Living Underwater By Kati Van Der Hoeven: I’m looking out of a window. No one sees me from outside. I’m calling. No one hears me. I’m throwing my fists against the glass. No one notices. I wake up.

This is the only dream I’ve had since the stroke that isn’t nice. But it is how I feel, trapped inside myself. It’s a life where only the computer hears me, only the screen sees me. If I thought I’d live like this forever – dramatic, emotional and self-conscious – I think I’d die of despair.

I didn’t literally dream this; it’s a nightmare I imagine while I am fully awake. Not every day, but some days. My dreams are actually about modelling days, and walking along the California beaches. Some of my dreams are real memories, some are just nice situations of what could be. None are about entrapment. I guess my subconscious has a way of dealing with this situation by letting me remember and relive movement and sound. Always I look for the positive, at least in real life I can see, I can hear, I can feel. Just because I can’t talk, or move, or touch doesn’t mean I’m not alive. I just have to learn to live differently. At least this is what I tell myself. This is how I go forward. This is how prepare to leave the rehabilitation centre in Helsinki to return to Mikkeli, Finland, my childhood home, to the cold darkness of Finnish winter. Well, at least it’s summer, and it won’t be cold for another couple of months.

This morning I’ve been left alone for a few minutes. It won’t be for long because a nurse will come in soon – totally alone is rare in the daytime, but she just left me in the bathroom for a moment. I look up and there I am. For the first time since the stroke, I look into a mirror and see myself. I remember when I could not even lift my chin. Ziti offered to hold her compact for me, so I could look in a mirror. But I closed my eyes. She brought a hand mirror. I blinked, “No”. She gave up after a few more tries. But today it is time.

When I look at this face, I see a girl I don’t recognise. I look older. My hair is brushed – the nurses here are very careful to do that for me. My face looks clean and there is a bit of make-up, done well, around my eyes. It’s not the make-up I would wear though. She hasn’t put on any lipstick yet. The worst thing is, my face is round, fat! It’s awful, staring at a fat face, a fat woman, who used to be super skinny, sleek and beautiful.

Who is Kati Lepistö now? A fat cripple. But no! That’s not all of me. I’m still a woman with a heart and a soul. I still long to be held, long for sex. I still love clothes (naturally), and food (more than any self-respecting model ever should).

The people here at the clinic have tried really hard and have helped my medical situation a little. But my heart is broken and my soul is empty. How do you fix an empty soul? No one else can. I have to fix it myself. Today I’m going home. It will be safe, but I’m so scared. While I’m staring at my face, like all the other people have been staring at me for the last five months, I tell myself what I see: I see a person sitting in a wheelchair. She’s fat, but she wouldn’t be if she could walk. What else? Oh God, I don’t know. Oh, I don’t know. I have a name and a face and a useless body, but I don’t know who I am!

Then the howling starts. Damn! I won’t be alone now. I liked being alone, and I’ve ruined it because I can’t control myself or stop myself from howling.

Leena comes in. I’m glad it’s Leena.

“Kati, are you okay?”

“Yes,” I blink. I don’t know who I am, but I know I’m okay.

Residential rehab is over and it’s time for goodbyes. Leena smiles: “Kati, as we finish here, I think you can reward yourself with a little trip. Maybe you’d like to take a short cruise to Norway or Sweden. It isn’t too far, and shouldn’t be too tiring. What do you think? A change of scenery would be good for you, and the air will be very healthy.”

I’m the best I’ll be, they think. I can’t talk, I can’t walk, I can’t even move. But I can travel. Well, baby, this girl is gonna travel!

“We’re going to Florida,” Mom tells them.

Hot sun, palm trees and happy faces! That’s where we’re going. The staff stare at us as if we’re insane. Well, if we are, so what? Life is to be lived, made the most of. I’ve been cooped up here with a death sentence, so it’s time to roll and go. And so we will, very soon. Sure, there are some practical things to organise at my parents’ house: assistance, accommodation changes, but a holiday is in order and yes, we are going to go for it.

All the physiotherapists, led by Riitta and Virpi, come to my room to say goodbye.

“She was our most challenging case ever,” says Riitta to my parents. “No one has ever worked harder, and it was so rewarding for us to work with her. We all think so.” There are nods and applause. I start to cry, laughing like a donkey at the same time.

There are many, many hugs. Even my dad hugs some of the nurses that he knows. He’s changed so much since the stroke. He’s always been caring, but he shows it in a tenderway now. I cannot even say I look out the back window as we drive from that place, since obviously I cannot even turn around. I’m scared, not knowing what the future holds, and so a bit of involuntary howling comes out of me as we drive. Thats the funny thing about my condition – I can’t hold it in even if I try. I guess we’d all better prepare for random outbursts.

I think I’m ready to move back home, but when we get to the driveway, I start to shake. Terror sweeps over me, and panic and despair, and helplessness. I’m going home to what? I’ve lost everything: my modelling life, my possessions – my pearl green Cadillac, my independence. As I’m wheeled to the door, I feel worse than I ever imagined possible. I’m moving back home, like a little girl who can’t make it in the world on her own. Jeez, can’t even walk in the door of the house where I grew up.

The howling starts. I feel like a dying animal about to be put down, but doesn’t want to – wait! On the other hand, I think I would celebrate it. I have no plans. What am I doing here? What will I do with my life? Nothing. I’m only going to waste my time and my parents’ time. Just sitting. That’s my future. Just sitting silently, unless I get to howling like I am now.

Oh!!!!!!!!!!!! OWE!!!!!!!! HOWL!!!!!!!!!

“Florida,” my mom shouts over the noise, my noise.

“Florida, Kati. We’re going to Florida, remember?”

“Florida, Florida,” my dad chips in.

My noise stops. Silence. They look at me.

“Ah,” I say. And then we all laugh. Yes, we are a crazy bunch. It helps.

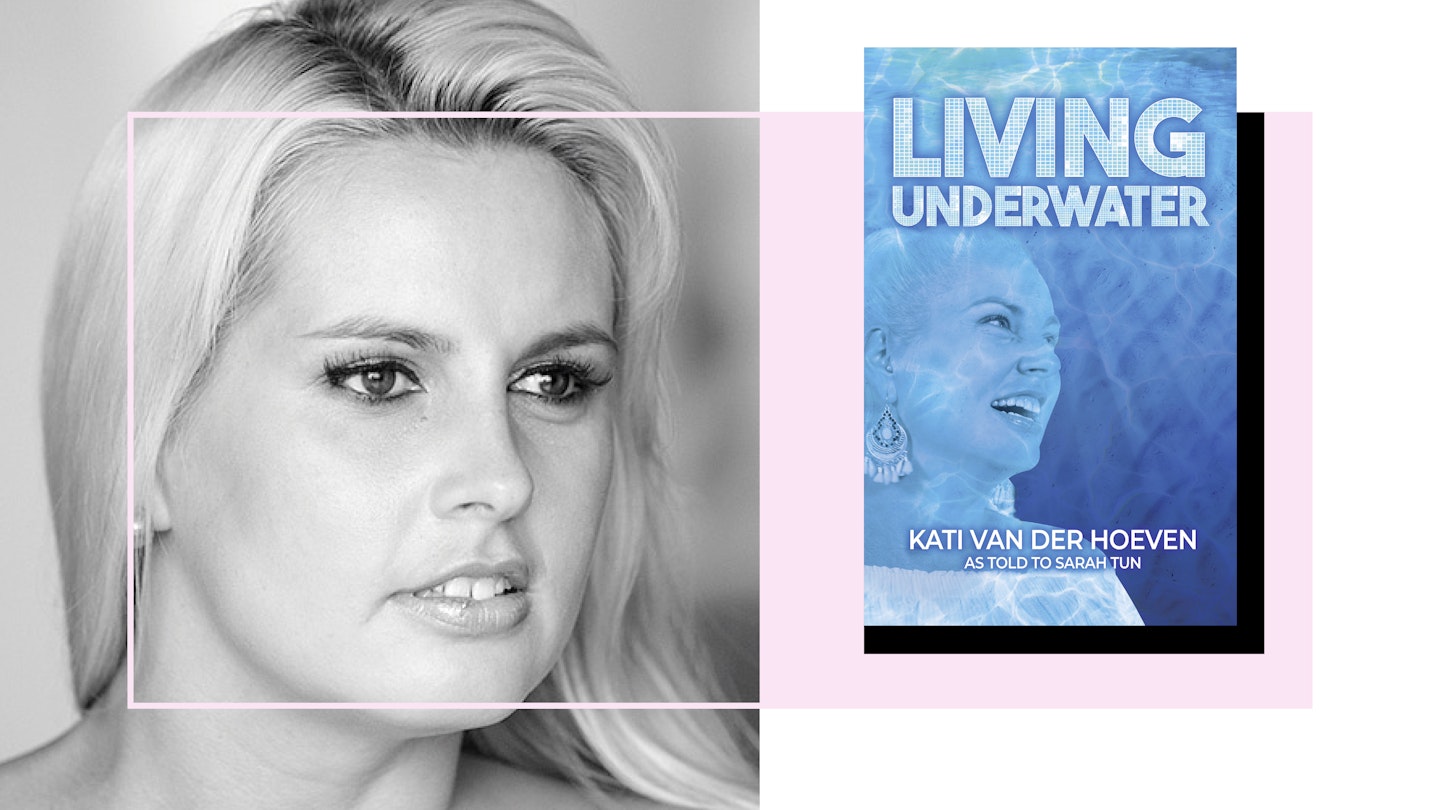

About The Author:

Kati Van Der Hoeven is a 42 year old former Finnish supermodel who 20 years ago had a stroke that went undetected. As a result, Kati developed "locked-in syndrome" - a catastrophic condition affecting the brainstem. She is completely paralysed and cannot move or communicate verbally except for vertical eye movements and blinking.

Kati went from being a successful, glamorous model who travelled the globe, who had the world at her feet to being a prisoner in her own body.

There is no specific treatment for locked-in syndrome. 90% of those with this condition die within the first four months. Kati's book tells the story about being one of those that belong to the 10%. But the path to surviving, thriving, building a career out of giving motivational talks and even finding love did not come easy.

You can purchase Kati Van Der Hoeven's book here.

Grazia Book Club is a new Sunday series, where we'll share an extract from a book that we're obsessed with and that we think you'll love. You can share your thoughts on the book by using #GraziaBookClub.