It is, I will confess to you and you only, dear reader, my party trick. Embroiled in a debate on pretty much anything, I will reach into my reserves of fiction I’ve read which relates to this subject, find some vaguely relevant detail — and present it as fact, no matter how patchy my memory, or outlandish the book once was. Yet while I have been caught out on many occasion (most memorably conflating evolutionary biology with a Just So story), one book which has not let me down is Hilary Mantel’s* Wolf Hall*.

What happened, happened, as far as the historical events go. Mantel has done her homework, so that while the dialogue is not literally true, one senses the truth in it each utterance, so immersed is she in the history of her characters. In her lecture on historical fiction, Mantel said: 'your real job, as a novelist, is not to be an inferior sort of historian, but to recreate the texture of lived experience: to activate the senses, and deepen the reader’s engagement through feeling.' But more importantly, historical fiction is a great way in if you actually want to give a shit about history again. It reminds you that history isn't about staid facts and learning dates by rote. It's about real (fascinating) people and their lives. And if you're looking for inspo, you could do worse than to start with these guys...

1. Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

Obviously. It’s a big book, but as British historical events go, you don’t get much bigger or more defining than the Reformation. Taking Thomas Cromwell as it’s protagonist — a controversial figure, to put it mildly — Mantel tells the story of Britain’s secession from the Roman Catholic Church with such breathtaking wit, energy and style, you don’t realise you’re learning. Like a thin, crisp, sourdough pizza, Mantel serves up all the best parts of Tudor fiction — the grandeur, the gore, the sex, the slander — in a way that is actually good for you, as well as tasting immense. From the very opening page you are in Cromwell’s head, literally: it opens with his blacksmith father kicking his head in while the young Cromwell slips in and out of consciousness. Remember this image. It defined him: and it will define your perception of a politician that, pre Wolf Hall, history remembers as ruthless, highly effective, and largely unloved.

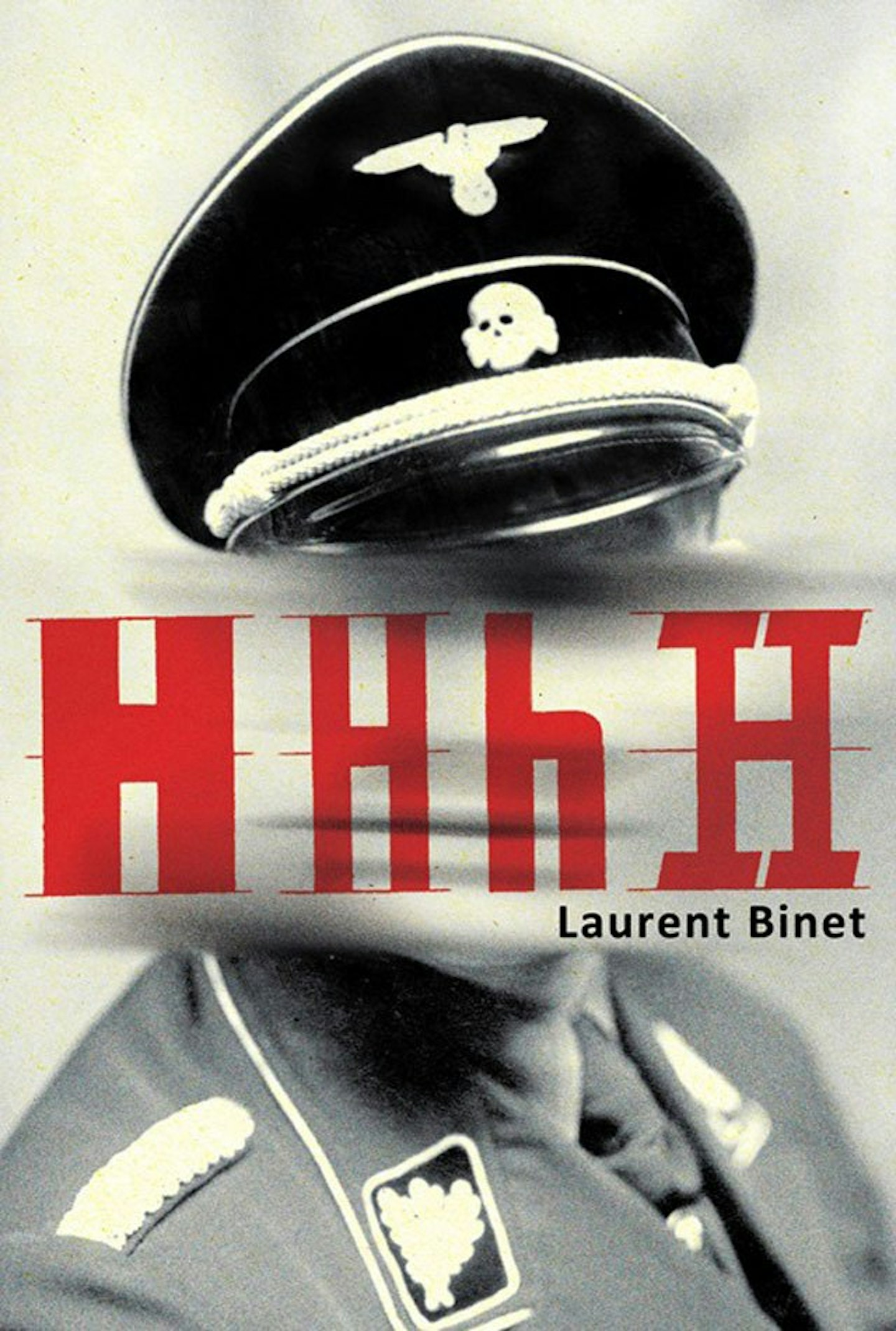

2. HHhH by Laurence Binet

Hang on to your knickers folks — things are about to get meta. Written a few years ago by a then unknown French author, Laurence Binet, this debut novel tells the story of a Frenchman telling the story of Reinhard Heydrich: architect of the Final Solution and Heinrich Himmler’s ruthless right-hand man. The premise of the book is a botched assassination attempt on the part of two Czech parachutists, in which the ‘author’ has developed an all-consuming obsession. It also charts the ascension of Heydrich, or H as he dubs himself (he was a big Bond fan, and liked M in particular) from budding musician to the Butcher of Prague: organising the Kristallnacht pogrom and leading the Wannsee Conference that put in motion the extermination of the Jews. This story alone would be enough, soaked as it is in blood, espionage and scheming, but the running commentary on what the author is writing — how true (or not) it is, why he’s including one bit of information and not another, why he’s chosen this or that form of dialogue — is also compelling, prompting you as the reader to question the nature not just of history, but of storytelling itself.

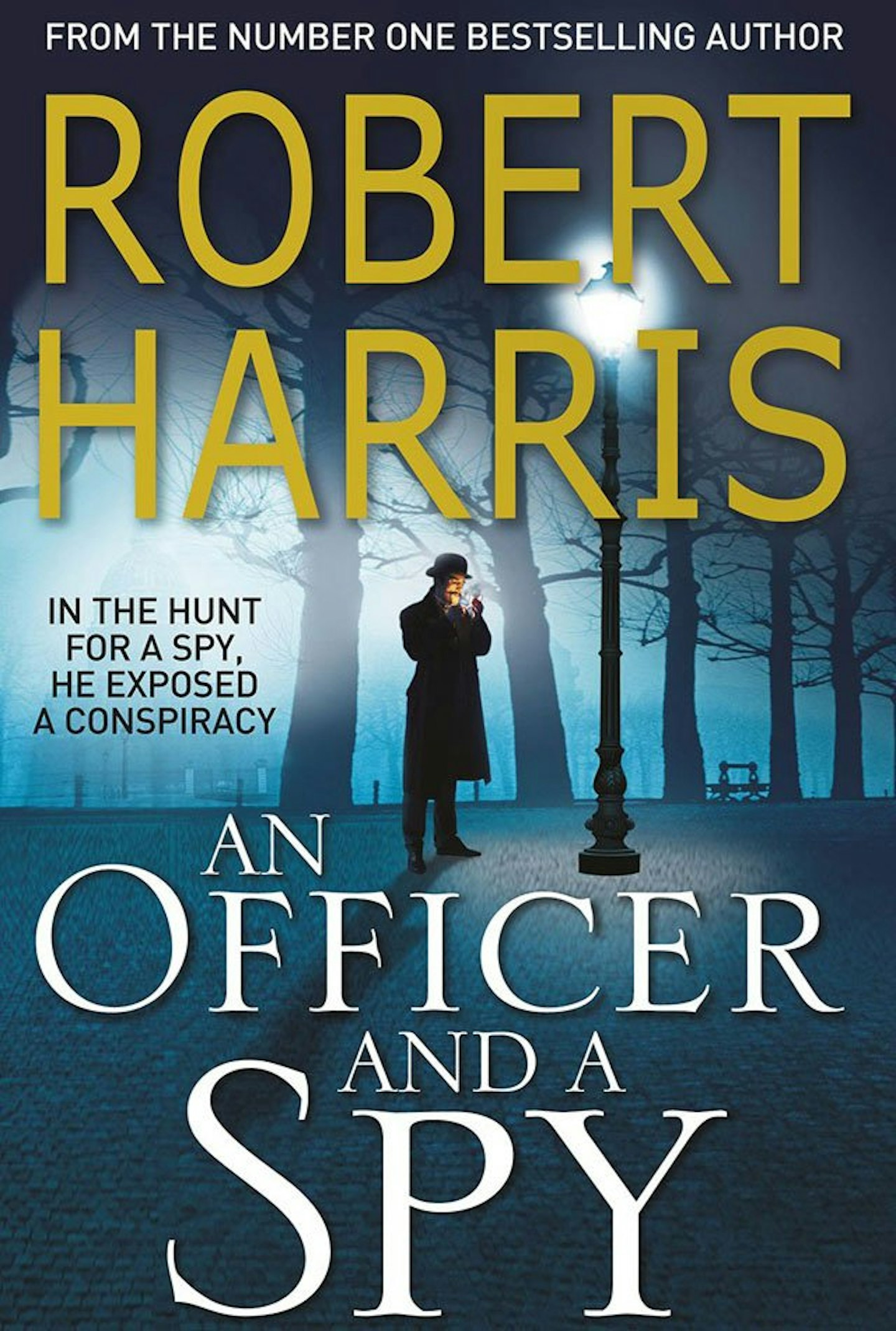

3. *Officer and a Spy *by Robert Harris

At the risk of judging a book quite literally by its cover, there is something irreducibly, well, male about Robert Harris novels. The size and font (Impact or Rockerfeller, surely) of the title and author, not to mention the graphic images, all scream Crime Thriller for Red Blooded Man. This is — or should be — bollocks. Ladies can have love crime thrillers, and the last time I checked, my blood was red also. Besides, Harris is an exceptional author whose works of historical fiction are well worth your commuting time. Officer and a Spy tells the story of the Dreyfus affair, through the eyes of the man who brought this case of outrageous anti-Semitism to light (and, ultimately, justice), Colonel Picquart. Harris has made his name writing alternative histories, but this is the real deal, drawing on court transcripts, newspaper reports and Dreyfus's own accounts. Not that you’d know this from the writing: this is a classic Robert Harris romp through 19th-century belle epoque Paris, and the aptly named Devil’s Island to which Dreyfus is ignominiously exiled. His protagonist is pitch perfect: cool, dry, sardonic — French, basically — and the parallels with modernity (think Guantánamo, Edward Snowdon, media injunctions) are understated but impossible to ignore.

4. Regeneration by Pat Barker

Yes, there is a film of the book. Yes, it stars Jonny Lee Miller. But before you reach for your Netflix tab, please take a moment to consider Pat Barker’s painstaking commitment to this Booker Prize-winning account of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon’s recuperation in a war hospital. Drawing extensively on period psychological papers, as well as the poets, own written accounts, it is considered by literary critics and survivors alike to be both historically and emotionally on point. It starts with Sassoon and his ‘declaration’ which results in his internment in Craiglockhart hospital, near Edinburgh. He has hallucinations — what soldier doesn’t? — but he is the model of sanity in comparison to the PTSD-torn shadows he finds within its sandstone walls. As with all good WWI novels, some scenes are devastating: men condemned to waking nightmares, the horrors of war playing in a hallucinatory loop in front of them. Yet with the stories of two of the century’s most remarkable poets, not to mention one of its most influential psychiatrists, woven into the mix, it is so much more than another perspective on the Great War.

5. Beneath a Scarlet Sky by Mark Sullivan

So I was trying to avoid going OTT with WWII. But when the most voracious consumer of historical fiction you know gets in touch to say ‘TELL THE WORLD ABOUT THIS BOOK’, you sit up and listen. Besides, how much do you know about life in Nazi Italy during the war? This window into it, in all its horrors, comes via the eyes of Pino Lella: a Milanese boy who ends up becoming the personal driver for Adolf Hitler’s left hand in Italy, General Hans Leyers, while simultaneously acting as an informant to the Allied forces and courting Anna, the girl with whom he has fallen hopelessly in love. It is the true story of a forgotten hero: one who, moreover, is still alive. Mark Sullivan’s research centres around talking to him, as well as vast amounts of historical data. In the words of my friend, it is 'such an amazing and heart-wrenching story, you'll keep forgetting it's true.'

6. I, Claudius by Robert Graves

The most recent edition of this 1934 tome comes with a recommendation from Hilary Mantel plastered across the front, so you know it’s legit. It is also one one the hundred best English-language novels from 1923 to present, according to Time. Given my knowledge of the Roman Empire is largely confined to Gladiator and Anthony and Cleopatra as presented by Richard Taylor and Elizabeth Burton, this account of Roman Emperor Claudius was pretty illuminating. But even those who took Roman history beyond the colouring in mosaics stage at school will find enjoy having it taught to you by 'I, Tiberius Claudius Drusus Nero Germanicus This-that-and-the-other (for I shall not trouble you yet with all my titles)'. In this, his autobiography, nobleman Claudius surveys the bloody purges and breathtaking cruelty of his predecessors Augustus, Tiberius and Caligula with a level of irony, wit and self-deprecation that makes Rome’s most unlikely Emperor a genuinely likeable raconteur.

7. The Sealed Letter by Emma Donoghue

Apparently, the Codrington Divorce of 1864 is very well known. Suffice to say, I’d never heard of it, until my historical-novel-loving friend recommended this elegantly gripping account of it from The Room author, Emma Donoghue. The novel opens with Helen Codrington, the unhappy wife of the governor of Malta, returning to London and bumping into her old friend Emily Faithfull: a journalist and committed feminist whose role in the subsequent divorce proceedings ultimately makes a mockery of her name. This is no neat literary device: Emily — ‘Fido’, for short — Faithfull really existed, in all her nominative irony. So too did the Codringtons, and the cold, ruthless tyranny of the Victorian marriage laws to which they fall victim. Those looking for a highly addictive, heart-in-the-mouth history lesson into first wave feminism and Victorian court, your quest ends here.

8. Tulip Fever by Deborah Moggach

A rogue entry this, not least because the long-awaited, much-hyped Hollywood translation released last week appears to have fallen on thorny critical ground. 'More a light sneeze than a fever,' sneered one critic — but if that’s your opinion of the film too, I implore you: do not write off Deborah Moggach’s book. Tulip fever — or tulip mania, as it is historically known — is one of the most extraordinary episodes in history, both in its excesses (at the height of Amsterdam’s bulb market bubble, one single, rare bloom could fetch 10,000 guilders — enough to feed, clothe and house a Dutch family for decades) and in its mortifying insight into the human psyche. Historians consider it to be the first example of an economic bubble. That parallel is interesting, but for my part it is the hysteria the humble plants whipped up that is so interesting: and it is this that Moggach’s account of the period so astutely captures: an account that revels in fiction (you can’t, let’s be frank, have a book called Tulip Fever and not having a steamy great love affair between a painter and his subject), but is rooted in fact.

9. Day without End by Sebastian Barry

Another story that deals in facts while dabbling in fiction, Days without End is currently sweeping the board of literary prizes. In it, Barry does for American civil war and the complex interactions between settlers and the indigenous population what, in a Long Long Way, he did for the Great War. That is, he floors you with it. Thomas McNulty has fled the Irish famine, and wound up in Missouri. To say he and his countrymen were unwelcome is an understatement: 'Nothing people… Nothing but scum,' he says of America’s opinion on them; and this same astute, striking yet slightly surrealistic voice continues throughout the novel, narrating his relationship with his friend and lover, John, their journeys over the lawless American outback, and conflicts with American Indians that leave men on both sides 'making the noises of ill-butchered cattle.' Thomas and John’s day’s may be without end, but it’s something of a relief to your frayed nerves that this book has one.

Like this? You might also be interested in...

In Praise Of The 'Hot Mess': The Fabulous, Messy History Of Flawed Female Characters

Follow Clare on Twitter @finney_clare

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.