One of the saddest things about the decline of the British high street is our weary acceptance of it. It’s a shame, we think, but what can we do about it? There’s a collective sigh of inevitability, where they should be a gasp of outrage.

As with many of the things we declare to be dead, before they are anything but – print media, record sales, the possibility of an IRL ‘meet cute’ leading to a date – the Internet plays the role of the scythe wielder (although the issues contributing to its decline are multi-faceted and years old). In the world of high street shopping, this week the apparent triumph of digital culture over bricks-and-mortar was made glaringly obvious after ASOS bought Topshop and Miss Selfridge for £330 million. In the terms of the deal, the online giant has not agreed to buy any of the brands’ 70 stores, which employ thousands of people – most of whom are women.

So, Topshop is not dead exactly, but so much about what it stood for– which was always bigger than the clothes – is. Primarily, what we are in danger of losing is an element of community. Shopping on the high street – with pocket money as teens, for ‘going out’ tops in our early twenties – became a shared space of fantasy and escapism. Topshop stood for something democratic: you could enjoy fashion (good fashion in the heyday) without a designer budget. During my adolescence, as is true for so many other millennial women, Topshop played a pivotal role in the development of my then-nascent personal style. It granted me permission to participate.

I’m not deluded enough to think that Sir Philip Green-owned Arcadia was on a philanthropic, feel-good mission in its running of Topshop, but what the brand excelled at was creating physical spaces that were about the experience as much as the transaction (or at least felt like that). Sure, the blow dry bar, café and DJs helped, but the ‘club you’re all welcome in’ atmosphere was primarily achieved by the staff.

I haven’t been the Topshop demographic for years but one Saturday in 2019, I spent an afternoon with a personal shopper in the flagship – or ‘big Topshop’ – store in Oxford Circus for a work assignment. I witnessed a woman, who had worked for the brand for years and had an encyclopedic knowledge of what was on the shop floor, gently encourage a shy teen to try different pieces out. Her growing confidence was palpable. It was uplifting to watch and impossible to recreate online.

If the people made the high street, the people can save it

It’s not a stretch to suggest that there is a whiff of sexism to the resignation with which we accept the dire condition in which the high street finds itself. A 2019 report by the Royal Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, revealed that of the 108,000 jobs lost in sales and customer service roles between 2011 and 2018, 75,000 of them had been occupied by women. There are parallels with how the beauty industry has been treated as a frippery during the Coronavirus crisis.

To look at the stats, to read the headlines, it’s depressing days for the high street. There’s no arguing with that – and isn’t it time we got angry about it? If everything shifts online, we run the risk of losing the human touch that made it shopping it so irresistible in the first place. And if the people made the high street, the people can save it. When the shops reopen, I hope I’ll see you there.

SHOP: The Kate Moss For Topshop Pieces You Can Still Buy In 2021

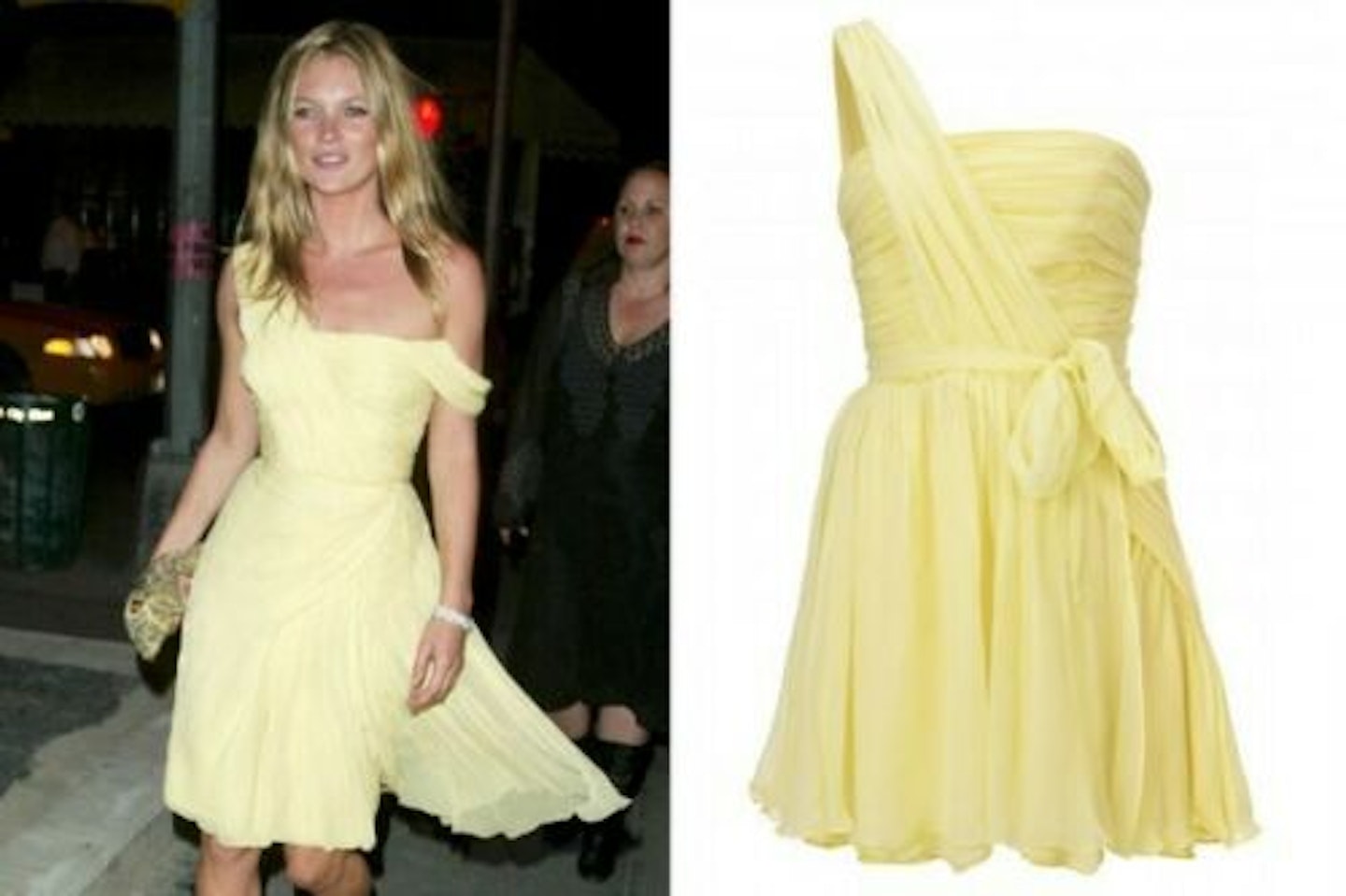

1 of 10

1 of 10Lemon Yellow Prom Dress, From £9

2 of 10

2 of 10Embellished Peplum Dress, From £4.30 at eBay

3 of 10

3 of 10Black Plunge Dress, From £8

4 of 10

4 of 10Black Tassel Dress, £350

5 of 10

5 of 10Yellow Silk Maxi Dress, £299.99

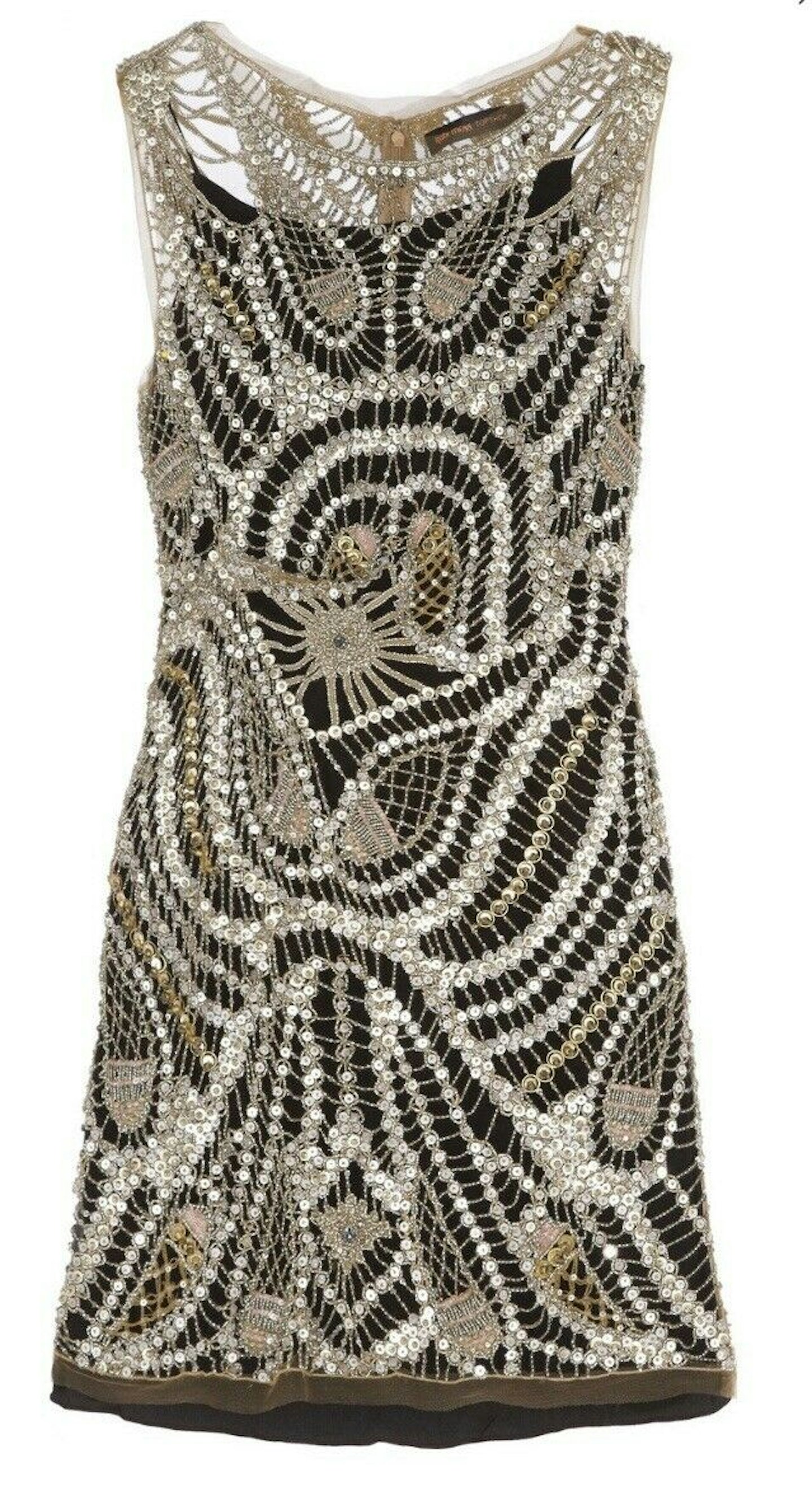

6 of 10

6 of 10Cobweb Beaded Dress, £500

7 of 10

7 of 10Red Ball Gown, £279.99

8 of 10

8 of 10Beaded Maxi Dress, £199.99

9 of 10

9 of 10Pansy Print Dress, £179.99

10 of 10

10 of 10