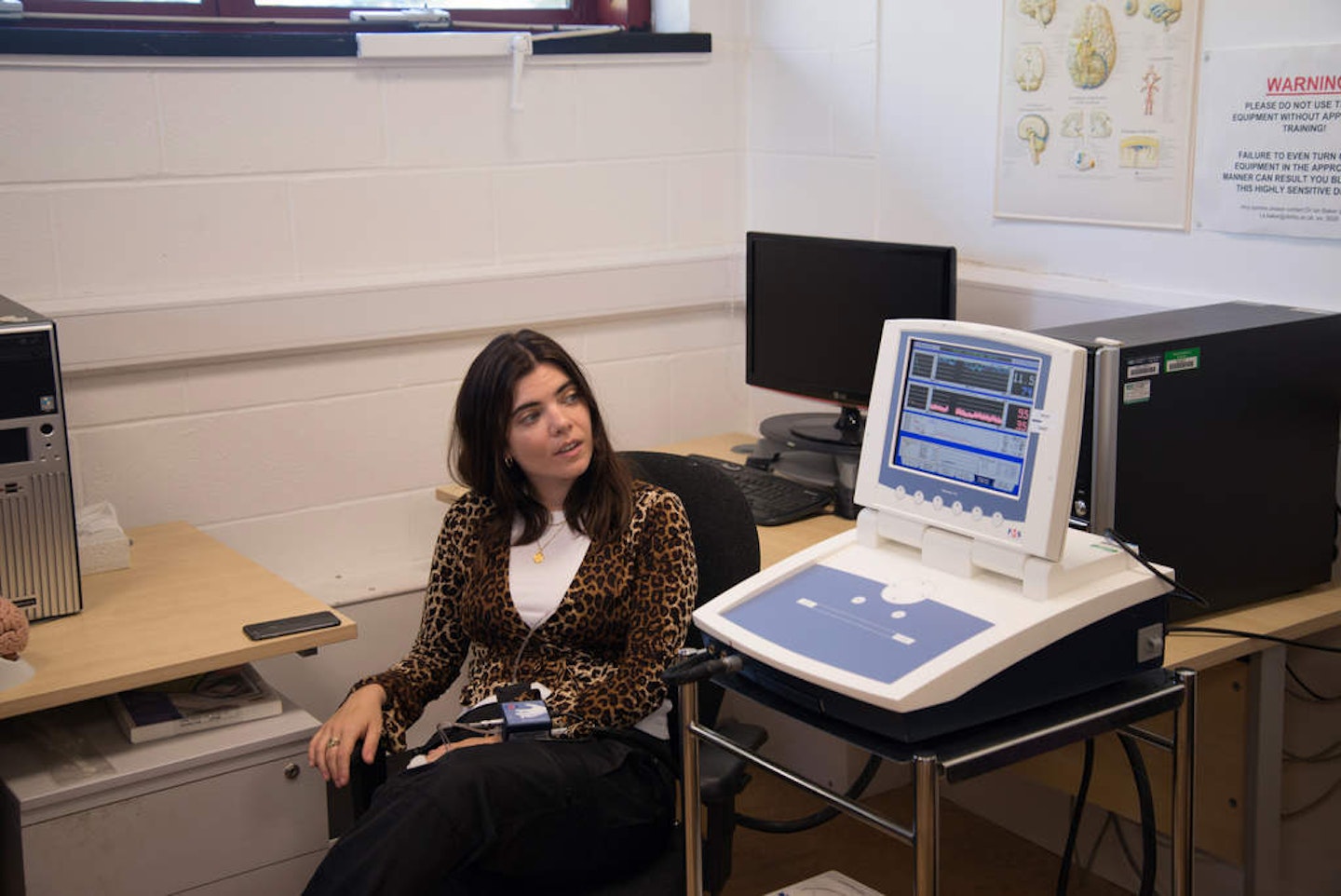

Once I’m wired up, William asks me to take a selfie and post it on Instagram. I sit strapped to the devices and wait. The screen looks like a ’90s computer game, and I feel like I’m in a scene from Netflix’s Maniac.

It’s not long before the white line that measures my blood pressure starts to peak. ‘Your blood pressure increases whenever you engage with social media,’ William notices, ‘especially when you anticipate receiving positive or negative feedback.’

I’m not surprised. It alarms me, but I regularly ignore the rush I get when I post. Seeing it here, in black and white, I can’t ignore its impact. The screen shows the anatomy of my Instagram post. My heart races, my blood pressure spikes and my brain fizzes because, as William explains, these physiological reactions ‘mirror psychological and neurological changes’ that are harder to measure but definitely happening inside my head. Social media, he says, is deliberately set up as a system of potential rewards: likes, comments and shares. The problem is, ‘the brain remembers these rewarding experiences and seeks them out again and again because of dopamine – a neurotransmitter that facilitates feelings of pleasure.’

This phenomenon – ‘dopamine-driven feedback loops’ – made headlines last year when Chamath Palihapitiya, an ex-Facebook exec, spoke out about feeling guilty for developing a platform to feed them.

But is all of this doing any lasting damage? William says there’s currently insufficient research to link lasting changes in the brain structure. ‘However, the brain is hardwired to remember types of behaviour that lead to reward. While, for most people, the neuropsychological effects of engaging with social media are likely to be short-lived, it is feasible that those who consistently take social media usage to an extreme over a prolonged period could experience lasting effects on the brain.’

Through his research, William wanted to go further than confirming what we all already know – that social media is addictive. He wanted to find out why. Until now, he explains, ‘Science only recognised two forms of addiction: chemical, such as drugs and alcohol, and behavioural, such as gambling or computer games.’ By studying people’s interactions with social media, he uncovered this new, third type of addiction: ontological, or being addicted to your own existence. He says it could explain what it is about social media specifically that lures so many of us in.

‘Likes,’ he says, ‘are a carefully designed reward that reaffirm a person’s sense of self.’ They are addictive because they ‘encourage us to keep engaging with social media to get more confirmation of our existence’. Apparently, the pleasure and rewarding feelings I talk about when the likes start rolling in on my selfie are ‘typical’ of ontological addiction. This makes me feel both better and worse.

I confide in William that, while I’m trying to wean myself off Instagram, during the hour that we’ve been talking, my arm has itched to reach for my phone more than once, despite the fact that I’m really enjoying our interview.

‘It makes sense,’ he says. ‘I’ve seen people display withdrawal symptoms when they try to come off social media.’ The problem, he explains, is that, ‘Online, people can construct another layer of identity that feeds solely on likes, shares and followers in order to exist. That is not necessarily an accurate portrayal of their true nature but it becomes consuming.’ This is how social media can take us further away from who we really are; instead, it focuses us on who we think we are, or wish we were.

It’s difficult to say exactly how many people are affected, but we do know that the average Briton checks their phone every 12 minutes, and that young women are more likely to be addicted to social media than young men.

William says ontological addiction is cause for concern because, ‘It has serious implications for our mental health, relationships with others and relationships with ourselves.’ The more drawn we are to engaging with our online selves, the less engaged we are in our real-life relationships.

I ask how he would compare this to other addictions, such as smoking or gambling. ‘Put it this way,’ he says. ‘I think that in our lifetime we will see public health warnings about social media in the same way we see them on cigarette packets.’ This is hardly far-fetched. The Government is already drawing up guidelines around young children’s use of social media, including time limits.

At its most serious, William says, being addicted to yourself ‘blurs your understanding of reality’. I think that’s what I’ve started to pick up on whenever I post. I know the validation isn’t real and yet my ego craves it like a bottomless well that I can never fill. I can see how easy it would be to gameify your life, designing your existence for the Gram by doing things you know will get likes and gain you followers over what actually makes you feel good.

On social media, we see everything as an individual because our online self is, literally, the centre of everything, since we access the world via our profile. And, ‘the more we live out our lives through this lens of “me, mine and I”, the more we strengthen our ego and draw ourselves away from the present moment,’ says William.

He doesn’t pretend to have a definitive answer but, he says, a good place to start is an awareness that you could be addicted to your online life. ‘Then you can try to create a new sense of self – one less egocentric that understands that you are not an individual but a vital component of a larger society.’

The Greek hunter Narcissus saw his reflection in a pool of water, fell in love with it and drowned. Perhaps, like him, we are drowning. But, I’m wary of judging anyone who, like me, is in thrall to the online version of themselves.

If, as individuals and as a society, we don’t like the reflection of ourselves we see online – a constant stream of selfies – it’s up to us to change it. Our ontological addiction is telling us something crucial about who we are – and we should listen.

Are you addicted to social media? Let us know at feedback@graziamagazine.co.uk