I’ve never smiled again like I did on my sixth birthday,

looking into the camera while my foster mother guides

my hand through a symbolic slashing of years. I can feel

the failing elasticity in her hand and smell the dissolving

lungs on her breath. My foster dad, a quiet favourite, dozes,

tired from a job I’ve never known him to have. Some kids

are only here for summer. I watch them, unconsciously

thumbing my singed skin, a scar from separated kin, a

melding with warmth severed too late, and remember

what loss feels like, deciding to stay around faces await-

ing the same school as I am. I’ve crunched through

several chocolate cornflake cakes before I remember I

have presents to unwrap. I walk to the gifts, eager but

satisfied, tonguing the soft cereal stuck to my teeth.

I notice the handwriting on the first present and retreat

to my foster mother’s leg. ‘All right, dear, we’ll open this

one later.’

/

My mum carried around the ultrasound now come to

life – an image swollen with my future – to show me

nothing’s black and white. I imagined a fragile sticker on

her stretch-marked stomach and always walked behind

her as she climbed the stairs. We’d fall asleep together,

me supposed to be watching over her but getting caught

up in the lethargy of her movements. I would wake before

her and lift the kente from her stomach, the cloth getting

acquainted with who it’d hold up, and imagine the smile

of my soon-to-be sibling. And as I’d fall back to sleep I’d

ask the bump for their name and glide my fingers over

stretches and paths, trails to a world and a body’s resist-

ance to the light. Dribbling in the womb became spittle

in a bucket, only my hands touched it, and pouring it out

was simply wiping the baby’s mouth. When my father

walked out, I walked in, with a Cornetto in one hand

and my pocket smelling of Deep Heat. Then my mum

grabbed my hand so I could feel the kicks, but as I touched

her stomach I knew it was a palm trying to connect with

me through the skin, and my bond with my brother

touchingly began.

/

I watch a little black boy standing outside a shop, pre-

tending not to be bothered by his white friends inside

spending money. I walk over and give him a two pound

coin and remind him to eat whatever he buys before he

gets home. My mum wouldn’t approve so I know his

mum wouldn’t either. Wide, his eyes look like mine and

I fall in love with how grateful everything about him

becomes. ‘Safe, man!’, he says. He smells like cocoa but-

ter and DAX and I follow his scent up to the door and

watch as he stands in front of the colourful sugars with

snappy names. I know he’s savouring being spoilt for

choice; I’m sure when he takes a bite of whatever he buys

I too will be satisfied. And a memory comes back to me

of the first time I held a pound coin, given to me by a

stranger who smelled like cigarettes and Blue Magic.

/

We sleep in the same bed long after I should have grown

into my own. I kneel on the mattress cornering my

mum, asking why she sent me away, why she allowed me

to be raised by people whose lives were so different from

our own, people she didn’t even know. My side of the

bed is still tender with my silhouette. My mum reaches

over to my indent and tells me not to speak ill of the

dead.

She trusted me to keep her alive, to deify, to render her

an immortal that cancer couldn’t metastasise. Thousands

of stacked monitors going out one by one, a memory on

each and then darkness to close the scene. Most of our

loves die lying – dropping out of time, leaving broken

promises behind. Mum, I thought you wanted to stay.

But instead, when I turn back, I see, you were like me

but you did it by smoking twenty a day. Why choose to

die? I could have saved you, with my towel safety-pinned

around my neck, a Boy Wonder wondering how to defeat

the evil smoke monster rising to the ceiling. Lose a mem-

ory and you’ve lost a life – so hands stretch into the

darkness to bring our living thoughts to the light. Shak-

ing the limbic like a Polaroid until the image is clear,

I stare at the face I think I remember, confused as to why

you’re not here. If I forgive your absence, then you have

to forgive mine, forgive me for not showing up and for

struggling to keep you alive. And though we’re not in

contact, you’ll always be my mother; we’ll meet again

because we never said goodbye.

Book Club questions:

How do you feel about the style of the writing? Why do you think the author chose to write in this way?

What can you tell about the narrator’s relationship with his mother from just this extract? What questions do you have?

Which of the above four verses sticks with you the most? Why?

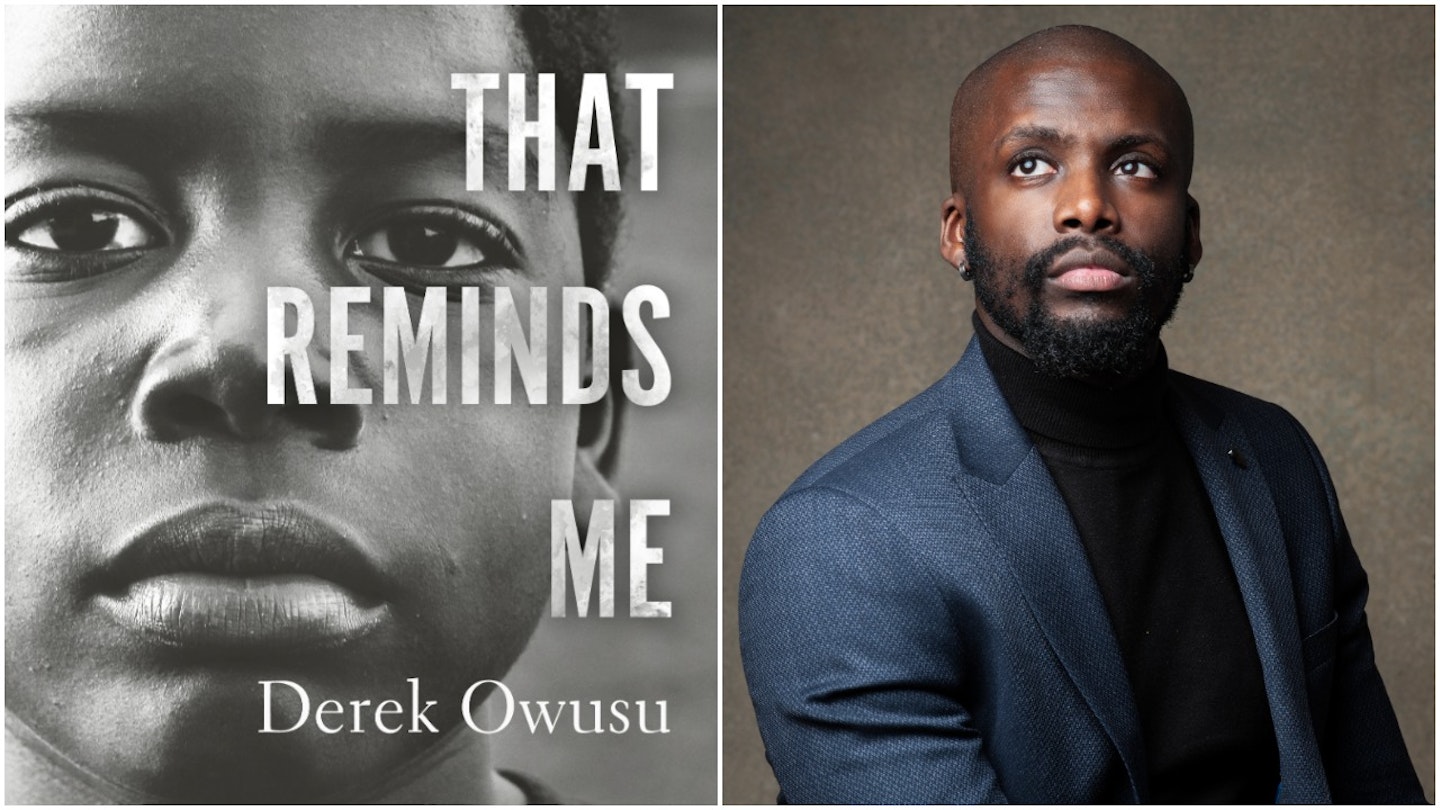

That Reminds Me by Derek Owusu is published by #Merky Books, hardcover £12.99. Buy now from Amazon or your local bookshop.