‘I never went into this industry to be mediocre – that would just be depressing. I went into this industry to be the best,’ says Jonathan Anderson. He admits it’s not very ‘British’ to say this and acknowledges it could be perceived as arrogant, but this is his focus and ultimately what drives him. ‘It’s like running a marathon; you don’t enter the race if you don’t want to come first. I do see fashion like that; it is about winning. I know it sounds kind of ridiculous, but if you want to do good collections and you want to make a successful business, then you have to be out to win.'

I first met Jonathan at the beginning of his race, when he worked out of a windowless studio on Shacklewell Lane in Dalston, East London, and lived close by in a flat above a computer-game shop, furnished with chairs he’d picked out of a skip. Back then, he had a team of four, fitted his designs on a boy, and his debut A/W ’11 womenswear collection, with its hairy hiking boots and silk paisley kilts over matching trousers (inspired by Granny Anderson’s penchant for wearing aprons over trackie bottoms), had been received with rave reviews. We went for lunch and he told me that he worked 24/7 – including Christmas Day.

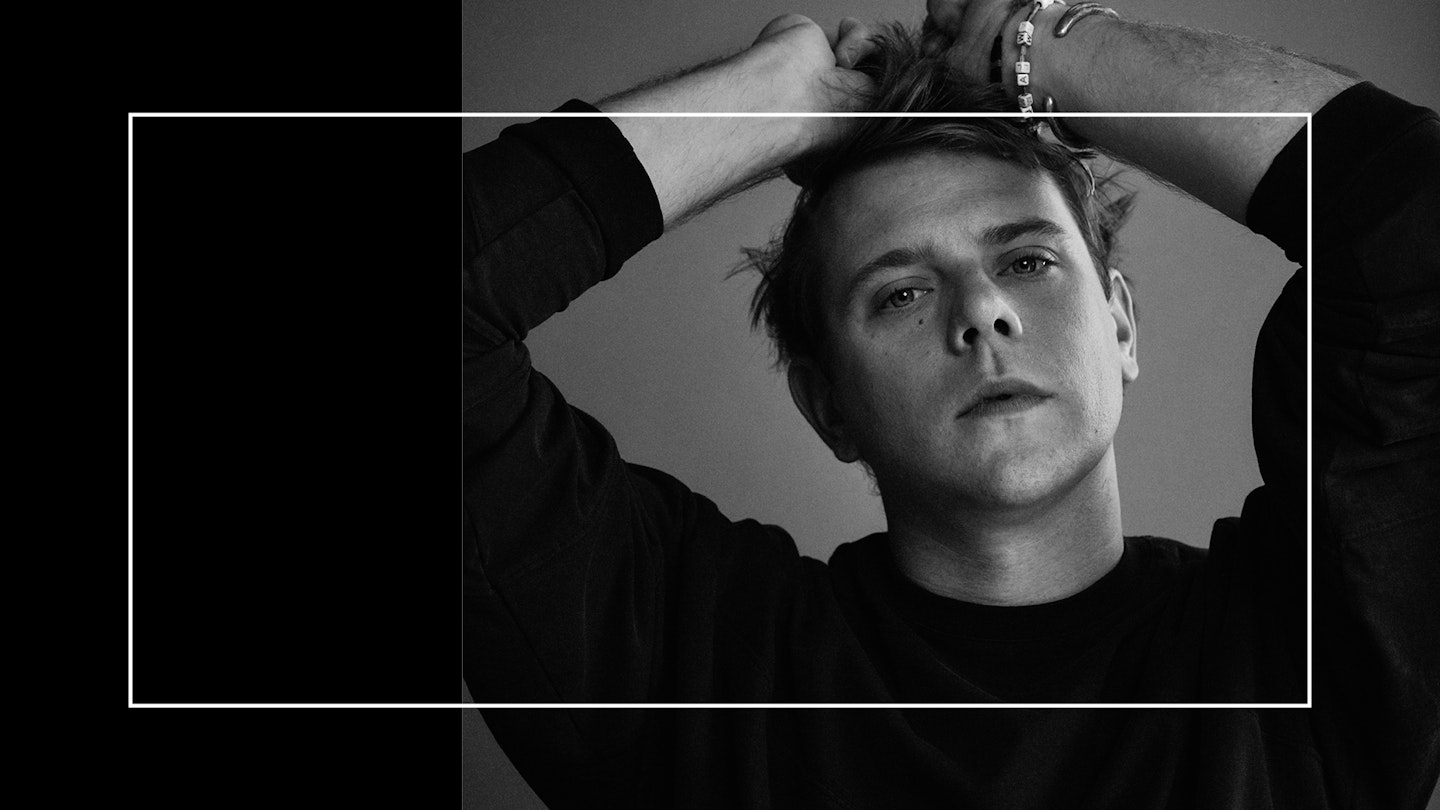

Then in his twenties, he was all lanky limbs with floppy sandy hair and a milky County Derry complexion. Initially, he’d set out wanting to become an actor and trained at the Studio Theatre in Washington DC, but decided acting wasn’t for him and had moved back to Dublin, picking up work in the department store Brown Thomas. A chance encounter there, over the Prada display rack, with the late Manuela Pavesi (Miuccia Prada’s then right-hand woman) inspired him to enrol at the London College of Fashion, where he studied menswear, graduating in 2005 before returning to work with Pavesi as a visual merchandiser for Prada. He launched his career with JW Anderson menswear in 2008 and, two years later, due to popular demand, added womenswear.

Four years after our first encounter, in 2016, I interviewed him again. By this point, industry darling, trend provoker and fashion agitator, he was working out of his new East End headquarters, all concrete floors, white-washed walls and interesting sculptures. He’d clocked up an impressive array of accolades: winning both British men’s and womenswear designer of the year at the Fashion Awards in 2015, which was unheard of, as well as nailing commercial collaborations with Topshop (which sold out) and Uniqlo (which is ongoing, as is Converse).

At just 29, the same year he collaborated with Donatella Versace on her Versus line, he won the backing of Bernard Arnault, chairman of LVMH, the luxury goods conglomerate, and richest man in Europe, who bought a minority stake in JW Anderson. In fact, Arnault had such faith in Jonathan, he also handed him the LVMH- owned Loewe brand, Spain’s answer to Hermès, to creatively direct. Aside from the pressure of overseeing two brands – which he seemed to relish – it was clear that what set him apart from his contemporaries wasn’t just his ability to anticipate the moment in clothes, but that he was equally conversant in commercial.

As he said then, ‘You can’t be a fantasist. It’s impossible. This is a rag trade, you’ve gotta sell it. Quicker. Fast. Faster than ever. It would be awful to produce product that nobody wanted.’ Clearly, that hasn’t been a problem. Those of us who have invested in a JW Anderson bag (bolt pierced, anchor logoed the Keyts, or the Cap) or a Loewe one (Puzzle, Hammock, Gate, Bow, Flamenco, Amazona, Barcelona, Elephant, Basket, to name just the most memorable) can appreciate his prodigious talent for multiple bag hits – the holy grail of any luxury goods brand. As for the clothes, they often hit the spot where the retired Phoebe Philo (of old Céline) left off – judging merely by the volume of JW Anderson and Loewe worn at the shows by both flamboyant street-style professionals and low-key journalists.

‘Recently, I heard someone say I’m less hot-headed,’ muses Jonathan, now 34, whose reputation for having a fiery temper precedes him. So, is he? ‘I think so, yes. When I first took on Loewe and had my own brand, there was an anxiety, because you’re trying to prove [yourself ] all the time and that comes with making harsh decisions. A lot of people don’t like that, they’re petrified of people who think on the spot or have a certain viewpoint. For me, I have a corridor that I work within, very accurately. I am very black or white.’

Today, once again, we are meeting in his new East End headquarters – significantly larger than the last – where he has been installed since February. It is now July, and his studio is still in a state of moving-in with his art and objects yet to be unpacked. You can see why: he lives in London and Paris (where the Loewe design studio is based) and shuttles between both cities every week, plus Madrid (for Loewe’s bag development and manufacturing) every month. ‘I need a five-day week and I need it to be full. The minute I have a gap in the day, I can lose the momentum and then I’m done. And I need to go quick. I can’t do a long meeting. I need people to come prepared, and if they’re not prepared then I won’t do it.

This must be music to the ears of his CEO, Jenny Galimberti, who started with JW Anderson last September. I ask her what impresses her most about Jonathan: ‘He’s fantastic to work with; a constant source of ideas. Intellectually challenging, multifaceted, and with a huge range of conversation topics, from his passion for ceramics to running our business, from politics and macro-economics to really just about anything... We never get bored.’

'I need that level of heightened-ness to make me feel like I have to continue to prove.’

How does Jonathan himself approach being one of the few designers in the industry straddling two businesses – a luxury giant with 113 stores and his own brand, which will open its first flagship in London’s Soho early next year. He says he sees Loewe as a ‘cultural brand’ and JW as a ‘cultural agitator’; he pictures his Loewe woman in a lifestyle space and his JW woman as someone who ‘wants us to push the needle’. . With 18 collections a year to come up with – 10 for Loewe and eight for JW – work is a military operation. He splits the year into four, working on two different ‘chapters’ every quarter, ‘very methodically, always nine months in advance, because I like to work layers and layers and layers into it. I don’t work last minute, it can’t be a stress, it has to be very plotted out.

He still thrives on the pressure, both critical and commercial: ‘There is definitely more pressure on designers who are now judged on their sales performance as well as their creativity. For me, it’s like adrenaline, I need that level of heightened-ness to make me feel like I have to continue to prove.’ Yet despite being in it to win it, he refuses to allow himself to think he’s winning: ‘I never feel that it’s there – if it was, I don’t know if I’d do it any more. I have to continually feel like the underdog.’ As for what he believes it takes to be a successful designer today: ‘You can’t club five days a week, you can’t drink copious amounts of alcohol, you can’t do drugs because you have to have the head space; this is what the job has become, incredibly professionalised. You have to be disciplined, like an athlete, you know?

While he wears the typical nondescript uniform of a celebrated designer – sweatshirt, crumpled linen trousers and duffed-up Loewe trainers – his staff are scurrying about in their gym kits because today is the annual JW Anderson sports day. They all look pretty anxious about the prospect of doing the egg and spoon race in the pouring rain. But sport is close to Jonathan’s heart. His father, Willie Anderson, who he describes as both ‘incredibly supportive and incredibly outspoken’, is the 27-capped Irish rugby international star and rugby union coach.

‘My father grew up on a farm and decided he was going to captain the Irish rugby team, having never played rugby – and he did it. Then he became a coach, which in a weird way is exactly the same as a fashion designer, in that you get hired and fired. As a teenager, I saw my father being fired in spectacular fashion, but he would be like, “Just because I got fired, I will not stop. I will go on to a better team.” You realise how success-driven that is, you kind of get hardened to it and that’s what sticks with me; that drive.’ It was both growing up with a father determined to prove himself on the world stage and living through the troubles in ’90s Northern Ireland that Jonathan believes helped shape his outlook and backbone. ‘I would not be where I am if I didn’t grow up there. I had the most fantastic childhood because I realised it could all be taken away tomorrow. I have gone past a street that has been blown up, I’ve seen someone lying in a car, dead.’ He says he’ll never forget the day his mother, an English teacher, was shopping in Omagh, narrowly missing the bomb that went off.

I ask him how he thinks the current political turmoil – Brexit and Boris – is shaping fashion today? He feels the country’s patriotism has led to a flatness in British culture and a lack of experimentation in fashion. ‘Usually, in political moments like this, creativity should explode or go against the grain. But fashion has contracted in on itself. It’s interesting and weird that such a liberal industry has become so conservative. No one wants to be outspoken, people have become afraid of their peers, the media, the “like” culture of social media – there’s this idea of recreational outrage, like it’s more exciting to destroy something than support it. Instead of being optimistic and supportive of one another, Britain’s become incredibly divisive; it’s not about morals any more, it’s whether you’re in or out.'

He voted to remain, but since the population voted out, he refuses to become ‘fashionably outraged’ and prefers to think instead, ‘How can we resolve this?’ He believes politics and fashion to be in a moment of ‘generational handover’. ‘You have young people all over the world, in America, in Paris where I also live, in Hong Kong, saying, “Look, the decisions that are being made now, we’re going to be stuck with them when we’re older and we don’t want it.” It’s like thunderclouds where hot and cold meet, there’s going to be friction.'

He once told me that his biggest fear in life was to not be relevant any more. ‘Unless you’re Karl Lagerfeld – he’s the only person I look at and think how? To be able to appeal to all demographics, to be able to reinvent yourself, do I have that?’ he asked at the time. Today, he says Lagerfeld’s passing marks a pivotal point. ‘Ultimately, he was the end of that period. He was at the pinnacle, he held the fort, he was the figurehead of fashion. Now that he is no longer there, I feel we’re in this moment of freefall, not just because of him, but what the industry stood for. I have huge respect for Karl.’

He also admires Miuccia Prada, who ‘brought a new voice to fashion’ and admits he has been fascinated by the ‘enigmatic’ Hedi Slimane since his college days. To my surprise, he also declares his respect for the designer Jeremy Scott – ‘all that optimism, he has not changed who he is and I like that. He really knows how to talk to people, his humour, he’s not elite.’

JW Anderson Collection

1 of 17

1 of 17JW Anderson

2 of 17

2 of 17JW Anderson

3 of 17

3 of 17JW Anderson

4 of 17

4 of 17JW Anderson

5 of 17

5 of 17JW Anderson

6 of 17

6 of 17JW Anderson

7 of 17

7 of 17JW Anderson

8 of 17

8 of 17JW Anderson

9 of 17

9 of 17JW Anderson

10 of 17

10 of 17JW Anderson

11 of 17

11 of 17JW Anderson

12 of 17

12 of 17JW Anderson

13 of 17

13 of 17JW Anderson

14 of 17

14 of 17JW Anderson

15 of 17

15 of 17JW Anderson

16 of 17

16 of 17JW Anderson

17 of 17

17 of 17JW Anderson

Jonathan’s own fashion ascent, since he vaulted into the industry’s big league with lightning rod shows that flash up the new season’s trends and clothes that have become ever more elegant, glamorous and grown-up, is quite remarkable. He has been very successful very young, and in a relatively short time. Perhaps that is why there is so much jealousy at the mention of his name. Some accuse him of being handed his career on a silver platter, thanks to the financial and mentoring support of luxury giant LVMH – but that’s surely a position he wouldn’t find himself in had he not the discipline or vision to pull it off.

Others accuse him of being ‘a puzzle of others’, comparing him to a cover artist, taking ideas and remaking them in his own image, like a Lady Gaga (after Madonna) or a Grace Jones (after Edith Piaf ) – a criticism that, frankly, could be levelled at almost any designer today, for what is truly ‘new’ in fashion? Naturally, those who buy his designs and sell them like hot cakes have nothing but positives to say. ‘He’s managed to create his own code, which he translates across so many collections and collaborations, from Converse and Uniqlo to Loewe. It’s aspirational and desirable without being uptight; he’s created a kind of modern uniform,’ says Harvey Nichols’ head of fashion Laura Larbalestier. Holli Rogers, chief fashion officer at Farfetch, agrees: ‘We always want designers to be consistent and clear. However, there needs to be an element of continuous development, which is hard to do without rewriting the book and moving away from your aesthetic. But Jonathan does exactly this by continuing to innovate and distil his brand identity without losing integrity.

'Fashion now is about being able to sell dreams, because if you can’t escape, then what is the point?'

He’s a beacon of British fashion, who manages to run two very different brands in ways that don’t cannibalise each other, but rather remain complementary.’ High praise, too, comes from Natalie Kingham, fashion buyer of luxury etailer Matches Fashion, who simply adds, ‘I don’t really feel he has any direct competition, as what he’s doing is original. And I think he has longevity. Being a designer is in his blood – he loves architecture, music, art and he embodies all these elements and brings them into his work in a way that is unique.

When i ask Jonathan about having a certain reputation – personally, I find his blunt outspokenness a joy in the helium- inflated fashion bubble, but I wonder how some mean-spiritedness from other corners affects him – he says, sure, some people find him difficult. ‘I’m not going to be told what to do. I will listen, but if I don’t agree with it,Iwon’tdoit.Attheendoftheday,Ihave two businesses to protect, and the people who work there, they’re my priority; I choose to work with some incredibly difficult characters – why? Because I need that kind of debate, I hate “yes” people, I need that conflict.'

So, where is he now in his marathon race? Fashion, by its very nature, makes a designer hot one moment and not the next, so how does he intend to avoid becoming a casualty of his own success? By being continually curious, constantly reinventing himself and, hopefully, he says, knowing when it’s time to step away. That, thankfully, doesn’t sound like it will be any time soon: ‘I love the work, the idea of being driven, creating something that is going to make you escape. Fashion now is about being able to sell dreams, because if you can’t escape, then what is the point?