I have no problem with telling you that I'm ever so slightly nervous about interviewing Chris Kraus. She is in London promoting her new book, a biography of postmodern slashie Kathy Acker, a New York poet, playwright and novelist who was central to the city’s punk movement in the late 70s and early 80s. Prior to speaking with her, the feeling I had was similar to the waves of nausea I would get while walking to tutorials at university, contemplating everything I didn’t know.

I had heard about what is now, arguably, Kraus’s most famous work - I Love Dick- long before I had read it. At this point in time, it was mostly discussed in academic circles and amongst the art history students, I was knocking about with (Kraus was first and foremost an experimental filmmaker, a writer second but she is now far better known for her writing). I didn’t know much about Kraus or her work but I was, like most people, drawn in by the provocative title. I wanted to be part of the conversation, of whatever it was everyone else was so excited by. It was the same feeling you get when someone casually drops that they knew where a ‘cool illegal rave’ is in conversation or shares pictures from an exclusive party that you weren’t invited to.

**WATCH NOW: The Debrief Goes To The Miss England 2017 Final **

For the uninitiated, I Love Dick is a novel written in the form of letters. It is about a woman artist, called Chris Kraus, and her unrequited love for Dick, a cultural critic. Chris and Dick meet over dinner at Sushi restaurant in Pasadena, which they share with her fictional (but also real life) husband Sylvère Lotringer. The letters are all written by fictional Chris and addressed to Dick. He only responds once, but in Part II there is a one night stand. Dick is, apparently, a real-life academic by the name of Dick Hebidge who is said to be ‘appalled’ by Kraus’s use of his name. The book is at once theoretical and visceral, intellectual radical and an exercise in gossip; Kraus describes her particular brand of confessional writing as ‘lonely girl phenomenology’. But, when all is said and done, it is a book about power in male-female relationships and that is why it speaks to so many people.

I Love Dick was then, finally, published in the UK for the first time by Serpent’s Tail in 2015. The title, writ large on the cover in chunky white and pink text, lent itself perfectly to Instagram. It’s the sort of book that makes people look at you, sometimes even provoking them to ask you what you’re reading or make a bawdy joke about the title. Kraus’s private joke, between writer and reader, relies on being exhibited in public to be funny and so it made the perfect post, my feed was soon full of it. I read the book in 2016, nearly two decades after it was first published in 1997 by Semiotext(e), a painfully cool independent publisher that put out the work of postmodern avant-garde artists and philosophers like Deleuze, Guattari, Foucault and Jean Baudrillard. That’s when I understood why everyone had been talking about this book.

I ask Kraus if she was surprised by the attention* I Love Dick* got when it was re-released? What does she make of headlines like ‘when classic turns cult’ which are often put on top of pieces about her? ‘In terms of attention, I never felt shortchanged when the book first came out in 1997’ she says. At the time of its initial publication, the book was divisive and, to me, it seems these days its taken very seriously? ‘Everyone in the art world read it, and they were either For, or Against it. But I did wish at the time that people would take it more seriously as writing, rather than just focus on controversy’ Kraus says, ‘twenty years later, the audience is much larger, because things spread out wider and faster through social media, but the thing that’s made me the happiest is that people now recognize I Love Dick as a book that was consciously written. In 1997, one critic described it as “a book not so much written as secreted”!’ It’s hard to imagine anyone being quite so damning of the book now, accusing it of being the product of uncontrollable bodily fluids seeping out onto the page as opposed to a deliberately crafted critical comment on the way men and women interact.

In a way, though, I say, isn’t that the point? Wasn’t it quite fitting that so many people ‘didn’t get it’? The book is about the insecurities and frustrations young women feel, particularly those working in creative fields because that is the backdrop. Does it say something about how the cultural landscape, particularly in terms of feminism, has changed in the last 20 years that the book now resonates with a younger audience? ‘Well,’ Kraus says self-deprecatingly, ‘I think it’s the title that makes it so good for selfies! People take pictures of their pets reading the book. But, when people get into it and talk about it to their friends, I think it’s for exactly those reasons. There’s so much pressure for young women to succeed at everything, and simultaneously. I Love Dick gives people permission to fail, or rather, be human.’

And, does she think the experience of being a young woman has changed in the last 20 years? In the West, particularly the US and the UK, intergenerational inequality is hailed as one of the most pressing issues faced by society, often in reference to how it is affecting creative industries (which in my view is not the most important aspect of the crisis but it is, nonetheless, a factor). It’s no secret that Kraus herself is a landlord. She has always been honest about it. Has she thought much about how housing in particular plays into the inequality young people face, particularly those who may want to pursue creative work which isn’t always initially lucrative? ‘My real estate work has always been property management, not speculation’ she says, ‘I’ve never flipped houses – I think it’s sociopathic. Over a decade ago, I bought four low-income apartment buildings in Albuquerque, New Mexico, fixed them up, and continue to manage them.’ Property is, for Kraus, ‘a day job’; ‘until the last couple of years’, she says ‘there was no way I could support myself with part-time teaching and writing’. Her candidness is a refreshing rejection of the starving artist trope which, as anyone who has ever tried to cultivate it knows, is actually impossible to nail unless you have wealthy parents or benefactors of another kind behind the scenes. Today there is, despite all the economic and financial problems we face, a reluctance to be real about this. There's probably a gap in the market for a contemporary version of Virginia Woolf's A Room Of One's Own which talks about how a woman must have a money making job if she is to do anything creative.

Kraus points out that the question of housing inequality, ‘of the transformation of international cities into metropolitan centers of wealth – it’s not necessarily generational.’ She points out that ‘in the late 1970s and 1980s, whole swathes of London, New York, Paris, LA, were places nobody wanted and left to the poor. Of course, artists moved in, because it was so cheap to live there. And the value of apartments and houses that people bought during those years has grossly appreciated. These cities are now unaffordable for anyone moving to them without private wealth. It would be impossible for even an upper-middle-class professional person without resources beyond her own salary, to save up enough for a down payment. This transformation of cities into wealth centers occurred through forces beyond the artists and writers who happened to buy their own places 20 or 30 years ago.’

Kraus is right that the way our countries function is changing, people are moving away from traditional cultural hubs like London or New York and, in Britain particularly, out into places like Margate, Glasgow, and Bristol. ‘I’m very interested in art projects being done outside the main centers’ Kraus says, ‘that’s where I think things are more possible.'

Does she see any other changes in creative fields? Particularly when it comes to women’s place in them? ‘Women are definitely more present and prominent as artists and writers than they were when I moved to New York in the late 1970s’ she says. ‘The people a half-generation older than me were trying to navigate what the rules were, in the wake of “the sexual revolution.” Mostly, it seemed, that it led to the imperative for women to be sexually available at all times without any demands or expectations. Not so great.’ The most positive change, as she sees it, is that ‘younger women’ today ‘have forced questions of courtship, love, and coupledom into the larger culture, refusing to let them be marginalized as “women’s questions.’ You only have to look at the fact that a show like GIRLS was ever made, let alone its success, to see that. It’s no coincidence that Lena Dunham is a fan of Kraus, it makes sense because in many ways her work paved the way for the confessional genre that Dunham took mainstream and, in turn, you might argue paved the way for a new generation to connect with Kraus’s work. Her style also set the scene for a new kind of women's writing, which is seen in the work of someone like Sheila Heti whose novel How Should A Person Be? is surely also an exercise in 'lonely girl phenomenology' if ever there was one.

There’s no doubt that a lot has changed, then, since* I Love Dick* was written but I wonder if Kraus thinks there has been much change when it comes to the power balances and, more importantly, imbalances between men and women? ‘Not enough!’ she says unequivocally. ‘Reality TV shows exaggerate these stereotyped gender divisions even further. The only way that it changes is when people refuse to participate. It seems like these imbalances are less pronounced in other cultures, like Scandinavia, where people’s sense of themselves is more secure, and they’re not performing a gender parody.’

I tell Kraus that there was a particular part of I Love Dick that has stayed with me. It talks about how we, as women, are often treated when we talk about our relationships. When we divulge the details of how we are being treated, good or bad, by our lovers and partners we are labeled, as she writes, 'bitches, libellers, pornographers, and amateurs'. Fictional Kraus’s riposte to this is to pose the question: 'why does everybody think that women are debasing themselves when we expose the conditions of our debasement'. It strikes me that this question still very much need to be posed, as publically as possible, particularly when it comes to calling out sexism. Does she agree? ‘Yes, I do’ she says, ‘but hopefully with a sense of perspective. Radical second wave feminism questioned the very things that women were competing for. The idea that feminism seeks not just parity, but a change in values, is worth maintaining.’

Questioning the role and aims of feminism feels more necessary than ever, I say. Unlike much of the #inspirtational feminism out there right now, I Love Dick captures the longing that I have always felt as a young woman, which all too often has gone hand in hand with a sense of failure. Longing to have a certain kind of relationship or career, and failing to achieve it. I explain that I sometimes worry that contemporary feminism doesn't allow us to feel like we have failed or are failing, it doesn't allow us to feel frustrated by sexism or long for a better job. We’re supposed to be smiling, all the time, or angry and combative. We’re #girlbosscheerleaders who never feel defeated and can do anything we want. But isn’t failing and feeling despair because you can’t have what you want an important part of evolving as a person? Chris simply says, ‘exactly!’.

All of this, finally, brings us to Kraus’s new work, the Acker biography. How does she see Acker’s work living on in a new context? ‘In 1975, Acker’s frenemy (Acker often turned friends into enemies) Constance DeJong wrote in her book, Modern Love: It’s 1975 and I can say and do anything I want. I want to prove this’ Kraus says, ‘around the same time, Acker often referred sarcastically to the whole glorious sexual revolution. Definitely, there was a double standard. Women were free … to have emotionless sex on demand, which wasn’t a great step forward.’ ‘Acker and others’ Kraus says ‘were brilliant about this’ and it still very much feels like a live question today.

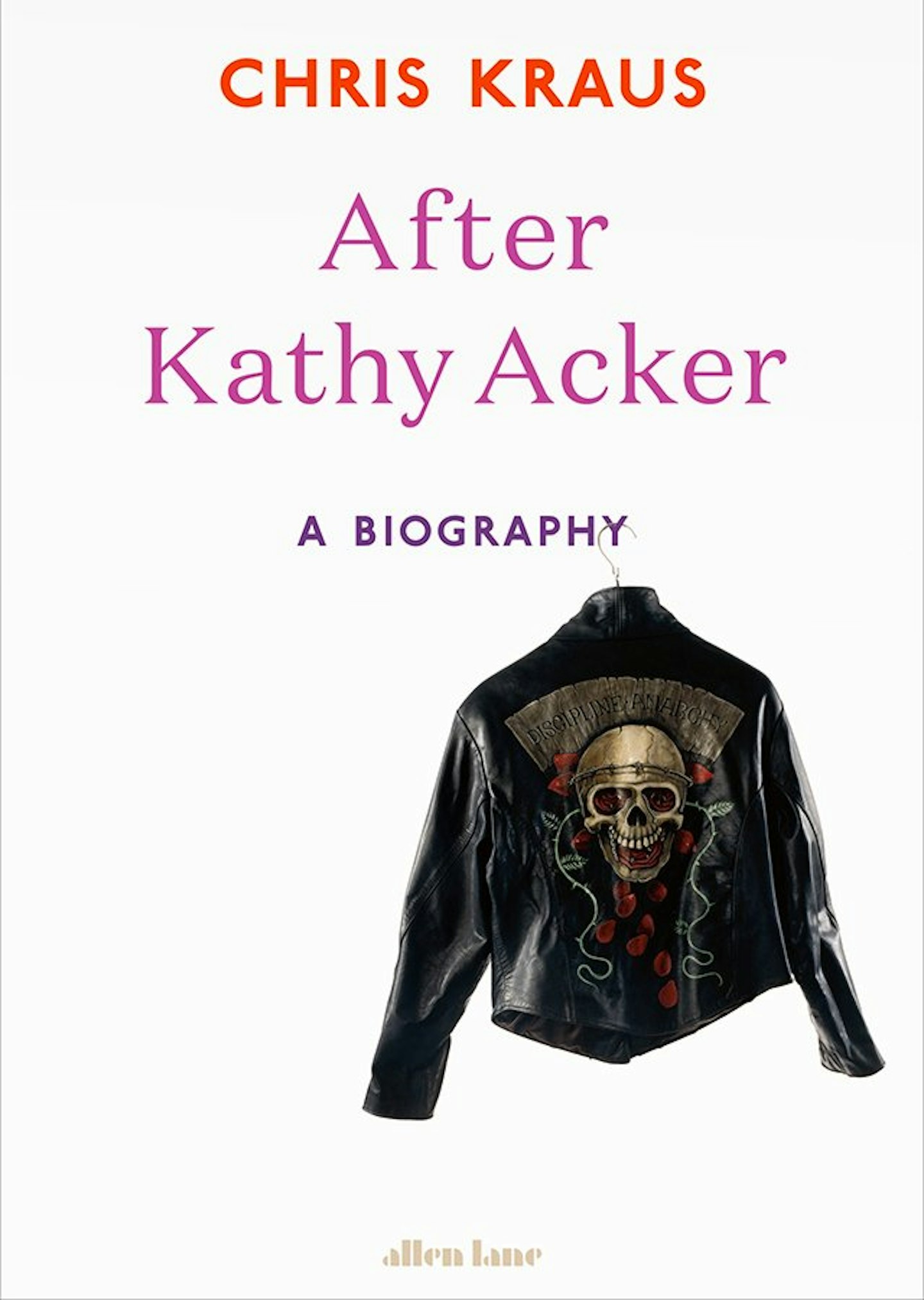

**After Kathy Acker: A Biography by Chris Kraus is published by Allen Lane (£16.99). **

Main photo: Carissa Gallo

You might also be interested in:

Follow Vicky on Twitter @Victoria_Spratt

This article originally appeared on The Debrief.