White people can be exhausting. Particularly exhausting are white people who don’t know they are white, and those who need to be white. But of all the white people I’ve met—and I’ve met a lot of them in more than three decades of living, studying, and working in places where I’m often the only Black woman in sight—the first I found exhausting were those who expected me to be white.

To be fair, my parents did set them up for failure. In this society where we believe a name tells us everything we need to know about someone’s race, gender, income, and personality, my parents decided to outwit everyone by giving their daughter a white man’s name. When I was growing up, they explained that my grandmother’s maiden name was Austin, and since her only brother didn’t have children, they wanted to make me the last Austin of our family line.

Sounds beautiful, right? Well, it is. It just happens to be half the story.

How did I discover the other half? Through my exhaustion with a white person. We were in my favourite place—our local library, built in a square with an outdoor garden at the centre. At seven years old, with books piled high in my arms, I often had to be reminded how many I had already checked out when it came time for our next visit. I am certain my family singlehandedly kept our library funded. We checked out so many books at a time, we would find them under the car seat, between the cushions of our couch, or hiding under the mail on the table.

On this sunny Saturday afternoon, as I stepped up to the front desk to check out my books, I remember the librarian taking my library card and scanning the back as usual. I braced myself, expecting her to announce the fine I owed for the week.

Instead, she raised one eyebrow as the other furrowed and asked, 'Is this your card?'

Wondering for a split second if I’d mixed up my card with my mother’s, I nodded my head yes, but hesitantly. 'Are you sure?' she said. 'This card says Austin.'

I nodded more emphatically and smiled. 'Yes, that’s my card.' Perhaps she was surprised a first-grader could rack up such a fine. But when I peered over the counter, I saw that she still hadn’t opened the book covers to stamp the day when I should bring them back (emphasis on should). I waited.

'Are you sure this is your card?' she asked again, this time drawing out sure and your as if they had more than one syllable. I tilted my head in exasperation, rolling my eyes toward the popcorn ceiling. Did she not see all the recent books on my account? Surely this woman didn’t think I didn’t know my own name.

Then it dawned on me. She wasn’t questioning my literacy. She was another in an already long line of people who couldn’t believe my name belonged to me. With a sigh too deep for my young years, I replied, 'Yes, my name is Austin, and that is my library card.' She stammered something about my name being unusual as her eyebrows met. I didn’t respond. I just waited for her to hand my books back to me.

My check-outs in hand, I marched over to my mother, who was standing in the VHS section with my little brother. I demanded that she tell me why she named me Austin.

By then, I had gotten used to white people expecting me to be male. It happened every first day of school, at roll call. The boys and girls automatically gravitated to opposite sides of the room, and when my name was called, I had to do jumping jacks to get the teacher’s attention away from the 'boys’ section.' So how did I know this wasn’t more of the same? The woman’s suspicion. Because, after I answered her question about my little library card, I still was not believed. I couldn’t have explained it at the time, but I knew this was about more than me not being a boy.

'Why did you give me this name?' I demanded, letting my books fall loudly on the table next to us. My mother, probably wondering how she’d managed to raise a little Judy Blume character of her own, started retelling the story of my grandmother and the Austin family. But I cut her off. 'Momma, I know how you came up with my name, but why did you choose it?'

She walked me over to a set of scratchy green armchairs and started talking in a slow, soothing voice. 'Austin, your father and I had a really hard time coming up with a name that we both liked. One of us thought to use your grandmother’s maiden name—her last name before she married your grandfather.' I already knew this part of the story. I swung my legs impatiently, waiting for her to tell me more.

'As we said it aloud, we loved it,' she continued. 'We knew that anyone who saw it before meeting you would assume you are a white man. One day you will have to apply for jobs. We just wanted to make sure you could make it to the interview.'

My mother watched my face, waiting for a reaction. My brain scrolled through all the times a stranger had said my name but wasn’t talking to me. In every instance, the intended target had been not only a boy but a white boy. I didn’t quite understand my mother’s point about job applications—to that point, the only application I had filled out was probably for the library card in my hand. But one thing became clear. People’s reaction to my name wasn’t just about my gender. It was also about my brown skin. My legs stilled. That’s why the librarian hadn’t believed me. She didn’t know a name like Austin could be stretched wide enough to cloak a little Black girl.

As I grew older, my parents’ plan worked — almost too well. To this day, I receive emails addressed to 'Mr. Austin Brown' and voice mails asking if Mr. Brown can please return their call. When I am being introduced to new people, there is often an attempt to feminize my name ('You mean Autumn?') or to assign my name to my husband. And though I usually note that I am a Black woman in my cover letters, I nonetheless surprise hiring committees when I show up to the interview in all my melanin glory.

Heading into the meeting, I’m dressed up and nervous. Typically I have made it beyond the essay-writing stage, the personality test, or the phone interview with HR. This in-person group interview is usually the final step. I sit in the lobby waiting for someone to collect me. An assistant comes around the corner and looks at me, wondering if I could possibly be the next candidate. A little tentative in case a grave mistake has been made, he asks, 'Are you Austin?'

I reply with an enthusiastic yes, pretending I didn’t notice the look of panic that they’d accidentally invited a Black girl to the interview. The tension eases for him as it grips the muscle under my right shoulder blade. I silently take a couple deep breaths as I follow him to the conference room. 'Everyone, this is Austin . . .'

Every pair of eyes looks at me in surprise. They look at the person next to them. They blink. Then they look down at my résumé. Every. Single. Time.

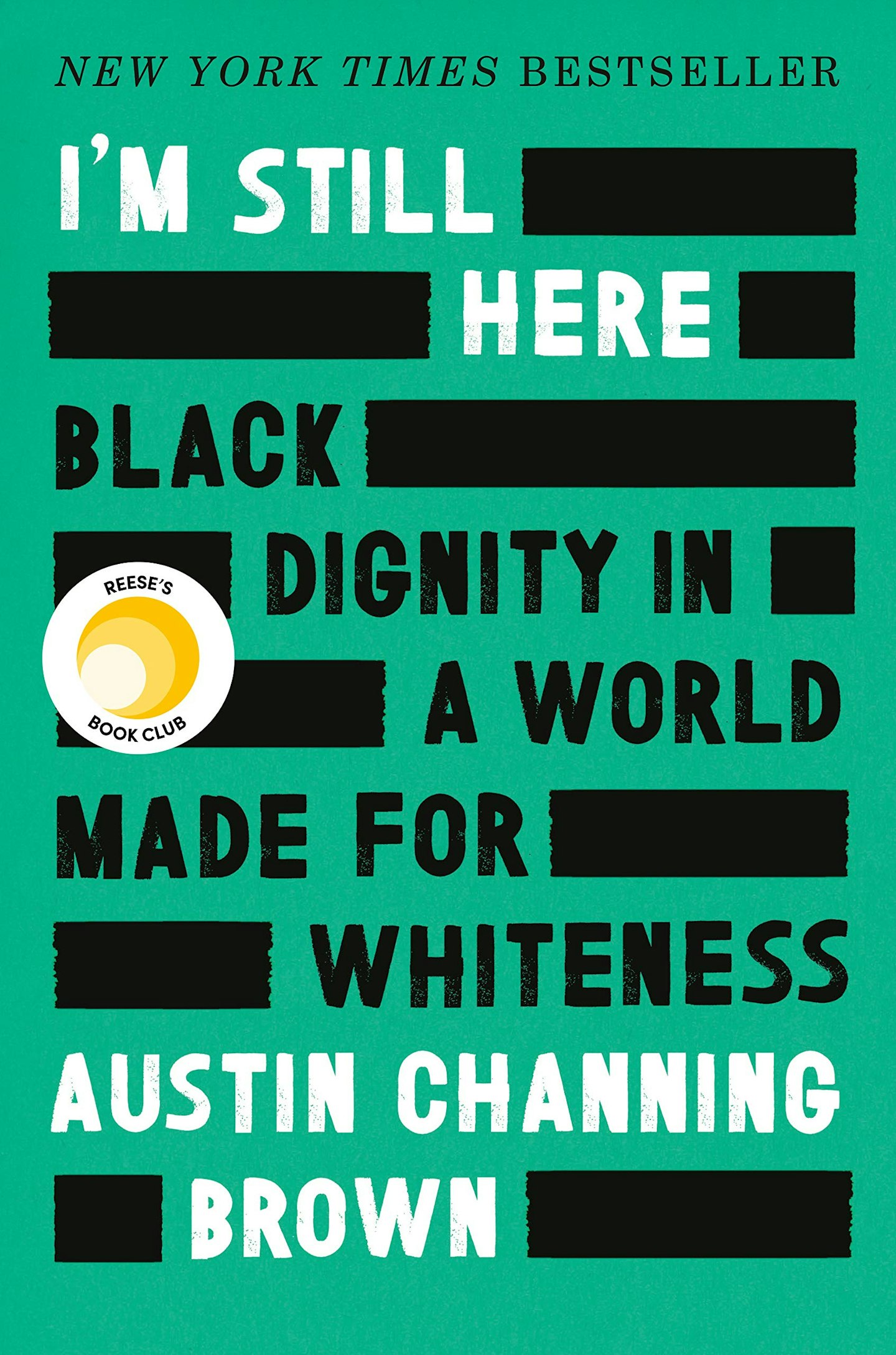

Austin's book, I'm Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness, is out now.