Christmas, when I was small, meant a chocolate advent calendar, and a tinsel tree, and a pair of my mum’s tights in place of a stocking, the feet heavy with tangerines. It meant my mum driving us down the M4 to spend the season with my grandparents. It meant placing the fairy on the top of their larger plastic tree – my grandparents always left the uppermost branch bare until I arrived - and stirring the Boxing Day trifle with Grandma, and watching The Snowman while sitting on my grandpa’s knee.

For my mum, I know now, this all added up to something rather different: less cosy, far more complicated. These were her in-laws – my mum’s father was dead, and her mother was in a nursing home with advanced Alzheimer’s. Mum and Dad were separated, eventually to divorce. The separation, and the situation that had brought it about, had been painful for all concerned, as such things usually are.

Mum got on well with her in-laws, but it can’t have been easy for her to spend Christmas with the family of her estranged husband – not least when my dad quite often turned up, too. One year, as I recall, he brought his girlfriend with him. I can hardly imagine now how awkward that Christmas must have been for everyone – my mum especially – while I, oblivious, ran around in an excited childish daze.

I mention all this because it seems clear to me now, at a distance of three decades, that this early experience of Christmas – of messiness rather than perfection; of fractured relationships, and everyone making the best of things, despite the strangeness and trickiness of it all – framed my adult understanding of what Christmas means.

I adore it especially, I think now, because it is messy and imperfect; because really, so is life

I adore Christmas. However little money we had, however difficult our circumstances, Mum always made it special. And I adore it especially, I think now, because it is messy and imperfect; because really, so is life, and it’s only in learning to accept this that we can stop berating ourselves for our mistakes, our flaws, our failures.

Relationships can be strange and tricky throughout the year, so why wouldn’t they remain so during a couple of highly charged, alcohol and sugar-fuelled days in December? TV adverts sell us perfection – attractive, expensively dressed, uniformly cordial relatives and friends raising their glasses over glistening bronzed turkeys – but we all know that it’s an illusion, a mirage. Nobody’s Christmas is really like that – or if it is, lucky you, and please can I join you next year?

Most of us, at some point, will argue with each other, or find ourselves alone, or unwell, or grieving, or hard up, or just struggling in any of the innumerable ways we all struggle on every other day of the year. And that’s OK. That, in my view, is what Christmas really is: a celebration of the messiness of life, as much as of its glories and wonders; of kindness, and generosity, and the ways we all find to be there for each other when life gets difficult, as it inevitably does.

TV adverts sell us perfection – attractive, expensively dressed, uniformly cordial relatives and friends raising their glasses over glistening bronzed turkeys – but we all know that it’s an illusion

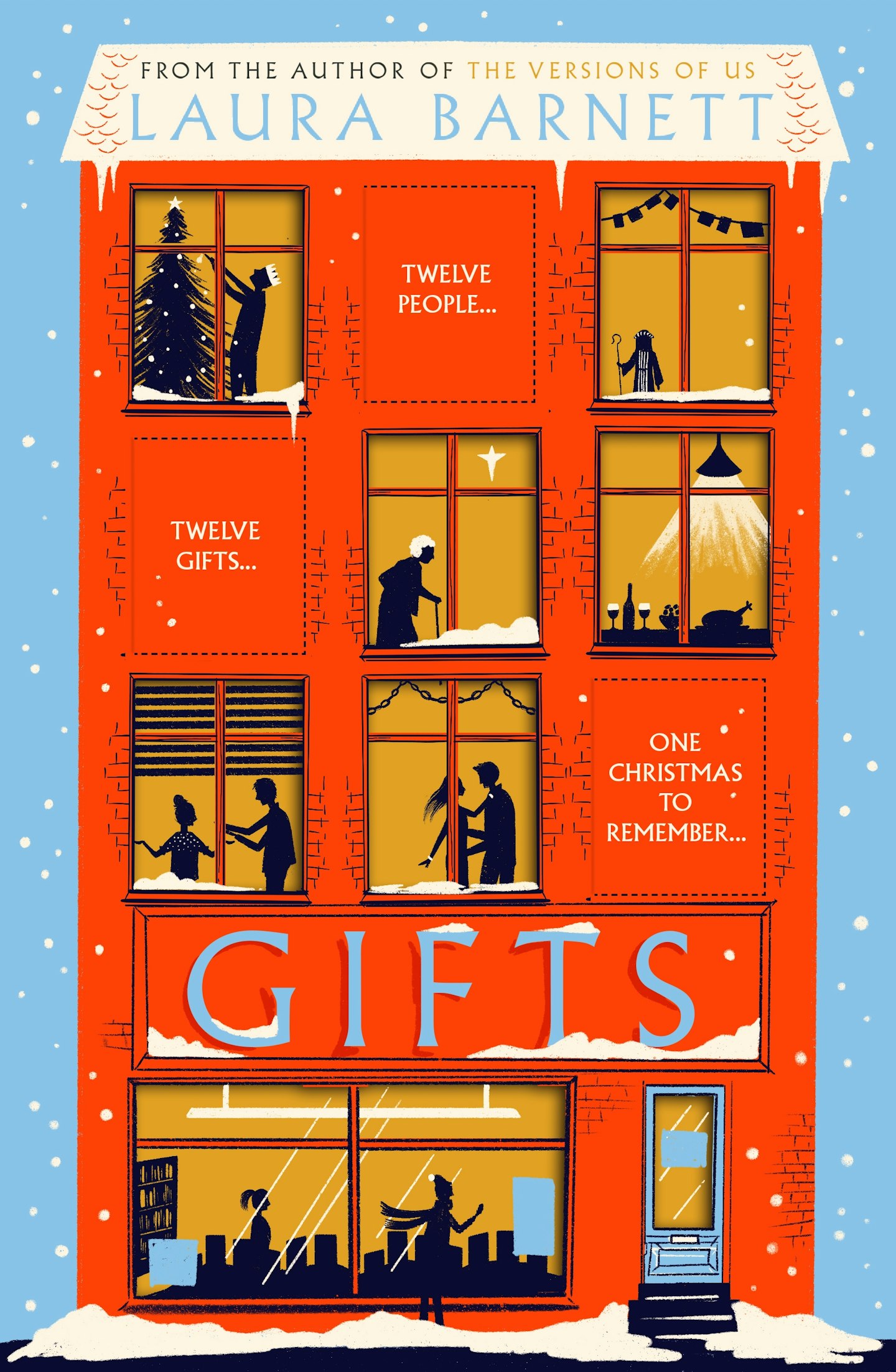

This conviction is at the heart of [Gifts](http://Gifts: https://www.weidenfeldandnicolson.co.uk/titles/laura-barnett/gifts/9781474624398/ ), my new novel. Set at Christmas 2021 in a Kent market town, the novel follows twelve characters as each chooses a present for the next. A festive paper chain of a book, if you like, exploring the joy and sorrows of the season, and the significance of finding a gift for someone we love, regardless of its monetary value.

Each of the characters is struggling in some way, as we all do – with loneliness, with finances, with unrequited love. And the novel is set against the backdrop of the pandemic, which has of course brought suffering on a global scale, and meant that Christmas 2020 was a muted celebration, with most of us separated from family and friends. But there is love there for my characters, too, and friendship, and moments of joy – as there are for most of us at Christmas, whatever is going on in the rest of our fractious, complicated lives.

Perhaps it’s because I turn forty next year, but it seems clear to me these days that if we don’t accept the basically fractious and complicated nature of almost everything, Christmas included, we set ourselves up for a life of frustration and disappointment.

If we don’t accept the basically fractious and complicated nature of almost everything, Christmas included, we set ourselves up for a life of frustration

I am a reformed perfectionist. Having spent decades wanting everything and everyone around me to be and behave in a certain way – and berating myself, above all, for not achieving my own impossible standards – I have finally accepted that perfection is neither possible, nor desirable: that it’s in the mess, the breakages, that the real stuff of living occurs. Or as Leonard Cohen put it far more articulately than me, it’s only through 'the crack in everything' that the light can get in.

So, this Christmas, whatever our circumstances, however wonderful or difficult life is right now – even if you, too, are taking your children to see your estranged partner’s parents this year – let’s take heart. Life is messy. Christmas is messy. But it’s also joyous, expansive, fun, and can, in most cases, be infinitely improved by the consumption of chocolate, mince pies and champagne (or whatever your tipple might be). And what, in the end, is not to love about that?

Gifts by Laura Barnett is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

READ MORE: Have You Got Early Festive Fever?